Bill Davidson vs. the Barker-Karpis Gang

This article was written by Scott M. Johnson

On April 4, 1933, the morning sun shone across the streets of downtown Fairbury, Nebraska. It was Election Day with a new mayor to be announced, and the local Ministerial Association was haughtily (and successfully) lobbying city authorities to ban Sunday showings in local movie theaters. Insurance man Homer Yeakle had his daughter, Gwen, and stepdaughter, Wilma, in tow. Both were about 19 years old and itching to spend their Tuesday doing some shopping. Their first stop was the First National Bank: Homer needed to reload his wallet for his daughters’ spending spree.

Just then, a large, black 1932 Buick careened to a halt at the curb, and four men hustled out. As Homer and the girls ambled toward the bank, the fast-stepping foursome were suddenly striding beside them. One of the men, carrying a briefcase, courteously held the door for the Yeakles. Then they were shoved abruptly and roughly inside, and the four men burst in behind them. A cry reverberated off the stone walls of the lobby.

“This is a holdup!”

Pistols and submachine guns were pulled, and a few warning shots fired. The lobby full of customers let out a collective gasp. A bank employee jerked back in shock and swallowed his chaw.1

The Barker-Karpis Gang, running neck-and-neck with Bonnie and Clyde in the bank-robbing pennant race, had come to pay a call on Fairbury.

Employees and customers were immediately ordered to lie face-down on the floor. One fellow who was slow in responding was cracked from behind with a gun butt. The cashier in charge was commanded at gunpoint to open the vault. Henchman Earl Christman was pacing around twitchily, waving his machine gun back and forth and saying over and over, “Shouldn’t I let them have it?” The figures on the floor held their breath.

As soon as the vault was opened, a cash drawer was emptied of $25,650. A nearby packet of $22,000 was overlooked in the excitement. Frank Nash was the leader of this heist, a cool customer and well-versed in the business of bank robbery. He shouted, “Where’s the bonds? Hurry up and get those bonds!” This was the big payoff, $125,000 in bonds that were hastily thrust into a dirty flour sack along with the cash. They’d gotten what they came for, and the gunmen headed for the exit.

Scant moments had passed since the gangsters had burst into the bank lobby, but word was quickly spreading and an anxious phone call from a nearby merchant had been picked up in the Jefferson County Courthouse, right across the street.

