June 30, 1859: Caught on the fly: Knickerbockers vs. Excelsiors

In the May 29, 1859 issue of The Sunday Mercury, a weekly New York newspaper that extensively covered the expanding world of base ball playing, an untitled paragraph announced the possibility of a forthcoming game that would be strikingly different from all others played during the past few years: “We have heard it rumored — we do not know with what truth — that the Knickerbocker Club, of this city, will shortly play a match with the Excelsior Club, of Brooklyn, in which they will repudiate catching the ball upon the bound.” William Cauldwell, the editor of the newspaper, predicted that it would be “an interesting match, but no doubt somewhat tedious.”1 Nevertheless, on June 30, nearly 3,000 spectators gathered at the Elysian Fields in Hoboken, N.J., to watch what a New-York Times reporter characterized as an “experimental” game “to determine the relative merits of putting out men when fair struck balls were caught on the fly: as contrasted with the rule adopted by the Base Ball Convention, of allowing men to be put out when fair struck balls were caught either on the bound or fly.2

The conduct of such an experimental “fly” game had its impetus from a desire in the mid-1850s by the Knickerbockers to change the rules of the game “from the easy mode in which they have hitherto played it.”3 They were particularly uncomfortable with the “bound” out counted as an out any ball caught on one bounce.

The conduct of such an experimental “fly” game had its impetus from a desire in the mid-1850s by the Knickerbockers to change the rules of the game “from the easy mode in which they have hitherto played it.”3 They were particularly uncomfortable with the “bound” out counted as an out any ball caught on one bounce.

The desire to update the rules led to the holding of a convention of New York and Brooklyn ball clubs in Manhattan on Feb 25, 1857. The Knickerbockers proposed, according to the New York Clipper, abolishing the bound out in order to make the game “more manly and scientific.” Other players, particularly younger ones who had only begun playing in the mid-1850s, argued that such a rule change would make the game of base ball “too much like Cricket” and that balls caught on the fly rather than the bound “would hurt the hands more. A compromise proposed by the bound advocates was unanimously adopted. The bound out continued to be permitted under the proposed new rule: “[The striker is out] if a fair ball is struck, and the ball is caught either without having touched the ground or upon the first bound.” But as an inducement for players to attempt to catch the ball on the fly, the committee also proposed that “if a man was caught out before the ball touched the ground, that then the players who were running to the different bases, or home, could neither make an Ace nor Base, but had to return to their original position.”

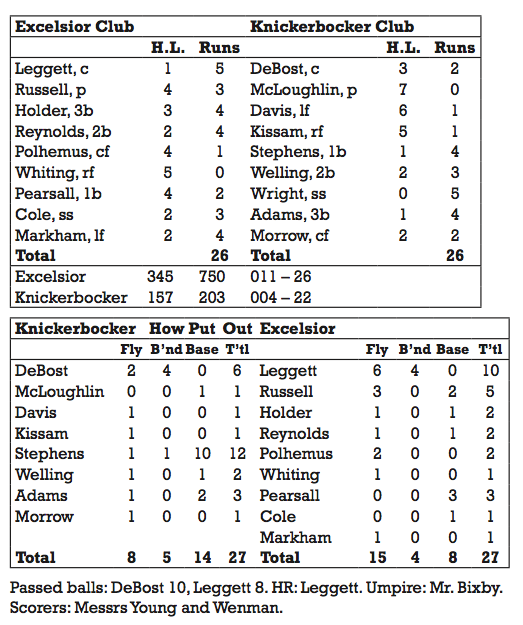

Although the Knickerbockers had failed to get the bound out excluded, they nevertheless forbade it during their intra-club practice games. In early 1859, they were finally able to persuade another club, the Excelsiors of South Brooklyn, “between whom and themselves the most cordial sentiments of friendship exists,” to play an experimental club-vs.-club game that excluded the bound out. The quality of play during the first half, which had the Excelsiors leading 24-15 after five innings, was sloppy. The Sunday Mercury reported that “There was some very bad fielding, and wild throwing on both sides, and on the part of some of the Knickerbocker members, a want of judgment in disposing of the ball, was plainly discernable.” The last was perhaps best epitomized in the second inning, when, with one out and runners on second and third, the Knicks’ right fielder Samuel Kissam caught a fly ball struck by Edwin Russell of the Excelsiors and, “apparently forgetting himself, sent the ball to third base, instead of second (which the lead runner had left and was bound to return to).”4 The lost out would have terminated the inning without the Excelsiors scoring a run. Instead subsequent strikes by John Holder, Thomas Reynolds, and Harry Ditmas Polhemus brought in four runs.

