Wid Matthews

Wid Curry Matthews was born October 20, 1896, in Raleigh, Illinois, to William Henry Matthews Jr. and Lillie Belle (Stilley) Matthews. The family relocated to Metropolis in southern Illinois 18 months later. William had worked in the tobacco business in Raleigh, but moved the family to Metropolis for a factory job. Harry Newcomb, a family friend, later took credit for getting young Wid interested in baseball. As a child, Wid spent “many summer months” with aunts and uncles in Eldorado, IL, where he patrolled the outfield on a team of youngsters. John Upchurch was a teammate during those summers, and recalled many years later: “(Matthews) was a little guy, not a hard hitter, but aggressive and a quick thinker. He would practice sliding by the hour and would have some of us get him in the ‘hot box’ and try to tag him out…Couldn’t hardly ever tag him out.” 1]

Wid Curry Matthews was born October 20, 1896, in Raleigh, Illinois, to William Henry Matthews Jr. and Lillie Belle (Stilley) Matthews. The family relocated to Metropolis in southern Illinois 18 months later. William had worked in the tobacco business in Raleigh, but moved the family to Metropolis for a factory job. Harry Newcomb, a family friend, later took credit for getting young Wid interested in baseball. As a child, Wid spent “many summer months” with aunts and uncles in Eldorado, IL, where he patrolled the outfield on a team of youngsters. John Upchurch was a teammate during those summers, and recalled many years later: “(Matthews) was a little guy, not a hard hitter, but aggressive and a quick thinker. He would practice sliding by the hour and would have some of us get him in the ‘hot box’ and try to tag him out…Couldn’t hardly ever tag him out.” 1]

According to Sporting Life, Matthews “began to blossom as an athlete while in high school, where he was a five-letter man, shining in baseball, basketball, football, track athletics and tennis. He left school to enlist in the Navy during the war, serving his country on the U.S.S. Indiana for two years. It was while playing ball in the Navy that he attracted the attention of scouts as a promising prospect for the professional game.” 2 The USS Indiana served “as a training ship for gun crews off Tomkinsville, NY, and in the York River, VA” between 1917-19.3

The 1920 census lists his occupation as a brakeman on the railroad in Illinois. Sources indicate that he coached high school basketball and football in Caruthersville, Missouri, during baseball’s off-seasons in the years 1918—22 and 1925—284 (though some of those dates potentially conflict with his military service and work as a brakeman.)

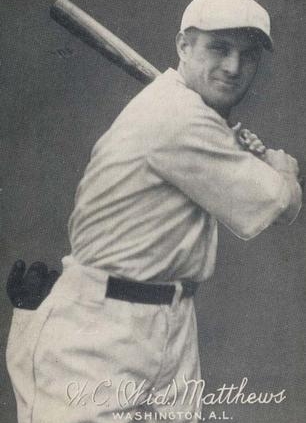

Matthews’ professional baseball playing career began in 1920 with Rochester Hustlers of the International League. His 12 years and 1,658 games as a pro were spent mostly in the minors, but highlighted by one year as a regular major leaguer in 1923 and as a part-time big leaguer in 1924 and ’25. The small (5’9”, 155 lb.), speedy Matthews manned centerfield, hit and threw left-handed, and was less known for having superior skill than for being an energetic, scrappy player. Sporting Life reported that he gained the nickname “Spark Plug,” and effused that, “In Matthews (spirit) is a sort of contagion that affects all those with whom he comes in contact –he is a sort of ‘Typhoid Mary’ of spirit and enthusiasm.”5 He bounced between Milwaukee, Toronto, and Salt Lake City minor-league teams in 1921 and ‘22.

On Philadelphia Athletics scout Harry Davis’ recommendation,6 Matthews spent the 1923 campaign with the A’s. He was the centerfielder and leadoff man for manager Connie Mack. Matthews garnered this critique from The Sporting News in August that year: “He can go a long way for a ball. He has batted well so far, but many of his hits are infield scratches, due to his fine speed…Matthews has a peculiar style in catching a ball. He catches it against his chest or stomach like a backfield man catches a punted football…(he) is the first outfielder who ever used the style. His throwing, however, is weak.”7 There’s probably a good reason that’s not a common way to catch a ball, and Matthews led all outfielders with 18 errors on the year. In spite of that, Matthews’ big-league career seemed off to a promising start thanks to a high average at the plate and he garnered some credit for imbuing the team with a verve that had apparently been missing on recent A’s teams. However, in mid-August, a “most regrettable incident took place…For the first time since he joined the Athletics, the quick-witted Matthews’ skull suddenly stopped working. Although one of the best and headiest base runners in the league, he pulled one ‘boner’ that prevented the Athletics from winning a game with Detroit. It is understood that the reprimand he received”—presumably from Mack—“when he came to the bench was remarkable for the choice of the words used and the length of the panning. Anyway ‘Spark Plug’ thought it was too strong and he talked back.”8 Matthews’ insolence did not sit well with Mack, and Matthews was punished by riding the bench for the next nine games. He was reinstated as the regular centerfielder for the remainder of the year, but his hitting tailed off.

