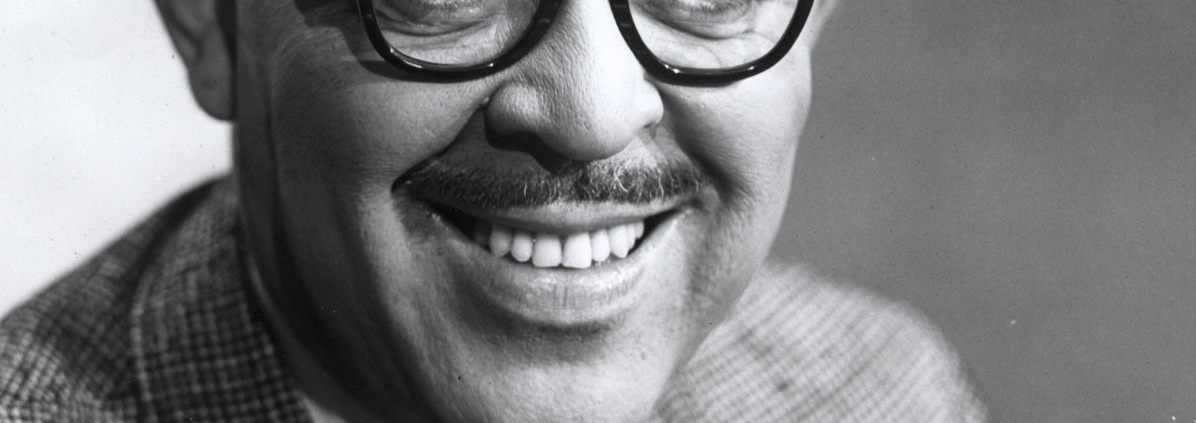

Wendell Smith

Wendell Smith built a media career that would eventually be recognized in the National Baseball Hall of Fame. He’s best known for his campaign to integrate major league baseball, which resulted in Jackie Robinson’s debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. Wendell Smith, however, was more than an activist. During his 35-year career, he evolved into a well-rounded journalist with solid skills as an interviewer and a writer. In addition, he exhibited a friendly and modest persona. Smith’s qualities gained the respect and admiration of many of his peers, while helping him succeed at the Pittsburgh Courier and emerge as a racial pioneer in mainstream journalism. Among other achievements, Smith became one of the first black sportswriters to work for a daily newspaper. Since his death in 1972, he has received many posthumous honors, including the J.G. Taylor Spink Award given by the Baseball Writers Association of America (BBWAA). The Spink awards are displayed in the Scribes & Mikemen exhibit area of the Hall of Fame’s Giamatti Library.

Wendell Smith built a media career that would eventually be recognized in the National Baseball Hall of Fame. He’s best known for his campaign to integrate major league baseball, which resulted in Jackie Robinson’s debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. Wendell Smith, however, was more than an activist. During his 35-year career, he evolved into a well-rounded journalist with solid skills as an interviewer and a writer. In addition, he exhibited a friendly and modest persona. Smith’s qualities gained the respect and admiration of many of his peers, while helping him succeed at the Pittsburgh Courier and emerge as a racial pioneer in mainstream journalism. Among other achievements, Smith became one of the first black sportswriters to work for a daily newspaper. Since his death in 1972, he has received many posthumous honors, including the J.G. Taylor Spink Award given by the Baseball Writers Association of America (BBWAA). The Spink awards are displayed in the Scribes & Mikemen exhibit area of the Hall of Fame’s Giamatti Library.

John Wendell Smith, an only child, was born in Detroit, Michigan on June 27, 1914.1 His father, John Henry Smith, grew up in Dresden, Ontario, Canada.2 John Henry Smith cooked for Canadian and American railroads and Great Lakes ships. He migrated to Detroit in 1911. The elder Smith later served as head steward at the city’s Yondotega Club, an exclusive social organization. He also worked as a private chef for Henry Ford, the founder of the Ford Motor Company.3 In 1912, he married Detroit native Lena Gertrude Thompson. She was a housewife and a member of three volunteer groups connected with St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church (now St. Matthew’s and St. Joseph’s Episcopal Church)–Willing Workers, King’s Daughters, and the Dorcas Society.4

Smith grew up in a predominantly white, working class neighborhood on Detroit’s east side. He pitched during sandlot baseball games with youths on his block, including Mike Tresh.5 Tresh later spent 12 seasons in the major leagues, playing for the Chicago White Sox and Cleveland Indians. Tresh’s son, Tom, also played in the major leagues.

