April 11, 1907: Reds celebrate a ‘grand’ Opening Day with win over Pirates

By 1907, Opening Day was one of the grand sporting and social events of the year in Cincinnati. It was a festival of music and parades, a day of noisy fun and high fashion, an occasion to skip school or knock off business and go to the ballpark, where the cream of Cincinnati society and the elite of local politics were sure to be conspicuously mingling.

By 1907, Opening Day was one of the grand sporting and social events of the year in Cincinnati. It was a festival of music and parades, a day of noisy fun and high fashion, an occasion to skip school or knock off business and go to the ballpark, where the cream of Cincinnati society and the elite of local politics were sure to be conspicuously mingling.

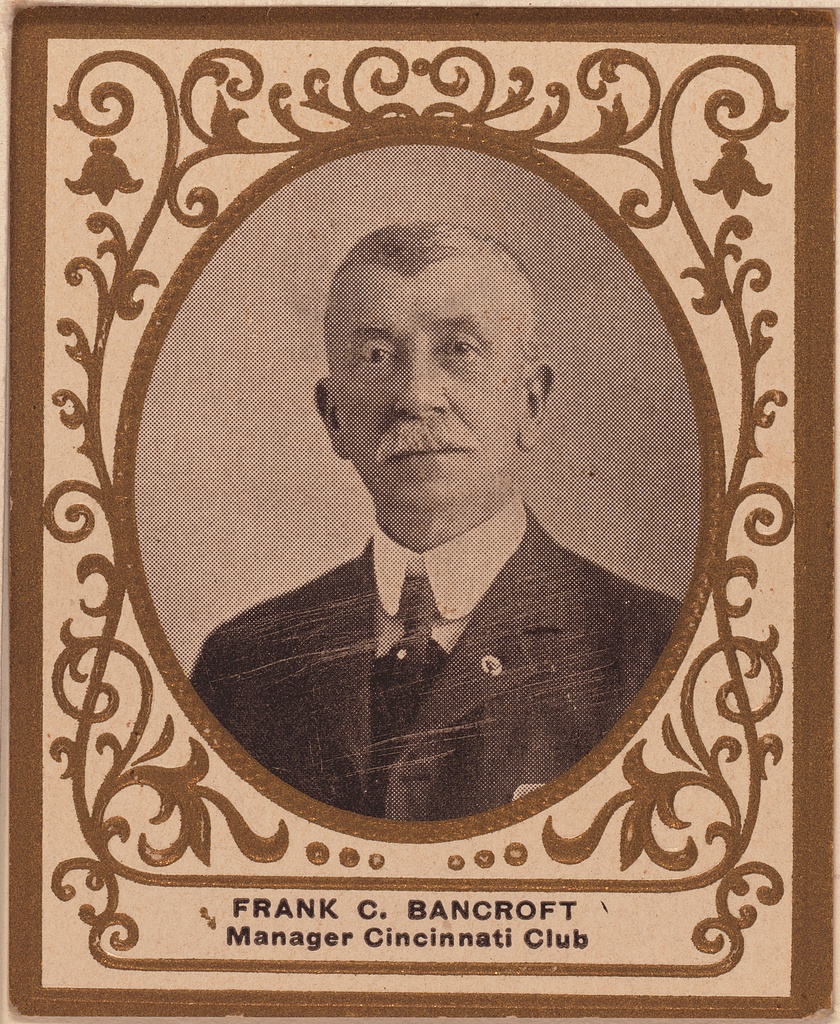

The man most responsible for this unique celebration of the national pastime was Frank Bancroft, the Reds’ longtime business manager. Bancroft had at various times trained in the circus business, managed minstrel troupes, run an opera house, and owned a hotel and a roller-skating rink. He had been involved in baseball, in the words of Alfred H. Spink, founder of The Sporting News, “ever since it was worth talking about.”1 He organized his first baseball club in 1877 and managed the Providence Grays to a National League pennant in 1884. Bancroft took the first team of American barnstormers to Cuba in 1879 and was credited with staging baseball’s first home-plate wedding in 1893.

