Logan Squares

This article was written by Brian McKenna

In the midst of a successful career in the major leagues, Jim “Nixey” Callahan quit the Chicago White Sox after the 1905 season, pinning his fortunes on a plan to establish a semipro club in Chicago. He first purchased the rights to an old amateur playing field in Logan Square, a section of Chicago. Then he built a grandstand, refurbished the grounds, and enclosed the area with a fence so he could charge admission. Next, Callahan needed some competition. It took a lot of finagling and appeasing but he emerged from the winter with one of ten teams in a new city league. In order to separate his club from the pack, Callahan sought the best possible talent to fill his roster.

In the midst of a successful career in the major leagues, Jim “Nixey” Callahan quit the Chicago White Sox after the 1905 season, pinning his fortunes on a plan to establish a semipro club in Chicago. He first purchased the rights to an old amateur playing field in Logan Square, a section of Chicago. Then he built a grandstand, refurbished the grounds, and enclosed the area with a fence so he could charge admission. Next, Callahan needed some competition. It took a lot of finagling and appeasing but he emerged from the winter with one of ten teams in a new city league. In order to separate his club from the pack, Callahan sought the best possible talent to fill his roster.

Therein lies the crux of the story of the Logan Squares. Callahan ignored organized baseball’s proclaimed rights to individual players. He signed whoever was available, regardless of their status with another club. On the field, this proved a success; at the end of its first season, the Logan Squares defeated both the local White Sox and Cubs, both fresh from competing in the 1906 World Series. The victories made national headlines for the semipro squad. Callahan even went to court to air grievances against baseball’s ruling body, the National Commission, and called for an investigation of the major leagues as a monopoly. The feud sparked several contentious years between organized baseball and Callahan.

Callahan didn’t actually raid major-league clubs, but he wasn’t above fielding men who were suspended or otherwise available. Some of the names who played with and against the Logan Squares were among the tops in the business. For this, Callahan became known as the “Anarchist of Baseball,” at least by major-league officials. The National Commission established a rule in 1908 in response to Callahan’s encroachment. It clearly defined the penalties for any organized-baseball player who played with or against the Logan Squares or any other outlaw club. A couple of years later, after the Logan Squares’ fan base started to diminish, Callahan rejoined the majors. Comiskey and American League president Ban Johnson (a member of the National Commission) welcomed Callahan back with a meager fine; they were pleased to see an end to the embarrassing struggle with a mere semipro squad.

James Joseph Callahan, a 19-year-old semipro player – Nixey was a childhood nickname – was recruited by Philadelphia Phillies manager Art Irwin to join the club in 1894. After a nine-game tryout with the Phillies, Callahan spent most of the next three seasons in the minors. In 1897 he established himself as a full-time National Leaguer, both as a pitcher and utility player for the Chicago Colts. Over the next four seasons, he won 65 games. Chicago’s other mound ace, Clark Griffith, was a leading instigator of the player uprising at the turn of the century that ultimately stocked the new American League with major-league-quality talent. Both Callahan and Griffith joined Charles Comiskey’s crosstown White Sox, with Griffith assuming the field manager duties. When Griffith left to take over the relocated Baltimore Orioles in New York City, Callahan was named Chicago’s manager. Though he relinquished the title in the middle of 1904, he remained with the club. At the age of 31, in November 1905, he announced his retirement from the White Sox despite still being a productive player.

