August 23, 1860: No gentlemen’s game, Excelsior vs. Atlantic

The unofficial concept of a local “champion” among the senior clubs in the Greater New York City region was initially associated with the Atlantic of Bedford club, which by mid-1859 had compiled a seemingly invincible record. The club’s last game loss had come at the hands of the Gothams on October 30, 1857, and its only match loss, to the Empires of New York, had occurred in 1855-56.1

Although the Atlantics eventually lost, 22-16 to the Eckfords of Brooklyn on September 8, 1859, reporters used the words champion and championship more frequently in 1860, especially in accounts of games involving the Atlantics.

Although the Atlantics eventually lost, 22-16 to the Eckfords of Brooklyn on September 8, 1859, reporters used the words champion and championship more frequently in 1860, especially in accounts of games involving the Atlantics.

When the Excelsiors of South Brooklyn challenged the Atlantics in early 1860, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reporter perceived the match as creating “unusual interest,” because “it will decide which Club is entitled to the distinction of being perhaps the “first nine in America.”2

The Excelsior challenge was seen as particularly strong because the club had added pitcher James Creighton and left fielder George Flanly in the offseason, and also because of the Excelsiors’ tour through upstate New York, during which they defeated the strongest clubs of Albany, Troy, Buffalo, Rochester, and Newburgh.