Matthews was shipped back to the minors after the 1923 season in a trade with Milwaukee that netted the A’s future Hall-of-Famer Al Simmons. The Sporting News reported that “the fans were astounded”9 that Matthews wasn’t picked up by another major league team. Reporter J.C. Kofoed even wondered if there hadn’t been collusion to keep Matthews out of the big leagues as punishment for butting heads with Mack. Wrote Kofoed: “The kid is not a minor leaguer, and you can lay a safe bet that he will be back in fast company in 1925.”10

Matthews was back sooner than that; six weeks into the 1924 campaign, the call came from the Washington Senators, who were off to a disappointing 19-20 start while Matthews was toiling in Milwaukee. Senators boss Clark Griffith thought “Spark Plug” might help push them past mediocrity. Matthews found himself playing the outfield between two future Hall-of-Famers, Goose Goslin and Sam Rice, and rubbing elbows with teammate Walter Johnson. It went beautifully for a while: In his first game, Matthews went two-for-four with a triple and a run scored, and the Senators climbed to .500. Over Matthews’ first 19 games as a Senator, he hit .382 and the team surged from fourth to first place. In late July, The Sporting News reported, “Ever since [Matthews] joined the Washington Senators the team has been sailing along with the ease of a fugitive toy balloon. Members of the Senators willingly admit that ‘Spark Plug’ has had a lot to do with generating the spirit and punch which carried the team to the top of the American League race. Matthews is an enthusiastic little fellow, bubbling over with enthusiasm and fire—his confidence in himself being irrepressible.”11

He was an instant fan favorite, referred to as “Matty” by his “legions of local fans.”12 His initial success fell off slightly, though; according to Senators historian Tom Deveaux, Matthews got “most of his hits by pulling the ball into short right field. When defenses began adjusting, his success as a hitter diminished greatly.”13 Griffith loaned Matthews to Sacramento of the Pacific Coast League in early August 1924. Wid had played just 53 games with the Senators. The fans were not pleased: “Griffith could not have guessed the popular outcry which resulted from the move.”14 Matthews finished out the year in Sacramento, and missed out while his former teammates in Washington stormed to a World Series championship. “In an unusual gesture, the Nationals agreed that (World Series bonus) payments, albeit much smaller, should go to Wid Matthews, Wade Lefler” (another part-time player no longer with the team), “the team batboy, and the team grounds squad.”15

Matthews began 1925 back with Washington, but was used sparingly as a pinch-hitter and runner for just 10 games before being sold to Indianapolis of the American Association. Matthews’ time in the majors was over, but he still had seven years in the minors ahead of him. Between 1925—29, Matthews was able to enjoy stability as a regular with the Indianapolis Indians. He continued to be lauded for his spirit and speed: The Sporting News, previewing the Indians’ 1926 squad, commented on Matthews’ “tendency to surcharge the team with fight and his ability to cover acres of ground. Matthews may not hit as much as some of his compatriots, but he has the attribute of getting on bases somehow.”16 In 1928, Matthews and the Indians won the American Association “Junior World Series.” Matthews’ final two seasons in the minors were split between Little Rock, Chattanooga, and Reading.

He wed Willie (Graves) of Hattiesburg, Mississippi, on May 16, 1930, and retired as a player after the 1931 season at the age of 34. The couple had one child, daughter Foney Louise Matthews, nicknamed “Wiggie.” Matthews’ life in baseball was far from over, but he was away from the game for five years after retiring as a player. Matthews apparently worked in the “mercantile business” in Caruthersville, Missouri, or Metropolis, Illinois, or both during this interim.17 At some point, Hattiesburg became the family’s home, and remained so for the rest of Matthews’ life.

