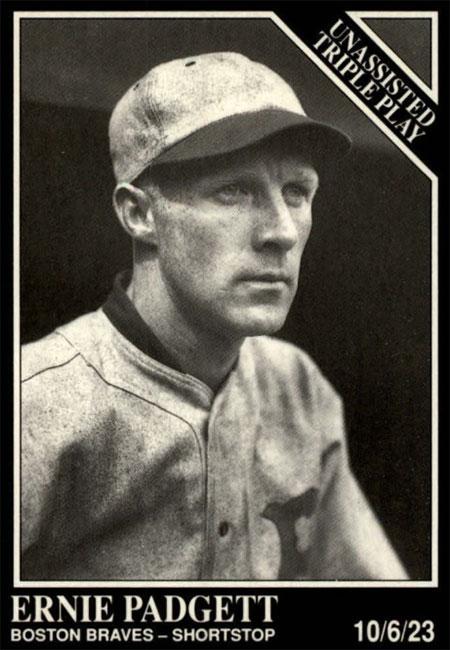

October 6, 1923: Ernie Padgett’s unassisted triple play

In 1923, the National League Braves and the American League Red Sox, besides sharing the city of Boston, had a couple of other notable things in common. One was that they both had truly awful seasons. With a record of 61-91, the Red Sox finished at the bottom of the junior circuit, 37 games behind the pennant-winning Yankees. The Braves sported an even worse record, 54-100, winding up 42 games off the pace, but were spared the ignominy of a last-place finish by defeating their rivals for the NL cellar, the Philadelphia Phillies, on the final day of the season.

In 1923, the National League Braves and the American League Red Sox, besides sharing the city of Boston, had a couple of other notable things in common. One was that they both had truly awful seasons. With a record of 61-91, the Red Sox finished at the bottom of the junior circuit, 37 games behind the pennant-winning Yankees. The Braves sported an even worse record, 54-100, winding up 42 games off the pace, but were spared the ignominy of a last-place finish by defeating their rivals for the NL cellar, the Philadelphia Phillies, on the final day of the season.

The other noteworthy commonality was that both teams, in the final weeks of the campaign, turned a defensive trick that had happened only twice previously in the twentieth century.

More rare than a perfect game or a four-strikeout inning, the unassisted triple play requires not only a particular set of game situation circumstances (no outs and at least two runners on base), but also a serendipitous combination of luck and lightning reflexes. On the infield dirt of Braves Field, in the 155th game of the 1923 baseball season, a 24-year-old rookie shortstop found himself in the right place at the right time, and made the most of his opportunity.

Ernie Padgett, born March 1, 1899, in Philadelphia, had already played 122 games, batting at a .317 clip, for the Memphis Chicks of the Southern Association when he was summoned to “The Show” at the end of September 1923.1 He debuted October 3 with a late-inning pinch-hit appearance against the Brooklyn Robins, and then got the nod from manager Fred Mitchell to start the final three-game series against the Phillies.

On October 4 Padgett played second base and collected his first major-league hit, but the Braves were crushed, 10-2, by the Quaker City nine. Friday the 5th was an off day, and the season was scheduled to wrap with a Saturday doubleheader. Boston at this point was two games ahead in the standings, but a closing-day sweep by the Phillies would lock the teams in a tie for the cellar.

Weather conditions were less than favorable as a much smaller than normal crowd of Braves Field patrons took their seats for the twinbill. Ed Cunningham in the Boston Herald referred to “about 1000 frost-bitten customers,”2 and the Boston Globe noted, “The weather was cold and with an overcast sky most of the time. …”3

The fans got their money’s worth in the opener alone, as the two teams battled into extra innings, the veteran first-sacker Stuffy McInnis finally driving in the winning run for the Braves on a triple in the bottom of the 14th. Winning pitcher Jesse Barnes went the distance, while Padgett, playing shortstop, walked, scored a run, and participated in three double plays.

Because of the lengthy first game, the approaching darkness, and, no doubt, the unpleasant weather, an agreement was made between games that the second contest would go only five innings.4

Manager Mitchell, at the tail-end of a second straight 100-loss season at the Braves’ helm, but now assured of avoiding eighth place, let his regulars sit; Stuffy McInnis and left fielder Gus Felix were the sole representatives of the Braves’ first-stringers in the finale. Padgett started again at shortstop.

Rookie left-hander Joe Batchelder pitched for the Braves; it was to be his only major-league start. Another southpaw, Lefty Weinert, took his dismal 4-16 record to the mound for Art Fletcher’s Phillies.

