1905 Ogden Assembly Club Baseball Team

This article was written by Chris Hansen

Introduction

On Saturday, March 25, 1905, a small yet curious article appeared in the Salt Lake Telegram that announced a baseball game to be played the following day between the Salt Lake Browns and the Ogden Chocolates at Walker’s Field in Salt Lake City.1 This would be the first formally organized game of baseball between two Black teams in Utah since 1897, when the Fort Douglas Browns played Bruce Johnson’s picked nine, the Black Rubes. It also was the beginning of what became known as the Assembly Club baseball team of Ogden, the city’s first all-Black ballclub.2

The history of Black baseball in Utah began in earnest with the Fort Douglas Browns. A talented and well-respected team, the 1897 Browns were drawn from the African American 24th Infantry Army Regiment stationed at the fort situated a few miles east of Salt Lake City. This squad laid a foundation for Black ballclubs to come.3 Evidence of this came in a 1908 newspaper editorial by Hal Hayden, manager of the Salt Lake Occidentals, a prominent Black baseball team between 1906 and 1911 that arose from the Assembly Club squad. Hayden dubbed the Fort Douglas team the “best team in the history of Salt Lake Baseball.”4

In conjunction with the Browns in 1897, Bruce Johnson, a well-known political figure and businessman in the Utah African American community at the turn of the twentieth century, put together the Black Rubes baseball team specifically to challenge Fort Douglas.5 With the Browns leading the way, 1897 was a banner year for Black baseball in Utah. A third club, the Salt Lake Monarchs, briefly fielded a team captained by Charles Catlin6; and a fourth club, the Fort Duchesne 9th Cavalry, also put together a lineup that faced the Fort Douglas Browns.7

Few Black teams were in Utah between 1897 and 1905. One noteworthy nine was the Keith O’Brien Browns of 1903, who were backed by the local retailer of the same name.8 The Salt Lake Americus Club, an African American social organization similar to the Assembly Social Club in Ogden, took over sponsorship of the KOB team in 1904.9 Those early teams were structured loosely and played intermittently.

Then, in 1905, the Salt Lake Browns and the Ogden Chocolates played a game against each other. More significantly, they united soon after to become the Ogden Assembly Club baseball team for one noteworthy season. According to the Salt Lake Tribune, they were the “strongest amateur aggregation in the State.”10

The Assembly Club Social Organization

The Ogden Assembly Club, established in 1902, was an African American association incorporated to “promote social intercourse among its members and associates.” It included African Americans who primarily lived in and around Ogden.11 The social club, which organized the 1905 baseball team, catered to the large population of porters and waiters who made their way to the Junction City via the railroad. Ogden was a popular resting spot for many Blacks from across the nation who worked the railroad because of the city’s geographic location; clubs, such as the Assembly Club, that accommodated them; and amenities, such as “a dismantled Pullman car in the middle of the [Union Station] freight yard where porters could lodge.”12

The Assembly Club formed from the ashes of a previous social club, known as the Eureka Club, founded two years prior, in 1900. It boasted a membership of 44 “people of color.”13 Census numbers in 1900 show 43 Blacks lived in Ogden. Over the next decade, that figure more than quadrupled, with 204 enumerated in 1910. The Eureka Club, and then the Assembly Club, was housed at 149 25th Street.

Lower 25th Street, located near the railroad hub and Union Station, was the heart of the segregated Black and immigrant population in Ogden. As 25th Street historian Val Holley noted: “One of the railroads’ most enduring legacies in Ogden is the coalescence of an African American community in the blocks near the Union Station.”14 The two-story club building, which was visible as one departed the train at Union Station, featured a saloon, clubrooms, cold and hot baths, a café, and a barbershop.

Many notable Utah African Americans were involved with the club. Most of them, along with the players they sponsored in 1905, were born in the South during the Civil War or Reconstruction era. They spent their formative years during the early Jim Crow period and made their way to Ogden via train at the turn of the twentieth century.15

Owing to excessive restrictions by the city, clampdowns by the police, gambling arrests, liquor license violations, and the passing of Prohibition in Utah in 1917, the Assembly Club closed in 1918. Those associated with the club then ventured on to California, Idaho, or Washington, while others moved eastward to Chicago, Denver, or Kansas City, Missouri.