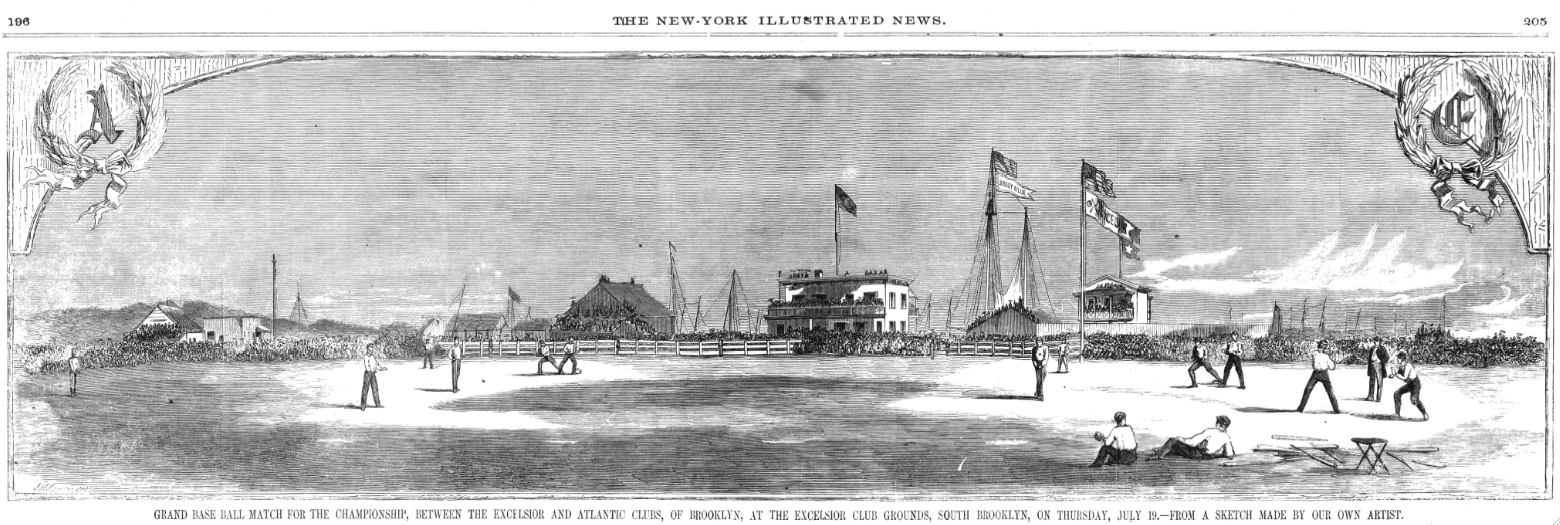

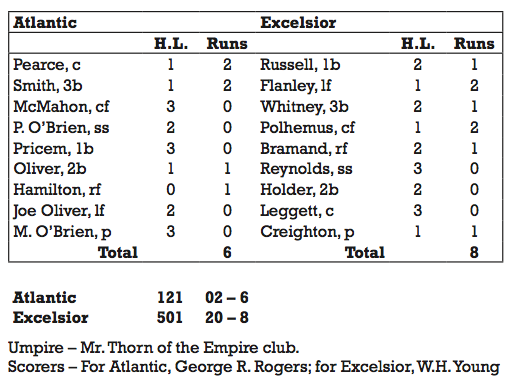

The Atlantics, although winning all of their early 1860 games, were perceived as less competitive.3 This may have been partly due to the absence of Folkert Rapelje Boerum, the team’s captain and regular catcher, who had been on an extended trip to Europe since the spring, and to injuries suffered by Matty O’Brien, the regular pitcher, and at least one other unidentified player. These circumstances may help to explain the Excelsiors’ 23-4 victory on the Excelsior grounds on July 19.4

This apparently spurred the Atlantics, who resoundingly defeated the Mutuals of New York, 34-15, on July 30, and then attained closely-contested victories on their home grounds in Bedford over the Excelsiors (15-14 on August 9),5 the Enterprise (16-14 on August 17), and the Mutuals (26-24 on August 20). Commenting on the last game, the reporter for Porter’s Spirit of the Times observed, “The playing of the Atlantics, both in fielding and batting, was that superior character which has won for them, for so many years, the right and title to the Base Ball Championship.”6

On August 21 a Porter’s Spirit commentator caught the mood of the baseball community in the metropolitan area anticipating the meeting between the Atlantics and Excelsiors: “…The interest and excitement in the trial waxes warmer and warmer, and … it is now generally admitted that it will be witnessed by the greatest gathering of spectators ever assembled on any base ball field.”7

The size of the expected crowd raised concerns about the playing site. A commentator in Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times declared for the New York Parade Ground, “a beautiful level field of some thirty acres” with “ground as smooth as a floor” capable of accommodating 20,000 to 30,000.8

Instead, club officials settled on the Putnam Club grounds. “There are but poor accommodations [there] for so large a crowd as will be undoubtedly present,” the Eagle reporter asserted.9

On game day at least 15,000 spectators — including, according to the Eagle, delegations of ballplayers from Philadelphia, Baltimore, Boston, Albany, Troy, Buffalo, Rochester, Poughkeepsie, and other cities — converged on the Putnam grounds, a large police force keeping them off the playing field itself.

In the fifth inning, with the Excelsiors leading 8-4, a fateful sequence of events began. Dickey Pearce reached first base after catcher and team captain Joe Leggett missed a foul tip and second baseman John Holder muffed a grounder. Charley Smith then made a “splendid strike” to left field that scored Pearce and enabled Smith to reach second base. Archie McMahon followed with a grounder to left field which, though fielded well by third baseman John Whiting, allowed Smith to score, McMahon eventually reaching second. One out later, McMahon ran to third, being ruled safe and then out when his hand came off the base. The New York-based Sunday Mercury reported that umpire R.B. Thorn’s “righteous decision raised a perfect howl among the outsiders,” who “began calling ‘Not out!’ in a very boisterous manner, and indulging in other insulting expictives [expletives?] against the umpire, and the captain and members of the Excelsior nine.”10

The New York Clipper reporter (most likely Henry Chadwick) identified the troublemakers as members of “the betting fraternity.” McMahon’s extended dispute of the umpire’s call, in Chadwick’s view, encouraged the rowdy behavior.11 At that point, Leggett “distinctly proclaimed” that he would pull his players off the field if the behavior continued.

