April 17, 1945: Pete Gray, one-armed outfielder, makes major-league debut for St. Louis Browns

On April 17, 1945, just two weeks before Adolf Hitler committed suicide in a Berlin bunker, the St. Louis Browns prepared for Opening Day of the major-league baseball season. Their starting lineup was expected to contain some unfamiliar faces. For several years, as the Allies fought to defeat both Hitler and Japan, hundreds of major-league veteran players had left the game in service to their country. As a result, teams searched far and wide for men with some degree of baseball skill to fill the void among depleted major-league rosters.

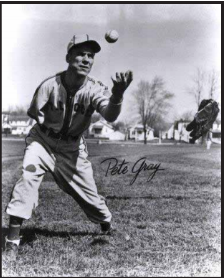

Of all those replacement players, perhaps none was a more unlikely professional than Pete Gray. When he was 6 years old, Gray, a coal-miner’s son from Nanticoke, Pennsylvania, fell off a farmer’s wagon, caught his right arm in the wagon wheel’s spokes, and subsequently lost the arm to an above-the-elbow amputation. In spite of his disability, though, Gray, who was born Peter Wyshner, nonetheless pursued a love of baseball.1 Naturally right-handed, Gray became a left-handed hitter. To defend, he removed almost all the padding from his glove; this allowed a greater feel during catches and also aided Gray in getting the ball out of the glove when he placed the glove under the stump of his right arm. Asked once how he had developed the ability to transition the ball from his glove to his hand, Gray denied any special rehabilitation, explaining instead simply that when playing with the neighborhood kids, “I couldn’t figure how to get the ball out, how to get rid of the ball. And then that just came. It just came, and that was it.”2 So adept did Gray become with his technique that in 1944, when playing in the Southern Association for the Memphis Chicks, he led all league outfielders in fielding percentage.

Gray’s improbable road to the major leagues began very close to home. “I was playing up in Scranton [Pennsylvania],” Gray recalled decades later, “Sunday baseball, and the pitcher, Skelton, he went to Canada, and he knew what I could do. They were playing six days a week. They didn’t play Sunday ball at that time. So, he called me up and he said would I come up there [Canada]. … it’s everyday baseball except Sunday, and we practiced on Sundays.

“So, I went up there, and I done all right. It was a better class of ball than when I [later] went up there to play in the Canadian-American League; older fellas; minor-league fellas; they were paying good money. Then about three, four years later, they got into Organized Baseball, and they sent me a contract. That’s how I got into professional baseball.”

Gray’s first minor-league season, with the Class-C Three Rivers Renards, occurred in 1942. Although Gray was initially slowed by an injury, he still was a tremendous success. “On Opening Day,” Gray said, “I broke my collarbone. I was out for two months and I came back and hit .381.”

That performance caught the eye of the Southern Association’s Memphis Chicks, for whom Gray started the next two seasons. If there were any doubts about his ability, he dispelled them with his performance in 1944. That season, in addition to his league-best fielding, Gray also excelled offensively: in 501 at-bats, he batted .333, smashed five home runs, and also stole 68 bases. For his all-around play, Gray was named the league’s Most Valuable Player.

As Gray produced his signature season in 1944, the Browns that year, for what would be the only time in their history, won the American League pennant. Despite that accomplishment, however, the team drew only 508,644 fans to Sportsman’s Park. Whether through genuine belief in Gray’s abilities or, as some would later contend, a sense of exhibitionism, Browns general manager Bill DeWitt purchased Gray’s contract for $20,000 in the fall of 1944.3 The next spring, Gray would have the chance to make the Browns roster.

As St. Louis’s Browns and Cardinals met the following spring in their annual city exhibition series, the hometown press got their first look at Gray. According to one report, the 30-year-old rookie fared well. He handled 14 defensive chances without a miscue and registered an assist while playing in each of the six games, and also batted .240. In the first inning of the series’ final game, after a single by the leadoff hitter, Gray, batting second, singled to right field and advanced the runner to third, from where the runner subsequently scored on a fly ball. Given that, as well as his full body of work throughout the six games, one baseball scribe assessed that Gray “showed enough to warrant the belief that he will be a useful member of the club.”4 When the Browns broke camp, Gray had made the team.