The Assembly Club Baseball Team’s Origins

The Assembly Club was interested in athletics largely as a business opportunity but also for entertainment and a sense of pride, and it became involved in organized sports in 1904 when it hosted boxer Rufe Turner from Stockton, California.16 Turner lodged at the Assembly Club building, and the club provided him with a place to train on the second floor before his fight against Boston’s Barney Mullin. Turner handily defeated Mullin, and this was the first of many quality fights the Assembly Club hosted over the years. Boxing was popular in Ogden in the early 1900s, and Black baseball and boxing often crossed paths.

By 1905, baseball in Ogden and Utah had never been so popular.17 That season, the Ogden Lobsters joined the Pacific National League (PNL), a professional minor league that rivaled the Pacific Coast League between 1903–1905.18 Ogden had fielded baseball teams since 1870, and although they were almost exclusively all-white squads, Black players occasionally took part. For example, in 1890, future boxing great Robert “Bobby” Dobbs caught for the semipro Ogden club.

It was under these auspices, and after the Salt Lake Browns and Ogden Chocolates game in March 1905, that the Ogden Assembly Club baseball team officially formed. George Dover—the Assembly Club’s social club proprietor, baseball team manager, and occasional first baseman—took his pick of players from the Browns and the Chocolates.

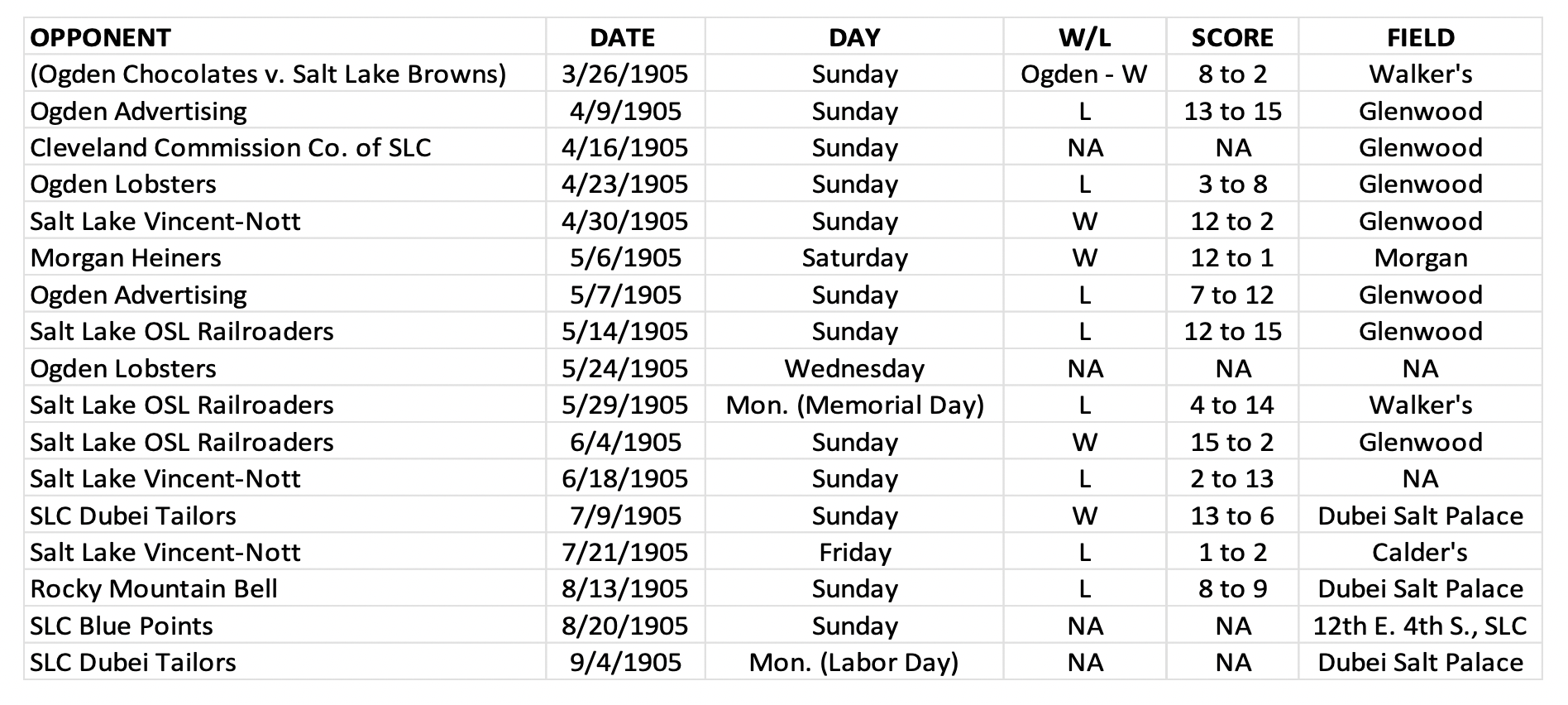

The Assembly Club Baseball Team’s 1905 Season

The 1905 season was the only complete year Assembly played ball. After the March 25 game between the Browns and Chocolates, the newly combined Assembly team played the Ogden Advertising Club April 9 in an exhibition game. The Ads were composed of some of Ogden’s best white semipro and amateur talent. These players used this game, in part, to showcase their skills for potential slots on the Ogden Lobsters minor-league team.

The well-attended game at Ogden’s Glenwood Park was evenly divided between Black and white fans. Assembly lost 15–13, not exactly a Deadball Era score. Despite the close score, Assembly still was a largely inexperienced group of players. The Ogden Standard quipped that Assembly appeared to be “bamfuzzled” at times during the game by the Ads and joked about one of their players who inexplicably slid into first base:

“[He] Evidently forgot that there is no need of touching the batter on his way to first and shutting his eyes and aiming straight for a craggy point in the distant Wasatch, he launched forth through the air while the grandstand laughed themselves hoarse.”19

