May 23, 1948: Boston Braves win two for Jimmy Fund

Two early-season games at Braves Field on May 23, 1948, were quickly forgotten amid far more exciting contests from that championship season, but the events that unfolded around the Sunday doubleheader were significant for reasons that go far beyond baseball.1

Two early-season games at Braves Field on May 23, 1948, were quickly forgotten amid far more exciting contests from that championship season, but the events that unfolded around the Sunday doubleheader were significant for reasons that go far beyond baseball.1

The story starts a few miles from the ballpark. In the basement of what is now Boston Children’s Hospital, Sidney Farber, M.D., was working in a one-room laboratory probing the mysteries of leukemia — a cancer that was then 100 percent fatal for children and adults. In November 1947 he found a drug that achieved temporary remissions in 10 of 16 pediatric patients, and his findings were reported in the New England Journal of Medicine in the spring of 1948.2

Members of the Variety Club of New England, a social and charitable organization connected with the theater and entertainment industry, were looking for worthy causes to support financially. When they heard about Dr. Farber’s findings they decided to back his cause, and their fundraising efforts resulted in $45,536 and formation of the Children’s Cancer Research Foundation, or CCRF (now known as Dana-Farber Cancer Institute). Next, hoping to bankroll a state-of-the-art research and treatment facility for Dr. Farber, Variety Club executive director William S. “Bill” Koster and fellow Boston-based member George Schwartz came up with a unique and winning idea.3

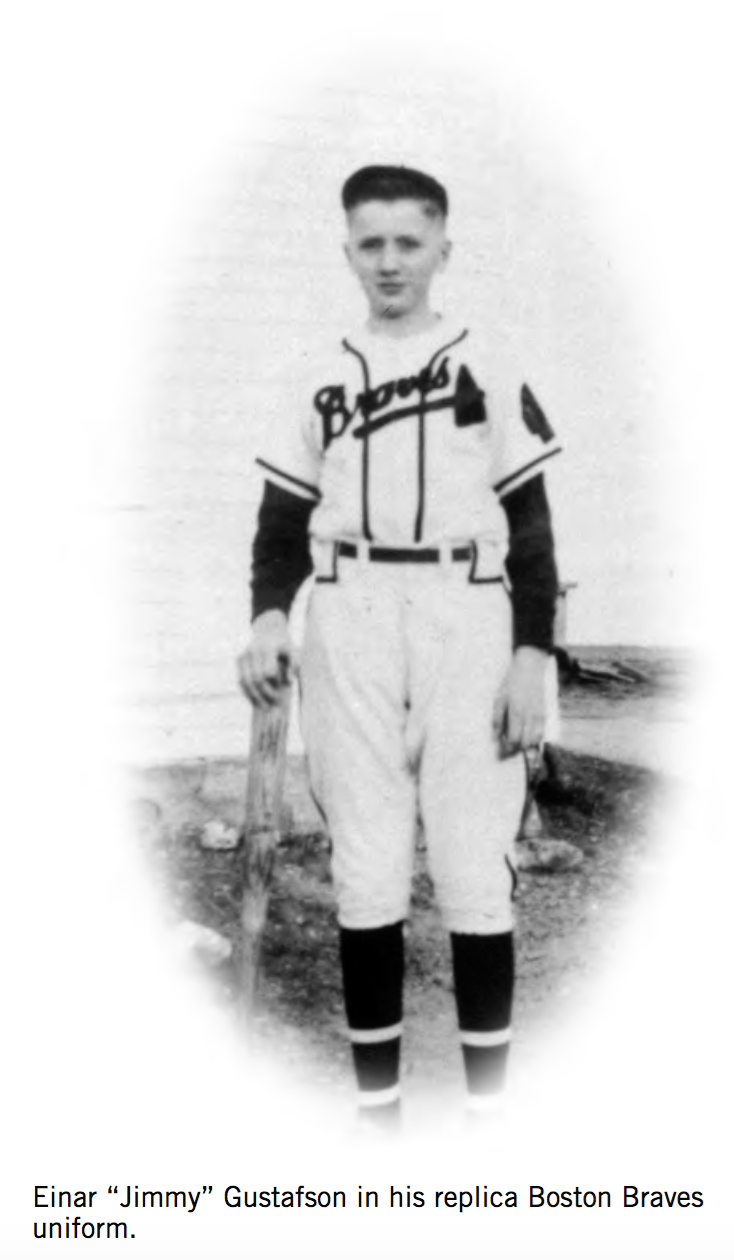

Using Schwartz’s Hollywood connections, they arranged for a live nationwide broadcast of the popular Saturday night radio game show Truth or Consequences to be aired in part from the hospital bedside of one of Dr. Farber’s patients. As the show’s host, Ralph Edwards, asked questions in front of his California audience, they were heard and answered in Boston Children’s Hospital by Einar Gustafson, a 12-year-old boy whom Dr. Farber had dubbed “Jimmy” to protect his privacy. Gustafson, a tall, blond farmer’s son from tiny New Sweden, Maine, was being treated for Burkitt’s non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, a form of cancer then fatal in about 85 percent of pediatric patients.