He returned to baseball in 1936 thanks to Branch Rickey, then business manager of the St. Louis Cardinals. The Cardinals held a tryout camp in Caruthersville, and “Matthews offered his services.”18 Rickey was pioneering the modern farm system at the time, creating a chain of Cardinals-affiliated minor league teams to stock with prospects. Matthews was named secretary-treasurer of a new Cardinals Class D affiliate in Caruthersville for the 1936 season. It was the beginning of a long association with Rickey. Matthews became a Cardinals scout and instructor in 1937, a position he held until moving to the Brooklyn Dodgers with Rickey in 1943. Matthews served as one of Rickey’s on-field instructors during spring trainings and tryout camps and as one of his top scouts through 1950. He was part of the brain trust that created the great Cardinals teams of the early ’40s and the Dodgers’ “Boys of Summer” teams of the late ’40s and early ’50s.

Being one of Rickey’s most trusted scouts in 1945 made Matthews a bit player in one of the most momentous chapters in baseball history: the signing of Jackie Robinson. By most accounts, Rickey kept nearly everyone, even his scouts, in the dark about his intention to integrate the Dodgers. Rickey announced his involvement in the launching of a new Negro league, apparently as a smoke-screen to allow him to pursue black players for the Dodgers without raising suspicion. So Matthews was probably not aware of just how significant his and other Dodgers scouts’ survey of Negro leagues talent was during that summer of 1945. As for his report on Robinson, then playing shortstop for the Kansas City Monarchs, Matthews reportedly “had his reservations about Robinson’s demeanor on the field. He was too much of a ‘hot dog’ in his mannerisms, the scout believed, but he thought he was superb at protecting the plate with two strikes on him.”19

Baseball historian Jules Tygiel made the bold claim that Matthews “would have likely resigned had he known Rickey’s intentions.”20 Research for this biography did not yield a primary source indicating whether Matthews opposed or supported integration. But Matthews did not resign from the Dodgers when they integrated, and knowingly scouted black players for the Dodgers after the fact.21 He also supposedly called Rickey “the greatest man since Jesus Christ.”22 However, another baseball historian, John Klima, charges that “there were signs throughout (Matthews’) career that he didn’t care for black players.”23 Klima seems to base this on Matthews having a “close relationship with Monarchs owner Tom Baird”24 who has a questionable record in regards to his feelings towards blacks,25 and Matthews filing a negative scouting report on Willie Mays with the Dodgers in 1949. (Many years later, Roy Campanella told The Sporting News that he had recommended Mays to the Dodgers: “‘They sent Wid Matthews out to take a look at him, but Wid said the kid couldn’t hit a curve ball,’ said Campy, his voice rising with incredulity as he added, ‘Who ever heard of any 17-year-old hitting a curve ball?’”26)

In 1950, Matthews was hired by the Chicago Cubs to be their general manager (officially “director of player personnel”). At the time of the hire, it was lauded as a coup for the Cubs due to Matthews’ association with successful Cardinals and Dodgers teams. The good will toward Matthews would not last long. He was charged with turning around a club that had lost 85, 90, and 93 games in 1947, ’48, and ’49, but the Cubs continued to be perennial losers for seven years under Matthews. Matthews claimed that the Cubs’ minor-league system was barren and that he would focus on building it up, but instead the number of farm teams declined drastically during his term. A bizarre decision was made prior to the 1951 season that the Cubs would “not take any player from (Cubs minor-league team the Los Angeles) Angels during the season without the express approval of President Don Stewart of the Angels and the Los Angeles baseball writers…if Don Stewart and (the) baseball writers feel that [a player’s] recall would hurt the Angels more than it would help the Cubs…he’ll stick with L.A.”27 At least one Cubs observer has wondered if this policy was put in place to take the pressure off Cubs owner P.K. Wrigley and Matthews to promote Gene Baker, an African American, from the Angels to the Cubs.28

In 1950, Matthews was hired by the Chicago Cubs to be their general manager (officially “director of player personnel”). At the time of the hire, it was lauded as a coup for the Cubs due to Matthews’ association with successful Cardinals and Dodgers teams. The good will toward Matthews would not last long. He was charged with turning around a club that had lost 85, 90, and 93 games in 1947, ’48, and ’49, but the Cubs continued to be perennial losers for seven years under Matthews. Matthews claimed that the Cubs’ minor-league system was barren and that he would focus on building it up, but instead the number of farm teams declined drastically during his term. A bizarre decision was made prior to the 1951 season that the Cubs would “not take any player from (Cubs minor-league team the Los Angeles) Angels during the season without the express approval of President Don Stewart of the Angels and the Los Angeles baseball writers…if Don Stewart and (the) baseball writers feel that [a player’s] recall would hurt the Angels more than it would help the Cubs…he’ll stick with L.A.”27 At least one Cubs observer has wondered if this policy was put in place to take the pressure off Cubs owner P.K. Wrigley and Matthews to promote Gene Baker, an African American, from the Angels to the Cubs.28