Only a brief mention was in the newspaper about Assembly’s April 16 game against the Cleveland Commission amateur team from Salt Lake City; however, Hays Gann, Assembly’s ace, had a solid outing. This was followed by a game on April 23 against the renowned Lobsters, the team’s first exhibition game of the year. In its reporting of the game, the Salt Lake Tribune stated that the Lobsters won 8–3 and that their pitcher, Hastings, “made monkeys out of all who faced him.”20

Newspaper coverage tended to be inconsistent overall, but they did a good job covering Assembly and regularly praised their play while keeping interest in the team high (albeit with racist overtones, as the “monkeys” remark could well be interpreted). No other Utah Black sports entity before Assembly received as much press, with dozens of articles written about the team during its 1905 season.

On April 30, Assembly played its first of several games against the Vincent-Notts Shoe Company team from Salt Lake City at Glenwood Park. Vincent-Notts was the top team in the amateur Salt Lake City-based Commercial League, but Assembly easily won 12–2 in front of a large crowd. The Denver & Rio Grande Railroad even ran special rates for Salt Lake City fans to attend the game in Ogden.21 After the train arrived in Ogden, a trolley car took fans directly to Glenwood Park.

For the only Saturday game of the year, on May 6, Assembly went to Morgan City to play the local amateur team, dubbed the Heiners. Assembly effortlessly won as “the locals were badly outclassed.”22 The Heiners were made up of nine brothers coached by their father, Daniel Heiner, a prominent merchant, property owner, politician, and ecclesiastical leader in Morgan City.23 Assembly had difficulty returning to Ogden from Morgan City for the Sunday game against the Ogden Advertisers, however. Thus, Assembly was unprepared and lost to the Ads again, by a score of 12–7. Amid defeat, Assembly flashed some outstanding play:

“The most spectacular play of the game that set the grandstand to howling with enthusiasm was a pretty catch by Robinson, the colored shortstop. Leavitt hit a hot liner straight out, close to second bag; it looked like a safe hit, but Robinson with a bound reached out until it appeared as though he were going to fall and when he righted himself the horsehide was snugly tucked in his big mitt.”24

The Daily Utah State Journal also pointed out that “this particular colored boy is one of the best short stops that ever wore an amateur uniform on the Ogden diamond, he covers the ground in good shape and is as sure as most of them in like position.”

