August 18, 1865: Eurekas almost strike gold against the champion Atlantics

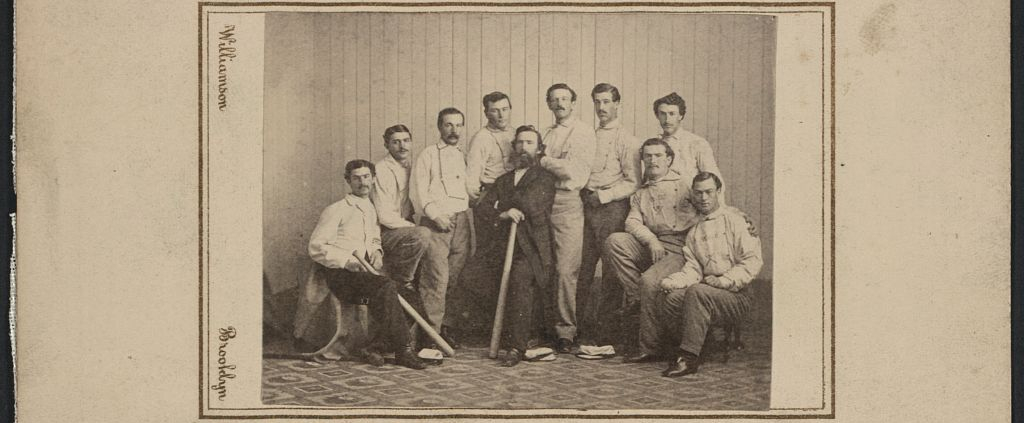

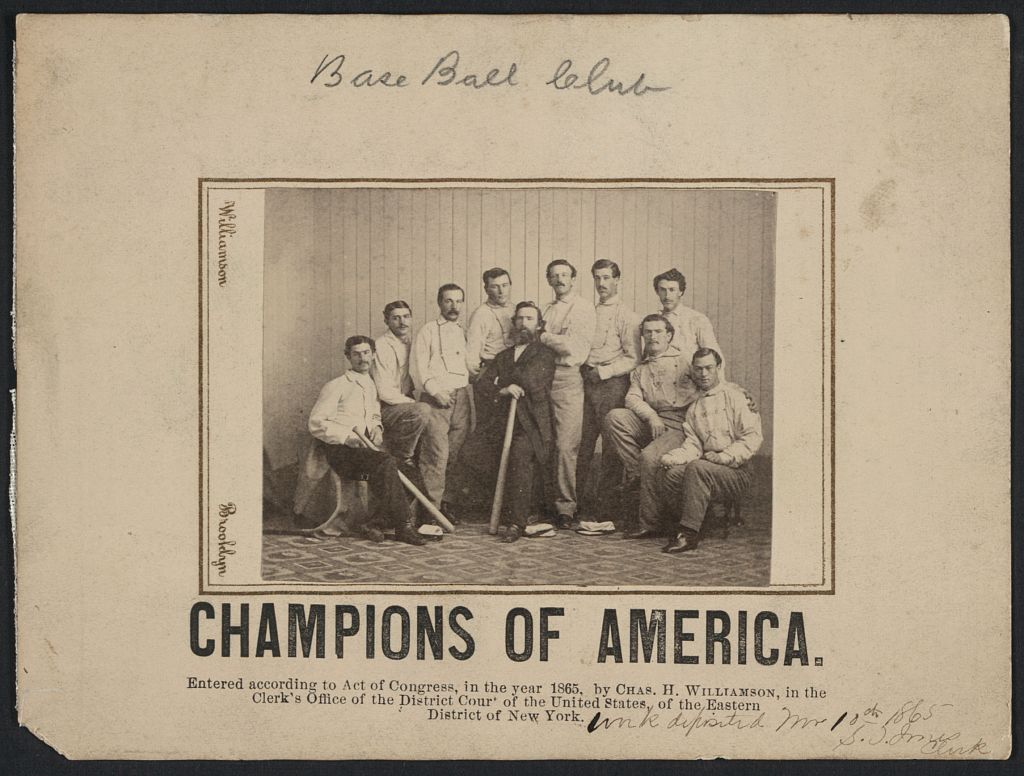

This 1865 photograph of the Atlantics of Brooklyn by Charles H. Williamson depicts the “Champion Nine” of 1864 and was given to opposing teams who played the Atlantic Club. (Library of Congress)

The Atlantic Club of Brooklyn had every reason to feel confident as they traveled to Newark, New Jersey, on August 18, 1865. Their starting nine, the recognized champions of base ball since September of 1864, hadn’t lost a match in almost two years. Four days earlier, they had defeated the Mutual Club, their strongest rivals, for the second time in as many weeks.