According to Smith’s friend and former neighbor, Martin Hogan, Smith first saw Negro League baseball in the Motor City.6 The Detroit Stars, led by outfielder Turkey Stearnes, played at Mack Park, a single-decked, wooden stadium located near Smith’s home.7 Smith and Hogan walked to the stadium without money. Often the gatekeepers let them in after a few innings, or another visitor brought them inside the park.

Smith also played basketball for the Detroit Athletic Association team at the Central Community Center.8 Sportswriter Russell J. Cowans wrote about one of Smith’s basketball games in 1932.

“With Wendell Smith, 17-year-old Eastern high school forward pacing the way with seven baskets and three fouls shots, the Detroit Athletic Association basketball team crushed the highly-touted Cincinnati Lion Tamers Saturday night 62 to 22, at the Central Community center gymnasium.

“Smith was a thorn in the sides of the Cincinnati outfit. He was all over the court raimming [sic] the hoop with most of his shots. He might have increased his total but numerous times he passed to a teammate with an easy shot near the basket.”9

Despite these good times, Smith experienced some racial problems. According to Hogan, he was not allowed to play on sports teams at predominantly white Southeastern High School. “I know it was hard for him,” Hogan said. “He was not permitted to play sports. I don’t know whose policy it was.”10

Smith played American Legion baseball, but officials removed him from the team. Henry Ford interceded on Smith’s behalf and he was reinstated. 11

Smith suffered a crushing blow as a teenager. During an interview with Jerome Holtzman, he said he had won an American Legion baseball championship game, but after the game Detroit scout Wish Egan told Smith he could not sign him because he was black. Egan signed the losing pitcher and Mike Tresh, Smith’s teammate.12 According to Smith’s widow, Wyonella, Smith cried.13 The incident spurred Smith’s activism.

After high school, Smith enrolled in West Virginia State College (now West Virginia State University) in 1933 as a physical education major. The school, located in Institute, West Virginia, was predominantly black. He met his first wife, the former Sara Wright, at the school. Wright minored in music. They married during the late 1930s.14

Smith competed for the school’s baseball and basketball teams. On Christmas Day, 1933, the Yellow Jackets basketball team faced Smith’s old squad, which had changed its name from Detroit Athletic Association to the Central Big Five, in Detroit. Smith scored nine points, but West Virginia State lost. 28-19.15

Smith began to develop his media skills in college. As the football team’s publicist, he kept sportswriters informed about the squad’s progress. He wrote a sports column for the campus newspaper, the Yellow Jacket. In one column, he praised Pittsburgh Courier columnist Ches Washington for his coverage of the school’s football team.16

After Smith graduated in 1937, he got a job with the Courier. At the time, the weekly was one of the leading black newspapers in the United States. Smith started with a salary of $17 per week. While at the Courier, he extensively covered Negro League baseball, helping to preserve the exploits of the players and owners for future scholars and fans.

In 1938, Smith launched his fight against baseball’s color line with his column “A Strange Tribe,” which criticized blacks for supporting major league baseball when it maintained a color line.

“They’re real troopers, these guys who risk their money and devote their lives to Negro baseball. We black folk offer no encouragement and don’t seem to care if they make a go of it or not. We literally ignore them completely. With our noses high and our hands deep in our pockets, squeezing the same dollar that we hand out to the white players, we walk past their ball parks and go to the major league game. Nuts — that’s what we are. Just plain nuts!”17

The following year, Smith made strides at the paper. He surveyed major league players about their attitudes toward black players. He wanted to disprove the idea that the players opposed blacks in the majors. He talked to 40 players and eight managers at the Schenley Hotel, located near the Pittsburgh Pirates’ Forbes Field. Most of the interviewees said they did not oppose integration. Smith later told Holtzman the Courier management liked the survey and gave him a raise.18

In 1940, Smith got good news at home and work. Sara Smith gave birth to their son, John Wendell Smith Jr. The boy would be Smith’s only child. That same year, the paper promoted him to city editor; he eventually advanced to sports editor.