He also effectively invented Opening Day. Bancroft organized, promoted and encouraged all sorts of festivities that gave the day a flavor all its own. The pattern had been set by the mid-1890s with the introduction of the trolley parade through downtown and the pre-game band concert at the ballpark. In 1907 some of the most avid rooters formed “tallyho parties,” arriving in large open-air carriages. The Cincinnati Commercial Tribune doubted that any city had ever before seen such a gathering of tallyhos for a baseball game. The largest were drawn by as many as six horses and could carry 40 people. The Cincinnati Enquirer added that many were decorated with large banners and their occupants decked out “in all sorts of absurd costumes.”2

The side the Reds sent out to inaugurate the season was made up mostly of newcomers. The only returning regulars in the lineup were pitcher Bob Ewing, second baseman Miller Huggins, and catcher George “Admiral” Schlei. Center fielder Alphonzo “Lefty” Davis and first baseman John Ganzel were on the elderly side of 30 and returning to the big show from the minor leagues. Three others were making their major-league debuts: Outfielders Mike Mitchell and Art Kruger, and third baseman Johnny Kane were all recruits from the Pacific Coast League. Twenty-two-year-old Mike Mowrey was playing his 29th game in the major leagues, but only his second at shortstop.

Pittsburgh, by contrast, had an experienced and formidable team led by player-manager Fred Clarke, third baseman Tommy Leach and shortstop Honus Wagner, widely regarded as the greatest player in the National League. Counting pitcher Deacon Phillippe, four of the Pirates’ starters had been together since 1901. They had won three pennants and averaged 93 victories a season.3

The Reds had won only one of their previous eight openers. Among the defeats was a 7-1 embarrassment in 1903, when Phillippe pitched a two-hitter. The omens were not promising for Cincinnati. Ewing hadn’t worked a complete game in spring training and there was some question whether he was ready to go nine innings. Known as a hot-weather pitcher, he was rarely at his best amid the April showers and intermittent cold snaps of springtime in Ohio.

The day did not dawn auspiciously. A scheduled exhibition with the Chicago White Sox had been canceled the day before for fear the players would catch pneumonia. Early-morning temperatures on Opening Day were barely above freezing. Reds officials had hoped for a turnout approaching 20,000, but had to settle for half that. Gamblers were offering odds of 3-to-1 and even 4-to-1 against the home team.4 The Reds gave away one run on Schlei’s throwing error in the second inning and another when Ewing issued a bases-loaded walk in the third. Phillippe, meanwhile, escaped a couple of ticklish situations and held the Reds scoreless through five.

The temperature had risen into the mid-40s by game time and the bundled-up crowd made up in enthusiasm what it lacked in numbers. A band played between innings and the rooters kept up a racket with bells, whistles, bugles, and “every conceivable instrument to make noise,”5 the Commercial Tribune reported. The decibel level reached new heights in the sixth, when Cincinnati tied the score on Kane’s double, Wagner’s error, and Mitchell’s triple to right field.

Ewing, relying on his spitball in critical moments, was wild all afternoon. He got into trouble again with two walks in the eighth, but extricated himself by foiling pinch-hitters Otis Clymer and Alan Storke with the bases loaded. The Reds failed to score in their half of the inning despite a walk, a single, and a double.