Callahan left the American League to open a business, his own baseball club. It was a blow to both the White Sox and the major leagues. Callahan was a valued commodity; The Washington Post wrote in November 1905: “Callahan is considered one of the greatest all-around players of the game today.” Chicago has always been one of the most solid baseball cities; at the onset of the 20th century, not only did the city support two major-league clubs, but fans filled seats for hundreds of local amateur and semipro clubs. Many of the teams joined associations that handled their booking, set, their schedules and guaranteed a venue on the busy weekends. One of these, the Amateur Managers’ Baseball League, was formed in 1901, and by the following year, it comprised more than 150 clubs and was still growing. By the end of 1906, the Chicago Intercity Association included nearly 400 clubs. The number rose to 550 by 1909. In particular, there were a couple of dozen solid semipro clubs dotting the local map. Callahan saw the potential for financial success by owning one of them. As Baseball Magazine noted, “He is bright and brainy, and a hustler. No one has a larger personal following.” Callahan surely noticed his peers cashing in on team ownership. Even Griffith had found some success sponsoring a semipro squad in 1901 and ’02. Numerous other colleagues dove into club ownership ranging from semipro to the majors. Callahan found his opportunity after the 1905 season.

In November of that year, Callahan purchased the rights to the ball grounds at Logan Square, a community about five miles northwest of Chicago’s Loop. Milwaukee Avenue, one of Chicago’s main thoroughfares, bisected the community. The area had been heavily populated by immigrants. At first an independent community, Logan Square was, in increments, annexed by the city of Chicago between the 1860s and 1880s. The area’s population grew dramatically after the Fire of 1871. Since it lay outside the city’s fire limits, cheaper homes could be built in Logan Square that attracted those who lived closer to the heart of the city. The rapid-transit system connected Logan Square to the rest of the city in 1890, an event that further spurred the building of new homes, paved streets, and an impressive planted boulevard system.

The ballpark was at the corner of Diversey and Milwaukee Avenues. Organized games had been played there at least as early as 1895, perhaps a lot earlier. Callahan’s first order of business was to enclose the ball grounds and build a respectable grandstand. On February 22, 1906, work began on the grandstand after a fence was erected enclosing the grounds. Secondly, Callahan needed to set a schedule and build his roster. After a great deal of cajoling, he helped found the ten-team Chicago City League. Besides the league schedule, the club would also play college and amateur nines, other local semipro squads, and traveling independent clubs, some of which were African-American squads. Professional teams would also be engaged when possible. The games were played for the most part on weekends. The Chicago City League became a model for urban competition throughout the country, especially after the Logan Squares defeated both World Series teams at the end of the year.

The first official game took place at the revamped Logan Square field on April 15, 1906. Callahan pitched an 11-4, complete game victory over the Kenosha club. Chicago legend Cap Anson served as the umpire. From the start, problems arose with organized baseball. When Callahan didn’t report to the White Sox, he was automatically placed on the ineligible list. After all, he was bound by organized baseball’s reserve clause. On a personal level, Callahan remained on friendly terms with Charles Comiskey. The White Sox owner, needing an outfielder, even offered Callahan an open contract allowing him to play for both clubs. He would join the White Sox for contests that didn’t interfere with his Logan Squares commitment. The two came to terms verbally at the end of August. Callahan hopped a train to Detroit to join the White Sox but was turned away when he arrived, supposedly on the orders of American League president Ban Johnson.

Callahan’s Logan Squares were a financial success in 1906. He loudly proclaimed that he had earned $12,000 from his team, an amount far exceeding his previous year’s earnings in the majors. It wasn’t unusual for crowds to number in the thousands, sometimes more than 5,000. Things kicked into high gear after the major-league season ended. On Saturday, October 20, Callahan pitched the Logan Squares to a 2-1 victory over the newly crowned world champion Chicago White Sox in front of 5,000 fans at Logan Squares Park. Nick Altrock was on the mound for Comiskey’s nine. The following day, Tom Hughes, the Washington Nationals’ hurler, pitched the Logan Squares to a 1-0 victory over Three-Finger Brown and the National League champion Chicago Cubs. Brown threw a wild pitch in the tenth inning that allowed the game’s only run to score. Callahan knocked two of the four hits off Brown. After the game, the crowd stormed the field. In all the excitement, Callahan and Hughes, both disheveled and with torn jerseys, barely made it out alive; a police escort had to rush them to safety. The attendance, 8,000, may have been the largest ever for a semipro squad in Chicago. The White Sox’ and Cubs’ lineups for the games weren’t exactly all-star squads, though there were quite a few regulars, but that hardly mattered; the Logan Squares were instantly dubbed the finest semipro team in the country. Noting Callahan’s success, Cap Anson formed a team within a week with Mont Tennes, a Chicago gambling figure who later surfaced in the aftermath of the Black Sox affair. Jimmy Ryan, a longtime member of the Cubs who was now out of the major leagues, also owned a team in the Chicago City League. Organized-baseball officials on the other hand weren’t as enthusiastic. They referred to Callahan as the “Anarchist of Baseball.”

