October 30, 1871: The first pennant race: Chicago White Stockings vs. Philadelphia Athletics

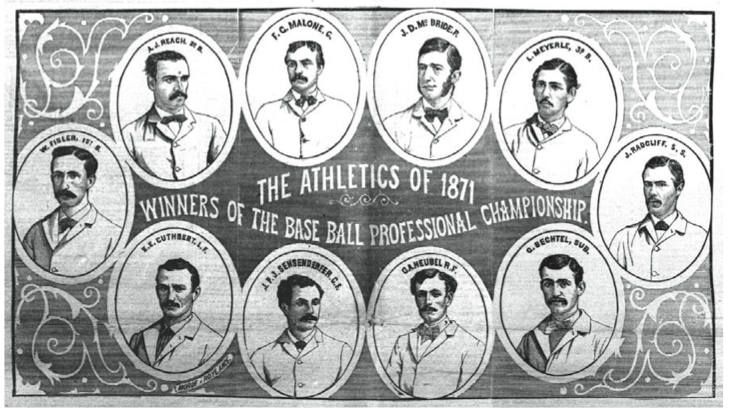

When the professional clubs met to form their own association in March of 1871, they resolved to scrap the old system of passing the “championship” from the nominal titleholder to a successful challenger and replace it with a season-end championship awarded to the best team. The winning club would then have the right to fly a “championship streamer” until the end of the following season. This made the 1871 season of the National Association baseball’s first pennant race. No club was more desirous of this change than the Athletic Club of Philadelphia, which had a strong team led by pitcher and Captain Dick McBride and had been denied a shot at the championship several times in the past five years.

Rules were adopted requiring contending teams to send in an entry fee before May 1, with championship games to be played before November 1. Each club was to play each other contender in a “best three in five games” series, with “the first games played to be the championship series unless otherwise stated in writing” (meaning each club could claim no more than three victories in each series). The club “winning the greatest number of games” in these series would be declared champion by the National Association’s championship committee. In case of a tie, the committee would examine the records of the tying teams and award the pennant to the team “with the best average in championship contests” (i.e., with the best winning percentage).1

It was widely assumed that one team would win all its series and therefore have the most wins and be champion. But as that first season neared its end, the Boston Red Stockings had lost their series against the Chicago White Stockings, the White Stockings had refused to play the Haymakers of Troy and had split their first four games against the Athletics of Philadelphia. The Athletics, meanwhile, had lost their series against Boston. The situation was further complicated by the Great Chicago Fire of October 8, which destroyed the White Stockings’ ballpark and the homes of most of its players. The White Stockings, desperate for cash, decided to play in Troy after all, splitting two games, before arranging to finish their series against the Athletics at the neutral Union Grounds in Brooklyn on October 30. Although there were still unresolved questions concerning some games, the most reliable figures showed Boston with 22 wins and 10 (or maybe 9) losses, the Athletics with 21 wins and 7 (or 9) losses, and Chicago with 19 wins and 8 losses.

Neither team was at full strength. The Athletics arrived without second baseman Al Reach and center fielder John Sensenderfer, necessitating several shifts in positions. Wes Fisler was moved from first base to second, George Heubel came in from right field to first, and utilityman George Bechtel was stationed in center. Veteran Tom Pratt was on the card to play in right field, but he was also absent, forcing the captain, Dick McBride, to press 40-year-old Nate Berkenstock, a well-known Philadelphia amateur, into service. This “Old Reliable” veteran did some outstanding fielding in the only professional action of his career. The Chicago squad was also short, since neither third baseman Ed Pinkham nor outfielder/change catcher Mart King had made the trip east. Young Mike Brannock played third base, and although the scorecard listed “Pinkham” at second base, Captain Jimmy Wood was there at his usual station. The White Stockings had lost their uniforms in the fire and each man wore a different set of borrowed shirts, pants, socks, and hats for this game.

