August 13, 1945: KC Monarchs pay a ‘royal’ visit to Braves Field

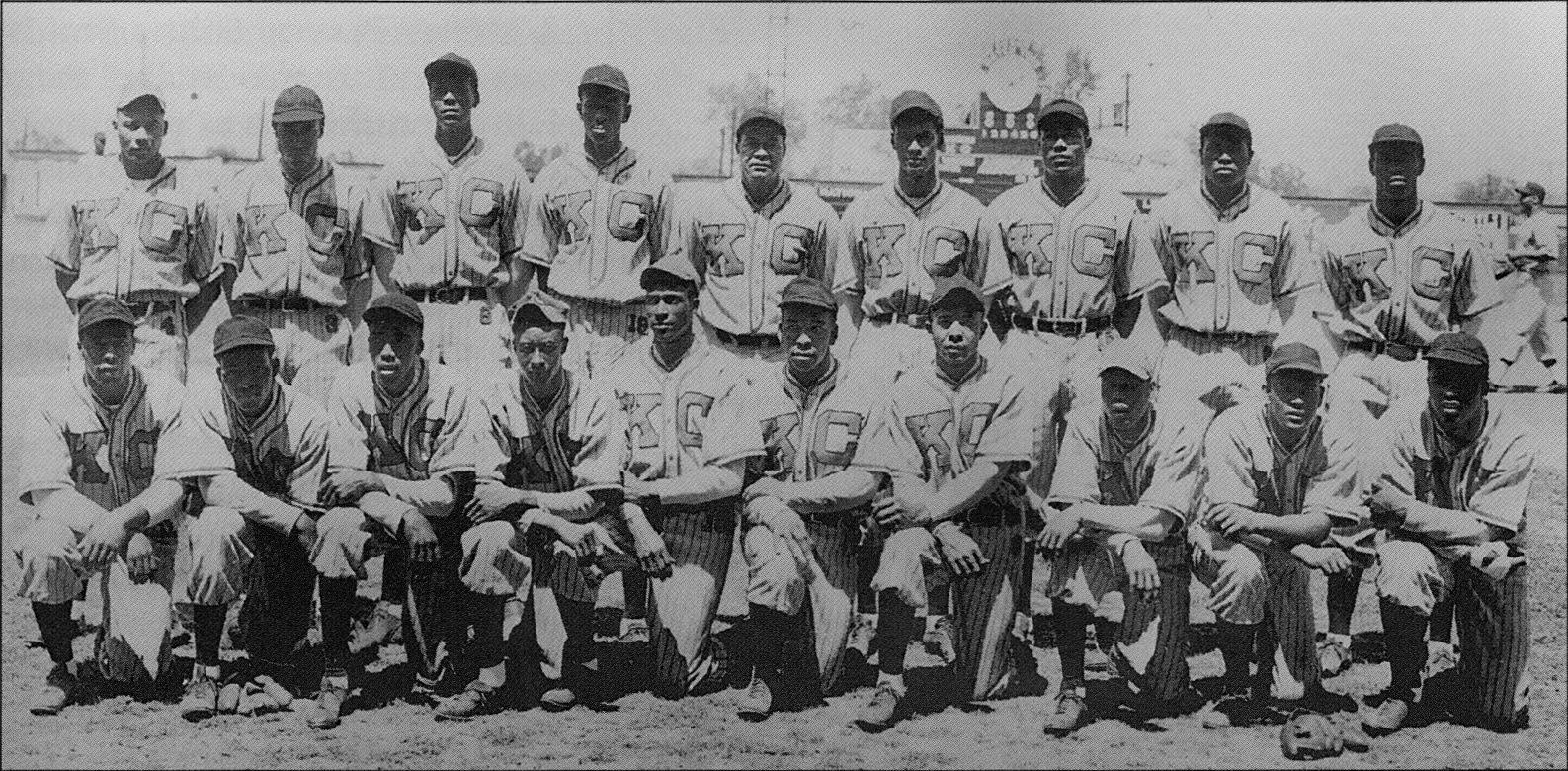

On occasion, the buildup exceeds the event. Such was the case in mid-August 1945 when Braves Field hosted a renowned Negro Leagues team, the Kansas City Monarchs. Though the Monarchs outclassed the local Charlestown Navy Yard Athletic Association, 11-1, the circumstances bookending the entire episode make it a classic in the ballpark’s annals.

On occasion, the buildup exceeds the event. Such was the case in mid-August 1945 when Braves Field hosted a renowned Negro Leagues team, the Kansas City Monarchs. Though the Monarchs outclassed the local Charlestown Navy Yard Athletic Association, 11-1, the circumstances bookending the entire episode make it a classic in the ballpark’s annals.

It was a simple enough idea. The Monarchs were journeying through the East Coast playing black, white, and mixed teams in various cities. The Navy Yard was enjoying a fine season in Boston’s semipro, seven-team Park League and Braves Field was available for a night game since the Monarchs traveled with their own floodlight “arcs.” On a much more important stage, World War II seemed to be finally coming to a conclusion. The game, agreed upon in late July, was slated for August 13. In the two weeks before the game, thousands more American fighting men would die in the final air and sea attacks Japan launched in its own last-ditch defense effort, ending with the United States dropping two atomic bombs.

