October 7, 1867: Candy Cummings debuts the curve

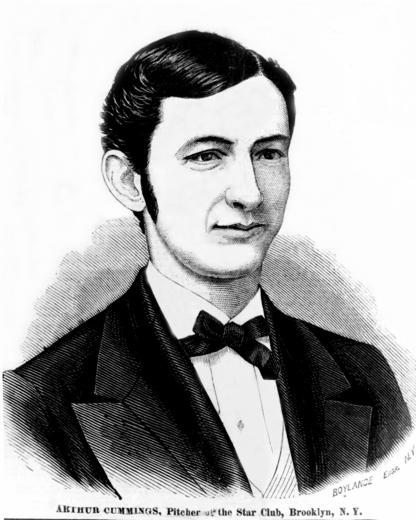

One of the oldest, most venerable weapons in the pitcher’s arsenal is the curveball. Various have been the claimants to its paternity, but the weight of the evidence falls upon a wispy fellow named William Arthur Cummings, known to posterity as Candy, a term of high approbation at the time of his rise to fame.

Growing up in the crucible of baseball that was Brooklyn in the 1850s and ’60s, Cummings first fixated upon the mechanics of objects curving in flight at the age of 14: “In the summer of 1863 a number of boys and myself were amusing ourselves by throwing clam shells and watching them sail along … turning now to the right, and now to the left. … All of a sudden it came to me that it would be a good joke on the boys if I could make a baseball curve the same way.”1

Growing up in the crucible of baseball that was Brooklyn in the 1850s and ’60s, Cummings first fixated upon the mechanics of objects curving in flight at the age of 14: “In the summer of 1863 a number of boys and myself were amusing ourselves by throwing clam shells and watching them sail along … turning now to the right, and now to the left. … All of a sudden it came to me that it would be a good joke on the boys if I could make a baseball curve the same way.”1

Four years of secretive experimentation and practice, with tantalizingly inconsistent results, ensued. Meanwhile, Candy climbed through the ranks of Brooklyn baseball, joining the powerful Excelsior club in 1866. The following spring he replaced Asa Brainard as the team’s main pitcher. It was near the close of 1867 when his long woodshedding came to fruition.

Consecutive losses to the Keystones of Philadelphia and Lowells of Boston on October 2 and 4 may have hinted to the Brooklyn ace that it was time to pull the rabbit out of his hat. But the decisive impetus came in the form of a hard-hitting catcher named Archie Bush.

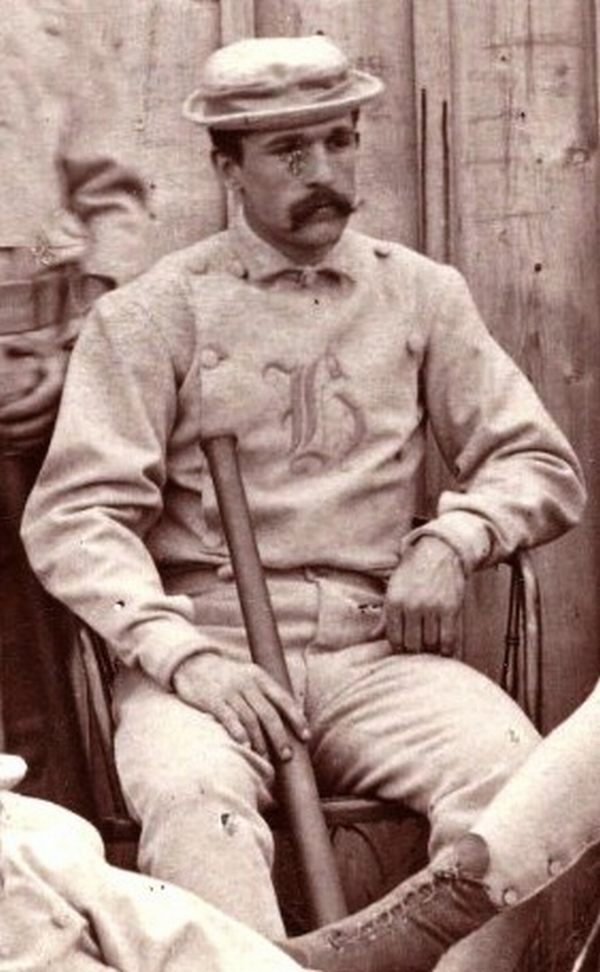

Long before facing Candy Cummings, Archibald McClure Bush had been tested on a real battlefield, having entered service in the Civil War in October 1863, just shy of his 17th birthday.2 After the war ended in 1865, Bush played with the Knickerbocker club of his hometown, Albany, New York. Still but a teenager, he entered prestigious Phillips Academy, a prep school in Andover, Massachusetts, in the fall of 1865,3 and is credited with organizing their first official baseball team.4

A sparkling career at Phillips Andover came to a sudden, ignominious end in May 1867 when Archie and a fellow senior cut classes to attend a ballgame in Boston and were summarily expelled.5 Undeterred, Bush crammed over the summer for Harvard’s exams and won admittance for the fall term.6 He debuted with the Harvard first nine on September 21, homering and picking off a runner who had carelessly strayed from second base.7

Jarvis Field was Harvard’s new athletic grounds, in use for only about four months when the Excelsior club met the collegians there on October 7, 1867. A small clubhouse sat a hundred feet behind home plate, the spectators’ seats forming a semicircle extending from either end of the clubhouse. The seating capacity was at least 5,000.8

Harvard scored a run in the first inning; Bush, batting fifth, likely made his initial plate appearance then. Cummings faced him with some trepidation, as he would confess to The Sporting News in 1892: “I was afraid of his prowess with the bat.”9 So it was that the 120-pound hurler decided to unleash his secret weapon. Here is his own clinical description:

“Snapping the ball with a wrist movement and getting it to spin through the air caused an air cushion to gradually form around the ball, gradually throwing the sphere out of a true course and turning it in the direction of the least resistance.”10

The result?