In the bottom of the first, McInnis’s second triple of the day scored Felix, who had reached on a force out. Boston’s lead ballooned an inning later, Padgett and second baseman Jocko Conlon each singling and then scoring on a base hit by catcher Dee Cousineau.Cousineau himself came home two outs later on Felix’s safety.

Batchelder, meanwhile, kept Philadelphia off the board until the third inning, when Ralph Head, relieving Weinert, singled, went to third on Heinie Sand’s double, and then notched the Phillies’ only run on a sacrifice fly by Johnny Mokan.

The scoring in this abbreviated game was now over … but one flashing moment of incomparable brilliance remained.

Cotton Tierney led off the fourth for the Phillies. A fair slugger for a second baseman (top 10 in homers and extra bases in 1923), he singled to left and moved to second on Cliff Lee’s drive to right.

The potential tying run came to the plate in the guise of switch-hitting Walter Holke, who had been purchased by the Phillies from the Braves after the 1922 season and won the first-base job.Batting righty against Batchelder, Holke cracked a low liner in the direction of left field. The ball was snared “a few inches from the ground”5 by Padgett at short. Tierney, already racing for third, was easily doubled up as Ernie stepped on second base. “Without faltering an instant in his stride,”6 Padgett set his sights on Lee coming down from first. The startled runner attempted a quick retreat but Padgett ran him down in just “a couple of strides,”7 applying the tag, killing the Quaker rally, and completing the fourth unassisted major-league triple play of the twentieth century.

This was not the only instance of a miraculous defensive feat in Boston’s 1923 baseball season. Three weeks earlier, first baseman George Burns of the Red Sox had retired three Cleveland Indians single-handedly in the second frame of a 12-inning tilt at Fenway Park. Of course, as Paul Shannon pointed out in the Boston Post, Burns was “a seasoned veteran of a wealth of experience and perhaps might have had similar chances in his big league career before” – while the “recruit” Padgett was “entitled to even more credit for showing the quickness of thought and the lightning execution that this play developed.”8

The Boston Herald of October 7 reported that Padgett was the first shortstop to pull off such a play, but in fact, Neal Ball had been playing shortstop for Cleveland when he did it in 1909. Second baseman Bill Wambsganss, also of the Indians, in 1920 became the only man (as of 2016) to achieve the play in a World Series.

In 1925 another 24-year-old shortstop, Glenn Wright of the Pirates, accomplished the singular feat, and two years after that, the Tigers’ Johnny Neun and the Cubs’ Jimmy Cooney9 followed in the footsteps of the Burns-Padgett tandem — pulling off solo triple killings in the same season (in fact, on consecutive days, May 30 and 31, 1927). After these dazzling deeds of the ’20s, a drought of four decades ensued, not another unassisted triple play occurring in the major leagues until 1968, when Ron Hansen performed the feat for the Washington Senators.

As for the raw rookie who wrote his page in baseball history on October 6, 1923, Ernie Padgett never lived up to his early promise. He took over as starting third baseman in 1924 after Tony Boeckel died in a preseason auto accident. He logged 138 games, second highest on the Braves, who unfortunately could not escape a last-place finish this time around. But the man who led all Southern Association hitters in 1922 with a .333 mark batted a disappointing .255 in his only full major-league season, although he did boast the third-best fielding percentage among NL hot-corner men.

Never again a regular, Padgett assumed the role of utility infielder in 1925, toiling usually at second base when he did play. Whatever magic attached itself to the Pennsylvania native as a result of his wondrous rookie play, it had worn off by 1926 and Padgett was peddled to the Cleveland Indians, with whom he closed out his short major-league career on July 30, 1927.

This article appeared in “Braves Field: Memorable Moments at Boston’s Lost Diamond” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and Bob Brady. To read more articles from this book, click here.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed, the author relied on Retrosheet.org and Baseball-Reference.com.

http://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/BSN/BSN192310062.shtml

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1923/B10062BSN1923.htm

Notes

1 Boston Globe, October 7, 1923.

2 Boston Herald, October 7, 1923.

3 Boston Globe, October 7, 1923.

4 BostonPost, October 7, 1923.

5 Boston Herald, October 7, 1923.

6 Boston Globe, October 7, 1923.

7 Boston Globe, October 7, 1923.

8 Boston Sunday Post, October 7, 1923.

9 Jimmy Cooney was the older brother of pitcher-outfielder Johnny Cooney, a teammate of Padgett’s on the 1923 Braves. The elder Cooney wrapped up his big-league playing career with the Braves in 1928, a teammate of his younger brother.

Additional Stats

Boston Braves 4

Philadelphia Phillies 1

Braves Field

Boston, MA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.