Neither team was at full strength. The Athletics arrived without second baseman Al Reach and center fielder John Sensenderfer, necessitating several shifts in positions. Wes Fisler was moved from first base to second, George Heubel came in from right field to first, and utilityman George Bechtel was stationed in center. Veteran Tom Pratt was on the card to play in right field, but he was also absent, forcing the captain, Dick McBride, to press 40-year-old Nate Berkenstock, a well-known Philadelphia amateur, into service. This “Old Reliable” veteran did some outstanding fielding in the only professional action of his career. The Chicago squad was also short, since neither third baseman Ed Pinkham nor outfielder/change catcher Mart King had made the trip east. Young Mike Brannock played third base, and although the scorecard listed “Pinkham” at second base, Captain Jimmy Wood was there at his usual station. The White Stockings had lost their uniforms in the fire and each man wore a different set of borrowed shirts, pants, socks, and hats for this game.

Although the Philadelphia Press wrote that “no other event in the baseball world has attracted so much attention as this (game),”2 only about 600 fans were in attendance despite favorable weather. The game “in all respects, was one of the best of the season,” and “the pitching was the finest ever seen on the grounds and elicited appreciative applause and comments even from the veteran Chadwick.”3

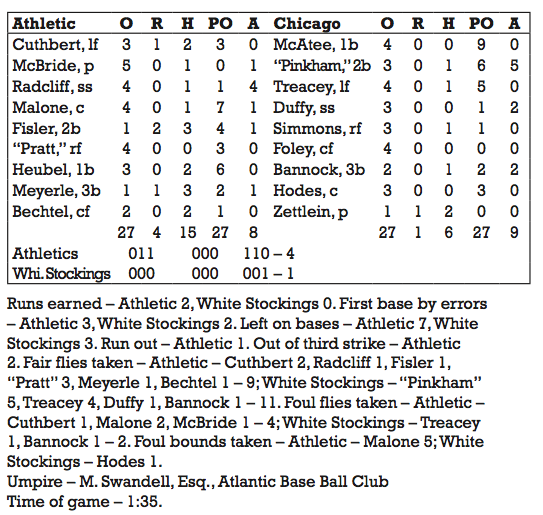

McBride lost the toss, and the Athletics made the first blank, followed by the White Stockings. In the second inning Fisler opened with a safe hit and moved around on a dropped third strike, an infield out, and a wild pitch. After another zero for Chicago, Ned Cuthbert scored in the third inning, reaching when his hot shot to shortstop was muffed, advancing on a single to short left by McBride, and scoring when pitcher George Zettlein threw past first base after fielding a grounder.

Nicknamed “The Charmer” because of his deceptive changes in speed and his ever-present smile, Zettlein settled down and blanked the Athletics through the next three innings. But McBride was pitching even better ball, his speed handcuffing the Chicago hitters. With the aid of two fine catches by Berkenstock, the Philadelphians led 2-0 through six innings. A hit up the middle by Levi Meyerle, a two-baser to left by Bechtel, and a useful ground out by Cuthbert added one to the Athletic ledger in the seventh inning. One-base hits by Wes Fisler, Heubel, and Meyerle brought in another run in the eighth.

As the game entered the ninth inning, the possibility of a “Chicago” game (i.e., a shutout) piqued interest. However, the White Stockings avoided a whitewash when Zettlein was able to reach second base on a double error and was allowed to score while the next two hitters were disposed of at first base. When Fred Treacey flied out to Berkenstock, ending the game as a 4–1 Athletic victory, “The assemblage broke forth in one wild shout which was very generally joined in by the Philadelphia players.”4

“The whip pennant belongs to the Quaker City,” the Philadelphia Press crowed, and “all festive Philadelphians will congratulate themselves.”5 As expected, three days later the National Association’s Championship committee ruled favorably about some disputed games and ended with a toast to Athletic president James N. Kerns (“To the president of the championship club”), who in turned raised his glass to the team’s captain and proposed “the health of Jonathan Dickson McBride.”6 After half a decade of frustration, Dick McBride and the Athletics were finally, definitively champions.

Notes

1 New York Clipper, March 25, 1871.

2 Philadelphia Press, October 31, 1871.

3 Philadelphia Press, October 31, 1871.

4 New York Herald, October 31, 1871.

5 Philadelphia Press, October 31, 1871.

6 New York Clipper, November 11, 1871.

Additional Stats

Philadelphia Athletics 4

Chicago White Stockings 1

Union Grounds

Brooklyn, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.