These two wins were very significant. Before the National Association was founded in 1871, the championship was defended against clubs affiliated with the National Association of Base Ball Players in “home-and-home” series. Only by defeating the champions twice in three games – one home game for each club and then a third match played at a neutral ground, if necessary – could the title change teams. By winning twice against the Mutuals, the “Bedford Boys” had passed their most difficult test. They had every reason to believe they could coast to the end of the 1865 season without fear of losing the pennant.1

Their opponent on August 18 was the Eureka Club of Newark. The Eurekas were a well-respected nine, but they were perceived to be a level below the Atlantics and Mutuals. The Eurekas even admitted as much; the club’s stated goal before the match was “keeping down the score.”2

The Atlantics were bringing their strongest nine to Newark; among them were Dickey Pearce, Joe Start, and Charlie Smith. Pearce, who is best known for being the first man to play shortstop as an infield position rather than as a fourth outfielder, was also a gifted catcher. He manned the backstop in Newark.

Start and Smith were widely perceived as the best first and third basemen respectively, by their contemporaries. Start, acknowledged as the first to position himself near first base instead of always keeping one foot on the bag, was also one of the game’s first great power hitters.3 Smith, meanwhile, was called “the king of third basemen” by Harry Wright.4 Smith was also a great hitter and normally near the team lead in runs.5

From the time the champions arrived, however, circumstances began to conspire against them. The game started 90 minutes late due to the delayed arrival of the Eurekas.6 Furthermore, the decision was made not to play with the livelier ball that the Atlantics were used to. Only the dimensions and weight of the ball were regulated in 1865; some teams played with a livelier ball, while other teams elected for a dead ball. The Atlantics always elected for the lively ball when they had the choice. The Eureka Club decided that the day’s game would be played with a more deadened ball, limiting the Atlantics’ power advantage.7

Tom Pratt was the Atlantics’ starting pitcher. He was their regular pitcher from 1863 through 1865 and then became their “change pitcher” after the arrival of George Zettlein in June of 1866.8 For the Eureka Club, Charles Faitoute stood in the pitcher’s box. Faitoute was in his fourth season with the club, having pitched for the Eurekas in 1862-63, then rejoining in 1865 after taking a year off.9

Once the game began around 3:30 P.M., the Brooklyn nine immediately began to show signs that they were not at their best. Eureka’s Fred Calloway led off with a single and attempted to steal second. Pearce airmailed his throw over second baseman Fred Crane, allowing Calloway to reach third.10 The Eureka’s second hitter, Charles Thomas, drove Calloway home with a single. Thomas advanced to second when Pearce overthrew Start at first base, possibly on a pickoff play, although the Clipper’s play-by-play account is unclear on the exact circumstances.

After Thomas advanced to third base on Al Littlewood’s ground out to Pratt, Edward Pennington scored the runner with another base hit. Pennington stole second and solicited another wild throw from Pearce, this one being so poor that Pennington managed to score from first base.11 Pearce’s three throwing errors gifted the Eureka club three runs.

The Atlantics’ Tom Pratt hit a solo home run in the top of the second, but Brooklyn’s fielding follies continued in the bottom of the inning. This time it was third baseman Smith who made two crucial errors: first by missing Thomas’ groundball, which allowed the Eureka shortstop to reach first base, and then by muffing a ball that could have been more easily played by shortstop Joe Sprague.12 The Eurekas took advantage of these misplays to tally another six runs, making it 9-1.

Even Start, who later earned the nickname Old Reliable, became afflicted with an uncharacteristic case of the muffs. The newspaper accounts were in disbelief at Smith’s and Start’s fielding lapses. The Brooklyn Union remarked, “We could scarcely believe at one time that Smith was playing at third base, so carelessly did he field at times. Start, too, allowed balls to pass him that he usually holds in style.”13

Despite all this, the Atlantics scored four runs in their half of the third inning. The Eurekas were shut down in the bottom of the inning for their first whitewash. Pearce began the Atlantic half of the fourth by uttering the club’s famous rally cry: “Now we’re off!”14 That phrase had preceded other come-from-behind rallies over the years.15 So frequent were these rallies that the phrase “Atlantic luck” eventually became a turn of phrase among base ball writers of the era.16

On this day, however, Pierce’s call to action was met by a ruthless response from the Eureka fielders. Peter O’Brien grounded out to shortstop. Joe Sprague was put out on a foul tip that was caught on the first bounce by the Eurekas’ catcher, R. Heber Breitnall. (In 1865, a bound out could be made on a foul tip to the catcher at any point in the at-bat.) Pearce made his out in the same fashion as Sprague. It was a quick one-two-three inning.17

The Atlantic Club did put together five runs in the fifth inning to take a 10-9 lead. The Eurekas responded with two runs of their own in the bottom half to retake the lead, 11-10. In the Brooklyn sixth, Start began to make up for his loose fielding via his bat. He hit a clean two-run homer over Littlewood’s head in center field.18 Start’s smash gave Brooklyn the lead once again, 12-11.