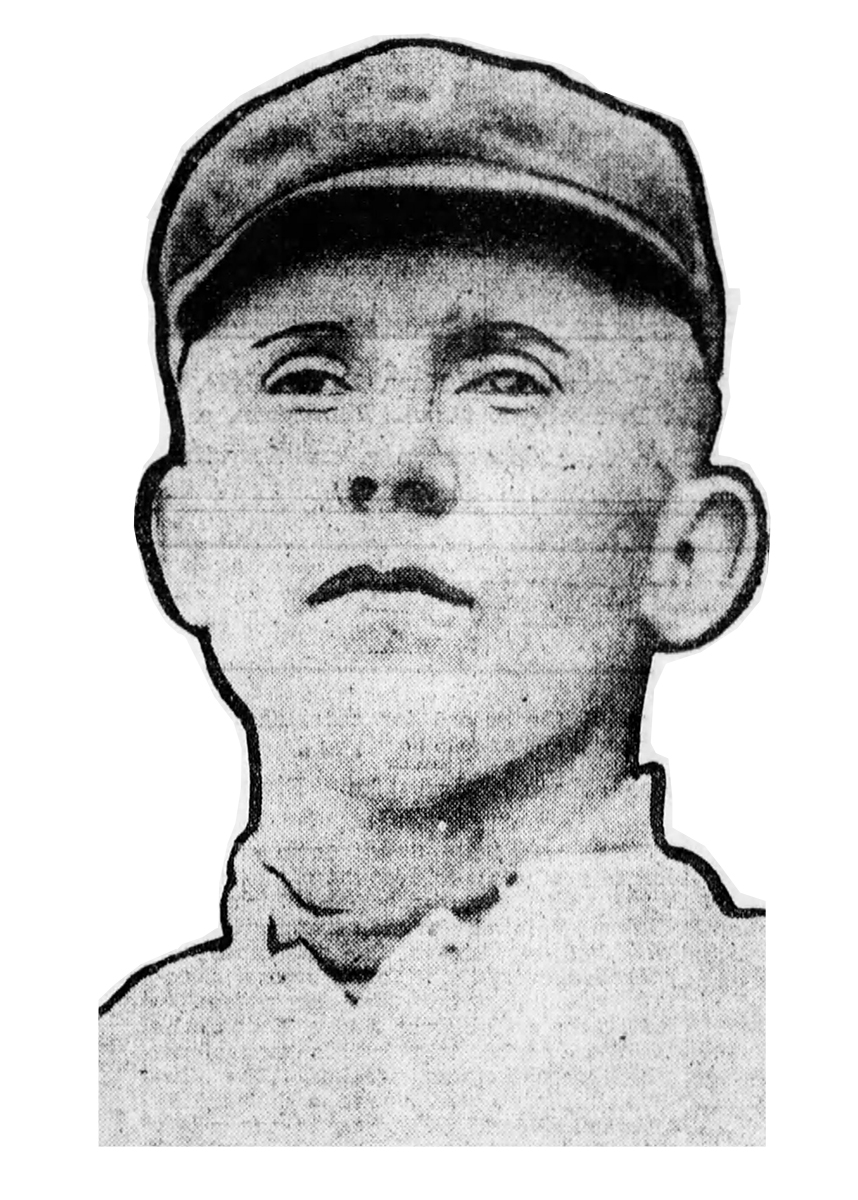

The responder was Deputy Sheriff Bill “Davy” Davidson. Then aged 48, Davidson was a former insurance man, billiard-hall manager, traveling candy salesman – and, 20-some years earlier, a major-league outfielder. Quite fortuitously, he had picked this very day to discuss with Glenn Johnson, a Des Moines gun salesman, the need for upgraded firearms for the Sheriff’s Office. Johnson had been showing off a few new models. The two experienced shooters picked up a pair of rifles and hurried to the street.

The responder was Deputy Sheriff Bill “Davy” Davidson. Then aged 48, Davidson was a former insurance man, billiard-hall manager, traveling candy salesman – and, 20-some years earlier, a major-league outfielder. Quite fortuitously, he had picked this very day to discuss with Glenn Johnson, a Des Moines gun salesman, the need for upgraded firearms for the Sheriff’s Office. Johnson had been showing off a few new models. The two experienced shooters picked up a pair of rifles and hurried to the street.

The second they stepped outside and squinted into the sun, they found themselves in a gunfight with the Barker-Karpis Gang. Two gangsters standing watch outside the bank opened fire, as well as a third waiting inside the Buick. As another hustled out of the bank into the firestorm, he wrapped his arm around a terrified bystander; dragging her along as a shield, he rushed to the car and forced her in with him, shooting the entire way. There was a shriek as Homer Yeakle’s stepdaughter was roughly yanked from the lobby floor; she too was hauled out as the human shield for another gang member. Two other men, employees of the bank, were shoved out as shields for the final gunmen; one was made to stand at the car’s front and the other, Keith Sexton, at the car’s rear, where he stared vulnerably into the rifles of Davidson and Johnson, who dared not fire at the getaway car lest they hit him.

As gunshots popped, Johnson took a bullet in the shoulder and rolled to safety under a parked car. Davidson took a hit in the ankle and sheltered behind another auto, quickly tying a handkerchief around the wound. He then took a stance with his rifle, carefully re-aimed at a figure wielding a submachine gun, and nailed him before he could reach the getaway car. As the gangster twisted to the ground, his finger clutched the trigger, and the machine gun fired in a sweeping, circular motion, first perforating the unfortunate hostage Sexton five times. The rest of his shots fanned out in all directions before he hit the pavement and was hastily dragged by his mates into the car.

