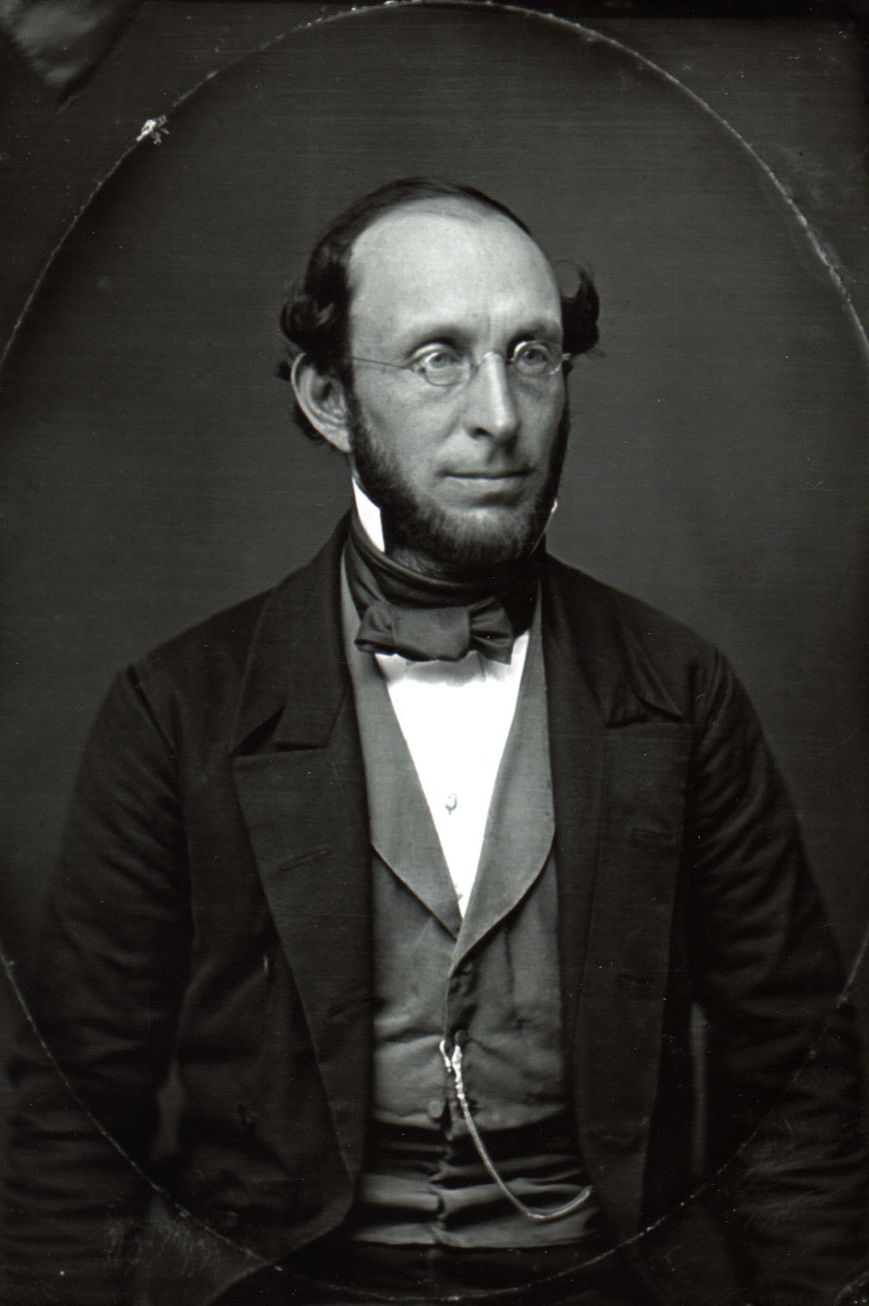

William Wheaton

William Rufus Wheaton was born in New York City on May 7, 1814. Part of his education was achieved at the Union Hall Academy, located on the corner of Madison Avenue and Oliver Street. After graduation, Wheaton read law with John Leveridge, a well-known East Side attorney. Wheaton was later admitted to practice by Chancellor Walworth in his Court of Chancery. (New York State adopted a new constitution in 1848, which abolished the Court of Chancery and the Office of the Chancellor.) Later, Wheaton passed an examination for admission to the New York State Supreme Court. He then formed a law partnership with Ebenezer Griffin.

