October 5, 1908: Ed Walsh beats Detroit for his 40th win, keeping Chicago’s pennant hopes alive

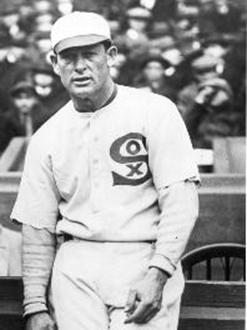

In the twentieth century only two pitchers recorded 40 or more wins in a season. Jack Chesbro accomplished the feat for the 1904 New York Highlanders, finishing the year 41-12. Ed Walsh joined him on that plateau by tallying 40 wins for the Chicago White Sox in 1908. His 40th win was a 6-1 triumph over the Detroit Tigers on October 5, the day before the season ended. Walsh not only reached a remarkable personal milestone, but he also kept the White Sox in pennant contention, setting up a dramatic one-game confrontation with the Tigers the next day to determine the American League champion.

In the twentieth century only two pitchers recorded 40 or more wins in a season. Jack Chesbro accomplished the feat for the 1904 New York Highlanders, finishing the year 41-12. Ed Walsh joined him on that plateau by tallying 40 wins for the Chicago White Sox in 1908. His 40th win was a 6-1 triumph over the Detroit Tigers on October 5, the day before the season ended. Walsh not only reached a remarkable personal milestone, but he also kept the White Sox in pennant contention, setting up a dramatic one-game confrontation with the Tigers the next day to determine the American League champion.

The 1908 AL pennant race was a three-way struggle between the defending champion Detroit Tigers, the Chicago White Sox, and the Cleveland Naps. As dawn broke on October 4, any one of the three had the chance to emerge as league champion and advance to the World Series. Detroit (89-61) held a 1½-game lead over Cleveland (88-63), and led Chicago (86-63) by 2½. The White Sox were hosting the Tigers the final three days of the season, while the Naps traveled to St. Louis for three games with the fourth-place Browns.

On October 4 Chicago beat Detroit 3-1, while Cleveland and St. Louis tied, 3-3. Because they tied, the Naps and Browns scheduled a doubleheader for October 5, to be followed by one last tussle the day after.

Even though the White Sox had not held first place since June 24, the team could snatch the pennant if it beat the Tigers twice more, and Cleveland faltered in at least one of its three contests with the Browns. Following that script, Chicago would ascend to first place with a winning percentage of .586, edging Cleveland’s .584 and Detroit’s .582.

No one should have been surprised when Chicago’s player-manager, Fielder Jones, entrusted the White Sox’ hopes to Walsh (39-15). The big right-handed spitballer had been on the mound to start seven of Chicago’s last 14 games. Walsh had proved his mettle by completing all seven games and winning five of them, including both games of a doubleheader against Boston on September 29. The Tigers countered with rookie knuckleballer Ed Summers (24-11), their winningest pitcher.

This was Walsh’s second attempt to notch his 40th win. On October 2 in Cleveland, he pitched brilliantly, striking out 15 Naps while surrendering just four hits and one run — only to turn up on the wrong side of history. Cleveland’s Addie Joss retired all 27 White Sox batters — a rare perfect game — to beat Walsh, 1-0.

Before the October 5 game, neither the Chicago Tribune nor the Detroit Free Press mentioned Walsh’s opportunity for his 40th win of the season. Rather, their stories focused on possible pennant outcomes. Likewise, although Walsh’s performance was lauded after he beat Detroit, neither newspaper informed its readers that Walsh had registered win number 40. Instead, glory was heaped on the team: “Jones’ bulldogs, who were fully conscious of the fact defeat meant oblivion for 1908, yet apparently were as confident of victory as if they were playing a high school nine.”1

On game day there was a “riot of rooting” by the Chicago crowd, which “used all available space and overflowed in the outfield.”2 Early in the contest, the teams and fans learned of St. Louis toppling Cleveland 3-1 in their first game. That outcome eliminated the Naps from the pennant race and raised the stakes at South Side Park.

It was obvious from the first pitch that only another fluke would beat Walsh. He “started like a whirlwind,”3 striking out the first two Tigers on just six pitches, before Sam Crawford flied out to finalize a toothless Tigers first. By the end of the fifth inning, Walsh added four more strikeouts, and only Ty Cobb’s second-inning bunt single marred his performance.

Chicago opened the scoring against Summers in a wild second inning. George Davis singled and went to third when Freddy Parent doubled over the left fielder’s head. Billy Sullivan singled to left, scoring Davis, and he continued to second when Matty McIntyre threw home to nip Parent at the plate. Lee Tannehill singled hard to right, but Cobb grabbed the ball and fired it home, freezing Sullivan at third. Catcher Charles “Boss” Schmidt took Cobb’s throw and whipped it to second, where Donie Bush tagged Tannehill short of the bag. Walsh grounded into the third out, so four consecutive hits netted Chicago just one run.

