July 20, 1894: Beaneaters blast Giants in first game at South End Grounds after fire

The Boston-New York baseball rivalry did not originate with the Red Sox and the Yankees clashing in American League contests. Diamond hostilities between the two cities predate the birth of the junior circuit. Heading into play on this July 1894 day in Boston, the 12-team National League clearly had an upper quartile in a trio of teams that all played better than .600 ball. The first-place Baltimore Orioles led the way, trailed closely by the second-place Beaneaters and the third-place New York Giants.

The Boston-New York baseball rivalry did not originate with the Red Sox and the Yankees clashing in American League contests. Diamond hostilities between the two cities predate the birth of the junior circuit. Heading into play on this July 1894 day in Boston, the 12-team National League clearly had an upper quartile in a trio of teams that all played better than .600 ball. The first-place Baltimore Orioles led the way, trailed closely by the second-place Beaneaters and the third-place New York Giants.

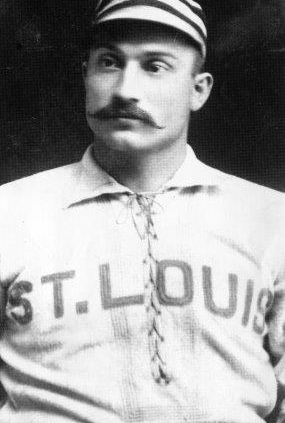

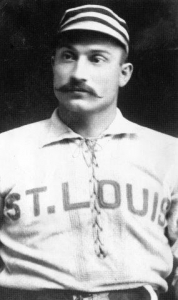

The mound matchup appeared compelling with two star pitchers at the height of their prowess. Both regularly won at least 20 games. For the home team, Jack Stivetts took the hill. In his rookie season, he led the American Association with a 2.25 ERA. From 1890 through 1893, Stivetts won 27, 33, 35, and 20 games for the Association’s Browns and the Beaneaters. Those impressive stats, however, seemed somewhat small when compared with those of his mound opponent, Amos Rusie, the Hoosier Thunderbolt. For New York from 1890 through 1893, Rusie won 29, 33, 32, and 33 games, or 12 more than Stivetts did over the same span. But the old hoodoo appeared to afflict Rusie when he pitched against the club from the Hub. Noted the Boston Globe, “He has won just one game from Boston since he has been with New York. Luck is dead against the big pitcher against the Beaneaters.”1

And on this particular day, the Beaneaters had an unusual home-field advantage that might have inspired them. A bit more than two months earlier, the South End Grounds was destroyed in a fire “started by a cigar or cigarette dropped among old peanut shells”2 during a Baltimore-Boston game, when Boston’s Tommy Tucker and Baltimore’s John McGraw … got into a savage fight … after Tucker slid hard into third base and McGraw kicked him in the face. … The conflagration in its initial stages could easily have been stomped out, but it was ignored by the crowd – who were caught up in the fracas on the field and its aftermath – until the end of the inning.”3

The faithful Boston fans eagerly returned to their old stamping grounds, renovated after the fire, “and a large crowd turned out to greet them,” noted the New York Times. “The heat was so intense that the cozy little grand stand, with a seating capacity of only 900, was totally inadequate to accommodate those who wished to witness the game from a sheltered position.”4

Even against a pitcher as imposing as Rusie, the bats of the Beaneaters soon proved as hot as the weather. The Hoosier Thunderbolt looked sharp early, wrote the estimable baseball scribe Tim Murnane: “It is doubtful whether Amos Rusie ever had greater speed, and the way he shot the ball through space … in the first inning made it seem impossible for any man to meet the ball with anything like accuracy.”5

Boston’s half of the second inning made this notion seem preposterous. Tucker singled. Jimmy Bannon singled. Billy Nash hit a three-run homer to put the Beaneaters up 3-0. Backup catcher Jack Ryan singled and scored on a triple by Stivetts that gave him a 4-0 lead. A multitalented player who appeared at every position other than catcher over the course of his 11-year career, Stivetts would slash his way to a .328/.369/.533 season in 1894 and smack seven triples.

Bobby Lowe plated his pitcher with a groundball to New York’s Shorty Fuller, who made a throwing error that made the score 5-0 and placed Lowe on second. At 5-feet-6, Fuller today seems less exceptional for his lack of height than for the frequency of his miscues. (He made 73 in 1894, a substantial total but far short of the career-high 92 he made in 1892, his first season in New York.) Herman Long doubled Lowe home to put Boston up 6-0. Hugh Duffy, who would hit .440 in 1894, singled. Long and Duffy both scored, too, the latter on errors on the same play by Rusie overthrowing second and George Van Haltren doing the same with his return heave to George Davis at third base. The Beaneaters had tallied eight runs in the inning thanks to a bounty of Boston hits and a trio of errors by the Giants.

A bad day for New York got worse in the fourth inning when the Giants had runners on first and second and what looked like a single became instead a rare 7-4-5 double play. Tommy McCarthy in left field charged a liner and whipped it to Lowe for a force out at second base. Lowe relayed the ball to Nash at third who tagged out the runner from second. Murnane marveled, “It would be impossible to make a more daring and yet brilliant play on a ball field.”6

Duffy, who in addition to his amazing batting average would lead the National League in 1894 with a career-high 18 homers, smashed a round-tripper in the fourth to put Boston up 9-0. Known as the Heavenly Twins, McCarthy and Duffy put on a celestial performance both at the plate and in the field.

Heaven could wait in the seventh when Duffy appeared to throw out New York player-manager John Montgomery Ward at third base. Nash’s error attempting to apply the tag let the ball get away and enabled Ward to score an unearned run. Even though the move paid off, manager Ward should have chastised player Ward for his overly aggressive baserunning given the large deficit his team faced.

The Beaneaters got that run back plus two more in the seventh to make the final score 12-1. The rally consisted of McCarthy’s triple, doubles by Tucker and Bannon, and, atoning immediately for his error, an RBI single by Nash.

In spite of the rout, both pitchers hurled complete games (amazingly, only five pitchers appeared for the Giants in 1894, when Rusie finished second in the NL with 444 innings pitched). While the more renowned Rusie got rocked, Stivetts superbly pitched a seven-hitter, a feat especially impressive in the offensively charged 1894 season, when the National League as a whole had a .309 batting average, and its teams averaged 7.4 runs per game. “Jack Stivetts,” the Globe commented, “pitched a game … that would win every time.”7

Beating New York always makes Boston fans feel grateful; doing so during the first game back at a beloved ballfield made an easy victory even more gratifying than usual.

Notes

1 “Echoes of the Game,” Boston Globe, July 21, 1894: 2.

2 Harold Kaese, The Boston Braves, 1871-1953 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2004), 67.

3 David Nemec, “Tommy Tucker,” sabr.org/bioproj/person/c54e887d (accessed August 8, 2017).

4 “Giants Badly Beaten,” New York Times, July 21, 1894.

5 T.H. Murnane, “Bat Like Fiends,” Boston Globe, July 21, 1894: 2. The descriptions of the plays in this game derive from Murnane’s detailed account.

6 Murnane. The Times described the play thusly: “McCarthy worked his trap-ball trick when New York had a good chance to score in the fourth inning, and retired the side.”

7 “Baseball Notes,” Boston Globe, July 21, 1894: 2.

Additional Stats

Boston Beaneaters 12

New York Giants 1

South End Grounds

Boston, MA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.