Smith, along with other black sportswriters, campaigned for the integration of major league baseball during the 1940s. The list of activists includes Joe Bostic, of the Harlem-based People’s Voice, and Sam Lacy, of the Washington D.C.-based Afro-American.

Lacy described his and Smith’s mutual passion for the fight. He wrote: “We talked deep into the nights in ghetto hotels, at his house in Pittsburgh and in my home in Washington, at dimly-lit ballparks where our paths would cross while covering Negro National League games, in lunchrooms in Harlem and in greasy spoon hogmaw joints of Memphis, St. Louis, Baltimore and Philadelphia.”19

Bostic took two Negro League players to the Brooklyn Dodgers’ camp unannounced to demand a tryout in early April 1945. Later that month, Smith had taken three Negro League players to a prearranged tryout with the Boston Red Sox. The players were Robinson, a shortstop for the Kansas City Monarchs, Marvin Williams, a second baseman for the Philadelphia Stars, and Sam Jethroe, a center fielder for the Cleveland Buckeyes.20 That tryout generated little publicity in the mainstream media.

On the way home afterward, Smith met Dodgers president Branch Rickey in New York. Rickey asked Smith if any of the players he took to Boston could succeed in the majors. Smith recommended Robinson.

Smith later told sportswriter Shirley Povich why he had touted Robinson. “He wasn’t the best Negro ballplayer I could have named. There were others with more ability but to have recommended them would have been a disservice to the cause of the Negroes.

“I recommended Robinson because he wouldn’t make Negro baseball look bad either on the field or off it. Jackie got my vote because of many factors. He was a college boy. I knew he would understand the great responsibilities of being the first Negro invited to play in organized baseball in more than 60 years. He was a mannerly fellow. At UCLA he had played before big crowds. I gambled that he wouldn’t freeze up under pressure. And he had an honorable discharge from the Army as a lieutenant.”21

The recommendation helped both Robinson and Smith. In August 1945, Rickey met with Robinson in Brooklyn. Two months later, Rickey signed him to a minor league contract. To assist Robinson, Rickey paid Smith to serve as Robinson’s mentor and arrange for lodging and travel during 1946 and 1947. During the 1946 season, Robinson played for the Montreal Royals, the Dodgers’ Triple-A affiliate. Robinson led the Royals to the championship of the International League and victory in the Little World Series. Smith wrote stories about his progress.

The following year, Smith watched history unfold. On April 15, 1947, he sat along with other sportswriters in the press box at the Brooklyn Dodgers’ Ebbets Field. The Dodgers played their season opener against the Boston Braves. Smith took notes while Robinson took the field as the first black man to play major league baseball in the modern era. The Dodgers won the game 5-3. Robinson didn’t record a hit, but he scored one run and played first base flawlessly.

Smith produced four stories. In one, he wrote: “It was a great day. It was a great day for Brooklyn. It was a great day for baseball, and above all, a great day for JACKIE ROBINSON!”22

After Robinson joined the Dodgers, Smith ghosted a Courier column for him.

In August 1947, Smith joined the Chicago Herald-American, an afternoon newspaper. He became one of the first black sportswriters to work for a daily newspaper.23 Smith initially split time between the Courier and the Herald-American before he eventually left the Pittsburgh paper. Smith’s first assignment for the Herald-American was a series of articles about Robinson’s rise to the major leagues. He contended that Robinson’s signing proved anyone could succeed in this country. “It’s a story of this great country and proves beyond every doubt that a man can soar to lofty heights in the United States if he has the ability,” he wrote. “True enough, the struggle may be more difficult for some more than others, but Jackie Robinson, a Negro and first baseman for the Brooklyn Dodgers, is proof enough that it can happen.24

Smith notched a few achievements in 1948. He wrote the first biography of Robinson, entitled Jackie Robinson: My Own Story. The book has one embarrassing error: it lists Robinson’s full name as “John Roosevelt Robinson.” The correct name is Jack Roosevelt Robinson.25 That same year, Smith became one of the first black writers admitted into the BBWAA and covered the Summer Olympics in London for the Courier.

