July 29, 1947: The West wins another Negro League East-West Game at Polo Grounds

The East-West All-Star Game was the highlight of the Negro Leagues’ season, bigger even than the Negro World Series. Begun in 1933 at the Chicago White Sox’ Comiskey Park, in the same year as the All-Star Game in the then-segregated White major leagues, the Black game regularly outdrew its counterpart during World War II, when the Negro Leagues had their best-attended and most profitable years.1 In the beginning, the single Black league, the Negro National, divided its clubs into Eastern and Western groups to pick two sets of all-stars, giving the game its name. Starting in 1937, the formation of the Negro American League in the Midwest and South enabled it to provide the West’s roster, while the Negro National supplied the East’s players.

The East-West All-Star Game was the highlight of the Negro Leagues’ season, bigger even than the Negro World Series. Begun in 1933 at the Chicago White Sox’ Comiskey Park, in the same year as the All-Star Game in the then-segregated White major leagues, the Black game regularly outdrew its counterpart during World War II, when the Negro Leagues had their best-attended and most profitable years.1 In the beginning, the single Black league, the Negro National, divided its clubs into Eastern and Western groups to pick two sets of all-stars, giving the game its name. Starting in 1937, the formation of the Negro American League in the Midwest and South enabled it to provide the West’s roster, while the Negro National supplied the East’s players.

The overwhelming popularity of the East-West game among Negro League fans in Chicago led to the playing of a second contest some years in a more Eastern location, designed to give fans in those cities a chance to see the stars, too. The Eastern game in 1947 was played at night on July 29 at the New York Giants’ Polo Grounds in New York, two days after the West’s 5-2 win over the East at Comiskey Park.

It proved to be the most popular by far of the games outside Comiskey, with an announced attendance of 38,402. The East aimed to reverse the dominance of the West, which had won five of the past six games, but this game would be no different. The West won decisively, 8-2.

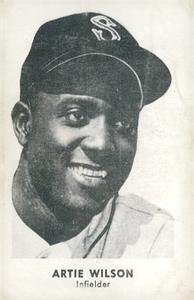

The East, though, jumped out to a 2-1 first-inning lead, scoring all the runs they would manage. The West’s run was unearned, although East starting pitcher Rufus Lewis of the Newark Eagles deserved most of the credit for it, anyway. He walked the leadoff hitter, shortstop Artie Wilson of the Birmingham Black Barons, and sent Wilson to second on a wild pickoff try. One out later, center fielder Sam Jethroe of the Cleveland Buckeyes singled to center to drive him in.

The East struck against the Kansas City Monarchs’ Ford Smith with two outs in the bottom of the inning. First baseman Johnny Washington of the Baltimore Elite Giants beat out an infield hit and left fielder Monte Irvin of Newark singled. Both scored when second baseman Silvio Garcia of the New York Cubans lined a double to left.

Lewis, who pitched the first three innings for the East, gave up two runs in the third to put the West ahead to stay. Wilson again led off by getting on base, this time with a single. A sacrifice and another out moved him to third. Second baseman Piper Davis of Birmingham drove Wilson in with a single, and circled the bases when Henry Kimbro of the Elites, the East’s center fielder, let the ball get by him and roll to the wall for a three-base error. The West led, 3-2.

The American Leaguers scored three more times in the fifth inning off Luis Tiant of the Cubans. Wilson again led off with a single. He stole second, got to third on an out, and scored easily when Jethroe tripled off the left-field wall. Jethroe scored on Davis’s infield out. The Indianapolis Clowns’ Ray Neil, a pinch-hitter, doubled and left fielder José Colás of the Memphis Red Sox scored him with a single, pushing the lead to 6-2.

The third East pitcher, Joe Black of Baltimore, gave up the final two West runs in the top of the eighth. With one out, catcher Quincy Trouppe of the Buckeyes singled and went to third when Wilson again singled. Wilson stole his second base of the game to put both runners in scoring position for Jethroe, who knocked them both in with a single.

The East, meanwhile, despite getting eight hits and nine walks off West pitchers, hit into three double plays, and left 12 men on base. Their most frustrating inning was the sixth, when consecutive singles by two Elite Giants, pinch-hitter Bob Romby and Black, followed by a walk to Kimbro loaded the bases with no one out against the Clowns’ Johnny Williams. West manager Frank Duncan called Memphis’s Spoon Carter in to relieve, and Carter induced a home-to-first double-play grounder and a fly out to squash the East’s rally.