On Sunday, May 14, Assembly hosted the Salt Lake City-based Oregon Short Line (OSL) Railroaders at Glenwood Park. Assembly played this and most of its games for money, because the team was as much as anything a business endeavor of the Assembly Club. The Friday edition of the Ogden Morning Examiner noted that both teams were so confident about winning that they posted an additional side bet of $50 to the sports editor of the newspaper.25 In what the Salt Lake Herald dubbed a “swatfest” and the Tribune criticized as a game that featured “as many errors as dogs have fleas,” OSL scored big and took the haul as the Railroaders defeated Assembly, 15–12.26

After a midweek practice game against the Lobsters, Assembly played twice more against OSL. The first game took place on Monday, May 29, at Walker’s Field in Salt Lake City. Gann and Assembly lost 14–4. Then, on Sunday, June 4, at Glenwood Park, Assembly won behind pitcher Lawrence, with a final of 15–2. Denver boxer Charles “Kid” Bell made a guest appearance for Assembly while in town for a boxing match.27 Both games were played amid hefty side bets and featured a sideshow of vaudevillian or burlesque “shadow ball” performances by Assembly players to entertain spectators and lure fans to future games.28 The Salt Lake Telegram described the game’s performance:

“It would have done Minstrel George Thatcher good to have heard the way the dark-skinned players coached their brunette brethren on how to play the national game. They yah, yah, yah’d and sang and danced from jig to ragtime. They sang snatches of ‘coon’ songs and gave an impromptu darktown vaudeville show along with their ball playing.”29

Assembly then took a couple weeks off. Opponents were in their regular seasons, and games against new teams were difficult to schedule. Assembly next played at Glenwood Park on June 18 against Vincent-Notts and was defeated 13–2, with the “shoe boys” by all accounts being in championship form.30

After an easy win against the Salt Lake City Dubei Tailors in a rare Friday game on July 9 at the new Salt Lake City Salt Palace Park, Assembly had a rematch with Vincent-Notts, on July 23. Gann, Assembly’s go-to pitcher, sent word to the Salt Lake Tribune just before the game that:

“He is personally prepared to wipe the ground with the Vincent-Notts club at Calder’s Park this afternoon and make the shoe peddlers look like seventeen cases of misfits. There will be a barbeque and the shoe fellers can have what is left of the ox to make oxfords for the rest of the summer.”31

The barbecue was sponsored and hosted by the African Methodist Episcopal and Calvary Baptist African American churches in Salt Lake City. Alas, Assembly did not have much to celebrate: Vincent-Notts continued its winning streak in a pitcher’s duel, with the shoe company’s Romney defeating Gann by a more Deadball Era score of 2–1.32

As the season carried on, Assembly played fewer games, playing only two in August. One, against the Rocky Mountain Bell company team, was a 9–8 loss.33 The other, against the Salt Lake City Blue Points, went without a reported a score.34 Assembly’s final game came on Labor Day, September 9, against the Dubei Tailors. Again, the score was unreported. The season-ending Tailors game was one of several features during a free day of entertainment at Salt Palace Park, with the Assembly team now an attraction.35

After a rough start, Assembly eventually found its way during the 1905 season, roughly splitting wins and losses while dividing play between its home field in Ogden and different parks around Salt Lake City.

The team earned the respect of newspapers and fans in northern Utah. There were no issues with fighting, unfair play, and other problems, as some worried. Although teams and leagues were segregated, numerous clubs, at varying levels and in different leagues throughout the state, were willing to play Assembly for money and experience against a quality team.36 A final breakdown of Assembly’s 1905 season:

