May 11, 1946: Braves Field hosts its first game under the lights

In their ongoing struggle to outdraw the Red Sox, their team’s longtime rivals for the affections of New England baseball fans, owners of the Boston Braves usually finished on the losing end. Cavernous Braves Field, situated just off an unexciting stretch of automobile dealerships on Boston’s Commonwealth Avenue, was no match for cozy Fenway Park and the more inviting hotels and restaurants of Kenmore Square. Whether longtime residents or businessmen in town for a quick junket, fans usually chose the Red Sox and Fenway — especially if Ted Williams was expected in the Red Sox lineup.

In their ongoing struggle to outdraw the Red Sox, their team’s longtime rivals for the affections of New England baseball fans, owners of the Boston Braves usually finished on the losing end. Cavernous Braves Field, situated just off an unexciting stretch of automobile dealerships on Boston’s Commonwealth Avenue, was no match for cozy Fenway Park and the more inviting hotels and restaurants of Kenmore Square. Whether longtime residents or businessmen in town for a quick junket, fans usually chose the Red Sox and Fenway — especially if Ted Williams was expected in the Red Sox lineup.

After World War II, however, new Braves majority owner Louis Perini seemed poised to finally make some major inroads in this uphill climb to city supremacy. A self-made success as a contractor, Perini began putting together a team that he hoped would be as impressive as any of his company’s bridges or buildings. He used a breathtaking three-year, $100,000-plus salary to lure to town baseball’s best manager — Billy Southworth of the St. Louis Cardinals — and as Southworth assembled an All-Star lineup, Perini turned his sights to sprucing up Braves Field. He put in new concessions stands and a new outfield fence before the 1946 season, but his biggest change could be seen by fans as they passed by the ballpark starting that February — eight new light towers rising into the sky.1

The Braves were 12th of the 16 major-league teams to begin playing night home games, but the first in Boston.2 Fenway was still a day-game-only venue, and Perini planned on big crowds for each nocturnal contest. The $152,000 lighting system included four towers in the grandstand, three beyond the outfield fence, and one by the separate-admission bleacher section known as the Jury Box. Early accounts of its illumination potential described it as the equivalent of up to four times the average American living room, with the outfield lighting only slightly less.3

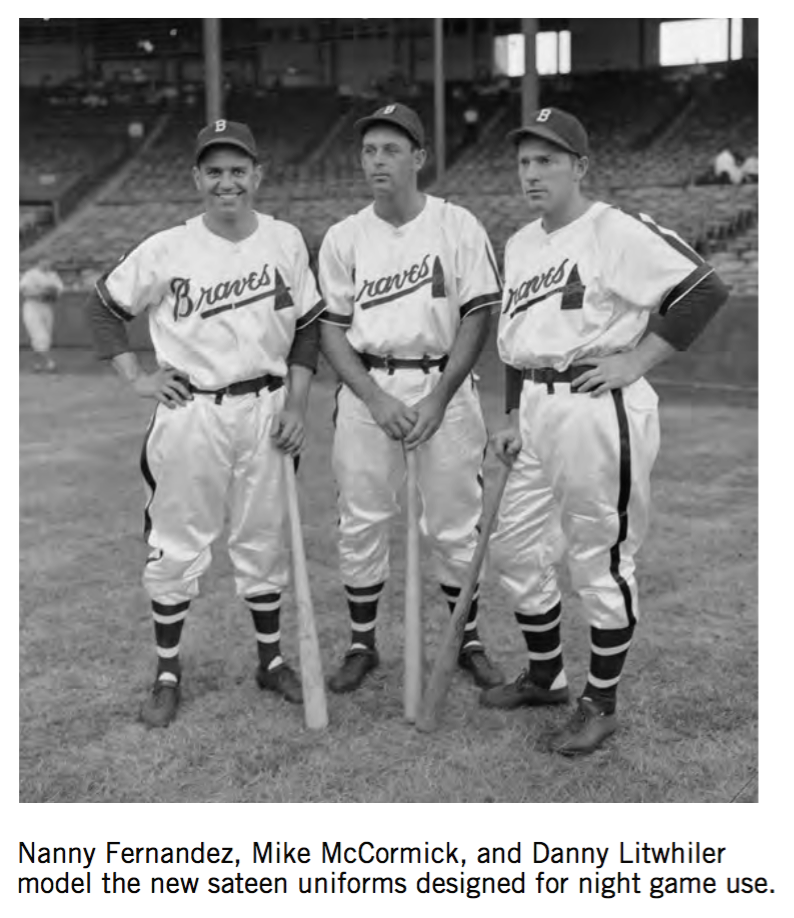

Of the 77 home games on the 1946 Braves schedule, nearly one third (24) were scheduled as night contests. The first was slated for Saturday, May 11, against the New York Giants, and there was tremendous buildup to the event. A special ticket booth was set up at Braves Field and opened for extended hours starting in early May specifically for the sale of night and Sunday doubleheader tickets, and new satin uniforms — then referred to as “sateen” — were designed for Braves players to wear in night games. The uniforms, the Boston Globe reported, would have “dazzling luster” to make “a lot of hairy-chested athletes look like so many sparkling diamonds.” The goal was to give fans in the stands a clearer view of the home club, and neon foul poles and gold-painted box seats were added for the same purpose.4

