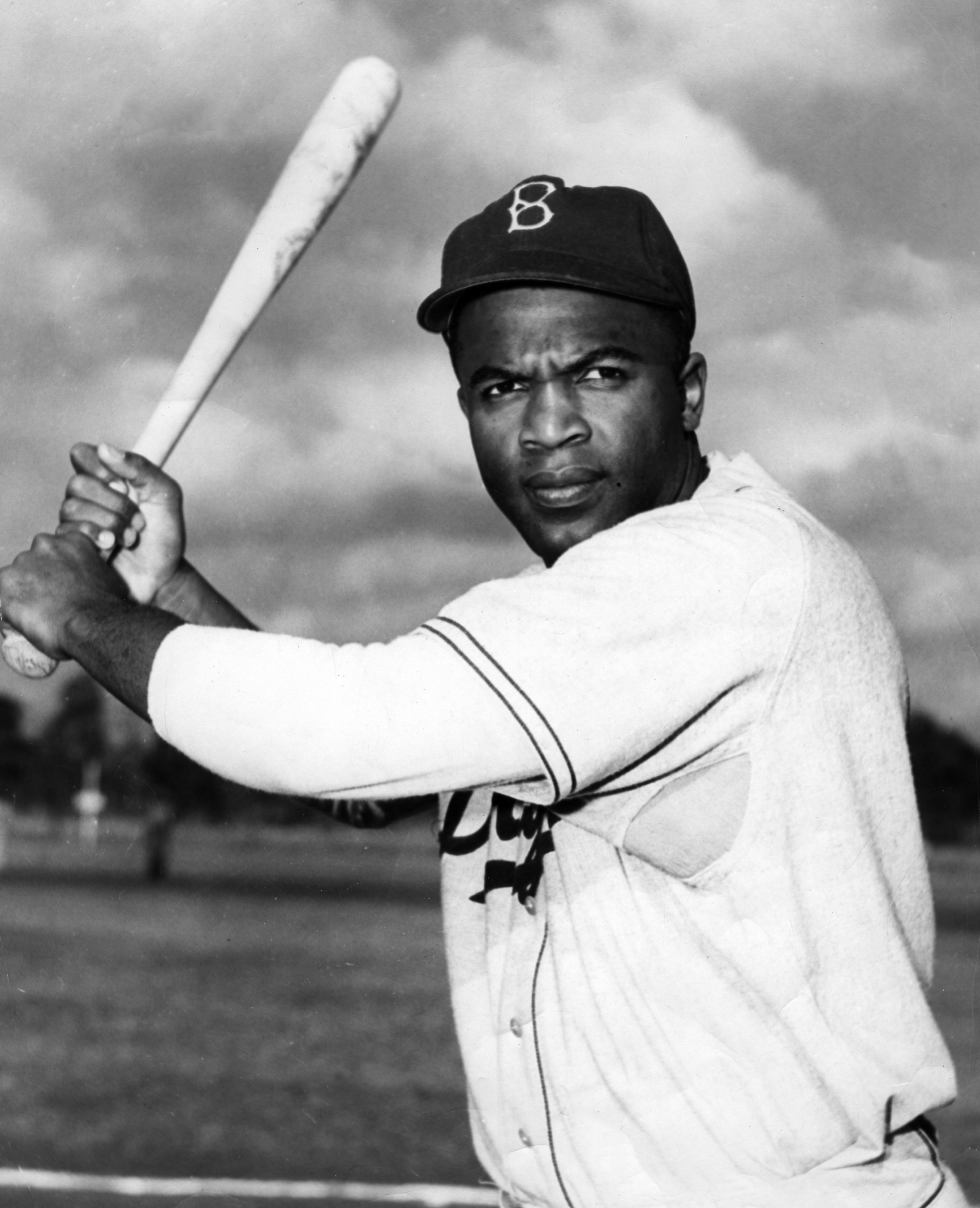

May 13, 1947: Jackie Robinson makes first appearance in Cincinnati with Dodgers

Before Jackie Robinson had been in the National League a month, some observers were ready to write him off and declare baseball’s “great experiment”1 a failure.

Before Jackie Robinson had been in the National League a month, some observers were ready to write him off and declare baseball’s “great experiment”1 a failure.

“There is no assurance that Jackie Robinson will continue as [the Brooklyn Dodgers’] first baseman,” sportswriter Lou Smith informed readers of the Cincinnati Enquirer hours before Robinson’s first appearance at Crosley Field on May 13. “Robinson, who is hitting around the .225 mark, is no Dolph Camilli in the field. But for the fact that he is the first acknowledged Negro in major league history and so much attention has been focused on him he would have been benched a week or two ago.”2

Since his official debut on April 15, 1947, Robinson had been hit by pitches three times and regularly experienced fastballs “right under his nostrils.”3 He had suffered vile racial taunts,4 heard rumblings that an opposing team would refuse to take the field against him,5 and received threats serious enough to launch a police investigation.6 As if that weren’t enough to trouble the rookie’s mind, he was attempting to master a new position and had recently endured an 0-for-20 slump.