Smith’s personal life changed during this period. He and Sara Smith divorced. Sara eventually remarried and obtained a Broadcast Music, Inc., composer’s license. She handled about 30 recording acts.26 John Wendell Smith Jr. followed his mother into the music business. He released a few songs, including a high-tempo rocker called “Puddin’ Pie.”27 Sara Smith helped manage her son’s music career.28

Wendell Smith married the former Wyonella Hicks in 1949. They had met while they worked at the Courier. After they moved to Chicago, Wyonella Smith worked as a secretary for Harlem Globetrotters owner Abe Saperstein.29

In 1949, Smith’s previously warm relationship with Robinson began to change. Smith slammed Robinson in the Courier for hinting that some sports reporters were treating him unfairly after a confrontation between Robinson and a teammate. Smith alleged Robinson “isn’t as popular in the press box as he once was.”30 According to a Chicago Tribune article written by Holtzman in 1993, Smith had told him he and Robinson had fallen out and hadn’t spoken in nearly ten years. In the same article, Holtzman reported Wyonella Smith’s insistence that the two men had remained friends.31

In addition to his work covering baseball, Smith became a noted boxing writer. During the 1950s, Smith notched achievements in the field. He was elected president of the Chicago Boxing Writers and Broadcasters Association in 1953. Smith established another first for black sports journalists in 1958. That March, he provided radio commentary, along with Dr. Joyce Brothers and Jack Drees, for the middleweight championship fight between Sugar Ray Robinson and Carmen Basilio at Chicago Stadium.

Smith conducted his final media crusade in 1961. At the time, black major leaguers whose teams held spring training in the southern states still had to stay in segregated accommodations. The lodgings and dining available to them were less desirable than those their white teammates enjoyed. Smith covered the issue in both the Chicago’s American, which had evolved from the Herald-American, and the Courier.

In the January 23, 1961, issue of the American, Smith wrote: “Beneath the apparently tranquil surface of baseball there is a growing feeling of resentment among Negro major leaguers who still experience embarrassment, humiliation, and even indignities during spring training in the south. This stature of respectability the Negro has attained since [Jackie] Robinson’s spectacular appearance on the major league scene has given him a new sense of dignity and pride, and he wants the same treatment in the south during spring training that he has earned in the north.”

“The Negro player resents the fact that he is not permitted to stay in the same hotels with his teammates during spring training, and is protesting the fact that they cannot eat in the same restaurants, nor enjoy other privileges.”32

During the campaign, Smith deployed blunt prose. After Birdie Tebbetts, then vice president of the Milwaukee Braves, claimed the black members of the Braves were satisfied with segregated accommodations, an angry Smith wrote the following for the Courier:

“When Mr. Birdie Tebbets [sic] was a major league catcher, he was acknowledged as a competent receiver but never considered dangerous at the plate in a crucial situation.

“On the basis of his reception to the nationwide protests over the deplorable conditions which Negro players — particularly his own — must tolerate in the South during spring training season, one can only conclude that Mr. Tebbets [sic] is still a weakling when the chips are down.”33

Full integration throughout spring training accommodations in Florida and Arizona took place within the next two years.34

Smith earned recognition for the desegregation campaign. The magazine Editor & Publisher called him a reporter with “a built-in social conscience.”35 In October 1961, Smith received a second prize among Chicago sports reporters from the Associated Press.36

Two years later, Smith left the American. He became one of the first black journalists to work for a Chicago television station when he joined WBBM to cover news and sports in February 1963.37 A year later, he switched to WGN, another Chicago television station. At WGN, Smith joined a sports team led by Jack Brickhouse.38 At the time, Brickhouse was building a career as the longtime announcer of Chicago Cubs games at the station. Smith eventually became the sports anchor for the station’s 10 P.M. news broadcast. Smith also helped the news division by covering stories and working on special projects. In 1965, the station broadcast a show about the first ten years of Richard J. Daley’s career as mayor of Chicago. As part of the program, Smith interviewed Daley and accompanied the mayor on a helicopter tour of the city. That same year, Smith produced a show about the social gains made by blacks in Chicago. Smith also frequently appeared on People to People, an urban affairs television program broadcast on WGN.