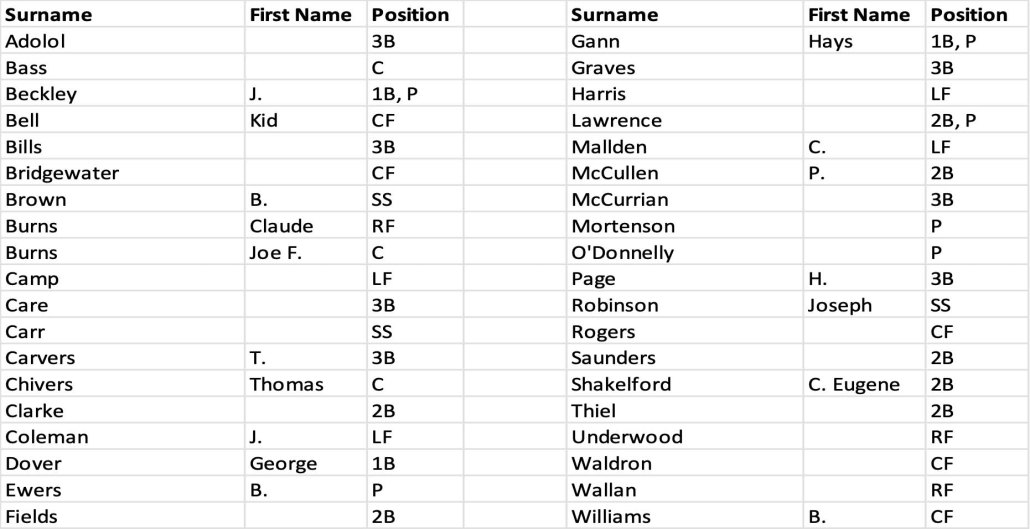

The Ballplayers

Assembly provided many athletes with the opportunity to play baseball, so there was a great deal of interest. The team fielded more than three dozen different players over the course of the 1905 season. It featured men from Ogden, Salt Lake City, and surrounding areas, as well as some who passed through Ogden while working for the railroad as word of the opportunity to play ball in the Beehive State certainly passed through the trains. The following players made appearances:

The stars of the Assembly team (and later with the Salt Lake Occidentals) included:

- Claude Burns, a versatile athlete who played across the outfield and was known as a strong hitter. Burns led the Utah State League in hitting in 1908 for the Occidentals and later played for the Portland Hubbard Giants in 1914.

- Joe Burns, Assembly’s (and the Occidentals) catcher and assistant manager. Joe Burns also was a boxing promoter who worked with several fighters, including Jack Johnson.

- Hays Gann, the Assembly and Occidentals ace pitcher. Gann appeared in more than half of Assembly’s games and had played for the KOB-Americus Club team in Salt Lake City in 1904.

- Joe Robinson, Assembly’s stellar shortstop and later Utah League All-Star second baseman with the Occidentals. Robinson made his way to Ogden from Spokane, Washington, where he had been a boxer.

The Ball Field

Assembly had several ingredients that ensured the team’s success. It had high-caliber players and was able to schedule a full season of games, largely thanks to the diligence of the charismatic business manager, George Dover.37 More important, Assembly was able to secure Glenwood Park, Ogden’s finest field. Assembly played multiple games there against Ogden rivals the Lobsters and Advertisers and was able to use the facility to play home games against Salt Lake City teams.

The Glenwood Park (now known as Lorin Farr Park) baseball field was located across the street from the main park entrance near 16th and 17th Streets and Madison Avenue and Canyon Road. Jack Greenwell, a prominent white semipro player in Ogden during the turn of the twentieth century, noted during an interview on baseball history in Ogden:

“The field was across the road, north, from Glenwood. Altman’s Greenhouse [located at 770 Canyon Road] was right next to the diamond and every time we broke a pane of glass the team had to pay 25 cents and Mr. Altman gave the ball back so everyone was satisfied.”38

Operated by a private entity in 1905, the field eventually became a public park in the 1910s. Although located on the outskirts of town, the streetcar route that ran from downtown Ogden and connected to the major rail lines throughout the city made the park accessible. Glenwood Park was a major destination point along the transit route.

Early Twentieth Century Black Baseball in the Western United States

Assembly had a collection of talented players largely brought together by the railroad, a number of quality opponents in northern Utah, a well-organized entity that supported it, a respectable fan base, and good fields to play on. Thus, the club had one of the most productive Black baseball seasons in the western United States in 1905. Although few professional Negro teams existed at the time in the United States, many amateur, independent, and barnstorm teams akin to Assembly played ball. Western teams outside Utah formed in the era (1902–1908) include:

Indeed, Black baseball in the western United States was alive and well in the early 1900s. The teams’ affiliations ranged from military forts to mining and railroad interests, as well as other working-class urban and rural communities. As such, these teams were a reflective slice of US society and culture. Assembly, a prime and successful example, played a vital role within that mix, just as the team’s successors, the Occidentals, would over the next several years.

Conclusion

Although it was not a professional club, Assembly was a local byproduct of the larger phenomenon of Black baseball growth during the early 1900s. The time was right for a serious Black team in Utah. Assembly was that team and the beginning of something bigger.

Assembly did not disband in 1906; it reformed as the Salt Lake City Occidentals. The majority of the new Occidentals team consisted of former Assembly players. Just as Gann and Burns did much of the battery work for Assembly in 1905,39 they did the same for the Occidentals in 1906.40 Joe Burns was assistant manager for Assembly and then with the Occidentals.