Another major blot on his record with the Cubs is a trade he made with the Dodgers in June 1951: Matthews dealt star Andy Pafko while getting little in return. Matthews assured fans that new Cub Eddie Miksis “will fix us,” but the trade was terribly lopsided. The Pafko trade was the worst of many moves that did not turn out well for Matthews and the Cubs. Matthews, ever the positive, energetic type, was never short on optimism for the Cubs, regardless of the results on the field. Upon Matthews leaving the Cubs, one reporter wrote that, “Wid himself, simply through his own contagious exuberance, has contributed to the fund of criticism which has come his way. Rarely have his products lived up to their advance billing, but Wid still kept praising the new ones beyond the bounds which caution should have indicated. In justice to Wid it should be added that he himself believed what he said.”29

Matthews may have had some archaic means for evaluating talent: he told The Sporting News that “one of the first things [he] does in sizing up a prospect is to shake the youngster’s hand. ‘If he has a good grip, he has one of the essentials,’ Matthews pointed out. ‘Then I pat him on the shoulder to see how muscular he is and, if I can do it jokingly, I may clutch his knee. That too,’ he said with a wink, ‘gives me an idea of his physique.’”30 But he also had progressive ideas.“I never pay any attention to the won and lost record…” he told The Sporting News. “Frequently a pitcher wins or loses because of something over which he himself has no control.”31 And, “When I look at a pitcher’s record, I look at only four columns—innings pitched, hits allowed, bases on balls and strikeouts. If the innings pitched equal the hits allowed and the strikeouts top the bases on balls, you’ve got a pretty fair pitcher.”32

Matthews’ role in the integration of the Cubs could be considered both the biggest blight and the biggest bright spot of his tenure with the club. The blight is in how long it took the Cubs to integrate. Matthews wasted no time in signing a black player to the organization—Kansas City Monarchs shortstop Gene Baker was acquired and assigned to the Cubs’ minor-league system in 1950—but no black player suited up with the big league team until late 1953. And during those three years, the Cubs failed to pursue or sign other black players. Many felt Baker deserved a promotion to the big-league team long before it finally came, and wondered if he was being held back due to his race. When the Cubs finally were ready for Baker at the tail end of the 1953 season, they followed a custom of the time by bringing in a second black player. In Matthews’ words, Baker needed a “roommate.”33 The “roommate” Matthews found for Baker was another Kansas City Monarchs shortstop: Ernie Banks. Both men arrived in Chicago at the same time, but Baker was hurt, so Banks became the first African American to play for the Cubs on September 17, 1953, almost seven years after Jackie Robinson’s major-league debut. Baker debuted three days later, now a second baseman. The Cubs were actually in the middle of the pack when it came to integration: seven clubs integrated before them, and eight after. In 1955, Matthews told the Milwaukee Journal that Banks “and Baker have been sensational. They’ve made me happy. Yes, sir, I can smile again.”34

Matthews found little success in Chicago, but he did at least deliver “Mr. Cub.” Banks apparently didn’t sense racism in the Cubs organization: Of his early days with the Cubs, Banks recalled, “The sudden association with so many white people often left me speechless and wondering why they were so kind.”35 Once the Cubs integrated, they did it well. While working to acquire Banks, Matthews told Monarchs manager Buck O’Neil, “That baseball of yours is just about over. When (it is), we want you to come work for us.”36 Matthews kept his promise, and O’Neil joined the Cubs as a scout in 1955. Cubs historian Glenn Stout has written that O’Neil “gave the Cubs a real advantage in the black community.”37

In May 1956, fed-up fans hung Matthews in effigy inside Wrigley Field. On the dummy a sign read “Down with Wid Matthews, up with the Cubs.”38 The Cubs lost 94 games that year. “Even though there were some signs of talent coming to fruition in the minor leagues, Matthews’ five-year plan was now in season number seven.”39 Matthews was asked to resign in October 1956. The Cubs never finished above .500 or higher than fifth place during his tenure. The Milwaukee Braves wasted little time in signing Matthews to oversee their scouts in November 1956. He remained with the Braves through late 1960. In early ’61, he became assistant general manager of the then-unnamed New York National League expansion team that was to become the Mets, and aided GM Charles Hurth in building the team from scratch. He remained with the Mets through the ’64 season and scouted for the California Angels in 1965. Matthews was in Los Angeles for team meetings immediately following that season when he died of a heart attack in his hotel room on October 5 at the age of 68.