The opening night’s agenda for May 11 was published in the Globe like a theatrical playbill. Prior to the Giants-Braves game at 8:30 P.M., there would be a concert from 7:00 to 7:30 by a 75-piece band; a shorter concert from 7:30 to 7:45 by the “Braves Field Troubadours,” a trio of musicians who routinely played in the stands at home games; an appearance by baseball comedian Al Schacht from 7:45 to 8:00; fireworks from 8:00 to 8:25; and, finally, a spotlight introduction of the players. Schacht was told to stay in New York when a rainstorm earlier in the day dampened the field and made his act potentially treacherous to the diamond, but the rain had stopped by evening and the rest of the festivities went off well.

Among the 37,407 in attendance were 30 busloads of fans brought in from outside Boston to be on hand at the Saturday night soiree, and most were in their seats when Baseball Commissioner Happy Chandler’s wife, Mildred, flicked the switch that brightened the 768-bulb, 112,220-volt system,5 and National League President Ford Frick threw out the first ball.6 Right-hander Johnny Sain took the mound for the Braves, third baseman Bill Rigney settled into the batter’s box, and night baseball in Boston was officially under way.

Things were eventful but sloppy early on. Rigney walked and stole second, but Sain got through the first inning unscathed while recording the ballpark’s initial night strikeout victim in Jess Pike. The Braves got two aboard in the bottom of the first off New York left-hander Monty Kennedy, who like Sain seemed to struggle initially with the darker setting by hitting Johnny Hopp and walking Tommy Holmes. But the promising frame ended when Ray Sanders struck out and Hopp was thrown out stealing to complete a double play, with the throw to second coming from Giants catcher Ernie Lombardi — a former batting champ with the ’42 Braves and one of two future Hall of Famers (along with New York first baseman Johnny Mize) to play in the contest.

Things were eventful but sloppy early on. Rigney walked and stole second, but Sain got through the first inning unscathed while recording the ballpark’s initial night strikeout victim in Jess Pike. The Braves got two aboard in the bottom of the first off New York left-hander Monty Kennedy, who like Sain seemed to struggle initially with the darker setting by hitting Johnny Hopp and walking Tommy Holmes. But the promising frame ended when Ray Sanders struck out and Hopp was thrown out stealing to complete a double play, with the throw to second coming from Giants catcher Ernie Lombardi — a former batting champ with the ’42 Braves and one of two future Hall of Famers (along with New York first baseman Johnny Mize) to play in the contest.

Despite more baserunners in the second inning — a walk for New York off Sain, two walks and a single for Boston off Kennedy — neither team scored (another double play, this time a 6-4-3 grounder by Stew Hofferth with Nanny Fernandez on first, hurt Boston). Both clubs, however, broke through in the third. The Giants went up 1-0 on a single by Lombardi to drive in Rigney, and the Braves tied it on an unearned tally when Ryan walked, went to second on a sacrifice bunt by Hopp, and scored when he stole third and Lombardi’s throw to nab him got past third baseman Rigney.

Still in the third, the Braves blew a chance to move ahead when they suffered their third double play in as many innings on a 4-6-3 grounder off the bat of Sanders with Holmes at first. So many early squanders are usually a bad omen, and things only got more frustrating for the home fans when the Braves left two men on in the fourth inning without scoring after Sain had retired the Giants in order in the top of the frame (including the fifth of his seven strikeouts over seven innings).

New York’s biggest inning against Sain came in the fifth, when they scored twice on four singles, including run-scoring hits to center by Mize and rookie center fielder Jack Graham. Sain settled down after this, but the Braves had exhausted their best chances against Kennedy early and were quiet the rest of the night. Boston still trailed in the eighth, 3-1, when young right-hander Steve Roser came on for the Braves in relief, and in the ninth the Giants padded their lead to 5-1 on a Johnny Rucker double, an RBI triple by Pike (who had struck out three times against Sain), and a run-scoring single by Mize. Kennedy (2-0 in the young season) went the distance, allowing eight walks but just one unearned run, while Sain fell to 3-3.

Despite the final score, which dropped Southworth’s revamped club under .500 at 9-10, reviews of Boston’s first major-league night game were positive. It was reported that outfielders had no problems with fly balls, and even with the rain earlier in the day the stands were nearly full. This would be the case for the rest of the summer, as the novelty of night ball and a competitive team that finished a solid fourth in the National League helped the Braves set a franchise attendance record of 969,673 (more than double their prior seasonal mark). But the Red Sox picked the same year to go 104-50 and romp to the American League pennant. Even without night ball, Ted Williams and Co. drew 1,416,944 to Fenway Park.