This is where the baseball comes in. Hearing that Gustafson’s favorite team was the Boston Braves, Schwartz and Koster worked with Braves publicity director Billy Sullivan to arrange for members of the club to surprise Gustafson with a visit to his room during the live broadcast. After a 6-4 loss to the Cardinals that afternoon at Braves Field, players changed into their street clothes and made the trip to the hospital. There they were met by Sullivan and representatives from the Variety Club, who led them to Gustafson’s room, where microphones had been hooked up beforehand.

The crowd in Hollywood and listeners around the country heard Gustafson — known only as “Jimmy” — grow increasingly excited as players arrived one-by-one at his bedside with autographed balls, bats, and jerseys. Manager Billy Southworth came last with an authentic woolen team uniform tailored to Gustafson’s size, after which a piano was rolled in so the group could sing “Take Me Out to the Ballgame.” Gustafson, gloriously off-key, was heard above all the others. Southworth invited Gustafson out to the next day’s doubleheader at Braves Field against the Cubs, and after the radio feed from Boston went out, Edwards made an appeal to listeners: If $20,000 could be raised for the CCRF, “Jimmy” would receive a television set on which to watch Braves games.

Before the broadcast had even ended, listeners who heard it on their car radios were driving up to the front of Boston Children’s Hospital and handing coins and dollar bills over at the front desk. In the days to come thousands of envelopes marked “Jimmy – Boston, Mass.” arrived at the hospital stuffed with change, and Braves players attended picnics, car washes, and other fundraising events that brought in more cash. Gustafson soon got his TV, and by summer’s end, $231,485.51 was raised for the “Jimmy Fund.” 4

It was all heady stuff for young Einar “Jimmy” Gustafson, but what he remembered most was the Sunday doubleheader he attended as the guest of his heroes. The Braves entered the twin bill with a mediocre 14-13 record, and the sixth-place Cubs were just the tonic they needed. Although Chicago took a 5-1 lead in the third inning of the opener, the Braves got close in their half of the third on a three-run double by Jeff Health, and then moved ahead 8-5 with four more in the fourth — including two on a Phil Masi double. Catching both games of the doubleheader, Masi would go 6-for-9 with six RBIs to break a 6-for-54 slump.

Boston’s bats were quiet for the rest of the first game, but the 8-5 lead stood up thanks to brilliant relief pitching by Clyde Shoun. Bailing out struggling starter Bill Voiselle, Shoun threw six innings of no-hit ball and retired 18 of the 19 men he faced. Making the feat even more impressive was that it was his first appearance in three weeks. “I was pleased and tickled pink,” manager Southworth said of the effort, noting that Shoun “has kept himself ready by warming up every day in the bullpen.” Although he had often started in the majors previously, Shoun said he was fine with being used almost exclusively in relief due to Boston’s strong rotation.5

A case in point came that same afternoon, when rookie Vern Bickford hurled a complete game in Boston’s 12-4, sweep-completing victory. No comeback was needed in this one, as the Braves exploded for six hits, five walks, and eight runs in the third inning to move ahead, 9-1. Two-run singles by Masi and Frank McCormick were crucial in the early uprising, and both, as well as leadoff man Tommy Holmes, had three hits. All told, the Braves had 26 hits in the two games, but interestingly not a single home run. They didn’t need any, thanks in large part to 20 walks (10 in each contest) given up by Chicago pitching.

The sweep moved Boston into a third-place tie with the Pittsburgh Pirates, and delighted the crowd of 31,693 on hand at Braves Field. Among those watching from a box seat, alongside his doctor and nurse, was Gustafson. Although he was not introduced to the crowd and Boston players didn’t visit with him in order to continue preserving his privacy, “Jimmy’s” new buddies smiled at him throughout the day. Gustafson left after the big third inning of the second contest because, as Arthur Siegel of the Boston Traveler noted, “he was beginning to droop a bit, and the doctor thought this had been quite a large day for the boy. There was fear it would become too much for him. So Jimmy went back to the hospital and for him, because he does not know how seriously ill he really is, there loomed nothing but bright days ahead.”6

Siegel was not being overly dramatic. Due to the grim statistics then associated with all children’s cancers, Gustafson was not expected to survive. But as the Braves did in recovering from their early-season mediocrity to move into first place in mid-June and eventually win the pennant, the boy rallied. Gustafson was home on his family farm by that fall, and the tremendous fundraising surrounding his radio appearance was the springboard for the construction of a four-story cancer research and treatment center for Dr. Sidney Farber and the CCRF. Located less than a block from Boston Children’s Hospital, it was named — appropriately — the Jimmy Fund Building.7