The White Sox pulled away in the bottom of the fourth. A hit batsman and single put runners on first and second. Sullivan lined a single to center; the ball rolled through Crawford and nearly into the crowd, allowing both runners to score and Sullivan to reach third. Crawford was charged with an error, and Sullivan had his second and third runs batted in of the afternoon. After an out, Sullivan scored on Walsh’s sacrifice fly, giving Chicago a 4-0 lead.

The White Sox tallied another run in the fifth frame when Jones singled, was bunted to second, and, after a second out, was singled home. Summers finished the inning — his last — having allowed five runs on nine Chicago hits, many of them line drives.

Trailing 5-0, Detroit broke through in the sixth with its only run. Red Downs lined a single to left. George Mullin, who pitched the final three innings, batted for Summers and fanned. McIntyre singled to right, sending Downs to third. Bush grounded to shortstop Parent, who threw wide of second base. Davis was able to keep his foot on the bag, stretch his full length, and catch the ball with his bare hand to force McIntyre, but Downs scored on the play. Crawford grounded out to Davis, and Detroit’s best inning ended with just one runner crossing the plate.

Ed Hahn singled to start Chicago’s half of the seventh. With two outs, Hahn stole second base, and he scored the White Sox’ sixth and final run when Patsy Dougherty bounced a single up the middle.

In the eighth, a hit batsman and single put Tigers on first and third with two outs, but Walsh’s ninth strikeout stopped that rally. Walsh walked Crawford to begin the ninth, but Cobb’s grounder forced Crawford at second, and two more groundouts closed the scorebook.

With the 6-1 win, Chicago remained in championship contention. Since the Browns had eliminated the Naps, it set up a winner-take-all battle between Chicago and Detroit on the final day of the season.

The Tigers immediately named Wild Bill Donovan (17-7) to start the deciding game, but Chicago’s Jones was unsure of his pick. He told reporters he might pitch Doc White or Frank Smith, or perhaps send Walsh to the mound one more time. Walsh had just pitched his sixth game in nine days, but even so, “the big fellow said he felt no ill effects in his arm from the tremendous amount of work it has done.”4

In the end, Detroit defended its crown — Donovan hurled a two-hitter — by routing error-prone Chicago, 7-0. White started and lost, lasting only one-third of an inning. Walsh relieved him, but in 3⅔ innings of work, he was of little help, serving up three runs on five hits. Since Cleveland won its final two games, the loss dropped the White Sox to third place.

In the nineteenth century, when basic rules and strategies of the game were in flux, pitchers won 40 or more games in a single season on at least 35 occasions.5 In that era, teams often relied on just one or two starting pitchers during an entire season. Typical of the period, the National League pennant-winning 1880 Chicago White Stockings called on pitcher Larry Corcoran (43-14) to start 60 times and Fred Goldsmith 24 times; two others chipped in a game apiece. In 1885 Chicago relied on John Clarkson to start 70 of its games — he won 53 — as it topped the National League with an 87-25 record.

Another 40-game winner is unlikely. Chesbro made 51 starts, and entered four more games in relief, winning three. Not only did Walsh make 49 starts, he registered a 5-1 record in 17 relief assignments. Both men logged more than 450 innings.6 No pitcher today is worked so hard. Modern teams often employ a five-man starting rotation, and have a separate relief staff. That results in fewer innings pitched, and a lesser number of pitching decisions. In 1908 Walsh won or lost 36.2 percent of his team’s games (55/152). In 2002, when Randy Johnson led the National League with 24 wins, he threw 260 innings, and was credited in only 17.9 percent of the Diamondbacks’ contests (29/162).

Sources

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/CHA/CHA190810050.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1908/B10050CHA1908.htm

1 I.E.Sanborn, “Sox and Tigers to Battle for Flag,” Chicago Tribune, October 6, 1908: 8.

2 Joe E. Jackson, “Better Hitting, Not Fielding, Wins No. 2 For the White Sox,” Detroit Free Press, October 6, 1908: 1.

3 Sanborn.

4 “Notes of the White Sox,” Chicago Tribune, October 6, 1908: 8.

5 Seven times from 1876-79; 26 times in the 1880s (including three seasons of 50 or more wins); and twice in the1890s, although none after the pitching distance was increased from 55 feet 6 inches to 60 feet 6 inches after the 1892 season. See Lyle Spatz, ed., The SABR Baseball List & Record Book (New York: Scribner, 2007). Other sources indicate the milestone may have been reached as many as 40 times.

6 Chesbro threw 454⅔ innings; Walsh, 464.

Additional Stats

Chicago White Sox 6

Detroit Tigers 1

South Side Park

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.