At dispute was Callahan’s use of players under contract to teams in organized baseball. On September 10, 1906, Lou Fiene of the White Sox was fined by the National Commission for pitching for the Logan Squares a week earlier. Hughes had recently joined the Logan Squares after being suspended at the end of the season by Washington manager Jake Stahl for excessive drinking. In 1906 Callahan also fielded Vive Lindaman of the Boston Beaneaters and a few others playing under aliases. As a magnate, Callahan made a particular effort to intercede on behalf of these players with organized baseball, to help them reestablish their status. For example, he negotiated for the readmission of Hughes with the National Commission, which let Hughes back in with a $100 fine the following March.

Provoking organized-baseball even more, Callahan filed a $3,000 lawsuit against the White Sox for breach of contract on November 3, 1906, a day after the National Commission fined Lindaman $100 for playing with the Logan Squares. Callahan sued White Sox owner Comiskey only for reasons of jurisdiction; the object of Callahan’s wrath was the National Commission, particularly Ban Johnson. Callahan’s attorney asked for a review of the National Commission as a monopoly, exclaiming, “The defendant belongs to one of the greatest trusts ever conceived,” one far superior in his opinion to the Standard Oil Company. Callahan asserted that he was given a contract on March 1 by Comiskey but was not given a roster spot. He was turned away on Johnson’s orders when he joined the White Sox in Detroit on August 30. He wanted six weeks of pay and a World Series share. Callahan demanded damages because of Johnson’s refusal to reinstate him. Callahan and Johnson traded barbs in the press for weeks. It was later learned that Johnson never put the request for reinstatement to a vote by the National Commission; he and secretly tabled it.

Johnson denied all the charges, asserting that Callahan had no case and wasn’t even in shape to fulfill his contract. Then Johnson plunged into the crux of his gripes: He was irate that Callahan utilized men under contract to organized baseball, whether on the ineligible list or not. Moose McCormick, the property of the Phillies, played under the name of Harrison for the Logan Squares. Gus Dundon of the White Sox used the name Casey and Lindaman went by Evans. Johnson said Happy Townsend, who was suspended for drunkenness by the Cleveland Naps, had been offered $50 a week by the Logan Squares. Johnson also accused Callahan of coaxing Ed McFarland to jump the White Sox. Still, the American League president said he was willing to forget the transgressions and offer Callahan his reinstatement under certain conditions. For his part, Callahan argued that he was being persecuted by Johnson and the baseball monopoly for merely running his business. Defending his actions, he said he hadn’t done anything remotely as shocking to the structure of organized baseball as Johnson and American League owners undertook in early 1901. In fact, Callahan alleged that Johnson had asked him to do much worse during the war between the American and National Leagues between 1900 and 1902. On November 15, the National Commission reinstated Callahan provided he agree to drop the lawsuit and dispose of his club. All knew he wouldn’t. In the end, Callahan’s suit never was argued in court.