Wilson, who had four singles and a walk, scored four runs, and was never retired all night, and Jethroe, who drove in four runs with three hits, were the batting stars of the evening. Washington had two hits for the East. Smith, who pitched the first three innings for the West, was the winning pitcher, and Lewis, who went three as the East starter, took the loss.

This game was the fourth of five “extra” East-West games (the others were in 1939, 1942, 1946, and 1948). In contrast to the Chicago game, which could almost always count on attendance of more than 40,000, and which had an attendance of 48,112 two days before the Polo Grounds game, the Eastern games did not draw nearly as well.

This evening in New York, though, was a major exception. The gate revenues of $44,495.55 produced a net profit of $18,864.54 after all expenses. The net was split evenly between the two leagues, which in turn divided their shares among the six teams in each league. The not-quite $1,600 each team received was a lot by Negro League standards.

This was particularly so considering that it was the second such windfall of 1947 – the teams each received about $1,800 from the Chicago game.2 To put this into Negro League perspective, the Newark Eagles’ combined shares of $3,400 would have covered about 15 percent of the team’s entire payroll, just for the loan of three players to the East roster – Irvin for two games and Lewis and Max Manning, the Chicago game starter, for one each.3

The 38,402 who saw the game probably constituted the largest East Coast turnout ever for a Negro League game. The usual Eastern attendance leader for Black games was Yankee Stadium, but attendance there never topped the 30,000 or so who would come to see Satchel Paige pitch in the 1940s.4

The New York Amsterdam News Black weekly quoted Cubans owner Alex Pompez, whose team made the Polo Grounds its home park and who was the chairman of the game committee, as predicting a crowd of 40,000. Trying to call sporting-event attendance ahead of time can be perilous, but Alex was nearly spot on. “Who was it said New York is not a baseball town?” he boasted.5

Dan Burley, covering the game for the Amsterdam News, described “a colorful, gay and happy throng that started the trek to the Polo Grounds as early as six o’clock.” Burley attributed the size of the crowd in part to “the fact that Primary Election Day closed all taverns and liquor stores from 3 until 10 P.M. and the thousands who might otherwise have been content to hang around their favorite joints, came out to the ball game in person.”6

Maybe some fans came out to check out possible future stars of the now-integrated major leagues. At least one, and maybe more, definitely did so. Louis Effrat, covering the game for the New York Times, spotted Ed Holly, a Chicago Cubs scout, in the stands. Holly, though, was noncommittal about future signings.7 He and any of his other colleagues who were there got a good glimpse of the future, though. Of the 32 players in both lineups, nine went on to the integrated majors, and 11 more topped out in the minors.

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Kurt Blumenau and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to using the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted the Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org websites for pertinent material and the box score noted below, as well as game stories in the New York Daily News (“Negro AL Rips NL Stars,” July 30, 1947: 59) and Chicago Defender (“West Again Beats East; This Time, 8-2,” August 9, 1947: 11).

https://retrosheet.org/NegroLeagues/boxesetc/1947/B07290ASE1947.htm

Notes

1 For example, according to Retrosheet.org, in 1942 the East-West game outdrew the All-Star Game, 48,400 to 34,178; in 1943 51,723 to 31,938; in 1944 46,247 to 29,598; in 1946, 45,747 to 34,908, and in 1947, 48,112 to 41,123. There was no All-Star Game in 1945 due to wartime travel restrictions, but the East-West Game was played, and drew a subpar crowd of 31,714.

2 Financial accounting for “Negro National League and Negro American League, East West Game, Chicago, Ill July 27, 1947”; Financial accounting for “Negro National League and Negro American League, All Star Game, July 29, 1947 Polo Grounds, New York, N.Y.” Newark Business Papers, Newark (New Jersey) Public Library. The profits for the Chicago game were significantly greater than in New York due to higher ticket prices.

3 Newark Eagles Business Papers, Newark Public Library.

4 James Overmyer, Table of “Black Games at Yankee Stadium, 1930-1948,” in “Black Baseball at Yankee Stadium: The House that Ruth Built and Satchel Furnished (with Fans),” Black Ball: A Negro Leagues Journal, Vol. 7, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2014), 20-28. Also published in John Graf, ed., From Rube to Robinson: SABR’s Best Articles on Black Baseball (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2020).

5 “Expect 40,000 at ‘Dream Game,’” New York Amsterdam News, July 26, 1947: 10.

6 Dan Burley, “86,514 See 2 Negro Baseball Classics,” New York Amsterdam News, August 2, 1947: 1.

7 Louis Effrat, “Negro Star Game to American Loop,” New York Times, July 30, 1947: 24.

Additional Stats

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.