May 1, 1959: Early Wynn homers late, throws one-hitter for White Sox

In December 1957 the Chicago White Sox and the Cleveland Indians got together for a headline-making trade. Popular Cuban-born outfielder Minnie Minoso was sent packing to the Tribe, along with utility infielder Fred Hatfield. For Minoso, a five-time All-Star who had turned 32 just days before the deal, it was a homecoming of sorts; he had played a handful of games with the Indians to begin his big-league career. Chicago, meanwhile, landed a couple of All-Stars, one young, the other not so much. Twenty-nine-year-old Al Smith could play all three outfield positions as well as third base. Smith (who had played with the Cleveland Buckeyes of the Negro American League in 1946-48) would bring his solid bat and athleticism to the Windy City. Joining him was another big name, an anchor on one of the greatest pitching staffs the game had ever seen.

In December 1957 the Chicago White Sox and the Cleveland Indians got together for a headline-making trade. Popular Cuban-born outfielder Minnie Minoso was sent packing to the Tribe, along with utility infielder Fred Hatfield. For Minoso, a five-time All-Star who had turned 32 just days before the deal, it was a homecoming of sorts; he had played a handful of games with the Indians to begin his big-league career. Chicago, meanwhile, landed a couple of All-Stars, one young, the other not so much. Twenty-nine-year-old Al Smith could play all three outfield positions as well as third base. Smith (who had played with the Cleveland Buckeyes of the Negro American League in 1946-48) would bring his solid bat and athleticism to the Windy City. Joining him was another big name, an anchor on one of the greatest pitching staffs the game had ever seen.

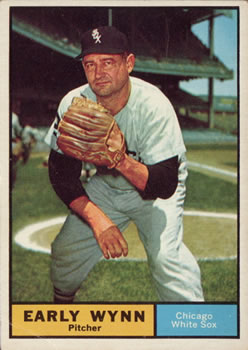

Early Wynn was a bulldog on the mound, a take-no-prisoners right-hander who did not hesitate to use the occasional brushback pitch if he felt it gave him an edge. Throughout his career, Wynn struggled with his control, which did not hurt his intimidation factor. He had been a promising, hard-throwing youngster with the lowly Washington Senators, but his fortunes changed when he was traded to the Indians after the 1948 season. In the early 1950s Cleveland abounded in great starting pitchers, but was a perennial bridesmaid to the powerhouse New York Yankees from 1951 to 1953. Finally, in 1954, under skipper Al Lopez, the Tribe won 111 games to capture the American League pennant by eight games over New York. Much of the success came on the strength of its five aces: Wynn (23 wins), Mike Garcia (19), Bob Lemon (23), Art Houtteman (15), and Bob Feller (13). But the Indians were swept by the New York Giants in the World Series.

Wynn won 20 or more games four times with Cleveland (1951, 1953, 1954, 1956). Nevertheless, at the time of his trade to the White Sox, he was fast approaching 38 years of age, coming off an unspectacular campaign in which he had won 14 and lost 17, with an unsightly 4.31 earned-run average. Despite his being reunited with Lopez, who was now skippering the White Sox, Wynn’s first summer in Comiskey Park in 1958 was more of the same: 14 wins, 16 losses, and a 4.13 ERA, although he made his fifth All-Star Game appearance.

On the bright side, the 1959 White Sox looked like a team heading in the right direction. After half a decade of being the third-best squad in the AL after New York and Cleveland, Chicago had finished a distant second behind the Yanks each of the previous two seasons. Creating a buzz on Chicago’s South Side was new owner Bill Veeck, an iconoclast known as much for his promotional genius as for his eye for talent. The White Sox did not have much offense. They featured solid pitching and fielding, however, and Lopez insisted to Veeck that the team was good enough to win. A lot hinged on what kind of contribution they could get from the geriatric Wynn.

Hoping for a comeback season, Wynn started 1959 well enough, with a complete-game victory against the Tigers in which he gave up only one earned run. He proceeded to get hit hard in his next three starts, including a dreadful game in Kansas City in which he gave up six earned runs in less than two innings to the doormat Athletics (but did not figure in the decision).

By May 1, Wynn’s ERA was 6.14. He was scheduled to face the Red Sox that evening at Comiskey. Boston would be without the services of slugger Ted Williams, who was recovering from a stiff neck suffered in spring training. Although they were playing under .500, the Red Sox lineup still featured Pete Runnels, Vic Wertz, Jackie Jensen, and Frank Malzone. They were no pushovers. Chicago, in second place with a record of 10-6, was only a game behind the Indians.

With one out in the top of the first inning, Wynn stepped off the mound and gestured toward his shortstop, Luis Aparicio. Only two days removed from his 23rd birthday, Aparicio was a slick-fielding Venezuelan, an All-Star in 1958, and one of the rising stars in the game. Apparently, Wynn wanted Aparicio to take a few steps to his right. The positioning struck Aparicio as odd, given that the left-handed-hitting Runnels was due up. A classic singles hitter, Runnels had a great eye at the plate. A two-time .300 hitter, he was also riding a hot bat.