In January 1907, the National Commission levied $50 fines on each player of the Peoria club of the Three-I League who played against the Logan Squares the previous fall. That same month, Callahan and Lou Criger, a catcher with the Boston Americans, began coaching the Notre Dame University baseball squad. The big preseason news, though, was Callahan’s signing of Mike Donlin of the New York Giants and Jake Stahl of Washington for the Logan Squares. After holding out from the Giants for all of 1906, Donlin joined the semipro squad in April. 1907. Callahan first had to gain a waiver from the local Artesian club, with whom Donlin had already signed. Stahl was also engaged in a dispute with his Washington club. Donlin and Stahl played for the Logan Squares in 1907, then were fined $100 and reinstated by organized baseball in 1908. The Giants, to smooth the way for Donlin’s readmittance, falsely claimed that they gave him permission to play for the Logan Squares. Callahan also tried to sign the New York Highlanders’ Hal Chase in early 1907, but was blocked by Clark Griffith, the Highlanders’ manager.

The Logan Squares’ profits and Callahan’s connections allowed him to seek some of the top talent in the country, professional or otherwise. It perhaps established the Logan Squares in a special category hovering between semipro and professional, like many of the black clubs of the pre-Negro Leagues era. Besides those already mentioned, others Callahan signed included Artie Bell, Al Demaree, Gus Dundon, Frank Erickson (minor-league catcher), Lou Fiene, Hub Hart, Ed Hughes, Burt Keeley, Louis Lippert (longtime minor-league outfielder), Moose McCormick, Ed McFarland, Bill McGill, Frank McNichols (minor-league third baseman), Dutch Meier, Bob Meinke, Charles Reading (minor-league catcher), Percy Skillen (Dartmouth pitcher and captain), Jack Thiery (longtime minor-league player and manager), and Jimmy Wiggs (minor-league pitcher).

Some of the top competition in Chicago was the black clubs, such as the Leland Giants and St. Paul Gophers. Rube Foster’s Leland Giants rivaled the Logan Squares as the top semipro club in the area. One particularly hard-fought game between the two clubs took place on July 20, 1907. Foster pitched 13 innings to defeat Tom Hughes and Lindaman, 5-4. The Chicago Tribune was particularly impressed with Giants second baseman Nate Harris, who flawlessly handled 13 chances, many of them difficult. The Leland Giants defeated the Logan Squares eight out of nine games in 1908.

On October 13, 1907, the Logan Squares defeated a squad of White Sox, 4-1. Nick Altrock and Frank Owen pitched for Chicago and Walter Most went to the mound for the Logans in the postseason matchup. Six days later, the Logan Squares fought the American League champion Detroit Tigers to a 10-inning, 8-8 tie at Logan Squares Park. The Logans tied the game with seven runs in the ninth inning. Al Demaree pitched for Callahan against Ed Killian. Donlin manned first base and Callahan played left field. The Tigers featured Ty Cobb, Sam Crawford, Germany Schaefer and Bobby Lowe. The next day, Cy Falkenberg pf the Washington Senators pitched the Tigers to a 4-0 victory.

In December, Callahan negotiated to purchase the St. Paul club of the American Association and move them to Chicago. Cubs owner Charles Murphy and the National Commission objected strongly, and the plan fell through. (The idea was raised again at the end of 1909 with Johnny Kling of the Cubs leading the charge.) As the Fort Wayne News summed it up, “No man is more talked of in baseball than Jimmy Callahan, manager of the famous Logan Squares of Chicago. Callahan is a thorn in the side of the National Commission.”

In March 1908, Ty Cobb of the Detroit Tigers, baseball’s newest and brightest star, and Tommy Leach of the Pittsburgh Pirates shocked the baseball establishment when they wrote to Callahan inquiring of the possibility of joining the Logan Squares. The baseball press was also stirred: The Washington Post headlined an article, “Callahan Wants Too Much in Baseball.” Actually, Cobb and Leach were using Callahan’s club as a bargaining chip in contract negations with their own clubs. Cobb had already rejected an offer by Tigers owner Frank Navin; he wanted a three-year deal at $5,000 a year. Germany Schaefer of the Tigers was actually the first to use the Logan Squares as a tactic in negotiations, back in January 1906.