Both teams played many of the same opponents, with the Occidentals’ first game of the 1906 season coming against old Assembly rival Vincent-Notts. The Occidentals made regular visits to Glenwood Park.41 When previous Assembly players later joined the Occidentals, newspapers made it a point to recognize that player as being formerly of Assembly fame.42

Just as with the Assembly Social Club in Ogden, Black social clubs connected with Joe Burns in Salt Lake City sponsored the Occidentals.43 It made sense that as the team evolved they moved to Salt Lake City, which was the epicenter of the still-limited Black population in Utah at the time.44 Not to mention, there were more teams to play against and fields to play on in the capital city.

The Assembly Club had ties to the Americus social club in Salt Lake City, which was affiliated closely with the Occidentals.45 Americus was connected to Bruce Johnson,46 who organized and managed the 1897 Black Rubes team who had played against the Fort Douglas Browns. The 1905 Assembly baseball team, along with its 1906-1911 Salt Lake City Occidentals successors, also laid a foundation for later teams, such as:

- The 1920s–1930s Salt Lake Tigers, who changed their name to the Occidentals in the late 1930s to honor the earlier team;

- The 1940s–1950s Salt Lake Monarchs, who also later changed their name to the Occidentals;

- The late-1940s Sahara Village Giants, from Hill Air Force Base, featuring all-star outfielder Algie Bell, who often played the Salt Lake Monarchs/Occidentals; and

- Teams off the Wasatch Front, such as the 1943 Sunnyside Monarchs, who played in the integrated Carbon Coal League and were led by second baseman and pitcher Andy Pearson.

All of these teams formed a legacy of Black baseball in Utah and the West that deserves a closer look.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Dr. Chris Merritt and Sylvia Newman for early reviews of this paper, and a big thanks to Ron Auther of the Shadow Ball Express Blog, who helped to provide insight on African American baseball in the US West.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Will Christensen and fact-checked by William H. Johnson.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited below, the author drew upon:

Lanctot, Neil. Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

Lomax, Michael E. Black Baseball Entrepreneurs, 1902-1831: The Negro National and Eastern Colored Leagues. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2014.

Moore, Louis. I Fight for a Living: Boxing and the Battle for Black Manhood, 1880 – 1915. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2017.

Newman, Roberta J. and Joel Nathan Rosen. Black Baseball, Black Business: Race Enterprise and the Fate of the Segregated Dollar. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2014.

Papanikolas, Helen Z. (ed.) The Peoples of Utah. Salt Lake City, UT: Utah State Historical Society, 1976.

Ribowsky, Mark. A Complete History of the Negro Leagues, 1884 to 1955. New York City: NY: Kensington Publishing Corporation, 1998.

Riess, Steven A. Touching Base: Professional Baseball and American Culture in the Progressive Era, Revised Edition. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1999.

Notes

1 “Colored Gentlemen Cross Bats on Sunday,” Salt Lake Telegram, March 25, 1905: 7.

2 “Colored Baseball Club,” Salt Lake Tribune, April 7, 1897: 1.

3 Ron Auther, “The Fort Douglas Browns – History of the Men of the 24th Infantry Regiment,” The Shadow Ball Express, August 7, 2017. https://shadowballexpress.wordpress.com/2017/08/04/the-fort-douglas-browns-history-of-the-men-of-the-24th-infantry-regiment-part-1/

4 “Occidental Manager Replies to a Fan on Negro Baseball,” Salt Lake Telegram, April 25, 1908: 9 and 12.

5 “Utah News,” Davis County Clipper, April 16, 1897: 2.

6 “Colored Nines Play,” Salt Lake Tribune, May 30, 1897: 7.

7 “Close Ball Game,” Salt Lake Tribune, May 6, 1897: 2.

8 “Black Ball Players Lost,” Salt Lake Tribune, June 25, 1903: 8.

9 “Keith O’Brien Victory,” Salt Lake Herald, June 25, 1904: 7.

10 “Ogden’s Colored Ball Team,” Salt Lake Tribune, May 6, 1905: 2.

11 “Assembly Club,” Articles of Incorporation, Utah State Archives Collection, January 30, 1902.