Glass exploded all around the nearby businesses. “Plate glass windows and the nerves of store employees and customers in the vicinity of the bank were well shot up,” reported the Fairbury News. In the Spear-Buswell Drug Store, the front window was blasted out, and several shots tore up a basket of Gillen & Bonny candy bars and the plate-glass mirror behind the soda fountain. At the Fairbury Electric Shoe Shop, an employee collapsed to the floor when a bullet struck a dust mop next to her, toppling an aluminum kettle to the floor.2 County Attorney Art Denney sought shelter behind a tree, “which he declared felt entirely too small to avoid being hit by the bullets. Knowing Art, and having seen the size of the tree, Fairburians agree with him regarding its value as a shield.”3

With the whole Barker-Karpis Gang and two hostages on board, the Buick roared off, one of the gangsters casting giant tacks in its wake to derail any pursuers. Two miles out of town, they pulled over where an eighth man had been waiting. Several members of the gang jumped into the second car, and they burned rubber for Kansas City. The two hostages, released and unscathed and flushed with excitement, watched them disappear into the distant dust; they flagged down a ride back to town, where they recounted their thrilling adventure, enough to last a lifetime.

It had all happened so fast (and this was long before the advent of surveillance cameras) that it was years before the robbers were even identified:4

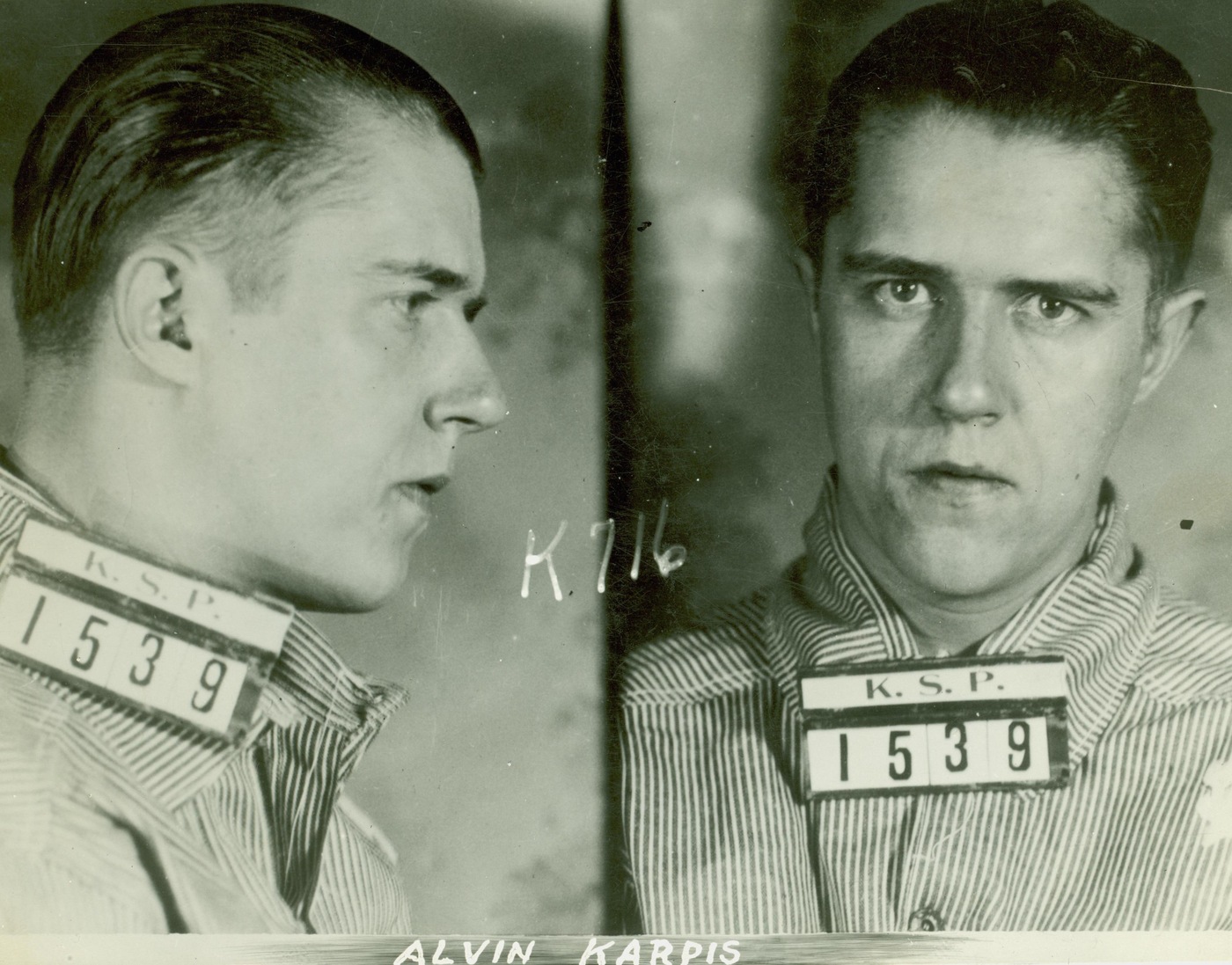

- Alvin “Creepy” Karpis – the leader of the Barker-Karpis Gang and the only “Public Enemy Number One” who was ever taken alive. He served sentences at Alcatraz and McNeil Island Penitentiaries (where he met Charles Manson and coached him in playing guitar).

- Fred Barker – died with his mother, Kate “Ma” Barker, in a 1935 FBI Chicago raid.

- Arthur “Doc” Barker – imprisoned in Alcatraz and shot in an escape attempt.

- Frank Nash – the country’s most feared bank robber, killed just two months later by Pretty Boy Floyd in the legendary Kansas City Union Station Massacre, June 17, 1933.

- Volney Davis – imprisoned in Alcatraz for the kidnapping of banker Edward Bremer.

- Edward Green – fatally shot by federal agents in Minneapolis, April 11, 1934.

- Jess Doyle – the second getaway driver, spent a decade in the Nebraska State Penitentiary.