Callahan accompanied the Washington Senators and Minneapolis Millers to spring training in Texas in March. The two clubs were run by the Cantillon brothers, the Senators by Joe and the Millers by Mike. Callahan played a few games with the Millers. On March 27, National Commission chairman Garry Herrmann sent Mike Cantillon a telegram ordering him not to play Callahan again, since he was on the ineligible list. In truth, there were no formal rules at the time to cover the situation, but the National Commission acted quickly to close the loophole. Joe Cantillon was also interested in signing his good friend Callahan for the Senators but backed off rather than antagonize Ban Johnson and Herrmann. Cantillon, though, did make a move that irked Johnson. He paid Callahan for pitcher Burt Keeley, who was otherwise a bank clerk in Chicago making $25 a week. Callahan had signed him in early 1908 to play on weekends for $35 a week. The purchase upset Johnson because the major leagues did not recognize the contracts of semipro clubs; thus, if Cantillon wanted a player, he had merely to raid Callahan’s roster. Callahan also acted as a de facto agent for Comiskey, Griffith, and others in organized baseball, signing talent for their clubs. Johnson put an end to that as well.

In April 1908, Callahan applied to the National Commission for reinstatement. Around the same time. Ed Hughes, Long Tom Hughes’ brother and the property of the Boston Americans, was sent to Little Rock but he refused to report. Instead, he signed with the Logan Squares. Hub Hart of the White Sox also inked a deal with Callahan. On May 6, the major leagues adopted a rule barring players from appearing in games in which either team had ineligible players, managers or owners, and setting fines of at least $200 for violations. Callahan was one of the chief targets of the rule. Then, on June 2, Callahan was formally denied reinstatement by the National Commission. In October, Comiskey gave Callahan his unconditional release in order to pave way for his reinstatement by baseball’s ruling body.

As usual, major- and minor-league players barnstormed after the season in 1908 to supplement their income. In violation of the new rule, the Washington Senators, Chicago White Sox, Minneapolis Millers, and a smattering of other minor-league players took the field against the Logan Squares at their park. The Millers players did so in defiance, openly declaring their intentions loudly beforehand. On October 10, Walter Johnson pitched against the Logans, defeating Ed Hughes, 11-2. Five of the Logan Squares that day were on organized baseball’s ineligible list: Callahan, Dutch Meier, Frank McNichols, Hughes, and Victor Haisman. On October 17, the National Commission fined the major and minor leaguers involved $200 each and placed them on its ineligible list as well. (The directive was rumored to be retaliation by Ban Johnson for a bar fight at Joe Cantillon’s saloon in Chicago on October 12 after the third game of the World Series. The Washington Post said Callahan “whaled the tar out of Ban Johnson.”) In addition to its action against the players, the commission orders the Tigers and White Sox not to play games they had scheduled with the Logan Squares. The White Sox ignored the threat, playing the Logan Squares on October 17 and 18. The Tigers backed off.

Players declared ineligible by the National Commission were Ed Hughes of the Boston Americans; Jim Delahanty, Jerry Freeman, Walter Johnson, Mike Kahoe, Burt Keeley, George McBride, Bill Shipke, and Jesse Tannehill of Washington; and Nick Altrock, Jake Atz, Jiggs Donahue, Lou Fiene, Hub Hart, Frank Owens, Billy Purtell, Frank Roth, Frank Smith, and Doc White of the White Sox. Minneapolis and Milwaukee American Association players declared ineligible were Bill O’Neill, Rabbit Robinson, Wheeler, Kerwin, Tom Dougherty, Tony Smith, Boileryard Clarke, Fred Olmstead, Hecklinger (first name unknown), and Bruno Block. A few others were also declared ineligible from other minor-league clubs. Callahan interceded on the accused players’ behalf in meetings with Harry Pulliam and Garry Herrmann, trying to get them reinstated. Eventually the fines were lowered to $50 for each. The players began paying in January,and all were reinstated before the next season began. (Six years later, Ban Johnson returned Walter Johnson’s $50 fine out of respect for one of the league’s top drawing cards).

