June 19, 1875: The ‘Model’ Game: Hartford vs. Chicago

The Chicago Tribune called it “The Most Brilliant Contest in the History of the Game.” Sportswriter Henry Chadwick, an ardent supporter of low-scoring “scientific” games, labeled it “the model game.” Other news reports called the June 19, 1875, contest between Hartford and Chicago the “most extraordinary” and “most remarkable” game ever played.

For years baseball games had been dominated by offense. From 1871–74 the average number of runs in a National Association game was 19. Double-digit scores were common. The 1875 season was different. That year the league batting average plunged nearly 20 points from the previous season and total runs per game were down to 12. The 1875 season also featured the first 1–0 game in history, won by Chicago over the St. Louis Red Stockings on May 11. Ten days later Hartford duplicated the feat, beating the New Mutuals of New York by the same score.

For years baseball games had been dominated by offense. From 1871–74 the average number of runs in a National Association game was 19. Double-digit scores were common. The 1875 season was different. That year the league batting average plunged nearly 20 points from the previous season and total runs per game were down to 12. The 1875 season also featured the first 1–0 game in history, won by Chicago over the St. Louis Red Stockings on May 11. Ten days later Hartford duplicated the feat, beating the New Mutuals of New York by the same score.

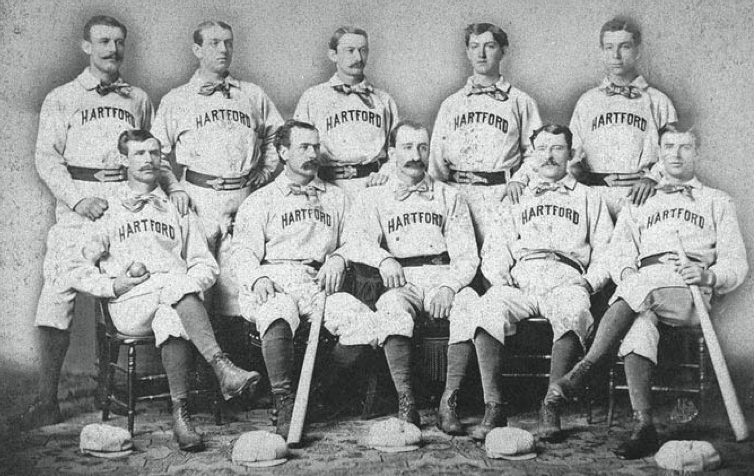

Although scoring was down, no one had witnessed a pitching duel like the one the 3,000 spectators at Chicago’s 23rd Street Grounds saw that Saturday afternoon. The drop in offense in 1875 was due in part to the growing prevalence of the curveball and Hartford had one of the first and best curveball pitchers in the box, William Arthur “Candy” Cummings. At the start of the year, the Hartford Post noted that Cummings “seems to have improved in his peculiar style of delivery over last year, and that wonderful curve will bother the heavy batters of opposing nines this year as it has before.” Veteran fastballer George Zettlein pitched for Chicago in this first meeting of the season between the two teams.

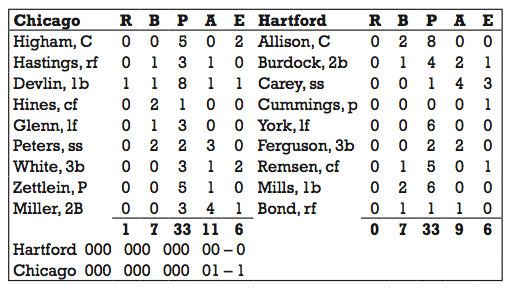

The game started unremarkably. Hartford and Chicago managed some baserunners—Hartford would leave seven men on base for the game, Chicago eight—but no runs crossed the plate. Hartford loaded the bases in the third inning but failed to score.

The Chicago crowd believed the slightly built Cummings (5-feet-9, 120 pounds) would falter against the bigger Zettlein, who outweighed him by 40 pounds. To their surprise, Cummings continued to shut out the White Stockings. Hartford nearly broke the scoreless streak in the eighth inning when, for the second time in the game, the visitors loaded the bases. But Chicago’s Scott Hastings, who had played for Hartford in 1874, saved the game with a great running catch in right field on a hit by Tom Carey. In an unprecedented development, the game remained scoreless through the entire nine innings. The two previous 1-0 games had both ended after nine innings.

The Chicago crowd was in a frenzy as the extra frames began. In the top of the tenth Hartford threatened again. An error and a hit put Jack Remsen on second base and Ev Mills on first with no outs. The end of the scoreless streak seemed imminent. Tommy Bond grounded to shortstop, where John Peters alertly threw to third to force out Remsen. Harmless infield popups by Doug Allison and Jack Burdock ended the threat. Chicago went down in order in the bottom of the 10th.

In the top of the 11th Cummings reached first on an error by Chicago first baseman Jim Devlin. Tommy York then stroked a hard-hit line drive to Peters at shortstop. He snared the ball and tagged Cummings to complete a double play.

Hastings opened the Chicago 11th with a single. Devlin then grounded to Bob Ferguson at third base for what looked like a sure double play. Fergy threw to second baseman Burdock for the force out, but when Burdock attempted to turn the double play, he threw wildly into the stands, allowing Devlin to scamper all the way to third base. Although no newspapers reported it, Cummings recalled in an interview with the Hartford Courant in 1913 that the throw actually hit Hastings as he ran from first to second, causing the ball to carom into the stands.

Hastings opened the Chicago 11th with a single. Devlin then grounded to Bob Ferguson at third base for what looked like a sure double play. Fergy threw to second baseman Burdock for the force out, but when Burdock attempted to turn the double play, he threw wildly into the stands, allowing Devlin to scamper all the way to third base. Although no newspapers reported it, Cummings recalled in an interview with the Hartford Courant in 1913 that the throw actually hit Hastings as he ran from first to second, causing the ball to carom into the stands.

With Devlin standing on third and only one out, the dangerous Paul Hines stepped to the plate. Hines would lead the White Stockings in batting in 1875 with a .328 average. Cummings later recalled, “The man at bat was a good hitter and I was trying my best to have him hit to center field. Instead the ball was hit to left and right away I knew it was all over. I ran behind the catcher to back him up, but knew it was useless, for the man in left field [Tom York], while he could throw home, invariably sent the ball far over the catcher’s head.” York caught the fly ball cleanly and Devlin broke from third. As Cummings had anticipated, the ball sailed over the catcher’s head, and Cummings gathered it in. “When at last Devlin galloped from third base across the home-plate every pair of lungs exerted themselves to the utmost, and stamping and clapping of hands were added to the vocal uproar,” the Chicago Tribune reported. As was the custom, the inning was finished with a base hit by Glenn and a fly out to right field by Peters.

Cummings, who later called this “the best game I ever pitched,” declared: “Had that run been shut off, there is no telling how long that game would have lasted.”

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Additional Stats

Chicago White Stockings 1

Hartford Dark Blues 0

At 23rd Street Grounds

Chicago, IL

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.