William Rufus Wheaton was born in New York City on May 7, 1814. Part of his education was achieved at the Union Hall Academy, located on the corner of Madison Avenue and Oliver Street. After graduation, Wheaton read law with John Leveridge, a well-known East Side attorney. Wheaton was later admitted to practice by Chancellor Walworth in his Court of Chancery. (New York State adopted a new constitution in 1848, which abolished the Court of Chancery and the Office of the Chancellor.) Later, Wheaton passed an examination for admission to the New York State Supreme Court. He then formed a law partnership with Ebenezer Griffin.

At the age of twenty-two, Wheaton married Elizabeth A. Jennings on February 1, 1837, in New York City. For a wedding present, William gave his bride a red shawl from India. Elizabeth was known to wear the shawl whenever the two of them went out together. In all, they had seven children.

Wheaton practiced law during the 1830s and 1840s in New York. He was also a member of the mayoral nominating committee for the Democratic Whig party of New York’s Tenth Ward in 1842. Later in 1848, he was a member of the committee in the Tenth Ward to nominate the Whig candidate for Congress from the Fourth Congressional District.

In addition to practicing law, Wheaton involved himself with playing sports, such as baseball and cricket. William Wheaton was interviewed for an article that appeared in San Francisco’s The Daily Examiner in 1887. The article was entitled “How Baseball Began – A Member of the Gotham Club of Fifty Years Ago Tells About It.” Wheaton begins by saying that he lived at the corner of Rutgers Street and East Broadway in New York during the 1830s. In 1836, he had just passed the bar exam and become a lawyer, and he was “very fond of physical exercise.” (See Appendix for the majority of the article.)

A founding member of the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club in New York in 1845, Wheaton became the club’s first vice-president. He also served on the Committee of By-Laws that year along with William H. Tucker. However, given the fact that he was playing for the Brooklyn Star Cricket Club in 1847 and the Eclipse and New York cricket clubs in 1848, one wonders why he abandoned his beloved game of baseball.

By 1849 Wheaton caught gold fever. He sailed on the bark Strafford with the New York Mining Company, leaving his wife and children in New York–a not uncommon practice at the time. Wheaton and one hundred men of the mining company left New York on February 1, 1849, and arrived at San Francisco on August 30.

When he arrived at Sutterville, William Wheaton went to Dry Town, where he worked for a short time at mining. This venture did not last long, and he went back to Sacramento, where he conducted a mercantile business with Alonzo Hamilton under the name of Hamilton & Wheaton. The partnership dissolved after two years, but Wheaton moved to San Francisco, where he continued in the same business for another year, occupying a store on Battery Street near Jackson Street.

After his final year in the mercantile business, Wheaton returned to the practice of law, and opened up a law office on Montgomery Street. After two years, he voyaged to New York in the winter of 1850/51. After nearly another two years, he returned to San Francisco and soon began to practice law again, opening an office on Montgomery Street. Wheaton’s wife, Elizabeth, traveled to San Francisco in 1852 to be with her husband for an extended stay, leaving their children with Wheaton’s parents in New York. Wheaton continued practicing law until 1855, and then returned to New York for a visit. Back in San Francisco in 1856, Wheaton became deeply involved with the Committee of Vigilance, whose purpose was to rein in rampant crime and government corruption and whose practices skirted the Constitution. Members used Committee headquarters for the interrogation and incarceration of suspects, whom they denied the right of due process. The Committee engaged in policing, investigating disreputable boarding houses and vessels, deporting immigrants, and parading its militia.