The fielding noticeably improved in the latter half, however, and the play moved along so crisply that the 26-22 Excelsior victory became the shortest on record in terms of time — two hours and ten minutes. But while conceding the game was “in spots” very interesting, especially a ninth-inning rally by the Knickerbockers, a skeptical Mercury reporter failed to discern any aspects of the game that would make him prefer the new “fly” system:

“We do not think that any balls were caught on the fly that would not have been so caught under the regular rules, but there were several balls lost, which might, perhaps, have been caught upon the bound; and one or two pretty catches were made upon the bound (one by Mr. [James Whyte] Davis) which, of course, did not count. Had the game been one governed by the regular rules of catching, our impression is that it would have been much more pleasing, and certainly shorter by several runs.5

In contrast, positive assessments of the “fly” game —probably written by Henry Chadwick — appeared nearly a week later in Porter’s Spirit of the Times and in the New York Clipper.6 The Porter’s account found that the experimental “fly” game

“was such as to satisfy any unprejudiced mind of the superiority, in every respect, of the [fly] method. In fact … but for the catch on the bound, which so often gives rise to a display in the field unworthy the efforts of the merest tyro, we should certainly claim for base-ball the merit of affording more frequent opportunities for brilliant fielding in one match, than can be had in a dozen cricket matches.”

Despite confident predictions in the Porter’s and Clipper accounts that the next convention of the National Association of Base Ball Players would surely eliminate the bound out, that action would not come to pass until December of 1864, when the thinning out of weaker and older clubs finally reduced sufficiently the conservative opposition to a rule change.7 In the meantime, however, other clubs, inspired by these experimental games, began testing and/or even regularly playing the “fly” game during the next few years.8

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Notes

1 “Out-Door Sports: Base Ball: Matches to Come Off,” Sunday Mercury, 29 May 1859, p. 5, col. 4. For previous discussions of the fly-vs.-bound debate, which extend the story through the eventual elimination of the bound out in 1864, see Warren Goldstein, Playing for Keeps: A History of Early Baseball (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1989), pp. 48-53; Andrew J. Schiff, “The Father of Baseball”: A Biography of Henry Chadwick (Jefferson, N.C. and London: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2008), pp. 51-58; and William J. Ryczek, Baseball’s First Inning: A History of the National Pastime Through the Civil War (Jefferson, N.C. and London: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2009), pp. 174-178.

2 “Base Ball: Excelsior Club, of South Brooklyn, versus Knickerbocker Club, of New-York,” New York Times, vol. 8, no. 2428 (1 Jul 1859), p. 4, col. 6.

3 “The Base Ball Convention and their New Rules,” New York Clipper, c. February 1857 clipping in Rankin scrapbook, Mears Collection, Cleveland Public Library.

4 “Out-Door Sports: Base Ball: The ‘Fly’ Game Between the Knickerbocker and Excelsior Clubs,” Sunday Mercury, 3 July 1859, p. 5, col. 4.

5 Ibid.

6 Both accounts, cited in the next two reference notes, used similar language to encourage the playing of a return game in Brooklyn. The account in Porter’s stated: “We hope that these clubs will afford our friends, on the other side of the river [i.e., in Brooklyn] an opportunity of judging of the merits of the catch-on-the-fly, by having a return match on the Excelsior grounds, which, in several respects, is favorably located for a fly game. Give us the return match, gentlemen, and as soon as you can.” The account in the Clipper stated: “We sincerely trust that these excellent clubs will, by a return match on the Excelsior grounds, give our Brooklyn friends an opportunity of witnessing the brilliant play the catch-on-the-fly rule admits of. Play a return by all means, gentlemen, and let us know when, that we may be there to witness a second triumph of our favorite play.” Chadwick became the Clipper’s chief baseball correspondent in June 1857. In at least one earlier instance he internally identified himself as the author of a game account in Porter’s. An account of a previous Knickerbocker-Excelsior game played on 8 July 1858 reported, regarding post-game activities, that “Our reporter—Mr. Chadwick—was called upon to respond to the toast of ‘The Press,’ but being somewhat diffident of his oratorical powers, he quietly retreated a moment before the call, having previously deputied the gentleman from the Tribune to respond, which duty he ably performed.” Significantly, this same account also included the observation that “The fielding of the Knickerbockers was marked by some excellent catches ‘on the fly.’ Their opponents seemed to prefer the surer, but less skillful method, of taking the ball on the first bound, a style of catching more suitable to juveniles we think ….” “Out-Door Sports: Base-Ball: Great Base-Ball Match in Brooklyn: Excelsior vs. Knickerbocker,” Porter’s Spirit of the Times, vol. 4, no. 20 (17 July 1858), p. 309, col. 1.

7 “Ball Play: The Base Ball Convention: the Fly Rule Adopted by a Large Majority,” New York Clipper, 23 December 1864.

8 Other early identified instances of “fly” games include Champion Jr. (NY) vs. Enterprise Jr. (Morrisania), 6 August and early October 1859; Knickerbocker (NY) vs. Empire (NY), 10 or 11 August 1859; Star (South Brooklyn) vs. Knickerbocker (NY), 13 September 1859; Manhattan vs. Oriental, 29 September or 6 October 1859; Excelsior (South Brooklyn) vs. Charter Oak (Brooklyn), 21 June 1860; America (South Brooklyn) vs. Twilight (South Brooklyn), 7 July 1860; Excelsior (South Brooklyn) vs. Putnam (Brooklyn, E.D.), 4 August 1860; Excelsior (South Brooklyn) vs. Knickerbocker (NY), 25 August 1860; Mohawk Jr. (Brooklyn) vs. Nassau Jr. (Brooklyn), 27 October 1860.

Additional Stats

Excelsiors of South Brooklyn

vs. Knickerbockers of New York

Elysian Fields

Hoboken, NJ

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.