Pittsburgh gained a 3-2 lead in the top of the ninth inning on a walk, a sacrifice, and Clarke’s slow roller, which trickled into right field for a single after Huggins, in the deepening gloom of the dark afternoon, misread the ball off the bat and broke the wrong way. By this time, the Commercial Tribune noted, both teams “had apparently thrown the game away … several times.”6

After nine innings, Ewing had walked eight men. But he had struck out six and limited the Pirates to six singles, one of them Clarke’s dribbler and another on a misjudged pop fly, and had stranded 10 baserunners. Through many trying moments, the Enquirer‘s Jack Ryder wrote, “He never lost his courage for an instant.”7

Ewing was scheduled to lead off the bottom of the ninth but Reds manager Ned Hanlon called him back and sent Larry McLean out to hit. McLean was another West Coast import, a big catcher whose free-swinging style had early in his career earned him the nickname “Slashaway.”8 He slashed at the first offering from Al “Lefty” Leifield, on in relief of Phillippe. The pitch was over the outside corner of the plate. McLean swatted it down the right-field line and slid head-first into second base with a hustling double. Hanlon sent in Fred Odwell to run for McLean, and Huggins bunted Odwell to third.

Now Lefty Davis was due up. Hanlon went to his bench again and sent up Eddie Tiemeyer, as the Enquirer explained, “in order to put a right-hand batter against Lefty Leifield.”9 Tiemeyer walked. The persistent murmur of the crowd rose to a cacophonous din. From the parking area under the grandstand, what the Commercial Tribune characterized as “unearthly shrieks” issued from a whistle on an automobile, timed and calculated to wreak maximum havoc on Leifield’s nerves.10 Leifield walked Kane as well, loading the bases with one out.

That placed matters in the hands of John Ganzel. In his official debut as the Reds’ captain, Ganzel had stung the ball all day but had no hits to show for it. This time he lofted a little blooper just over the infield and out of the reach of second baseman Ed Abbattichio. As he crossed first base, Ganzel looked back to make sure Odwell and Tiemeyer had touched the plate, then sprinted for the clubhouse ahead of the jubilant fans, who spilled onto the field intent on joyously manhandling any Cincinnati players they could catch.

The underdog Reds had come from behind to win the opener 4-3. The Enquirer’s Jack Ryder exulted over “as grand and game a finish as was ever pulled off on a ball field.”11 The Times-Star’s Charlie Zuber pronounced the contest “undoubtedly … the most exciting opening game ever captured on these or any other grounds.”12 A headline in the same paper assured readers that the Reds’ “alleged yellow streak is [a] thing of the past.”13 The managerial maneuverings of the final inning – three substitutions, a sacrifice bunt, a lefty-righty switch, a crucial run scored by a pinch-runner for a pinch-hitter – were recounted in breathless detail and held up as the supreme demonstration of Ned Hanlon’s baseball acumen. “Every move was made that could be thought of to give the team the slightest advantage,” Ryder wrote, “and the players did the rest.”14

Notes

1 Alfred H. Spink, The National Game, second edition (Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000; reprint of 1911 original), 279.

2 Jack Ryder, “Notes of the Game,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 12, 1907.

3 The Pirates won the National League pennant in 1901, 1902, and 1903. From 1901 through 1906,they won a total of 560 regular-season games, an average of 93.3 per season; www.retrosheet.org, data accessed March 3, 2015.

4 C.H. Zuber, “Reds 3 to 1 Shot for Opening Game,” Cincinnati Times-Star, April 11, 1907.

5 “Notes of the Game,” Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, April 12, 1907.

6 “10,000 Fans See Cincinnati Win the Opening Game of Baseball Season from the Pittsburgs in Whirlwind Ninth-Inning Finish,” Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, April 12, 1907.

7 Ryder, “Notes of the Game.”

8 “Orioles Made an Easy Start,” Baltimore American, April 27, 1901.

9 Ryder, “Notes of the Game.”

10 “Notes,” Cincinnati Commercial Tribune.

11 Ryder, “Pushed Pirates off the Tracks,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 12, 1907.

12 Zuber, “Finish Was the Hottest in Cincinnati History,” Cincinnati Times-Star, April 12, 1907.

13 Zuber, “Alleged Yellow Streak Is Thing of the Past,” Cincinnati Times-Star, April 12, 1907.

14 Ryder, “Notes of the Game.”

Additional Stats

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.