Thanks to Bill Stilley for research assistance.

2 Anonymous, “A Ball Player With The Magnetic Spark,” Sporting Life (August, 1923): 8, 47.

3 www.ussindianabb01.ussindianabb58.com/history.html

4 www.semosportsweb.com/highschools/caruthersville.html, caruthersvillefootball.vnsports.com/history/irecords.asp

5 Anonymous, “A Ball Player With The Magnetic Spark,” Sporting Life (August, 1923): 8, 47.

6 Don Basenfelder, “Harry Davis, Who Topped A.L. in Homers With Eight, Keeps in Contact With Athletics, His Old Team, at 69,” The Sporting News (January 7, 1943): 5.

7 Anonymous, “Two Outstanding Recruits,” The Sporting News (August 9, 1923): 10.

8 Anonymous, “Macks Take Spite Out On White Sox,” The Sporting News (August 16, 1923): 1.

9 J.C. Kofoed, “Stove League Stories,” The Sporting News (December 27, 1923): 7.

10 J.C. Kofoed, “Stove League Stories,” The Sporting News (December 27, 1923): 7.

11 Anonymous, “‘Spark Plug’ of the Senators,” The Sporting News (July 10, 1924): 3.

12 Reed Browning, 1924: Baseball’s Greatest Season (Amherst and Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2003), 51.

13 Tom Deveaux, The Washington Senators, 1901—1971 (Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2001), 63.

14 Tom Deveaux, The Washington Senators, 1901—1971 (Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2001), 64.

15 Reed Browning, 1924: Baseball’s Greatest Season (Amherst and Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2003), 156.

16 J.F. McCann, “Necessity Makes Its Own Choices,” The Sporting News (April 8, 1926): 7.

17 Anonymous, “Wid Matthews, Former Raleigh Resident, Now Directs Player Personnel for the Chicago Cubs,” Daily Register, Harrisburg, Illinois (June 16, 1954): 1, Section 2.

18 Anonymous, “Obituaries: Wid Matthews, Rickey Aid, Boss of Cubs’ Front Office,” The Sporting News (October 16, 1965), 34.

19 Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey (Lincoln & London: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 368.

20 Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment (Oxford University Press US, 1997), 59.

21 Dave Bloom, “Beale Street’s Dancing Over Its Boy, Dan,” The Sporting News (September 3, 1947), 7.

22 Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey (Lincoln & London: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 465.

23 John Klima, Willie’s Boys (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2009): 22.

24 John Klima Willie’s Boys (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2009): 220.

25 Tim Rives, “Tom Baird: A Challenge to the Modern Memory of the Kansas City Monarchs,” In Satchel Paige And Company, ed. Leslie A. Heaphy (Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2007): 144-156.

26 Bob Broeg, “Campy, A Man Paid to Play a Boy’s Game,” The Sporting News (July 24, 1971), 20.

27 Anonymous, “Scribes to Be Given Voice in Angel Shifts—Matthews,” The Sporting News (November 29, 1950): 7.

28 Gleenn Stout, The Cubs (Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2007): 215.

29 Anonymous (clipping from Baseball Hall of Fame file on Matthews), “No Mathews Contract” (sic), publication unknown (October 12, 1956): page unknown.

30 Anonymous, “Shake His Hand, Matthews’ No. 1 Rule Picking Rookie,” The Sporting News (March 15, 1950): 8.

31 Edgar Munzel, “Up-and-Down Warren Hacker Up With Cubs for Keeps This Time,” The Sporting News (October 31, 1951): 7.

32 Bob Wolf, “Wid Wallops ERA as Inaccurate Hill Gauge,” The Sporting News (February 17, 1960): 14.

33 Peter Golenbock, Wrigleyville (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996): 347.

34 Sam Levy, “Cubs’ Wid Matthews Winning New Respect,” The Milwaukee Journal (May 22, 1955): page unknown.

35 Peter Golenbock, Wrigleyville (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996): 350.

36 Buck O’Neil with David Conrads and Steve Wulf, I Was Right On Time (New York, London, Toronto, Sydney: Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, 1997): 191.

37 Glenn Stout, The Cubs (Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2007): 239.

38 Anonymous (clipping from Baseball Hall of Fame file on Matthews), “Wid, Wife See Fans ‘Hang’ Him,” publication unknown (May 31, 1956): page unknown.

39 Glenn Stout, The Cubs (Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2007): 230-231.

Full Name

Wid Curry Matthews

Born

October 20, 1896 at Raleigh, IL (USA)

Died

October 5, 1965 at Hollywood, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.