The rowdiness briefly diminished, but resumed more strongly during the sixth inning. With one out pitcher Matty O’Brien missed Leggett’s ball both on the fly and the bound, and his brother Peter’s throw from shortstop to first narrowly missed retiring Leggett. Creighton then sent a ball toward Peter O’Brien, who threw it to second baseman John Oliver to put Leggett out. Oliver’s throw to first, however, was missed by John Price, and allowed Creighton to reach base safely. “The rowdy spirit of the crowd again began to display itself still more forcibly,” Chadwick wrote. “So insulting were the epithets bestowed on the Excelsiors, that Leggett decided to withdraw his forces from the field.”

According to the Sunday Mercury reporter, Leggett offered the game ball to the Atlantics. Matty O’Brien objected and stated a desire to continue, but the Excelsior captain remained adamant about not playing. He did, however, consent to O’Brien’s proposal to call the game a draw.

The wisdom of Leggett’s action was much debated in the New York press. Chadwick believed Leggett “acted wisely,” but was disappointed that the Atlantics did not support him, “as that was the only method of putting a stop to the outrageous conduct of the low gambling set that were present on the occasion.” On the other hand, an anonymous writer calling himself “Home Run” contended that Leggett lacked sufficient cause to pull his men when “the field was clear, the rope was perfect around its entire extent, and every player could exhibit as perfect play as he was capable of.”12

The wisdom of Leggett’s action was much debated in the New York press. Chadwick believed Leggett “acted wisely,” but was disappointed that the Atlantics did not support him, “as that was the only method of putting a stop to the outrageous conduct of the low gambling set that were present on the occasion.” On the other hand, an anonymous writer calling himself “Home Run” contended that Leggett lacked sufficient cause to pull his men when “the field was clear, the rope was perfect around its entire extent, and every player could exhibit as perfect play as he was capable of.”12

Thorn conceded that neither club “won” the game “inasmuch as it was brought to an abrupt termination by influences outside of the parties interested in the match.” But he argued that because the stoppage of the game was not by mutual consent, he had to declare “according to the rules” that the Excelsiors had forfeited the game to the Atlantics.13 The debate on the outcome continues to this day.

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Notes

1 Craig B. Waff, “1860.60 Atlantics and Excelsiors Compete for the ‘Championship,’ July 19, August 9, and August 23, 1860,” Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game, vol. 5, no. 1 (Spring 2011), 139-142.

2 “City News and Gossip: Base Ball—The Excelsiors,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, vol. 19, no. 165 (July 13, 1860), 3.

3 In an account of a game played against the Putnams of Brooklyn on June 29, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reporter observed that “the Atlantics were far below their proverbial style of play.” The New York Clipper reporter likewise observed a few weeks later that “this season the general play of the [Atlantics] has not been as good as that of last year, and we have noticed occasionally of late, a perceptible falling off in the ability that has hitherto been characteristic of their play.” Only the Putnam game had been competitive, and thus “a relaxed state of discipline has been induced that has had an unnerving effect.” See “City News and Gossip: Base Ball—Atlantic vs. Putnam,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, vol. 19, no. 155 (June 30, 1860), 3; “Excelsior vs. Atlantic: The Match for the Championship,” New York Clipper, vol. 8, no. 14, 108.

4 For accounts of the game, see “City News and Gossip: Base Ball—Excelsiors vs. Atlantic,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, vol. 19, no. 171 (July 20,1860), 3; “Base Ball: Excelsior vs. Atlantic—The Excelsiors Victorious—The Champion Club Beaten,” New-York Times, vol. 9, no. 2755 (July 20, 1860), 8; “Excelsior vs. Atlantic: The Match for the Championship,” New York Clipper, vol. 8, no. 14 (July 21, 1860), 108;; “Out-Door Sports: Base Ball: Match between the Champion Clubs,” [New York] Sunday Mercury, July 22, 1860, 5; “Out-Door Sports: Base-Ball: Excelsior vs. Atlantic—The Excelsior Victorious—The Champion Club Beaten,” Porter’s Spirit of the Times, vol. 8, no. 22 (July 24, 1860), 340; “Base Ball—Excelsior vs. Atlantic,” Spirit of the Times, vol. 30, no. 25 (July 28, 1860), 304; “Grand Match of the Season: Excelsior vs. Atlantic,” New York Clipper, vol. 8, no. 15 (July 28, 1860), 116; “Out-Door Sports: Base Ball: Match between the Excelsior and Atlantic Clubs,” Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times, vol. 2, no. 21 (July 28, 1860), 331.