The Society of California Pioneers was established in 1850 in San Francisco, and William Wheaton served as an officer of the society, including secretary in 1860 when he was an attorney on Washington Street. In 1857, Wheaton was Aid-in-Chief for a march that was organized to celebrate Admissions Day of the Society of California Pioneers. The march began on Market Street in San Francisco and ended at the American Theatre on Sansome Street. He also was the secretary for the Committee of Management for the Pioneer Society’s meeting and assembly rooms.

Wheaton was secretary of the Pioneer Chess Club in 1856, and wrote a piece about a chess tournament that was published in the Daily Evening Bulletin (later the San Francisco Bulletin) on March 17, 1858. It stated that the Pacific Chess Tournament would be held in the large assembly room at the southeast corner of Sacramento and Kearny Streets, and that he was responsible for admitting competitors to the tournament.

Elizabeth Wheaton and their four daughters moved to San Francisco permanently in 1860. Their son, George Henry Wheaton joined them in 1865 after serving in the Civil War as a judge-advocate and reaching the rank of major.

William Wheaton was elected City and County Assessor in 1861 and 1863 by the People’s Party. He served two successive terms. He was also chosen to represent the citizens of San Francisco in the California State Legislature in 1862. Other important posts included Chairman of the Committee of the Political Code for the Union party, chairman of the San Francisco Delegation, and chairman of the Ways and Means Committee during 1871-1873. As chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, Wheaton was influential in securing the appropriation for the building of the University of California, otherwise known as Berkeley.

Wheaton also served as the General Manager of the California Life Insurance Company in 1872, and was appointed by President Grant as the Register of the General Land Office of the United States in 1876. Four years later, President Hayes reappointed Wheaton. Presidents Garfield (and presumably President Arthur after Garfield’s assassination) and Cleveland continued to appoint him. Wheaton finally resigned from office in 1886.

Wheaton was also involved as a Masonic member of California Lodge No. 1. Moreover, he was a member of the Knights Templar, Odd Fellows Lodge No. 123, and the St. Andrew’s Benevolent Society.

William and Elizabeth celebrated their golden wedding anniversary on February 1, 1887, and a gold spoon commemorated the occasion. William Rufus Wheaton died September 11, 1888, at the age of seventy-four.

Appendix

“In fact we all were [fond of physical exercise] in those days, and we sought it wherever it could be found. Myself and intimates, young merchants, lawyers, and physicians found cricket too slow and lazy a game. Three-cornered cat was a boy’s game, and did well enough for slight youngsters, but it was a dangerous game for powerful men, because the ball was made of a hard rubber center, tightly wrapped with yarn, and in the hands of a strong-armed man it was a terrible missile, and sometimes had fatal results when it came in contact with a delicate part of the player’s anatomy.

“We had to have a good outdoor game, and as the games then in vogue didn’t suit us, we decided to remodel three-cornered cat and make a new game. We first organized what we called the Gotham Baseball Club. This was the first ball organization in the United States, and it was completed in 1837. Among the members were Dr. John Miller, a popular physician of that day; John Murphy, a well-known hotel-keeper, and James Lee, President of the New York Chamber of Commerce.

“The first step we took in making baseball was to abolish the rule of throwing the ball at the runner and ordered that it should be thrown to the baseman instead, who had to touch the runner with it before he reached the base. During the regime of three-cornered cat there were no regular bases, but only such permanent objects as a bedded boulder or an old stump, and often the diamond looked strangely like an irregular polygon. We laid out the ground at Madison square [sic] in the form of an accurate diamond, with home-plate and sand bags for bases. You must remember that what is now called Madison square [sic], opposite the Fifth Avenue Hotel, in the thirties was out in the country, far from the city limits. We had no short-stop, and often played with only six or seven men on a side. The scorer kept the game in a book we had made for that purpose, and it was he who decided all disputed points. The modern umpire and his tribulations were unknown to us. We played for fun and health, and won every time. The pitcher really pitched the ball and underhand throwing was forbidden. Moreover he pitched the ball so that the batsman could strike it and give some work to fielders. The men outside the diamond always placed themselves where they could do the most good and take part in the game.

