June 15, 1869: A cunning play saves Cincinnati’s streak

Tuesday dawned gray and damp in New York City. But the sun broke through in the early afternoon, warming the streets and the spirits of the sporting public, which had long anticipated the day’s match between the reigning champions of baseball, the Mutuals of New York, and the interlopers from the West, the Cincinnati Red Stockings.

Tuesday dawned gray and damp in New York City. But the sun broke through in the early afternoon, warming the streets and the spirits of the sporting public, which had long anticipated the day’s match between the reigning champions of baseball, the Mutuals of New York, and the interlopers from the West, the Cincinnati Red Stockings.

The Red Stockings, the best club west of the Alleghenies, had still to prove their mettle against the powerhouse clubs of the East. The 1868 Red Stockings compiled a 36–7 mark, but all their losses came against clubs from Philadelphia, Washington, and New York. After the National Association of Base Ball Players changed its rules to permit professionalism, the leadership of the Cincinnati Base Ball Club decided to employ an all-salaried nine for the 1869 season, with the expressed hope of being able to defeat the top Eastern clubs. No other team took up the mantle of professionalism in 1869, thus making the Red Stockings the first professional nine, all players under contract with a stipulated salary (and in turn required to pledge themselves to temperance).

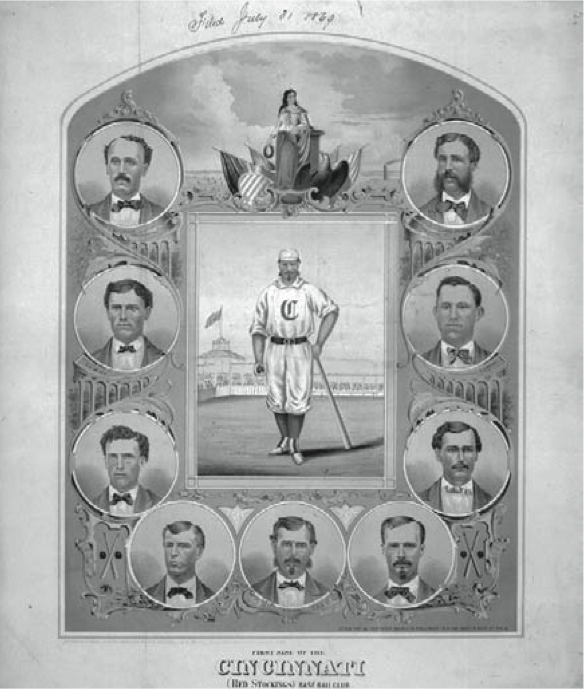

The Red Stockings signed several top players, including George Wright, the younger brother of Red Stockings captain Harry Wright. George was the best shortstop in America, and the strongest batsman: the 19th-century version of Honus Wagner. In addition the Red Stockings featured veteran pitcher Asa Brainard; Fred Waterman, the leading third baseman in the country and the only Cincinnatian on the squad; first baseman Charles Gould; and one unproven youngster, 20-year-old right fielder Cal McVey. At 34, Harry Wright was the established leader, a respected captain, the center fielder and the primary relief pitcher.

The Red Stockings had begun their monthlong tour of the East on May 31, and won their first 10 matches before arriving in New York City. Although this was just one game held in the early weeks of the season, it drew the kind of attention one would see today for a postseason game. In part this was because teams did not play each other that often, and this was especially true of a team from as far away as Cincinnati. This was likely to be the only visit the Red Stockings would make to New York, perhaps the only time they would play the Mutuals, unless the Mutuals traveled west (which they did late in the season, but that game had not been scheduled as of June). The game also drew considerable betting interest. “Thousands of dollars” had been wagered on the game, estimated one writer.

At 1:30 P.M., a contingent of Mutual club officials called on the Red Stockings at their hotel and escorted them to the ballpark in elegant carriages. The game was played on the Union Grounds, a large enclosed field in Brooklyn: “The grounds are beautiful, being sodded all over, grass short,” wrote a Cincinnati correspondent. “Flags of all nations were floating to the breeze from jackstaffs on different club-houses, and the scene was one of brilliancy.” The attendance, diminished by the gray weather, was estimated at 4,000–7,000.