12 Larry Tye, Rising from the Rails: Pullman Porters and the Making of the Black Middle Class (New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company, 2004), 56.

13 “Colored Club Incorporates,” Salt Lake Tribune, September 27, 1900: 7.

14 Val Holley, 25th Street Confidential: Drama, Decadence, and Dissipation (Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press, 2013), 10.

15 Individuals involved in running the club included: William Carter, George Dover, Clarence Ernest, Lawrence Fair, William Housbon, Samuel Pool, Frank Turner, and Charles Woods.

16 “Local Prize Fight a Frost,” Ogden Morning Examiner, August 24, 1904: 8.

17 “Baseball Draws Record Crowds,” Salt Lake Herald, December 31, 1905: 35.

18 “Baseball Sunday,” Ogden Morning Examiner, April 27, 1905: 8. Also, “Pacific National League.”

www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Pacific_National_League

19 “Advertisers Win First Game,” Ogden Standard, April 10, 1905: 7.

20 “Trying Out His Men,” Salt Lake Tribune, April 23, 1905: 13.

21 “Vincent-Notts to Play Ball in Ogden,” Salt Lake Telegram, April 28, 1905: 9.

22 “Colored Gents Beat Heiners,” Salt Lake Tribune, May 7, 1905: 29.

23 “Ogden Brevities,” Ogden Morning Examiner, June 9, 1904: 5.

24 “Amateur Game,” Daily Utah State Journal, May 8, 1905: 6.

25 “Game to be Played Sunday is for Side Bet,” Ogden Morning Examiner, May 13, 1905: 6. According to an inflation calculator, $50 in 1905 equaled $1,500 in 2022.

26 Salt Lake Herald, May 15, 1905: 7.

27 “Colored Boxer Here,” Daily Utah State Journal, June 6, 1905: 6. “Gardner Training,” Salt Lake Tribune, June 7, 1905: 7.

28 Lawrence D. Hogan, Shades of Glory: The Negro Leagues and the Story of African American Baseball (Washington, DC: National Geographic, 2006), 371.

29 “Oregon Short Line Defeats Colored Team,” Salt Lake Telegram, May 31, 1905: 8.

30 “Vincent-Notts Still in Championship Form,” Salt Lake Telegram, June 19, 1905: 8.

31 “Game at Calder’s Park,” Salt Lake Tribune, July 21, 1905: 8.

32 “Colored Folks’ Outing,” Salt Lake Herald, July 22, 1905: 3.

33 “Hello Boys Victors,” Salt Lake Telegram, August 14, 1905: 7.

34 “Assembly Club vs. Blue Points,” Salt Lake Herald, August 20, 1905: 5.

35 “Entertainment for Salt Palace Patrons,” Salt Lake Telegram, September 1, 1905: 10.

36 This opened the door to eventually allowing the Salt Lake City Occidentals to join the Utah State League in 1908 and winning it in 1909. It also is worth noting that some teams were unwilling to play, despite repeated efforts of Assembly’s management to make financial offers.

37 “Ogden Boys Win from Assembly,” Morning Examiner, May 8, 1905: 8.

38 Maurice L. Howe, “Jack Greenwell, Personal Pioneer History: Interview,” Federal Writers Project, Utah State Historical Society Collections, July 12, 1939: 3.

39 “With the Sports,” Daily Utah State Journal, May 6, 1905: 6.

40 “Colored Men Win,” Salt Lake Herald, August 4, 1906: 8.

41 “Baseball at Ogden,” Salt Lake Herald, July 1, 1907: 7.

42 “Occidentals Return,” Salt Lake Telegram, May 10, 1909: 7.

43 Salt Lake City’s Richelieu Club and the Americus Club.

44 According to 1900 Census numbers, 336 Blacks resided in Salt Lake County compared with 51 in Weber County.

45 Ryan Whirty, “The Salt Lake Occidentals, Conclusion,” The Negro Leagues Up Close, December 17, 2015, https://homeplatedontmove.wordpress.com/2015/12/20/the-salt-lake-occidentals-the-conclusion/

46 Jeffrey Nichols, “The Boss of White Slaves: R. Bruce Johnson and African American Political Power in Utah at the Turn of the Twentieth Century.” Utah Historical Quarterly, Volume 744, Number 4, 2006. https://issuu.com/utah10/docs/uhq_volume74_2006_number4/s/10191716