“After the Gotham club had been in existence a few months, it was found necessary to reduce the rules of the new game to writing. This work fell to my hands, and the code I then formulated is substantially that in use today. We abandoned the old rule of putting out on the first bound and confined it to fly catching. The Gothams played a game of ball with the Star Cricket Club of Brooklyn, and beat the Englishmen out of sight, of course. That game and the return were the only matches ever played by the first baseball club.

“The new game quickly became very popular with New Yorkers, and the numbers of the club soon swelled beyond the fastidious notions of some of us, and we decided to withdraw and found a new organization, which we called the Knickerbocker. For a playground we chose the Elysian Fields of Hoboken, just across the Hudson River. And those fields were truly Elysian to us in those days. There was a broad firm, greensward, fringed with fine shady trees, where we could recline during intervals, when waiting for a strike, and take a refreshing rest.

“We played no exhibition or match games, but often our families would come over and look on with much enjoyment. Then we used to have dinner in the middle of the day, and twice a week we would spend the whole afternoon in ball play. We were all mature men and in business, but we didn’t have too much of it as they do nowadays. There was none of that hurry and worry so characteristic of the present New York. We enjoyed life and didn’t wear out so fast. In the old game when a man struck out those of his side who happened to be on the bases had to come in and lose that chance of making a run. We changed that and made the rule which holds good now.

“When I saw the game between the Unions and the Bohemians the other day, I said to myself—If some of my old playmates who have been dead forty years could arise and see this game they would declare it was the same old game we used to play in the Elysian Fields, with the exception of the short-stop, the umpire, and such slight variations as the swift underhand throw, the masked catcher, and the uniforms of the players. We started out to make a game simply for safe and healthy recreation. Now it seems, baseball is play for money, and has become a regular business.”

Sources

Daily Alta California September 9, 1857.

In Memoriam, William R. Wheaton, 1888.

Written by members of the San Francisco Bar Association

“How Baseball Began – A Member of the Gotham Club of Fifty Years Ago Tells About It.” San Francisco Examiner. November 27, 1887. (Wheaton’s name does not appear anywhere in the article, but presumably he is the speaker. Randall Brown, who found the article several years ago, concludes that Wheaton is the speaker. He bases his conclusion on five points. First is through a process of elimination: Wheaton was the only Knickerbocker organizer to settle in California. Second, the career description in the article fits, as Wheaton was an attorney and it’s logical that he would describe himself as a “pioneer.” Third, the cricket bat is confirmed by Spirit of the Times. Fourth, Wheaton did live at Rutgers and East Broadway for a time; according to directories of the time, he moved rather frequently. Fifth, Wheaton’s presence as an umpire at two New York-Brooklyn matches agrees with his reference to them.)

Kibbey, Mead B. Sacramento City Directory for the Year 1851 with a History of Sacramento to 1851, Biographical Sketches, and Informative Appendices. Sacramento: California State Library Foundation, 2000.

Statement of Facts on Early California History made by William R. Wheaton, 1878

The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Sullivan, G. W. Early Days in California: The Growth of the Commonwealth under American Rule, with Biographical Sketches of Pioneers. Volume I. San Francisco: Enterprise Publishing, 1888.

Other acknowledgments: John Wheaton (great-great-grandson), John Thorn, Randall Brown, Angus Macfarlane, David Block, and Jan Finkel

Photo Credit

Photo is courtesy of Bruce Marshall (great-great grandson).

Full Name

William Wheaton

Born

May 17, 1814 at New York, NY (US)

Died

February 1, 1887 at , ()

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.