Perini was not deterred. Convinced that night games were the future of the sport, he proposed at the December 1946 winter meeting in Los Angeles that teams be given the right to schedule as many such contests as they wanted — a suggestion that was met with an uproar from many other owners. The three New York teams, for instance, had an agreement between them to have no more than 14 night games apiece per season.7 Perini was thinking more along the lines of 30 or 40, and by 1948 he had his wish.

Braves attendance peaked that year at 1,455,439, when the team captured its last NL pennant in Boston. The Red Sox, who added lights in 1947, were just a shade better at 1,558,798, but the Braves would never quite catch them. The crowds at Braves Field plummeted along with the team’s fortunes over the next several seasons, and by 1952 Perini wondered if too many televised night games — TV was then the new rage, threatening the movie industry — were hurting the turnout as much as a seventh-place team.

“Should television programs become so attractive every evening of the week that they are keeping people at home,” Perini told reporters at the December 1952 winter meetings in Phoenix, “baseball will have to go back to playing all its games in the daytime.” He said he planned just 28 night games for the ’53 season.8

Perini never would see how the change might impact his Boston crowds, however. By 1953, the Braves were playing all their home games — day and night — in Milwaukee.

This article appeared in “Braves Field: Memorable Moments at Boston’s Lost Diamond” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and Bob Brady. To read more articles from this book, click here.

Sources

In addition to the sources mentioned in the Notes, box scores for this game can be seen on baseball-reference.com, and retrosheet.org at:

http://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/BSN/BSN194605110.shtml

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1946/B05110BSN1946.htm

“Lo, the Rich Indian’s Wigwam is Ablaze With Light and Color,” Boston Sunday Globe, May 11, 1946.

“37,407 See Braves Arclight Debut; Bonham Ends Red Sox Streak, 2-0,” Boston Sunday Globe, May 12, 1946.

“TV May Force All Day Baseball Games — Perini,” Boston Globe, December 2, 1952.

“37,000 Attend Night Game,” Boston Sunday Herald, May 12, 1948.

“Giants Win, 5-1, before 37,407,” Boston Sunday Post, May 12, 1948.

The Illumination of Braves Field in Boston, postcard produced by Boston Braves Historical Association, quoting from 1946 Vol. 1, issue 1 of Braves Bulletin, 2014.

“Braves Ask Unlimited Night Baseball as Majors Convene,” New York Times, December 6, 1946.

Caruso, Gary. The Braves Encyclopedia (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1995).

Kaese, Harold. The Boston Braves (New York: Putnam Press, 1948).

Klapisch, Bob, and Pete Van Wieren, The World Champion Braves: 125 Years of America’s Team (Turner Publishing, Atlanta, 1995).

Notes

1 At the time Braves Field was being lighted, the Braves were run by the Three Little Steam Shovels ownership triumvirate, Perini, Rugo and Maney. (Perini didn’t buy out his fellow majority owners until 1951-52.) However, Perini clearly was the “face” of ownership, assuming the top executive position, and was the principal decision-maker.

2 Given wartime restrictions, the Braves had to apply to the War Production Board to obtain approval for this construction. World War II had ended in Europe and was winding down in the Pacific. Approval was granted on July 14, 1945. Construction commenced on December 5, 1945, and by March 26, 1946, all towers were in place. A preliminary test of the lighting system occurred on April 24 and the final test was deemed a success on May 1. See William Sullivan, ed., Braves Bulletin: A Newspaper dedicated to Sports Fans who follow the Braves, May 11, 1946 issue (Volume 1, Number 1), and the Summer 2014 issue of the Boston Braves Historical Association Newsletter, 5.

3 Sullivan.

4 “Al Schacht, Bane, Fireworks — All at B’s Night Game,” Boston Globe, May 9, 1946.

5 Jerry Nason, “Lo, the Rich Indian’s Wigwam Is Ablaze With Light and Color,” Boston Globe, May 11, 1946. The Hartford Courant and Retrosheet both give attendance at 35,945. Regardless, the Courant reported that this was Braves’ highest game attendance in 13 seasons, since 1933, when the Braves contended for the pennant late in the season. Hartford Courant, May 12, 1946; New York Times, May 12, 1946.

6 “Giants Trip Braves With Kennedy, 5-1,” New York Times, May 12, 1946.

7 John Drebinger, “Braves Ask Unlimited Night Baseball as Majors Convene,” New York Times, December 6, 1946.

8 Hy Hurwitz, “TV May Force All Day Baseball Games — Perini,” Boston Globe, December 2, 1952.

Additional Stats

New York Giants 5

Boston Braves 1

Braves Field

Boston, MA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.