Nonetheless, Lou Smith could hardly have been more wrong. For one thing, his statistics were out of date. Robinson had been batting .225 on May 1, but by the time he reached Cincinnati two weeks later, he was riding a nine-game hitting streak that had lifted his average to .263. As for his fielding, Robinson had previously played shortstop for the Kansas City Monarchs and then second base for the Montreal Royals in 1946, his first year in the Brooklyn organization. He had gotten a crash course at first base only weeks before the 1947 season started, as the Dodgers sought a way to fit him into their lineup.

In any case, people wanted to see “the colored boy.”7 A total of 27,164, including Commissioner A.B. “Happy” Chandler, turned out for Robinson’s Cincinnati debut. The date marked the Reds’ first night game of the season, and pregame attractions included a band, festivities involving a local Masonic organization, and a fireworks display.

But reporters were alert to a large number of people in the ballpark “who wouldn’t … have gone near the place” except for Robinson’s presence.8 Cincinnati, just across the Ohio River from the former slave state of Kentucky, was one of the major leagues’ southernmost cities. It was “still a segregated town,” in the words of Reds team historian Greg Rhodes,9 and would largely remain so through the 1950s.10 According to Hank Thompson — a former Negro Leaguer who cracked the big time three months after Robinson — Cincinnati had “the worst fans” in the major leagues.11 Despite dramatic growth in the city’s Black population throughout the 1940s,12 the Reds — who would be the next-to-last National League team to integrate, holding out until 1954 — did not enjoy a large patronage among the city’s Black residents. The Phillies, who did not integrate until 1957, were the last National League team to do so.

Yet on the night of Robinson’s Cincinnati debut, one observer estimated that there were 5,000 Black spectators.13 Another guessed 10,000.14 The next day, when the two teams played in daylight before a much smaller crowd of 6,688, Lou Smith reported that “at least half” of those in attendance “were members of Jackie’s race.”15 To Reds rookie Eddie Erautt, remembering the scene years later, it seemed that the park on that first night was “packed — all Blacks.”16

One reporter noted that most of the Black spectators occupied the cheaper seats, in the bleachers or the back rows of the grandstand.17 Some of those fans had traveled more than 400 miles, delivered on a train that left Birmingham, Alabama, in the morning and picked up additional passengers as it rolled northward.18

Unlike in some National League cities, Robinson could stay at the same hotel as his teammates in Cincinnati, the Netherlands Plaza. The newspapers applauded that progressive stand but didn’t mention that he was not allowed to use the hotel swimming pool and took his meals in his room.19 While Robinson was in town, the Cincinnati Post published an interview in which he was described as “unassuming and courteous … [and] cognizant of the responsibility he shoulders for his race.” The story noted that Robinson had attended UCLA and was married to his “college sweetheart.”

The story also emphasized that the ballplayer had “remained aloof from any unjust criticism that has been directed at him.”

“It’s tough at times,” Robinson said, “because I like to talk.”20

Nothing extraordinary happened on the field. In his first four plate appearances, against Reds starter Johnny Vander Meer, Robinson grounded out, walked, lined out to left on “one of the hardest-hit balls of the game,”21 and was narrowly thrown out on a bunt. In the ninth inning he drove in a run with “a clean single through the pitcher’s box”22 off reliever Joe Beggs, and subsequently scored on a single by Carl Furillo. In the field he made “no great play”23 and recorded just three putouts, having so little to do, in the view of one writer, that “he appeared disinterested at times.”24

Brooklyn led 1-0 early but Cincinnati pulled ahead in the third inning, chasing Dodgers starter Harry Taylor with a rally that featured two bases-loaded walks and a two-run single by Bert Haas. After two Brooklyn errors aided Cincinnati’s three-run seventh, the Reds led 7-2 before the Dodgers narrowed the gap in the ninth.

The Dodgers outhit the Reds 13-5 but they also made three errors and used six pitchers (who issued eight walks) as the home team won “a weird struggle,” 7-5.25 The next day, Robinson singled twice off Ewell Blackwell, extending his hitting streak to 11 games and boosting his average to .274. The Dodgers lost again, 2-0.

For all the ink that was expended on Robinson’s first visit to Cincinnati, there are still things we don’t know. Like the widely divergent estimates of the number of Black spectators, there is the matter of those spectators’ response. Most reporters on the scene agreed with Si Burick, who had used his Dayton Daily News column to reprint an editorial from the Black-owned Pittsburgh Courier urging Robinson’s supporters to conduct themselves with decorum and restraint. In Cincinnati, Burick wrote, Robinson was cheered every time he came to bat but he received “no bigger hand than any other ballplayer,” and his fans were “orderly and well-behaved.”26 By contrast, later recollections by both players and spectators suggest that fans reacted loudly to every move Robinson made.27

And then there’s the oft-repeated story of how Dodgers shortstop Pee Wee Reese stilled a hostile crowd by walking over to first base and putting his hand on Robinson’s shoulder. The moment, commemorated by a statue outside Brooklyn’s MCU Park, is often placed at Crosley Field in May 1947, as in the inscription at the base of the statue. But the story has been widely questioned. It was never told until years later, even by supposed eyewitnesses. Robinson, in his autobiography, placed the incident in Boston.28 His wife, Rachel Robinson, questioned by author Jonathan Eig in 2005, said the incident never happened — at least not in 1947.29

Certainly there is no contemporary mention of any such episode in Cincinnati in May 1947. Cincinnati Post sports editor Joe Aston devoted an entire column to Robinson’s activities and surely would have mentioned such an event if it had occurred. According to Aston, the only witness who raised the issue, there was no racist invective directed at Robinson at all.