5 For accounts of the game, see “Base Ball: Grand Ball Match at Bedford,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, vol. 19, no. 189 (August 10, 1860), 2; “Out-Door Sports: Base Ball,” New-York Times, vol. 9, no. 2773 (August 10, 1860), 8; “Out-Door Sports: Base Ball: Return Match Between the Atlantic (of Bedford) and the Excelsior (of South Brooklyn), [New York] Sunday Mercury, August 12, 1860, p. 5; “Out-Door Sports: Base-Ball: Atlantic vs. Excelsior,” Porter’s Spirit of the Times, vol. 8, no. 25 (August 14, 1860), 388;“Grand Base Ball Match: The Atlantics Victorious: Excelsior vs. Atlantic,” New York Clipper, vol. 8, no. 18 (August 18,1860), 141; “Out-Door Sports: Base Ball: Atlantic of Bedford vs. Excelsior of Brooklyn,” Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times, vol. 2, no. 24 (August 18,1860), 378.

6 “Out-Door Sports: Base-Ball: Atlantic vs. Mutual,” Porter’s Spirit of the Times, vol. 8, no. 27 (August 28, 1860), 420-21.

7 “Out-Door Sports: Base-Ball: Excelsior vs. Atlantic,” Porter’s Spirit of the Times, vol. 8, no. 26 (August 21, 1860), 408.

8 “Out-Door Sports: Base Ball: Grand Base Ball Match—Atlantic vs. Excelsior,” Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times, vol. 2, no. 26 (September 1, 1860), 405.

9 “Base Ball: Matches to Be Played: Atlantic vs. Excelsior,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, vol. 19, no. 198 (August 21, 1860), 2; “Base Ball: Atlantic vs. Excelsior,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, vol. 19, no. 199 (August 22, 1860), 3.

10 “Out-Door Sports: Base Ball: Atlantic vs. Excelsior—The Conquering Match,” [New York] Sunday Mercury, August 26, 1860, 5. The quoted passage may contain the first specific use of the term sliding to describe that aspect of the running game. Paul Dickson’s The Dickson Baseball Dictionary, 3rd ed. (New York: Norton, 2009), 787-788, cites an 1866 newspaper article for “1st use.”

11 “Ball Play: Third Grand Match at Base Ball: The Game Broken Up by Rowdies: A Drawn Game: Excelsior vs. Atlantic,” New York Clipper, vol. 8, no. 20 (September 1, 1860), 154.

12 “Out-Door Sports: Base-Ball: Excelsior vs. Atlantic—Game Broken up in a Row—Card from the Umpire—Letter from ‘Home Run’,” Porter’s Sprit of the Times, vol. 8, no. 27 (August 28, 1860), 420.

13 Thorn defended his position in a letter to the editor that appeared in numerous newspapers, e.g., “Out-Door Sports: Base-Ball: Excelsior vs. Atlantic—Game Broken up in a Row—Card from the Umpire—Letter from ‘Home Run’,” Porter’s Spirit of the Times, vol. 8, no. 27 (August 28,1860), 420; R.H. Thorn, Umpire, “Out-Door Sports: Base Ball: Decision of the Umpire,” Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times, vol. 2, no. 26 (September 1, 1860), 405; “Ball Play: Third Grand Match at Base Ball: The Game Broken Up by Rowdies: A Drawn Game: Excelsior vs. Atlantic – the Umpire’s Decision,” New York Clipper, vol. 8, no. 20 (September 1, 1860), 154.

Additional Stats

Excelsior of S. Brooklyn

vs. Atlantic of Bedford

Putnam Club Grounds

New York, NY

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.