December 4, 1920: Big-time college football comes to Braves Field

The 1920 Boston College-Holy Cross football game was an important milestone in New England sports history. Sometimes the most intense rivalries are between family members. The annual game, which began in 1896, always attracted enormous interest among Catholics. Cardinal William O’Connell, the leader of the Archdiocese of Boston, took a personal interest in the annual game. He attended practices and personally awarded an annual trophy named after himself to the winners.1

The 1920 Boston College-Holy Cross football game was an important milestone in New England sports history. Sometimes the most intense rivalries are between family members. The annual game, which began in 1896, always attracted enormous interest among Catholics. Cardinal William O’Connell, the leader of the Archdiocese of Boston, took a personal interest in the annual game. He attended practices and personally awarded an annual trophy named after himself to the winners.1

But the hype surrounding the game was unlike any previous contest. Traditional football powers, such as Harvard, Princeton, and Yale, increasingly had to share the stage with other university teams. The football teams’ success was a source of Catholic pride in the predominantly Protestant United States. The interest in the BC-Holy Cross game had outstripped their campus playing fields. A supporter of the Eagles was quoted as saying: “The Boston College football has done as much for the cause of Ireland as De Valera himself.”2

Outscoring its opponents by 181-16, BC was recognized as one of the best college teams in America in 1920.3 Championships weren’t awarded through a playoff or bowl. At stake was its second consecutive Eastern championship, a consensus among fans and the press that it was best Catholic football team in the East.

Both teams had proven themselves against the best. Harvard’s ranked team barely survived a too-close-for-comfort 3-0 win over Holy Cross. Boston College was one of the biggest stories in the country. For the second year in a row, the Eagles defeated Yale in New Haven. An eyewitness to BC’s upset win at Yale, future Harvard Hall of Famer Charlie Brickley, observed: “They are one of the best football teams I ever saw and the way they played Yale would have beaten any team in the country.”4

The Eagles were coached by Frank Cavanaugh, who was at BC from 1919 to 1926. The Iron Major was a World War I hero. (In 1927 the College Football Hall of Famer was lured to the bright lights of New York at Fordham. His offensive line, dubbed the Seven Blocks of Granite, brought football fame and fortune to the Jesuit school.) BC’s other future Hall of Famer on this day was All-American captain Luke Urban at end. Tony Comerford, the opposite end, was also a significant threat. BC’s Jimmy “Fitzy” Fitzpatrick, the starting halfback, was a game-breaker, but was unavailable for this game because of a dislocated shoulder.5 Besides being the team’s leading scorer, Fitzy was a fast runner, an ambidextrous passer, and perhaps the greatest kicker in football. His punting average was over 65 yards and he drop-kicked many long-range field goals. His clutch field goals had defeated Yale, Georgetown, and Holy Cross twice. But star quarterback Phil Corrigan, who had been injured much of the season, was finally healthy enough to return to the starting lineup. It was good timing: Corrigan was also the backup kicker/punter.

Holy Cross, at 5-2, was no slouch. Its signature win was a 3-0 shutout over then-unbeaten Syracuse. The Purple had a stout line and strong defense, boasting a 220-pound left guard. Its main threat was left halfback Chick Gagnon. Practices before the game were used by coach Cleo O’Donnell as open competitions to determine who would start at left tackle, fullback, and end in the finale.

The rivals had split their series, winning eight games apiece. Boston College had won the last three. In 1919 BC, at Fenway Park, upset the heavily favored Crusaders before a record-setting Boston football crowd of 15,000.

But the attendance for the 1920 game shattered that record. Most reports indicated that about 30,000 attended the game. But there were some estimates that as many as 40,000 tickets were sold.6 According to the Boston Globe, the fans were a sight to behold: “It was a magnificent crowd, a typical football crowd. There were the furcoated men and women, the college youth with the greatest thing in style and cover on their overcoats; there were young women and matrons in resplendently bright headdresses.”7 Cardinal O’Connell and VIPs from the Boston Archdiocese presided over the game in a box overlooking the 50-yard line.