“If anyone had any objection to Jackie’s presence on the field,” Aston wrote, “he failed to make himself heard.”30

Admittedly that seems unlikely. Perhaps the most bigoted spectators were cowed by the unaccustomed number of Black faces in the park.

One thing is certain. By the time the Dodgers left Cincinnati, they were settled on Robinson as their first baseman. Two men, Ed Stevens and Howie Schultz, had shared the position in 1946. On May 10 the Dodgers had sold Schultz to the Philadelphia Phillies. While in Cincinnati, they optioned Stevens to Montreal.

By that time, too, most of the Ohio writers were convinced, or at least well on their way.

“Apparently he has what it takes,” conceded Frank Y. Grayson in the Cincinnati Times-Star.31

For his part Robinson, always polite and tactful during his first season with the Dodgers, said in his weekly newspaper column (ghostwritten by Pittsburgh Courier sports editor Wendell Smith) that he “had a nice experience in Cincinnati.”32

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author used the Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org websites for statistics and team information.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/CIN/CIN194705130.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1947/B05130CIN1947.htm

Notes

1 The phrase, borrowed from Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, was applied to the breaking of baseball’s color barrier in Jules Tygiel’s book Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press), 1983.

2 Lou Smith, “What’s Matter, Redleg Fans Ask,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 13, 1947: 18. Camilli was a slick-fielding first baseman who had played the position for Brooklyn from 1938 to 1943.

3 Smith, “Reds Move to Philly; Night Game Carded; Young Is Hitting Hard,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 15, 1947: 2-C.

4 Joe Reichler, “Frick, Breadon and Dyer Have Views on Dodger Player,” Kingston (New York) Daily Freeman, May 9, 1947: 10; see also Edgar G. Brands, “Game’s Officials Silent on Robinson Incident,” The Sporting News, May 21, 1947: 4.

5 Stanley Woodward, “General Strike Conceived,” New York Herald Tribune, May 9, 1947, reprinted in The Sporting News, May 21, 1947: 4.

6 Hy Turkin, “Police Investigate Poison Pen Threats to Jackie Robinson,” New York Daily News, May 10, 1947: 25.

7 Bob Husted, “The Referee,” Dayton Herald, May 14, 1947: 30.

8 Joe Aston, “Big Night at the Ballpark,” Cincinnati Post, May 14, 1947: 20.

9 Greg Rhodes and John Erardi, Cincinnati’s Crosley Field: The Illustrated History of a Classic Ballpark (Cincinnati: Road West Publishing, 1995), 120.

10 Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy, 304.

11 Tygiel.

12 Jonathan Eig, Opening Day: The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Year (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007), 124.

13 Aston.

14 Harold C. Burr, “Chandler Opens Door for Lippy Next Year,” Brooklyn Eagle, May 14, 1947: 19.

15 Smith, “Erautt to Face Phils; Rickey Praises Blackie,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 15, 1947: 2-C.

16 Eig, 127.

17 Aston.

18 Rhodes and John Snyder, Redleg Journal: Year by Year and Day by Day with the Cincinnati Reds (Cincinnati: Road West Publishing, 2000), 328.

19 Si Burick, “Si-ings,” Dayton Daily News, May 14, 1947: 20. See also “Varied Policies at Hotels Greet Robinson on Trip,” The Sporting News, May 21, 1947: 8.

20 “Robinson Is Determined to Make Grade in Majors,” Cincinnati Post, May 14, 1947: 21.

21 Smith, “Blackwell to Face Hatten Today; Tatum Goes Well in Debut Here,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 14, 1947: 16.

22 Aston.

23 Burick.

24 Tom Swope, “Dodgers Hand Game to Reds,” Cincinnati Post, May 14, 1947: 21.

25 Frank Y. Grayson, “In Weird Struggle Under the Lights, Redlegs Conquer Durocherless Bums,” Cincinnati Times-Star, May 14, 1947: 23.

26 Burick.

27 Eig, 126-27.

28 Jackie Robinson, as told to Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1972), 77.

29 Eig, “Telling It the Right Way,” in Michael G. Long, ed., 42 Today: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (New York: New York University Press, 2021), 37.

30 Aston.

31 Grayson, “Grayson’s Notes of Yesterday’s Game,” Cincinnati Times-Star, May 15, 1947: 26.

32 Robinson, “Greenberg and Gustine Encouraged Me a Lot,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 24, 1947: 14.

Additional Stats

Cincinnati Reds 7

Brooklyn Dodgers 5

Crosley Field

Cincinnati, OH

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.