Smith made additional career advances during his later years. He started writing a weekly sports column for the Chicago Sun-Times in 1969. In 1971, he was named to the Special Committee on the Negro Leagues for the Baseball Hall of Fame. That committee made Satchel Paige its first choice for induction in the Hall of Fame. In January 1972, he won election as the first black president of the Chicago Press Club.

By 1972, the relationship between Smith and Robinson had warmed. Robinson released his final autobiography, I Never Had It Made: An Autobiography of Jackie Robinson. In the book, he acknowledged his debt to Smith for his recommendation to Rickey.39 During that year, Robinson and Smith appeared together in Chicago and recounted Robinson’s tryout with the Red Sox.40

After Robinson passed away that October, Smith memorialized him in a column for the Sun-Times.41 Sometime later, Smith, suffering from cancer, was hospitalized. Robinson’s co-author, Al Duckett, visited him. Smith told Duckett he was thrilled about Robinson’s acknowledgement.42 Shortly afterward, on November 26, 1972, Smith passed away.

For about three weeks after Smith died, tributes flowed in from Chicago and national journalists.

“He was an able newsman, but more, a respected gentleman in his profession and a dear friend,” Irv Kupcinet wrote for the Sun-Times.43

“There was a soft humor about Wendell, never anything vicious,” Jack Griffin wrote for the Sun-Times. “He was a fairly big man. He walked with a sort of a shuffle, a limp left over from his athletic days at West Virginia State.

“I knew the part he had played in bringing Jackie Robinson in the major leagues as baseball’s first black player. I knew because other people told me. Wendell never mentioned it. He never operated with the bugles playing.”44

“Wendell was neither a black bigot nor an Uncle Tom,” Robert Cromie wrote for the Chicago Tribune. He was a beautiful guy who liked all good people and was, in turn, liked by everyone worth bothering about. He could lose his temper. I once saw him shove a burly guard aside in Yankee Stadium after an altercation — with an ease that made me suddenly realize how very strong he was. But laughter was more his style. I always think of him as laughing because he had so delightful a sense of humor”45

“Like old soldiers, sportswriters never die, they just fade away, and black baseball players of the Negro Leagues, as well as black major leaguers of the present and the past, should never let his memory die,” Brad Pye, Jr. wrote for the Los Angeles Sentinel.46

The memory of Smith has not died. Within a month after his death, the Chicago Press Club renamed its scholarship fund the Wendell Smith-Chicago Press Club Scholarship Fund. Around the same time, the Chicago Sun-Times donated $1,000 for a scholarship in Smith’s memory to be awarded through the National Merit Scholarship Fund.

In 1973, the Chicago Board of Education named an elementary school in his honor. The Chicago Baseball Writers group created the Wendell Smith Award. The University of Notre Dame and DePaul University established a Wendell Smith Award, given to the Most Valuable Player of the schools’ annual basketball game in 1973.47 In 1975, the Chicago Park District named a park after Smith. In 1982, Smith was elected to the Chicago Journalism Hall of Fame; he was elected to the Chicagoland Sports Hall of Fame in 1983.48

After Smith’s death, Wyonella Smith worked in the public information office for the City of Chicago’s Department of Aging.49 She eventually moved into a senior residence facility located on the city’s South Side. The same facility housed Mary Frances Veeck, the widow of former White Sox owner Bill Veeck. The two women have maintained a strong friendship.50

Public interest in Wendell Smith increased during the 1990s. The BBWAA’s Spink Award committee nominated Smith in 1993. The full membership voted for it, making him the first African-American to receive the honor. In 1994, Wyonella Smith accepted the award on his behalf at the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s annual summer ceremonies. West Virginia State University inducted him into its hall of fame the same year. The following year, Holtzman released an updated edition of his book, No Cheering in the Press Box. The book, a collection of interviews with sportswriters, includes his interview with Smith.

