October 14, 1929: Bing Miller’s walk-off gives A’s the World Series title

It was another dramatic victory or staggering collapse, depending on perspective. After exploding for a World Series-record 10 runs in the seventh inning to win Game Four, the Philadelphia Athletics scored all of their runs in the ninth inning in Game Five to defeat the Chicago Cubs, 3-2, and capture their first championship since 1913 on Bing Miller’s thrilling game-ending double. “We outplayed and outlucked the Cubs,” gushed Connie Mack, A’s owner-manager. “No team in the world could have beaten us in this series.”1 The unsung hero of the game, however, was reliever Rube Walberg, whose spectacular performance was “one of the best examples of rescue pitching ever seen in a World’s Series,” submitted Philadelphia sportswriter James C. Isaminger.2

It was another dramatic victory or staggering collapse, depending on perspective. After exploding for a World Series-record 10 runs in the seventh inning to win Game Four, the Philadelphia Athletics scored all of their runs in the ninth inning in Game Five to defeat the Chicago Cubs, 3-2, and capture their first championship since 1913 on Bing Miller’s thrilling game-ending double. “We outplayed and outlucked the Cubs,” gushed Connie Mack, A’s owner-manager. “No team in the world could have beaten us in this series.”1 The unsung hero of the game, however, was reliever Rube Walberg, whose spectacular performance was “one of the best examples of rescue pitching ever seen in a World’s Series,” submitted Philadelphia sportswriter James C. Isaminger.2

The Tall Tactician had seemingly pulled all the right strings thus far in the fall classic against the Cubs (98-54), and this game was no different. Most pundits expected staff ace Lefty Grove, coming off his third straight season with at least 20 victories, to get the start with the title on the line. Surprisingly, he had made only two relief appearances thus far, tossing 4⅓ scoreless innings in Game Two and two in Game Four. However, Grove hadn’t been feeling “well enough to pitch at least nine innings,” revealed Mack after the A’s victory. “His pitching fingers have been sore.”3 Instead Mack stunned everyone by calling on Howard Ehmke again. The 35-year-old submariner had neutralized the Cubs’ right-handed-heavy lineup, which had led the majors in scoring (6.3 runs per game) by fanning a World Series-record 13 in the Game One victory.

Cubs skipper Joe McCarthy called on big Pat Malone to keep the Cubs’ championship hopes alive and shift the series back to the Windy City, where anything could happen. The big 26-year-old, 6-foot, 200-pound right-hander from Altoona, Pennsylvania, was arguably the NL’s best pitcher in 1929. After going 18-13 as a rookie, the hard-throwing Malone led the league with 22 victories, five shutouts, and 166 strikeouts, while his 5.6 strikeouts per nine innings paced the majors. He had been bombed in Game Two, yielding six runs (three earned) in 3⅔ innings and was collared with the loss. He was well rested, despite pitching two-thirds of an inning of relief in Game Four.

On a cloudy gray afternoon with temperatures in the 60s, Shibe Park, baseball’s first steel-and concrete ballpark, was filled with 29,921 spectators, including President Herbert Hoover.

Ehmke, who had made only eight starts in the ’29 regular season, wasn’t as sharp as in his Game One masterpiece. He yielded a hit in each of the first three innings and then got in a jam in the fourth after retiring the Cubs’ two most dangerous hitters, Rogers Hornsby and Hack Wilson. Following Kiki Cuyler’s double and Riggs Stephenson’s walk, Charlie Grimm and Zack Taylor connected for consecutive RBI singles to give the Cubs a 2-0 lead and knock Ehmke out of the game.

With the Cubs threatening to blow the game open, Mack called on Rube Walberg to put out the fire. The 32-year-old southpaw was one of Mack’s “Big Three” hurlers, along with Grove and George Earnshaw (24-8), on a staff that led the majors in ERA (3.44). Wahlberg (18-11) had paced the staff with 20 complete games, but had made only one shaky relief appearance thus far in the World Series. In Game Four he tossed one inning, permitted two inherited runners to score, and was charged with an unearned run.

Walberg “lost no time rescuing the sliding Athletics,” gushed Isaminger in the Philadelphia Inquirer.4 He quickly ended the frame by fanning Malone, the first of 10 straight Cubs he dispatched. In the seventh he retired the side on three pitches. Philadelphia sportswriter S.O. Grauley wrote Walberg was “pitching his arm off an using his head like a [Christy] Mathewson,” making a lofty comparison to “Big Six,” whose three straight shutouts in the 1905 World Series were the gold standard to measure postseason success.5

While Walberg held the Cubs to just two hits in 5⅓ scoreless innings to keep the Athletics in the game, Malone was tossing a “masterpiece,” wrote Isaminger.6 Through eight innings he had “tied the Mack clouters into a state of helplessness,” extolled Cubs beat writer Irving Vaughan.7 Malone had faced just 26 batters, yielding two hits, walking one, and benefiting from two double plays. In the fifth Jimmie Foxx reached on Hornsby’s error at second and moved up a station on Miller’s single, but Malone set down Jimmy Dykes and Joe Boley on popups.