Here Dr. Sidney Farber and his colleagues would continue their noble work. When the Jimmy Fund Building opened in January1952, Braves representatives at a celebration luncheon included owner Lou Perini, PR man Billy Sullivan, and player-manager Holmes. And even after the Braves moved to Milwaukee the next year, the connection between Boston baseball and Dr. Farber continued — as Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey accepted Perini’s appeal to make the Jimmy Fund his team’s official charity.8

What became of Einar “Jimmy” Gustafson? Continuing to live out of the spotlight, and presumed dead by almost all but his hometown and Dr. Farber (with whom he corresponded), Gustafson grew up to be a father of three, a grandfather of six, and a long-distance truck driver. In 1998 he emerged from a half-century of silence to help the Jimmy Fund celebrate its 50th anniversary, and in an emotional reunion put together by the Boston Braves Historical Association, he was able to thank Holmes, Sullivan, and several of the others who brought him joy and a pennant during the toughest summer of his life.9

His was not the only happy ending. The most common childhood leukemia is 90 percent curable, and survival rates for many other pediatric and adult forms of the disease continue making extraordinary gains — thanks in large part to the night a group of weary ballplayers stopped in to make a sick little boy happy.

This article appeared in “Braves Field: Memorable Moments at Boston’s Lost Diamond” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and Bob Brady. To read more articles from this book, click here.

Sources

Baseball Reference.com.

“Braves Whip Cubs, 8-5, 12-4,” Boston Post, May 24, 1948.

“Baseball Therapy for Jimmy,” Boston Traveler, May 24, 1948.

“Shoun’s Wing, Masi’s Bat Helped Braves Take Bill,” Boston Traveler, May 26, 1948.

Dana-farber.org (history section).

Jimmyfund.org (Red Sox section).

Kaese, Harold. The Boston Braves (New York: Putnam Press, New York, 1948).

Wisnia, Saul. The Jimmy Fund of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2002).

Box scores for this game can be seen on baseball-reference.com, and retrosheet.org at:

http://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/BSN/BSN194805231.shtml

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1948/B05231BSN1948.htm

http://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/BSN/BSN194805232.shtml

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1948/B05232BSN1948.htm

Notes

1 It is also notable that this day was the one on which Norman Rockwell visited Braves Field to take photographs in preparation for his work “The Dugout.” See the separate essay at the end of this book.

2 Saul Wisnia, The Jimmy Fund of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2002). Dr. Farber’s findings were initially met with skepticism in the scientific community, since no drug had ever been proved effective against nonsolid tumors (those that are spread throughout the body and cannot be surgically removed). Those doctors intrigued enough to contact Dr. Farber received personal responses and an invitation to come to Boston with their patients.

3 Ibid. Over time, as more children had positive responses to his treatments, Dr. Farber found himself in urgent need of more space. He temporarily moved the CCRF into five rooms of an apartment building near Boston Children’s Hospital, but it was clear a full-size facility was necessary. The Variety Club, whose members had become wealthy and well-connected during the movie craze before and during World War II, made funding such a structure their top priority.

4 Ibid.

5 Tom Monahan, “Shoun’s Wing, Masi’s Bat Helped Braves Take Bill,” Boston Traveler, May 24, 1948.

6 Arthur Siegel, “Baseball Therapy for Jimmy,” Boston Traveler, May 24, 1948.

7 As a subtle tribute to the team that helped make the structure possible, two medallions emblazoned with the Braves logo – a regal Native American chief in full headdress – were placed by the entrance of the Jimmy Fund Building. They are still there. In November 2013 a longtime Jimmy Fund supporter, Jim Vinick, donated two statues to the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. They are placed on Binney Street in Boston and depict Dr. Sidney Farber looking up toward his then 12-year-old patient Einar Gustafson, “Jimmy,” who is shown wearing his Boston Braves uniform.

8 The Jimmy Fund continues to be a vital part of Red Sox fundraising efforts, and a gleaming new Yawkey Center for Cancer Care (named for Red Sox owners Tom and Jean Yawkey) now sits a few feet away from the original Jimmy Fund Building. A Jimmy Fund billboard was for many years the only advertising allowed by Tom Yawkey inside Fenway Park, and stood for decades atop the right-field grandstand and the Red Sox retired numbers. When modifications to the ballpark forced the billboard’s dismantling, a Jimmy Fund logo was placed on the Green Monster left-field wall – where it remains.

9 The Jimmy Fund of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Fifty years to the day after his radio appearance, Gustafson was re-introduced to Boston baseball fans on the field at Fenway Park on May 22, 1998. Truth or Consequences host Ralph Edwards was on hand for the ceremony, which included a recording of the original 1948 broadcast played over the loudspeakers. Gustafson spent the last years of his life making public appearances and helping with other fundraising efforts on behalf of Dana-Farber before dying on January 21, 2001, after suffering a stroke.

Additional Stats

Boston Braves 8

Chicago Cubs 5

Boston Braves 12

Chicago Cubs 4

Braves Field

Boston, MA

Box Score + PBP:

Game 1:

Game 2:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.