The Mutuals featured several established stars, including outfielder John Hatfield, who had played for the Red Stockings in 1868. Hatfield had signed with Cincinnati for 1869, but also signed with the Mutuals, and he was dismissed from the Red Stockings for this duplicity. His conduct so irritated the decorous Harry Wright that Wright still held a grudge on the eve of the match. He urged his team to not only beat the Mutuals, but in particular to keep Hatfield from scoring a run.

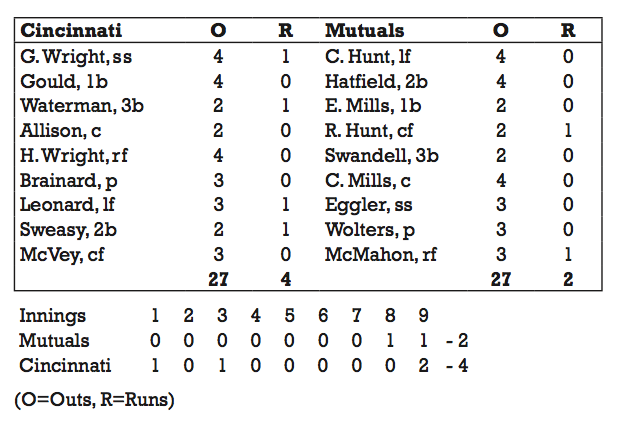

The Red Stockings won the toss and chose to bat last. Back in Cincinnati, baseball enthusiasts gathered around newspaper offices and other establishments that posted regular bulletins on the game’s progress. The Red Stockings scored single runs in the first and third innings. But the bulletins seemed to be in error for the Mutuals. In this high-scoring era of rough fields, no gloves, and heavy hitting, teams usually tallied dozens of runs. But on this day the bulletins came in with zero after zero for the Mutuals. Brainard’s pitching and sure fielding by the Red Stockings held them scoreless for the first seven innings. Other than their two early runs, the Cincinnati boys were whitewashed as well by the New York pitcher, Wolters.

The Mutuals finally broke through in the eighth with one run. Then they scored the tying run in the ninth and seemed poised for more with runners on first and second and none out. But third baseman Waterman and shortstop Wright pulled off a clever play. Waterman deliberately dropped a fly ball (no infield-fly rule then) and threw to Wright, who had anticipated Waterman’s play and rushed to cover third. Wright then threw to second to complete a threat-ending 5-6-4 double play.

With one out in the bottom of the ninth, the Mutual third baseman made a wild throw on Brainard’s liner, and Asa wound up on third. He scored moments later on a passed ball, and the victory was the Reds’. The crowd broke onto the field, but the rules of the day required the inning to be played out in full. Once order was restored, Cincinnati scored one more tally, making the final score 4–2.

The game was immediately hailed as the greatest ever played. The crisp play of both teams and the novelty of the low score marked it as truly memorable. “The best played game on record,” said the New York World. “The most remarkable game on record,” gushed the Sun. The Cincinnati Gazette reporter sent home this dispatch: “We are tossing our hats tonight and shaking each other by the hand. We are the lions … because we have beaten the Mutuals, and because the game was the toughest, closest, most brilliant, most exciting in base ball annals.”

And for Harry Wright, it was especially sweet. The duplicitous John Hatfield did not get a hit, and did not score a run.

Telegrams awaited the boys when they returned to their hotel, including this from “The Citizens of Cincinnati”: “The streets are full of people, who give cheer after cheer for their pet club. Go on with the noble work. Our expectations have been met.” The noble work continued. The Red Stockings completed their conquest of New York clubs the next two days with victories over the Atlantics and Eckfords, then swept the Philadelphia and Washington nines and returned to the Queen City on July 1 having won all 20 games on the Eastern tour.

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Additional Stats

Cincinnati Red Stockings 4

Mutuals of New York 2

Union Grounds

Brooklyn, NY

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.