The seventh began with the same cry as the fourth: “Now we’re off!”19 Sid Smith started the inning with a hit and scored on a hit from O’Brien. O’Brien, however, was put out by “by a ball splendidly thrown by (Breitnall).”20 Sprague followed with a groundout to Theo Bomeisler at third, and Pearce bounded out to Breitnall on a foul tip.21 Two classic rally cries from the undefeated champions of base ball led to only a single run, but they still held on to a 13-11 lead after seven innings.

In the top of the eighth, Start struck his second home run in as many at-bats, driving Smith home. Start batted 4-for-5 with a double, two home runs and four runs scored.22 The Clipper stated its verdict plainly: “But for Start’s fine batting, the Atlantics would have returned home minus the [victory], for assuredly nothing else saved their defeat.”23 The Atlantic batters strung together a few more hits to build an 18-11 lead, but the inning ended on another foul-tip bound out by Pearce.

Pearce continued to struggle. The fans behind home plate made every effort to get in front of Breitnall’s passed balls, while they cleared a path for Pearce’s passed balls to keep rolling farther out of play. Pearce let his emotions boil over after one such instance and cursed at the crowd in anger.24 Displays of the sort were scandalous in an era where base ball was still a gentleman’s game. The Union allowed that the crowd’s actions were “annoying … but nothing excuses blasphemy on any occasion.”25

Through it all, the Atlantic Club still entered the bottom of the ninth with a 21-15 lead. Sprague started the inning by committing a two-base throwing error on a batted ball from Faitoute. Bomeisler followed with a bound out to Pearce. The Eurekas then began stringing hits together. Number-nine hitter Edward Mills hit safely, followed by Calloway, Thomas, and Littlewood. Faitoute and the other four men came around to score. Littlewood made the last run on a fielder’s choice by Pennington. The score was now 21-20, the bases were empty, and there were two outs in the ninth.26 The next batter up was the Eurekas’ right fielder, whom history knows only as Rogers.

Rogers lofted the ball near the first-base line. Pearce watched the ball struck while Start, who had to react immediately, prepared to try to make a difficult catch on the fly. The “fly rule” had become the standard after the national convention in December 1864, meaning that fielders could no longer catch a fair ball on the first bounce and have it called an out.27 The bound out, however, was still legal on foul balls.

Pearce called out to Start to “get behind it.”28 His call was meant to inform Start that the ball was going to bounce in foul ground. Start adjusted on Pearce’s command and caught the bound out to end the game. The Atlantics had narrowly escaped defeat, 21-20.

The return match of the home-and-home series was played on August 31. This time, it was a 38-37 Atlantics victory. The champions finished the 1865 season 18-0, holding on to the pennant for their second consecutive season. They held the pennant until the Union Club of Morrisania defeated them twice in 1867.

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Kurt Blumenau and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 William J. Ryczek, When Johnny Came Sliding Home: The Post-Civil War Baseball Boom, 1865-1870 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Press, 1998), 69-70.

2 “Base Ball,” Brooklyn Daily Union, August 19, 1865: 1.

3 Irwin Chusid, “Joe Start,” SABR BioProject, accessed January 24, 2025, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/joe-start/.

4 Craig B. Waff and William J. Ryczek, Base Ball Founders: The Clubs, Players and Cities of the Northeast That Established the Game (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Press, 2013), 465.

5 Waff and Ryczek, 427, 431.

6 “Base Ball Circles.” Brooklyn Eagle, August 19, 1865: 2.

7 “Base Ball,” Brooklyn Union, August 19, 1865.

8 Waff and Ryczek, 463; Brooklyn Union, June 13, 1866: 4.

9 Waff and Ryczek, 753..

10 “The Third Match for the Championship,” New York Clipper, August 26, 1865: 2.

11 “The Third Match for the Championship.”

12 “The Third Match for the Championship.”

13 “Base Ball,” Brooklyn Daily Union.

14 “The Third Match for the Championship.”

15 “Base Ball,” Brooklyn Daily Times, September 14, 1866: 3.

16 “The National Game,” New York Herald, June 1, 1870: 13.

17 “The Third Match for the Championship.”

18 “The Third Match for the Championship.”

19 “The Third Match for the Championship.”

20 “Base Ball.”

21 “The Third Match for the Championship.”

22 Joe Start’s modern box-score line was compiled using the Clipper’s play-by-play account from August 26.

23 “The Third Match for the Championship.”

24 “Base Ball.”

25 “Base Ball.”

26 “The Third Match for the Championship.”

27 “The Base Ball Convention,” New York Clipper, December 24, 1864: 2.

28 “Base Ball Circles.”

Additional Stats

Atlantic Club of Brooklyn 21

Eureka Base Ball Club of Newark 20

Eureka Grounds

Newark, NJ

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.