- Earl Christman – felled by the bullet from Davy Davidson’s rifle, he succumbed at the home of a Kansas City mobster and was buried in a shallow grave behind the house.

Amazingly, with all the gunplay on April 4, Christman was the only fatality. The unfortunate hostage Keith Sexton recovered fully in short order. So did the gun dealer Johnson, who called it a profitable day when the town immediately upgraded the sheriff’s arsenal.

Davy Davidson’s recovery was especially glowing. All his years in baseball had never seen anything like this kind of excitement or this kind of reward. When the weekly Fairbury Journal came out a few days later, he emerged as a paragon of gallantry, a man among men. As every soul in town related their own version of the thrilling robbery of the First National Bank, Davidson was the indisputable hero of every tale. However, any thoughts he had about the eventful Tuesday appear to have been kept to himself. When he later appeared in local papers, after his ankle had healed, it was back to business as usual, keeping the peace in Fairbury. True to the tradition of classic Western heroes, he let his actions do his talking.

Acknowledgments

This story was reviewed by Rory Costello and Len Levin, and fact-checked by Tim Herlich.

Photo credits: Alvin Karpis, courtesy of FBI.gov. Bill Davidson, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 5, 1911.

Sources

A wealth of detail about this thrilling Fairbury morning can be found in the pages of the Fairbury News, April 6, 1933; the Beatrice (Nebraska) Daily Sun, April 4, 1933: 1-2; and a retrospective article, “The Day the Barker Gang Hit Fairbury,” Sunday Omaha World-Herald Magazine of the Midlands, March 30, 1969: 6-8.

This narrative has been constructed without any details fictionalized.

Notes

1 Per “The Day the Barker Gang Hit Fairbury”: “Bank employee F.P. Conrad was so frightened he swallowed his chewing tobacco.”

2 Electric shoe shops were a new thing, merchants who had electric machinery for repairing shoes.

3 “More About the First National Bank Robbery,” Fairbury (Nebraska) News and Gazette, April 6, 1933: 2.

4 “Robbery Most Exciting Event in History of First National Bank,” Fairbury Journal, October 8, 1953: 20. A report sent to officials at the First National Bank by the FBI detailed the participants and their later fates. Little was known about the gang that pulled off the 1933 heist until this article appeared.