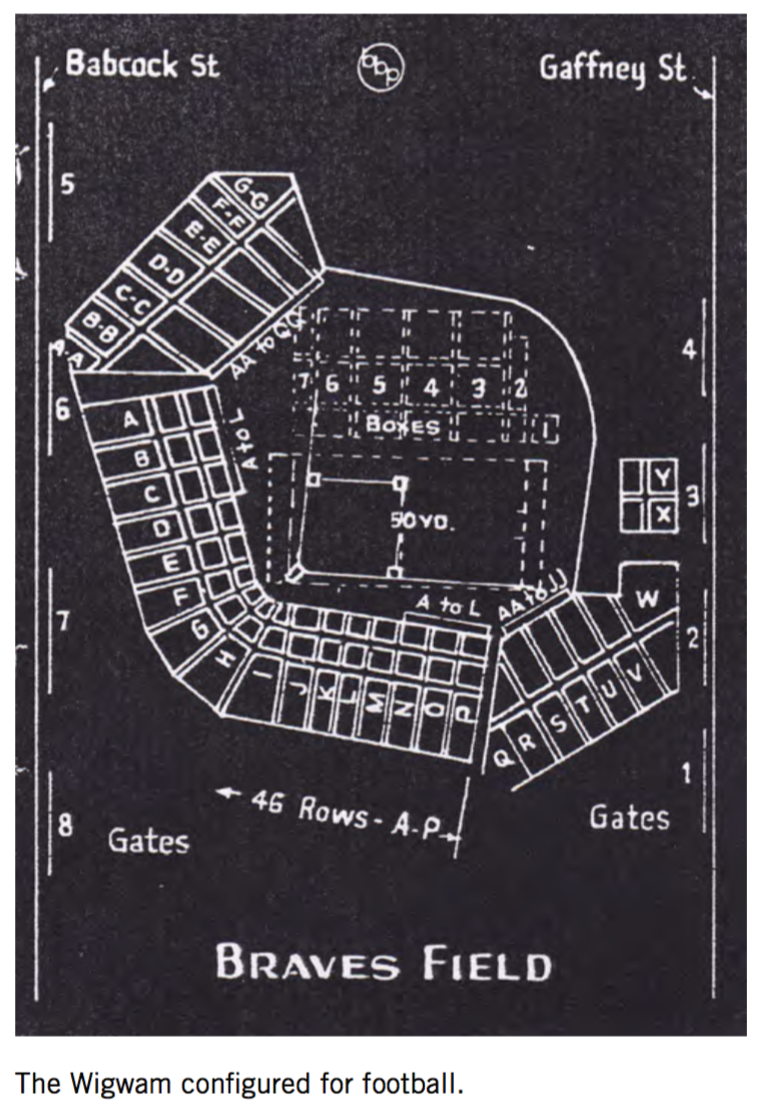

There were many complaints about Braves Field as a setting. The field was never completely football-friendly. Braves Field’s shape, designed for baseball, created blind spots for spectators. Harvard Stadium’s horseshoe, in comparison, allowed more fans to clearly see how each play developed. At Braves Field, a large number of seats were located in the end zones and many attendees were forced to stand on the sidelines.

On the day of the game, the field was a wet, slippery quagmire of ooze. The game resembled a large mud-wrestling match.

The big difference in the game was kicking. The first crucial sequence of plays occurred midway through the first period. After the Eagles were stopped at their own 44-yard line, a BC punt landed Holy Cross on its own 12-yard line. Two short runs convinced the Purple’s coach that the best course of action would be a quick kick. But a fumbled snap cost the Crusaders 10 yards. With fourth and long at the 5, Holy Cross was forced to punt the ball from its own end zone. The punter slipped and the ball hit the goalpost. Holy Cross won the scrum for the ball and made the recovery in the end zone but BC had the safety and a 2-0 lead.