In 2013, Smith received more posthumous recognition. The film 42, which took its title from Robinson’s jersey number, was released in theaters. The film focused primarily on Robinson’s first two years with the Dodgers organization and depicted his relationship with Smith. The National Association of Black Journalists inducted Smith into its Hall of Fame.51 The Shirley Povich Center for Sports Journalism at the University of Maryland’s Philip Merrill College of Journalism created the Sam Lacy-Wendell Smith Award. The award recognizes a sports journalist or broadcaster who has made significant contributions to racial and gender equality in sport.52

A year later, in 2014, the Associated Press Sports Editors honored Smith with their Red Smith Award.53

Smith had gained wide admiration and respect, but did not escape criticism. Chicago Defender columnist Fay Young claimed Smith was “anxious to grab off some glory” when he took players to the tryout with the Red Sox.54 Michigan Chronicle sportswriter Bill Matney claimed that Smith recommended a high school player to Rickey without observing the player in person. That player flopped in the minor leagues.55 When a black Brooklyn player opted to stay in a black hotel instead of housing with the rest of the team in a white-owned hotel, Smith wrote an angry letter to the player. The player gave the letter to a team official, who tried to chastise Smith.56

Author Mark Ribowsky criticized Smith in his book, A Complete History of the Negro Leagues, 1884 to 1955. Ribowsky alleged Smith and other writers for the black press helped destroy the Negro Leagues. He argued that writers cut back on coverage of black baseball in favor of the major leagues after Robinson joined the Dodgers.57

Smith’s actions contradict that claim. In May 1947, Smith had reminded readers to continue to support black baseball.58 In a 1949 letter to Rickey, Smith suggested that the Dodgers sponsor a black baseball team.59 Smith continued to cover the Negro Leagues’ East-West All-Star game.60

Despite this scattered criticism, most observers recognize Smith’s professional achievements and modest personality.

A late-career example of this mindset took place in 1960. By then, he had established a strong reputation in his field. Yet, he did not focus on himself. Instead, he expressed gratitude to others for his career. In a column for the Courier, he thanked previous Courier sports editors for blazing a trail for his own career.

“This has been a life of splendor and excitement — baseball training camps, fight camps, the Olympics and other arenas of excitement for the younger ones that the older ones, by their dedication and perseverance made possible.

“Thus those who sit in the press box at the World Series, or ringside at the big fights, or in “typewriter row” at similar classics, should remember that they are there because of the ceaseless campaigns waged by those before them, particularly by those representing this newspaper.”61

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank the Chatham-Kent (Ontario, Canada) Public Library; the Chicago Public Library’s Special Collections and Preservation Division; the Chicago Public Library’s Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection; the Detroit Public Library’s Burton Historical Collection; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Inc.; the West Virginia State University Archives and Special Collections Department; and West Virginia State University’s Sports Information Department.

This biography was reviewed by Jack Zerby and Donna L. Halper and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted the following books, periodicals, and internet websites:

Buni, Andrew. Robert L. Vann of the Pittsburgh Courier: Politics and Black Journalism (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1974).

Cooper, John. Season of Rage: Hugh Burnett and the Struggle for Civil Rights (Toronto: Tundra Books, 2005).

Manley, Effa and Hardwick, Leon Herbert. Negro Baseball … Before Integration (Adams Press. Chicago, 1976).

Peterson, Robert. Only the Ball Was White: A History of Legendary Black Players and All-Black Professional Teams (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970).

Rampersad, Arnold. Jackie Robinson: A Biography (New York: Knopf, 1997).

Reisler, Jim. Black Writers, Black Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1994).

Robinson, Jackie. Baseball Has Done It (Philadelphia: Lippincott: 1964).

Ruck, Rob. Sandlot Seasons: Sport in Black Pittsburgh (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1993).

Rowan, Carl with Jackie Robinson. Wait till next year: the life story of Jackie Robinson (New York: Random House, 1960).

Tygiel, Jules. Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and his legacy. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983).

Wiggins, David K. “Wendell Smith, the Pittsburgh Courier-Journal and the Campaign to Include Blacks in Organized Baseball, 1933-1945,” The Journal of Sports History (1983): 5-29.

Weaver, Bill L. “The Black Press and the Assault on Professional Baseball’s “Color Line,” October, 1945-April, 1947,” Phylon (Fourth Quarter, 1979, Volume XL, No. 4).

Bleske, Glen L. “Agenda for Equality: Heavy Hitting Sportswriter Wendell Smith,” Media History Digest (Fall-Winter, 1993): 38-42.