Clinging to a precarious 2-0 lead, Malone punched out Walter French, pinch-hitting for Walberg to start the ninth. Hal Carlson (11-5 with a dismal 5.16 ERA) was warming up in the Cubs bullpen,8 but his services didn’t appear necessary with Malone “hurling fireballs with speed that dazzled the Mackian forces.”9 Quipped Philadelphia sportswriter John M. McCullough about the fans at Shibe Park, “the faint-hearted were toiling up the aisles towards the exits, apparently suffering from acute dyspepsia.”10

Those hopeless fans who left the park missed what is surely one of the most exciting and dramatic conclusions to any World Series. The vaunted A’s offense which had scored an AL-most 6.0 runs per game (tied with the Detroit Tigers) “suddenly turned on [Malone] and plastered his trappings,” reported Isaminger.11 Max Bishop, 3-for-20 in the Series thus far, singled to left to initiate a “current of heart pulsing and sturdy base blows,’ wrote Isaminger, which “lifted [the A’s] from the gutter to the purple raiment of the anointed.”12

To the plate stepped Mule Haas, mired in a 4-for-20 slump but one of the heroes of Game Four. His inside-the-park home run, which center fielder Hack Wilson lost in the sun, accounted for three runs in the A’s seventh-inning explosion. No slouch at the plate, Haas had batted .313 in the regular season and his 16 round-trippers ranked third on the club behind Al Simmons (34) and Foxx (33). Haas sent Malone’s first pitch to deep right field. “There was a strange silence as Cuyler backed against the fence as if he was going to catch the ball,” noted Vaughan.13 With one swing, the game was tied.

The rough-and-tumble Malone was livid. According to Grauley, he stomped to the plate and barked at his batterymate Zack Taylor about the pitch call.14 Malone returned to the mound where he was surrounded by his infielders, who offered words of encouragement and also discussed strategy with Mickey Cochrane, Simmons, and Foxx due up.

The inspirational leader of the Athletics, Cochrane battled Malone for six pitches, grounding out to second. Simmons, who had finished second in the AL with a .365 batting average, belted Malone’s second pitch off the scoreboard in right field for a double. Not wanting to take any chances, Malone intentionally walked the 21-year-old Foxx, who had emerged as one of baseball’s most dangerous sluggers.