Boston’s weekly (Saturdays) black press, the Guardian and the Chronicle, started promoting the game in their first August issues. The invitational hook was that LeRoy “Satchel” Paige, the magnificent Monarch moundsman, would hurl at least four innings. In addition, Kansas City’s newest phenom, Jackie Robinson (or “Jake” as the promo ad put it), UCLA’s multi-sports hero, would play shortstop. It was only four months after Robinson was given “a Fenway Park tryout,” but Robinson’s signing with Tom Yawkey was not to be.1

The August contest at the Braves’ Tepee was to be a grand encounter for Curt Fullerton’s Navy Yard nine. Fullerton was a decade beyond his minor-league pitching days in the Pacific Coast League and other leagues and nearly two decades from his less-than-stellar (10-37) short stay with the Red Sox in the 1920s. By the wartime 1940s he was a welder and shipbuilding helper at the Navy Yard.

In 1942 and 1943 the Charlestown squad was good enough to play for the Park League championship against the Dick Casey Club of Dorchester. The Casey Club had captured six straight crowns as the 1945 season began. Again they finished first, edging the Yardmen, 25 wins to 24, beating them 11-0 in a final regular-season matchup. But Fullerton rallied his second-place finishers and as August began so did the three semifinal playoffs, one pitting the defending champs against their Navy Yard stalkers. It was a best-of-seven grudge match, usually drawing large crowds at the neighborhood fields in Dorchester and East Boston.

The Guardian and to a larger extent the Chronicle, which was more sports-minded, trumpeted Satchel Paige’s anticipated arrival.2 Chronicle sports editor William “Sheep” Jackson wrote weekly treatises about why Negroes should be playing major-league baseball. Jackson, a Malden High (just north of Boston) sports star from the 1920s, was a community organizer who lived in Cambridge. The Monarchs visit gave him even more impetus to scroll his hopes for an integrated major league. Not playing favorites, Sheep was not shy in praising the two black players on the Navy Yard’s color-blind club, Buster Reddick (sometime catcher for the local Colored Giants) and outfielder Billie Burke. There were notices and photos of Paige and other Monarch players in the black papers, but the white mainstream outlets (Globe, Herald, Post, and American) printed tiny, one-paragraph blurbs the day before and day of the game – all buried at the bottom of the sports pages. Post columnist Arthur Duffey did promote the game in his space that morning, calling Paige, “one of baseball’s outstanding showmen.”

As Monday, August 13, unfolded, the host Braves beat the Pittsburgh Pirates 6-4 despite Lowell, Massachusetts, native Johnny Barrett’s greatest career day (four hits, two home runs, two RBIs). Attendance was about 2,100. Later that same afternoon the Navy Yard edged Casey Club, 5-4, to even their series at two wins each. An hour later, near 7:30, Fullerton’s spent team was at Braves Field welcoming the flashy Monarchs to their Gaffney Street home, just off Commonwealth Avenue. Good seats were $1.20 (60 cents for the bleachers). War bonds were going to be raffled off to what became a crowd of nearly 5,000. Trumping all of this sports activity, however, was the slowly leaking news of the long-prayed-for official government confirmation that Japan was finished. People went crazy celebrating. Boston joined in (the Post said 750,000 celebrants hit the streets) and so the ballgames immediately took a back seat. Yard players’ emotions must have been swirling. By simple job definition they were more attached to the war effort than most Hub dwellers and had just played a cliffhanger with the Casey Club. Now they faced the star-studded Monarchs. There was plenty of hoopla but one thing was missing – Satchel Paige.

He didn’t show up, and “Sheep” Jackson later reported that the announcement (blaming car trouble – more specifically a tire blowout) was not made to the expectant crowd until the eighth inning.3 But the attending fans were not completely cheated because Monarch stalwart Hilton Smith stepped in and threw a five-hit, 11-1 win. During KC’s Negro League championship years, Smith had done more pitching than vagabond Paige and was only a bit shy of Satchel’s numbers in 1945, both then being age 38. Paige (5-4) was the drawing card, Smith (2-4) the lovable veteran, but the much younger Booker McDaniels was the team’s real workhorse (7-4, 118 innings, more than Smith and Paige combined).

Much to the chagrin of researchers, there is no box score in any newspaper. Very short stories by the dailies gave the score, mentioned Smith and Robinson’s play, critiqued the lights (fair), and all made note of Paige’s absence. On Tuesday morning the Globe ran a line score showing that the Monarchs scored eight runs in the last two innings. (Its front page blared “SURRENDER DUE” and the North Shore’s Newburyport Daily News had “JAPS GIVE UP” greet its readers, while the Boston Post proclaimed “WAR IS OVER”). Only Jackson saved future fans a bit of baseball history by giving some details the following week, and he included a second agenda. He was livid that Paige had not shown up despite the prideful black community’s promotion. The outspoken writer came down heavily on anyone he thought to be insulting black people, be they white (usually) or in this case, black.