In the second quarter Boston College had three consecutive opportunities inside its opponent’s 20-yard line but came up empty-handed as the Holy Cross defense held. But the kicking game again let the Crusaders down late in the first half. Boston College’s substitute punter, Corrigan, placed a perfect coffin-corner kick at Holy Cross’s 2½ yard line. Holy Cross’s coach decided to punt instead of run and leave the game in the hands of the defense. A shanked punt ruined that strategy and gave BC first and goal at the 5-yard line. Ben Roderick powered the ball over the Eagles’ right side for the game’s first touchdown. BC missed the point after but held an 8-0 lead at halftime. The Purple had a touchdown disallowed early in the third quarter. A Boston College punt returner fumbled a ball and Chick Gagnon returned it for a touchdown. However, the ball was called dead because a Crusader kicked the ball before taking possession.8

The final score of the game came late in the fourth quarter. Holy Cross muffed a punt return and the Eagles recovered it at the Holy Cross 6-yard line. Jimmie Liston ran the ball straight up the middle to give BC a 12-0 victory.

The Eagles had 178 yards rushing and 57 passing yards. They benefited from a 17-yard pass interference penalty. Holy Cross rushed for 130 yards and completed 5 of 15 passes for 57 yards.

The teams made $20,000 apiece for the game which, in today’s dollars, translates to $250,000.9 At the time, it was the largest football crowd in each school’s and in Boston’s history, but just two years later, the 1922 game at Braves Field attracted 54,000 – a record unbroken as of 2014. The game was a breakthrough for both teams’ national ambitions as football powers. Games against national powers replaced local schools on their schedules. Eagles fundraising material featured the football team as a selling point. BC was invited to play Baylor in the Cotton Bowl’s inaugural game in 1922. In 1925 Holy Cross finally defeated Harvard. For Holy Cross and Boston College, this game was a beginning of glorious and profitable days in big-time football. And by the way, the 1920 Boston College football team was the first to be referred to as the Eagles.

This article appeared in “Braves Field: Memorable Moments at Boston’s Lost Diamond” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and Bob Brady. To read more articles from this book, click here.

Sources

The Boston Globe devoted several pages to coverage of the game. It was a primary source along with the New York Times and The Heights, Boston College’s student newspaper. The Boston College and Holy Cross media guides and websites were consulted for background information. The national weekly AP football poll wasn’t started until 1936. But a fan named James Vautravers went through the time and trouble to figure out who the top 25 teams would be if there was a national poll. His site, TipTop25.com, is authoritative as a source for figuring out the strongest pre-1936 college football teams. According to their strength of schedule and wins, BC would have been ranked number 11 and Holy Cross number 23 in TipTop’s hypothetical polls. The teams’ opponents, Harvard and Yale were respectively ranked 2 and 16.

Boston College’s library’s virtual exhibit, bc.edu/libraries/about/exhibits/burnsvirtual/teams/3.html, has pictures and information about the 1920 team.

Notes

1 “Cardinal O’Connell sees B.C. Gridders in Practice,” Boston Daily Globe, November 30, 1920, 11.

2 “Mr. Daniel J. Coakley Makes Donation of $1,000 to the Athletic Association,” The Heights, Volume II, Number 3, October 15, 1920, 1.

3 “College Football Teams of the Eastern Section as Ranked for the 1920 Season by The New York Times,” New York Times, December 5, 1920, 114.

4 “B.C. Team One of the Best Says Charley Brickley,”Boston Daily Globe, December 4, 1920, 6.

5 Melville E. Webb Jr., “Rivals Ready for the Big Game: Fitzpatrick out of the Boston College Lineup,” Boston Daily Globe, December 4, 1920, 1 and 6.

6 “Cardinal O’Connell Sees B.C. Gridders in Practice,” Boston Daily Globe, November 30, 1920, 11.

7 “Wonder Crowd Throngs Field: Battle in Mud is Seen by at Least 30,000,” Boston Daily Globe, December 5, 1920, 18.

8 Melville E. Webb Jr., “Boston College Winds Up With 14-0 Victory,” Boston Daily Globe, December 3, 1920, 1, 18-19.

9 “B.C.-Holy Cross Contract for Three Years Signed,” Boston Daily Globe, December 15, 1920, 17.

Additional Stats

Boston College 14

Holy Cross 0

Braves Field

Boston, MA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.