On April 17, 1945, Opening Day, the Detroit Tigers came to Sportsman’s Park for the first of a three-game series. “The weather was chilly and the crowd disappointingly small, estimated at no more than 4,000,” reported the press, as Browns right-hander Sig Jakucki took the mound.5 Behind him defensively, in left field, was Gray. In an interview he gave in 1989, Gray was not asked, nor did he volunteer, what his thoughts were that afternoon. If he was at all nervous in the field, however, it took just two batters for those nerves to be tested, as the Tigers’ Eddie Mayo doubled to left field. By all accounts, Gray seems to have fielded the ball cleanly and returned it to the infield. Regardless, Mayo’s hit gives us our only glimpse at Gray’s defensive performance that afternoon. It must have been quite a relief to him to get that first one out of the way.

The Tigers failed to advance Mayo beyond second base. As things turned out, however, it didn’t matter, for this game belonged to the Browns. In the bottom of the first inning, left-hander Hal Newhouser took the mound for Detroit. Following a leadoff out, Gray grounded out to shortstop for the second out, but two Browns hits, a walk, and a Tigers error gave the Browns a 2-0 lead, one they would never relinquish. After Paul Richards of the Tigers homered in the top of the third, Gray struck out leading off the bottom of the inning, as Newhouser retired the side in order. Through three innings, the Browns led, 2-1.

Over the next two innings, neither side realized many opportunities. In the Browns’ fifth, however, against Newhouser, Gray momentarily brought the crowd to its feet when he drove a ball to center field for what appeared to be a sure double. But as the ball headed toward the gap, Tigers center fielder Doc Cramer made a tremendous catch, somersaulting as he caught the ball near the ground for the final out. In the seventh inning, in his final at-bat, Gray singled against pitcher Les Mueller, who’d relieved Newhouser, and eventually scored the sixth of seven Browns runs in what became a 7-1 St. Louis victory.

So how good was Pete Gray? In his single season, Gray batted just .218 in 234 at-bats. While he proved adept at hitting fastballs (he struck out just 11 times), the momentum needed to swing his 35-ounce bat — and the force needed to stop it — made it difficult for Gray to adjust to changeups. Also, infielders played in against him, which neutralized Gray’s “skillful bunting.”6 In the field, the fraction of a second it took Gray to transfer the ball from his glove to his hand gave runners that same split-second advantage.

In the opinion of manager Luke Sewell, Gray “didn’t belong in the major leagues and he knew he was being exploited. Just a quiet fellow, and he had an inferiority complex. They were trying to get a gate attraction in St. Louis.”7 Teammate Don Gutteridge opined, “Some of the guys thought Pete was being used to draw fans late in the season when the club was still in the pennant race and he wasn’t hitting well. But I certainly marveled at him. He could do things in the outfield that some of our other outfielders could not.”8

In the end, though, it was left for Gray to judge himself. When asked once how good he might have been if he had had both arms, Gray responded, “Who knows? Maybe I wouldn’t have done as well. I probably wouldn’t have been as determined.”9

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and SABR.org.

Notes

1 Gray changed his name once he began to play professional baseball. His brother, Joe, had been a pro boxer who fought several fights under the pseudonym Whitey Gray, so Pete appropriated the same last name.

2 Pete Gray interview contained in SABR Oral History Collection; conducted April 1989, by Steve Svetovich. Unless otherwise noted, all Gray quotations are from this interview.

3 Pete Gray interview.

4 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 16, 1945: 14.

5 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 17, 1945: 14.

6 Richard Goldstein, “Pete Gray, Major Leaguer With One Arm, Dies at 87,” New York Times, July 2, 2002, http://www.nytimes.com/2002/07/02/sports/pete-gray-major-leaguer-with-one-arm-dies-at-87.html

7 Goldstein.

8 Goldstein.

9 Goldstein.

Additional Stats

St. Louis Browns 7

Detroit Tigers 1

Sportsman’s Park

St. Louis, MO

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.