The front page of the competing Guardian of August 18, headlined, “Monarchs Win Easy Victory” but did not supply any details of play.

Jackson had glorified Paige’s iconic baseball life in the August 11 Chronicle, and held back from any comment on August 18, but in the August 25 issue his “Sports Shots” column excoriated the missing Monarch. “… His actions towards the man who had planned, worked and spent all sorts of money for advertisement for the coming of the great colored baseball Messiah was little less than scandalous. He should stay in the mid-west to clown and kid his way through the Negro baseball league. It is just another black mark against the Negro American League. … Satch, in the eyes of Bostonians, is just a Great Social Error and Bust.”4

Sheep was even more embarrassed because he had written a glowing column on Paige in the June 30 edition, a month before the Monarchs decided to make their Hub stop. After dealing with Paige on August 25, Jackson switched mood and gave the only game notes now available, applauding the efforts of those who exhibited their skills for the Braves Field crowd. “Though outclassed, the Navy Yard did itself proud,” he noted, “with (John J. “Red”) Chappie, (Charles “Gubby”) McArdle, and black catcher Reddick playing as brilliantly as the pros themselves.” He lauded Robinson’s completeness as shortstop Jackie had two hits (one a drag bunt), stole four bases (including home), and fielded with style. Of Hilton Smith (Hall of Fame 2001), the irked Jackson beamed, “… hurled better than Satch. (Bill) Williams at second base was better than all right.” Jackson ended with, “The crowd was good, with many a white fan really enjoying the game and applauding Robinson and Smith on many occasions. It was the first time a night game was played in any Big League Boston (park). It might be the beginning.”

As for the Navy Yard’s quest for glory, they lost to the Caseys the next day, but then beat them twice, including a 1-0 classic, to secure a place in the finals against the Linehan Club. Jumping to a three-games-to-none advantage (plus a 0-0 tie), Fullerton’s boys hung on to take the series, four wins to two, for their only Park League championship. Joe T. Callahan of East Boston (High School), who pitched for Northeastern University, the Bees (1-2 in a career of 32 innings), and six minor-league clubs, won the final game, 5-1. Sadly, Callahan would die of heart disease complications in May 1949 at age 32.

This article appeared in “Braves Field: Memorable Moments at Boston’s Lost Diamond” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and Bob Brady. To read more articles from this book, click here.

Sources

Baseball Reference.com (Monarch player stats from 1945).

Boston Park League website (history of league championships).

Minor League Baseball Encyclopedia, third edition, online (Navy Yard players).

Retrosheet.org.

Boston American, Boston Globe, Boston Herald, and Boston Post. August 1 through 14, 1945.

Boston Chronicle, June, July, and August, 1945.

Boston Guardian, July and August, 1945.

Boston Navy Yard News, May 5, June 16, June 30, July 28, August 11, August 25, and September 8, 1945. Courtesy of the Boston National Historical Park Archives (museum curator David J. Vecchioli).

Notes

1 Under a front-page headline of “Big Time Game At Braves Field” on August 11, 1945, the Boston Guardian ran this brief account of Robinson’s Fenway Park tryout within the promotional story: “After a recent workout with the Boston Red Sox, manager Joe Cronin said he (Robinson) was the best prospect he had seen for some time.”

2 Ibid. The front page had a picture of Paige and a caption that said in part, “… he will be hailed by thousands of baseball fans and others who appreciate his amazing performances as contributing to better interracial understanding.”

3 The Guardian gave a few details, score, crowd, who donated, and who won the war bonds but had an entire paragraph on Paige’s absence. “It was announced that his car broke down on the way to the Hub. Newspaper reports from Washington said that Paige had been beaten by a DC policeman Thursday of last week. It is alleged that the officer punched him twice in the eye and that the injury might keep the star pitcher out of the game for a week. The cop is said to have accused Paige of failure to obey traffic directions.” Though often found in various claimed eyewitness accounts, the DC story is never documented as to a paper source. It is not in the Washington Post or Baltimore Sun or The Sporting News, to name three. It is claimed that DC officer Robert Lewis, not knowing it was Paige, socked Satchel for nearly running him over at a tight intersection. Satchel’s reputation with traffic laws was not good and he drove a big, fancy car, usually very fast.

The Monarchs schedule was exhausting. They played in Pittsburgh on August 8 and in Washington the next day. Icon/showboat Paige drove his own vehicle and came too late to pitch for his Monarchs in DC so he tossed three scoreless innings for the Birmingham Black Barons in the second game of the doubleheader, which they lost, 13-7. It was after that game on August 9 that he got into the fracas with the policeman.

The blowout was mentioned in the Boston Globe, August 14, 1945.

4 William “Sheep” Jackson, “Sports Shots,” Boston Chronicle, August 25, 1945, 7.

Additional Stats

Kansas City Monarchs 11

Charlestown Navy Yard 1

Braves Field

Boston, MA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.