Ancestry.com, Chicagobaseballmuseum.org, Newspapers.com, PaperofRecord.com, YouTube.com.

Notes

1 The date of birth was stated on the draft card Smith completed during World War II.

2 One of Wendell Smith’s cousins, Hugh Burnett, campaigned against racial discrimination in Dresden, Ontario, during the 1950s. His efforts are noted in John Cooper’s book, Season of Rage: Hugh Burnett and the Struggle for Civil Rights, published in 2005.

3 Michigan Chronicle, July 9, 1966, A-1. The same article names another cousin of Wendell Smith, Herb Jeffries. Jeffries, also known as Herbert Jeffrey, was a singer and an actor who earned some renown as cinema’s first black singing cowboy during the 1930s. He starred in “The Bronze Buckaroo” and other Westerns. Jeffries also sang with Duke Ellington in the 1940s.

4 Detroit Free Press, October 1, 1970: 17-C.

5 Wendell Smith, “Smitty’s Sport Spurts,” Pittsburgh Courier, January 27, 1940: 16.

6 Martin Hogan, telephone interview with the author, June 11, 1996.

7 Richard Bak. Turkey Stearnes and The Detroit Stars: The Negro Leagues in Detroit, 1919-1933 (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1995), 58.

8 The Central Community Center was eventually renamed the Brewster-Wheeler Recreation Center. It was closed in 2006.

9 Russell J. Cowans, “Detroit Nips Cincinnati 5,” Chicago Defender, January 16, 1932: 9.

10 Hogan interview. The yearbook from Smith’s senior year in high school does not list participation in any extracurricular activities for Smith.

11 Editor & Publisher, “Sports Writer Champions Desegregation in Baseball,” April 1, 1960.

12 Jerome Holtzman, No Cheering in the Press Box (New York: Henry Holt, 1995), 323.

13 Dave Hoekstra, “Jackie Robinson and sportswriter Wendell Smith: a team for the ages,” Chicago Sun-Times, April 7, 2013.

14 While Smith attended West Virginia State, he established a long-term friendship with his roommate Will Robinson. Robinson lettered in four sports at West Virginia State University, graduating in 1937. Robinson coached Pershing High School in Detroit, where he won the state title in 1967 with a team led by future National Basketball Association star Spencer Haywood. Robinson later became the first black scout in the National Football League (Lions) and the first black head coach for an NCAA Division I school (Illinois State University). There, he coached future NBA player and head coach Doug Collins.

15 Russell J. Cowans, “Detroit Team Defeats West Virginia 28-19, The Tribune Independent, December 30, 1933: 7

16 Wendell Smith, “Sportiana,” The Yellow Jacket.

17 Wendell Smith, Smitty’s Sport Spurts, Pittsburgh Courier, May 14, 1938: 17.

18 Holtzman, 315.

19 Sam Lacy, “Opening Much More than Pandora’s Box,” The Afro-American, March 13, 1973: 7.

20 Jethroe eventually played in the major leagues. He won Rookie of the Year honors after his debut with the Boston Braves in 1950. He also played for the Pittsburgh Pirates.

21 Shirley Povich, All These Mornings (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1969), 13.

22 Benedict Cosgrove, Covering the Bases: The Most Unforgettable Moments in Baseball in the Words of the Writers and Broadcasters Who Were There (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1997), 74.

23 Smith continued to write a sports column for the Pittsburgh Courier on a freelance basis until 1967.

24 Wendell Smith, “Jackie Robinson’s Story the Saga of a New America,” Chicago Herald-American, August 20, 1940: 25.

25 Jackie Robinson as told to Wendell Smith, Jackie Robinson: My Own Story. (Greenberg: New York, 1948): 7.

26 Chicago Defender, “Son of Sports Scribe Discs ‘Puddin’Pie’,” July 12, 1960: 21.

27 Chicago Defender, “Son of Sports Scribe.” The song “Puddin’ Pie” can be found at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RzLZyaK7Vt8.

28 John Wendell Smith Jr. died in 1988. Sara Smith, later Sara Bembry, died in 1992.

29 “Personalities in the News: TV Newsman produces ‘Negro in Chicago,’” Chicago Defender, March 16, 1965: 11.