Aparicio, against his better judgment, moved slightly to his right. Moments later, Runnels hit a sharp grounder that eluded Aparicio’s outstretched glove just to the left of the second-base bag. As the ball bounded into center field, Aparicio was convinced that had he not listened to Wynn, he would have gobbled up the ball and thrown Runnels out easily.

To the fans still shuffling in, it was just an innocuous-looking base knock. Wynn struck out the next batter, and White Sox catcher Sherm Lollar gunned down Runnels trying to steal second. Runnels’ seeing-eye single, however, proved more significant as the game progressed.

Wynn was not at his best. Six times, he walked either the first or the second man in an inning (the second, third, fifth, sixth, and seventh). In the fifth, he issued back-to-back free passes after the first out. Through guile, however, along with a dizzying assortment of sliders, curves, and the occasional knuckleball, Wynn kept the Red Sox off-balance, fending off further trouble.

Wynn’s mound opponent, veteran righty Tom Brewer, was pitching a very strong game. At age 27, the South Carolinian was, like Wynn, looking for a bounce-back year. An All-Star in 1956 when he won 19 games, Brewer was coming off a lackluster 12-12 campaign. Both pitchers exchanged zeros, but the Red Sox threatened in the top of the eighth. Don Buddin worked a leadoff walk, advancing to second on a wild pitch. After a fly to deep right, Buddin scampered to third. Wynn settled down, however, striking out the next two batters.

In the bottom of the eighth, Wynn was scheduled to bat leadoff. One of the better-hitting pitchers throughout his career, he had already collected a double in the game. He took two quick balls, then a strike, before lifting a high drive to left field. It was deep, but playable, for Bill Renna. At the base of the wall, Renna timed his leap, reached … and the ball bounced off his glove into the waiting hands of one Bobby Sura, a 16-year-old from the nearby town of Argo.1 Wynn’s home run, his first of the season and the 15th of his career, put Chicago up, 1-0.

Wynn set the Red Sox down in order in the ninth, including a game-ending strikeout of Renna. That gave Wynn 14 K’s in the game (a career high), increasing his lifetime total to 1,849, the most among all active pitchers. After the first-inning hit by Runnels, Wynn did not allow another (although he walked seven). It was the second and final one-hitter of his career, the closest he ever came to a no-hitter. Later, in the clubhouse, Wynn admitted that he should never have directed Aparicio to reposition himself. “If I hadn’t, he would have fielded it easily,” he said. “After the game, Looey told me he’d never listen to me again.”2

Brewer, the Boston pitcher, was equally parsimonious, surrendering only five hits and one walk in going the distance. He wound up with a 10-12 record in 1959, coupled with a 3.76 ERA. Shoulder problems ultimately forced him from the game at 29.

The victory was the 252nd of Wynn’s career. Only Warren Spahn had tossed more shutouts among active moundsmen (45 to 38). Wynn would finish out his Hall of Fame career in 1963 with an even 300 victories.

The 13,000-plus in attendance savored the early-season highlight, a rousing start to the Veeck Era. The game helped kick-start a fantastic season for Wynn, who led the majors in wins (22), and the AL in starts (37) and innings pitched (255⅔). He also topped all of baseball in walks (119) for the second time. Wynn won the Cy Young Award in a landslide, back at a time when it was given to the single best pitcher in the major leagues.3 The White Sox, meanwhile, soon earned the nickname 4“The Hitless Wonders,” riding their strong pitching and fielding all the way to the 1959 World Series, only to fall to the Los Angeles Dodgers in six games.

Sources

In addition to the sources mentioned in the notes, the author consulted baseball-reference.com and retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Richard Dozer, “Wynn Wins 1-Hitter, 1-0, on Own Homer,” Chicago Tribune, May 2, 1959.

2 Munzel, “Hats Off…!” Sporting News, May 13, 1959.

3 So who got the better of the trade? Wynn went 28-29 for Chicago over the next three seasons before being released, his career win total stuck at 299. He returned to Cleveland to pick up his 300th victory. Al Smith batted .276 in his five seasons in Chicago, including an All-Star Game appearance in 1960. He is most famous for the photograph taken of him in the 1959 World Series: Standing with his back to the Comiskey Park wall on a Charlie Neal home run, Smith is doused on the head when an excited fan accidentally spills a cup of beer on him. Fred Hatfield collected only one hit in his Indians career, and while Minnie Minoso had two fine seasons in Cleveland, his stay was short-lived, as the Tribe dealt him back to the White Sox after the 1959 campaign.

4 The sobriquet was first applied to the 1906 White Sox, who won the AL pennant despite a team batting average of only .230, then captured the World Series from the crosstown Cubs, whose .763 season winning percentage still stands as the best in the majors.

Additional Stats

Chicago White Sox 1

Boston Red Sox 0

Comiskey Park

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.