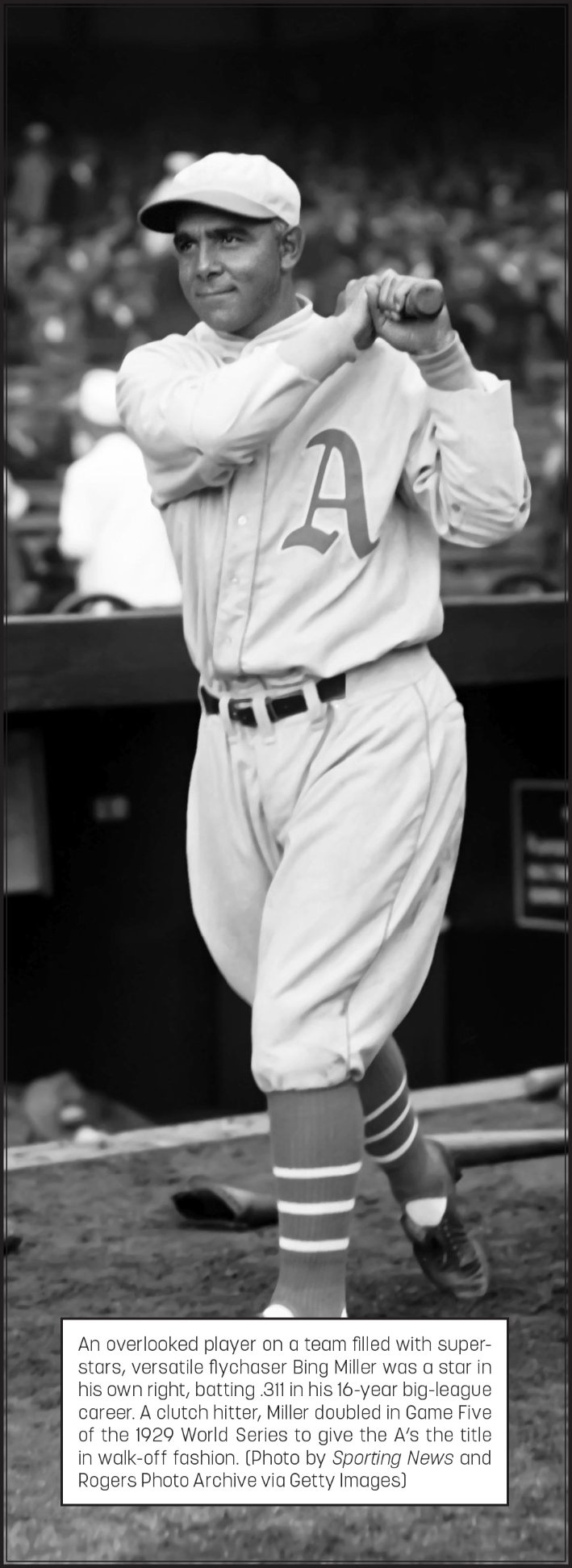

Bing Miller dropped the three bats he was swinging in the on-deck circle and dug in at the plate with the chance to be a hero. Historians can be forgiven for overlooking Miller on a team filled with superstars and Hall of Famers. A solid if unspectacular contributor, the 34-year-old Miller was coming off a season in which he batted .331, a few ticks higher than his then career .322 mark in nine seasons. Malone’s first pitch sailed high, followed by two straight over the plate, but Miller didn’t move his bat. “I took two strikes to wait for the ball I wanted,” said Miller.15 On Malone’s 22nd pitch of the inning and 112th of the game,16 Miller “drove [the ball] on a low, sweeping line” to right center, reported sportswriter John Drebinger.17 As Miller raced to second, Simmons easily scored the Series-winning run and ended the game in 1 hour and 42 minutes.

Pandemonium reigned as the A’s players celebrated near the mound and fans poured onto the field. “Paper by the ton had swirled through the stands and out onto the field,” reported McCullough.18

It was a stunning yet not unexpected victory for the 104-46 Athletics, who were heavy favorites entering the World Series. The electrifying late-game rallies lent the A’s an air of invincibility while the Cubs’ stunning, soul-crushing collapses contributed to what would emerge as a reputation for flopping on the biggest stage in baseball and losses their next four World Series (1932, 1935, 1938, and 1945). The A’s pitching staff thoroughly dominated the Cubs hitters, limiting them to just 17 runs (12 earned), a .249 batting average, and just one home run. They also struck out a then World Series record 50 batters.

Connie Mack became the first big-league manager to win four World Series championships. It was his first since his Deadball Era dynasty anchored by the “$100,000 infield” captured four pennants and three titles in a five-year span (1910-1914).19 This new dynasty, which would win three straight pennants, and another championship in 1930, would stake its claim as one of the best teams in baseball history.

SOURCES

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, SABR.org, and The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record.

Grauley, S.O. “What Happened to Every Pitched Ball as Athletics Slew Chicago Bruins,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 14, 1929: 24.

NOTES

1 Stan Baumgartner, “Connie in Tears, Hugs and Dances with Happy ‘Boys,’” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 14, 1929: 1.

2 James C. Isaminger, “Macks Win Games and Series; Hoover Is Thrilled as Hectic Rally in 9th Beat Cubs, 3-2,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 14, 1929: 1.

3 Baumgartner.

4 Isaminger.

5 S.O. Grauley, “Walberg Comes in to Make Cubs Lay Their Maces Down,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 14, 1929: 23.

6 Isaminger.

7 Irving Vaughan, “Macks Wins, 3-2; They’re World Champions,” Chicago Tribune, October 15, 1929: 31.

8 John M. McCullough, “Pandemonium Grips Hopeless Fans as A’s Crash Through,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 15, 1929: 1.

9 Grauley.

10 McCullough.

11 Isaminger.

12 Isaminger.

13 Vaughan.

14 Grauley.

15 Baumgartner.

16 Isaminger.

17 John Drebinger, “Athletics Win Title; 3 Run Rally in Ninth Beats Cubs, 3-2,” New York Times, October 15, 1929: 1.

18 McCullough.

19 The $100,000 infield refers to Stuffy McInnis, Eddie Collins, Jack Barry, and Home Run Baker.

Additional Stats

Philadelphia Athletics 3

Chicago Cubs 2

Game 5, WS

Shibe Park

Philadelphia, PA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.