June 15, 1948: ‘Look at your wonderful lights here’: Tigers win first night game in Detroit

Walter O. Briggs was definitely old school.

Walter O. Briggs was definitely old school.

As the owner of the Detroit Tigers, he had long believed that the national pastime was meant to be played in the daytime. “Baseball belongs to the sun and the sun to baseball,” he argued.1

But the national pastime was entering a new era. Ever since May 24, 1935, when Cincinnati’s Crosley Field hosted the first major-league contest under the stars, more and more ballparks were erecting light towers.

By the beginning of the 1948 season, the Tigers remained the last bastion of daytime-only baseball in the American League. That changed on June 15, when the Bengals finally played the first night game at Briggs Stadium (That left Wrigley Field in Chicago as the only remaining major-league park without lights.)

Many baseball fans may wonder why it had taken the Tigers so long. The primary reason, of course, was Briggs himself. And even though his son, Walter “Spike” Briggs Jr., who was a member of the front office, encouraged his father to install lights as early as 1936, the elder Briggs resisted.

It should be noted, however, that the senior Briggs had indeed consented to install light towers for the 1942 season, and had even placed an order for the steel. But when the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, dragged the United States into World War II, Briggs canceled the order and the steel was used for the war effort. Some of those close to Briggs said that he was pleased not to have to go through with the installation.

Three years after the war ended, however, Briggs had a change of heart, and realized that his namesake ballpark would have to enter the modern age. In other cities, night baseball had opened up a whole new customer base. It allowed the workingman to head down to the ballpark after his day at the office (or the factory) was done. Briggs was forced to admit that night baseball made economic sense.

He insisted on the best lighting system available, which included eight 150-foot-high light towers with a total of 1,386 bulbs. The cost was slightly more than $400,000. On May 10, 1948, the press was invited to a test run. Briggs, wheelchair-bound as a result of polio, threw the switch to light up the grand ballpark. To demonstrate how bright it was, groundskeeper Neil Conway sat at second base, reading a newspaper.

Six weeks later, the highly anticipated night arrived at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull. The gates were opened at 6:00. The Tigers, managed by Steve O’Neill, took batting practice from 7:15 to 8:00, while Connie Mack’s visiting Philadelphia Athletics did so from 8:00 to 8:30. The evening was chilly, only 59 degrees at game time. “It’s a coffee night,” said Charlie Jacobs, a concessionaire, “nothing much but coffee. Too cold for anything else.”2

It had been decided to wait until it was nearly fully dark before turning on the lights, thus allowing them to take full effect. When the switch was flipped at exactly 9:29, the bright bulbs flooded the green field with a dazzling glow, and the crowd of 54,480 let out a collective cry of wonder.

And then the game commenced.

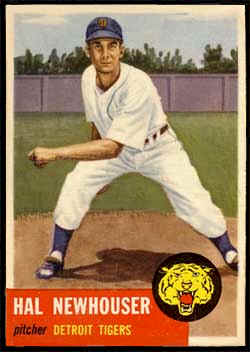

A’s shortstop Eddie Joost led off by drawing a base on balls from Detroit native Hal Newhouser. At 27, the left-handed Newhouser already had 138 big-league wins and two Most Valuable Player awards under his belt. He retired the next two A’s, and then walked Ferris Fain to move Joost into scoring position. A double by Hank Majeski gave Philadelphia a 1-0 lead.

Newhouser remained shaky in the top of the third as he walked the first two batters. But a double play and a groundout saved the Tigers from further damage.

In the bottom of the third the Tigers tallied two runs on three walks and a single by Hoot Evers. Newhouser, meanwhile, found his groove and allowed only one hit and two walks the rest of the way.

Detroit padded its precarious 2-1 lead in the bottom of the eighth when Dick Wakefield and Pat Mullin each hit a solo home run to close out the scoring at 4-1.

In pitching his eighth complete game of the season, Newhouser gave up only two hits, walked six, and struck out five to lower his ERA to 2.98. It was his seventh consecutive victory. A’s starter Joe Coleman, who also went the distance, saw his record drop to 7-3, despite a solid effort.

Detroit won its fifth game in a row to improve to 27-25 and remained in fourth place, seven games out of first. The second-place A’s, three games off the pace, fell to 31-21.

From his box seat behind third base, American League President Will Harridge gave his stamp of approval of the scene. “This is the best lighted park of them all,” he testified at 10:49 P.M. “It sets a new standard for night baseball.”3

And what about the 84-year-old Mack, who had managed the A’s since 1901 and had played in his first big-league game in 1886, not long after Thomas Edison began toying around with his first incandescent light bulb in his Menlo Park laboratory? “Look at your wonderful lights here at Briggs Stadium,” Mack exclaimed. “It makes it just like day in your beautiful park. And what a beautiful park! Briggs Stadium is the finest park in baseball.”4

Others, however, were more skeptical. Said George Kell, the Tigers’ All-Star third baseman, “I’m an afternoon ballplayer. Playing at night seems like a carnival or a sideshow.”5

One fan in attendance, who had seen his first ballgame at old Bennett Park in the 1907 World Series, observed, “I think it’s much better than a day game. For my money, you can’t beat it.”6

Night games quickly proved to be a success in the Motor City. The Tigers played 14 games under the lights in 1948, with an average attendance of around 45,000, a significant increase over afternoon affairs.

That cool June evening in 1948 wasn’t the first time that baseball had been played under artificial lighting at Michigan and Trumbull. On September 24, 1896, when old Bennett Park still stood at the location, the Western League’s Tigers played a doubleheader exhibition against the National League’s Cincinnati Reds. Makeshift electric lights were originally scheduled to be strung up between games. With dusk approaching, however, and Detroit leading 13-4 after eight innings in the opener, the umpire halted the game in order to allow the lights to be hastily hung.

Details of the game have been lost to time, although one newspaper stated that the event was a financial success, with nearly 1,200 cranks on hand.

It took more than 50 years for another night game to be played at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull.

But it was worth the wait.

This article appeared in “Tigers By The Tale: Great Games at Michigan and Trumbull” (SABR, 2016), edited by Scott Ferkovich. To read more articles from this book, click here.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, Retrosheet.org and Baseball-Reference.com were also accessed.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/DET/DET194806150.shtml

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1948/B06150DET1948.htm

Bak, Richard, Charlie Vincent, and the Free Press Staff. The Corner: A Century of Memories at Michigan and Trumbull (Honoring a Detroit Legend) (New York: Triumph Books, 2000).

Enders, Eric, Ballparks Then and Now (San Diego: Thunder Bay Press, 2002).

Whitt, Alan, ed. They Earned Their Stripes: The Detroit Tigers All-Time Team (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, Inc., 2000).

Notes

1 Richard Bak, A Place For Summer: A Narrative History of Tiger Stadium (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1998), 215.

2 H.G. Salsinger, “The Umpire,” Detroit News, June 16, 1948.

3 Salsinger.

4 Leo Macdonnell, “Mostly Night Contests Predicted by Mack,” Detroit Times, June 16, 1948.

5 E.A. Batchelor Jr., “Tigers Like Night Games,” Detroit Times June 16, 1948.

6 Riley Murray, “Fans Roar Approval of New Lights,” Detroit Free Press June 16, 1948.

Additional Stats

Detroit Tigers 4

Philadelphia A’s 1

Briggs Stadium

Detroit, MI

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.