With all the publicity he had accrued over the last few years, Callahan branched out in 1909. He promoted foot races, flooded Logan Square Park for ice skating, managed heavyweight boxing champion James J. Jeffries’ United States tour. He also began a career on stage, acting in plays and touring the vaudeville circuit telling baseball stories. He continued on stage for several years.

In February 1909, Callahan suggested that major-league baseball enter into a working agreement with his club. Ban Johnson objected, but the major leagues formally recognized player contracts with semipro clubs in July. Earlier, on March 26, had been Callahan was reinstated by the National Commission, suffering only a $100 fine. But he decided to stay with the Logan Squares, and in May he turned down offers from Joe Cantillon, then managing the Senators and Clark Griffith, managing the Reds.

Callahan’s belief in the strong future of semipro baseball in Chicago back in 1906 proved prophetic in September 1909. More than 1,000 games took place each day in and around the city on the first weekend of the month. Attendance for the two days was estimated at a half-million. On September 7, Johnny Kling ran afoul of the National Commission when he brought his Kansas City club to Chicago to face the Logan Squares in a doubleheader. Kling played in both games. The Cubs later asserted that he had been permitted to do so to help ease his admission back into the majors. Meanwhile, Callahan and Kling hatched unfulfilled plans to organize a new league. In November, just to prove that all was not sweetness and light, Callahan was engaged in a dispute involving the rights to a minor-league pitcher, Bill Torrey. The dispute pitted the Logan Squares against Springfield of the Three-I League, the New York Giants, and the Cincinnati Reds. It surprised few when the National Commission chairman – and Reds’ president – Garry Herrmann awarded the player to Cincinnati.

Attendance began to wane for the Logan Squares in 1910, the season Comiskey Park opened. On August 27, the Logan Squares and Rogers Park clubs played a night game at the park, using a temporary electrical lighting system. The Logan Squares won, 3-1, with 3,500 in attendance. Callahan played center field and drove in two runs. On October 31, the Cubs defeated the Logan Squares, 3-1. For the year in the City League, Callahan played 29 games and batted .333, going 29-for-87. He led the league in stolen bases with 38, twice as many as his nearest competitor. The Logan Squares as a whole batted .236.

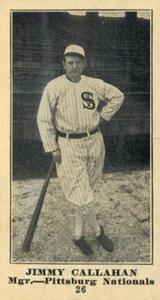

Over the winter of 1910-11, Comiskey asked Callahan, with his promotional skills, to assume the presidency of the White Sox. Callahan, still wanting to play, talked Comiskey into signing him as an outfielder. He signed a contract as a player-manager on February 17, 1911, and played two full seasons, hitting .281 in 1911 and .272 in 1912. He retired as a player after appearing in nine games in 1913. Callahan spent 1915 in the White Sox front office, then managed the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1916 and 1917. He died in Boston in 1934.

As for the Logan Squares, when Callahan rejoined the White Sox, he disbanded the semipro team and tore down the fence around the park, returning the field to the amateurs. The team name was later revived by semipro and professional squads. Ossie Bluege, Phil Douglas, Johnny Rigney, Hippo Vaughn, and Buck Weaver all played for subsequent versions of the Logan Squares.

Sources

Baseball Magazine

Chicago Record-Herald

Chicago Tribune

Decatur Herald, Illinois

Elmira Reporter, Ohio

Encyclopedia,chicagohistory.org

Lebanon Daily News, Pennsylvania

Newark Advocate, Ohio

New York Times

Oakland Tribune

San Antonio Light and Gazette

Sandusky Star Journal, Ohio

Sporting Life

Washington Post