30 Wendell Smith, “Wendell Smith’s Sports Beat,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 19, 1949: 10.

31 Jerome Holtzman, “Jackie Robinson and the Great American Pastime: And the man behind him,” Chicago Tribune, April 11, 1993: B-4, 5, 15.

32 Wendell Smith, “Negro Ball Players Want Rights in South,” Chicago’s American, January 23, 1961: 1.

33 Wendell Smith, “Wendell Smith’s Sports Beat,” Pittsburgh Courier, February 18, 1961: 27.

34 Brian Carroll, “Wendell Smith’s Last Crusade: The Desegregation of Spring Training, 1961,” The 13th Annual Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, William Simons, ed., (McFarland Press, Jefferson, North Carolina), 2002.

35 Editor & Publisher, “Sports Writer Champions Desegregation in Baseball,” April 1, 1960.

36 Chicago’s American, “Newswriting Winners Named,” October 15, 1961.

37 Chicago’s American, “Smith to Enter TV, Radio Field,” February 9, 1963.

38 George Castle, “Brickhouse top on-air salesman for both sports, racial tolerance,” Chicago Baseball Museum website. The article includes a recording of part of Smith’s broadcast from June 11, 1967.

39 Jackie Robinson and Al Duckett. I Never Had It Made: An Autobiography of Jackie Robinson. (New York: HarperCollins, 1972), 41.

40 David Condon, “Jackie Robinson: A Man of Summer,” Chicago Tribune, June 25, 1972: S-3, 3.

41 Wendell Smith, “The Jackie Robinson I knew,” Chicago Sun-Times, October 25, 1972: 98, 100.

42 Jet, “Sportswriter Who Aided Jackie Robinson’s Entry Into Baseball Dies at 58,” December 14, 1970, 30.

43 Irv Kupcinet, Chicago Sun-Times, November 27, 1972: 40.

44 Jack Griffin, “Wendell Smith: Courage, dignity, fun,” Chicago Sun-Times, November 27, 1972: 82.

45 Bob Cromie, “Warm Memories of Wendell Smith,” Chicago Tribune, November 29, 1972: 26.

46 Brad Pye, Jr., “A Giant Is Dead,” Los Angeles Sentinel, December 7, 1972: B-5.

47 John Leusch, “Notre Dame nips DePaul by 72-67,” Chicago Tribune, January 12, 1973, C-1.

48 “Notes,” Chicago Tribune, September 17, 1983, A-5.

49 David Schneidman, “Worker, 79, to city: I do my job well,” Chicago Tribune, May 18, 1984: B-7.

50 Ben Strauss, “Friendship as Priceless as the National Pastime,” New York Times, August 22, 2012.

51 “NABJ selects Six Journalists to be inducted into NABJ’s Hall of Fame,” October 1, 2012, NABJ press release.

52 “Povich Center Announces Sam Lacy – Wendell Smith Award,” July 2013, Povich Center press release.

53 Rhiannon Walker, “Wendell Smith honored with Red Smith Award,” University of Maryland Sports Journalism Institute, May 21, 2014.

54 Fay Young, “Through the Years,” Chicago Defender, May 26, 1945: 7.

55 Bill Matney, “Jumpin’ the Gun,” Michigan Chronicle, July 19, 1947: 15.

56 A.S. “Doc” Young, “The Black Athlete in the Golden Age of Sports: Stereotypes, Prejudices, and Other Unfunny Hilarities,” Ebony, June 1969: 114-122.

57 Mark Ribowsky, A Complete History of the Negro Leagues, 1884 to 1955, (Birch Lane Press, New York, 1995), 288.

58 Wendell Smith, “The Sports Beat,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 3, 1947: 14.

59 Wendell Smith letter to Branch Rickey dated July 5, 1949, from Wendell Smith file, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

60 Wendell Smith, “Wendell Smith’s Sports Beat,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 20, 1949: 22; Wendell Smith, “Wendell Smith’s Sports Beat,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 11, 1951: 14.

61 Wendell Smith, “Wendell Smith’s Sports Beat,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 17, 1960: 17.

Full Name

John Wendell Smith

Born

June 27, 1914 at Detroit, MI (US)

Died

November 26, 1972 at Chicago, IL (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.