“When he struck at the ball it seemed to go about a foot beyond the end of his stick. I tried again with the same result, and then I realized that I had succeeded at last.”11

Here was affirmation for the long years of preparation.

“A surge of joy flooded over me that I shall never forget.… I said not a word, and saw many a batter at that game throw down his stick in disgust. Every time I was successful I could scarcely keep from dancing with pure joy.”12

A unique victory, with longstanding implications, had been won. But this day’s battle was not to go the Excelsiors’ way, for the pitch was still not fully harnessed:

“There was trouble. … I could not make it curve when I wanted to. … With a wind against me I could get all kinds of a curve, but … the ball was apt not to break until it was past the batter.”13

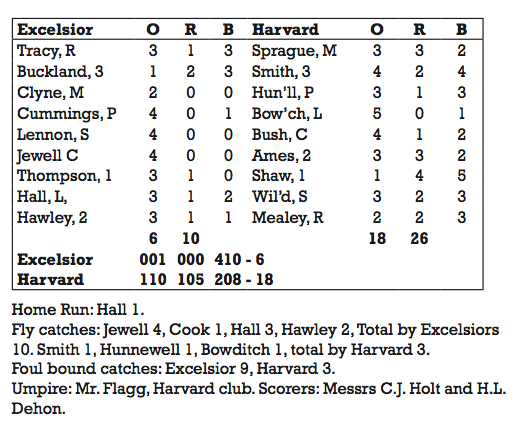

The Excelsiors trailed 3–1 by the end of the fourth. They “batted fairly” but their opponent’s infield formed “an impenetrable wall, against which ground balls were struck in vain.”14 The college boys found enough pitches to their liking and heaped on 15 runs in the last four innings. The final score was 18-6 in Harvard’s favor.

Nonetheless, one may glean some trace of Cummings’ triumph. In two games before and two games after the Excelsior match, Bush tallied 23 runs, seven homers, and only nine outs; against Cummings: four outs and one run.

Nonetheless, one may glean some trace of Cummings’ triumph. In two games before and two games after the Excelsior match, Bush tallied 23 runs, seven homers, and only nine outs; against Cummings: four outs and one run.

Cummings persevered and in due time mastered the magical pitch. He averaged 31 wins in his four (1872–75) National Association seasons and placed in the top 10 in strikeouts in all six of his NA and National League campaigns. These impressive statistics and, of course, his curve discovery, secured him a place in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

And what of the man who induced the first competitive curveball to be propelled plateward — the slugger who so spooked Candy Cummings that the spindly hurler finally unveiled his mystery pitch?

Archie Bush should have been a star in the major leagues as he had been in prep school and college, but in fact, he did not enjoy even the brief professional career of his adversary. Graduating from Harvard in the spring of 1871, he umpired two early season National Association games in Boston. Before year’s end he was employed with the Troy Car Works, a railroad car manufacturer. He married Margaret Boyd of Albany in October 1877 and the couple embarked on a honeymoon cruise to Europe. In December, with his wife already pregnant with a son, Archie Bush died of typhoid pneumonia in Liverpool, four weeks after turning 31.15

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Notes

1 Cummings, William Arthur. “How I Pitched the First Curve,” Baseball Magazine, August 1908, p. 21.

2 Eighth Report of the Secretary of the Class of 1871 of Harvard College (Boston: Press of Rockwell and Churchill, September 1896), p. 27.

3 Harrison, Fred. “Athletics For All,” at http://www.pa59ers.com/library/Harrison/Athletics02.html.

4 “Nine Inductees Selected for Athletics Hall of Honor,” May 7, 2010, at http://www.andover.edu/About/Newsroom/Pages/NineInducteesSelectedforAthleticsHallofHonor.aspx

5 Fuess. Claude M. An Old New England School, Chapter XIV, at http://www.ourstory.info/library/5-AFSIS/Fuess/school5.html. The ballgame in question was most likely that of Wednesday, May 15, between Harvard and Lowell of Boston. See also “Abby Locke’s Splendid Days: A Teenager’s Diary in 1860s Andover” at http://andoverhistorical.org/blog/.

7 The Harvard Advocate, Cambridge, Massachusetts, October 8, 1867, Vol. IV, No. 1, p. 10.

8 King, Moses. Harvard and Its Surroundings (Boston: Franklin Press: Rand, Avery, and Company, Boston, 1878), p.45.

9 “Curved Balls,” The Sporting News, February 20, 1892.

10 Murnane, Tim. “First Master of the Curve Ball,” Boston Daily Globe, January 14, 1906, p. SM3.

11 The Sporting News, February 20, 1892.

14 The Harvard Advocate, p. 25.

15 Eighth Report of the Secretary of the Class of 1871 of Harvard College.

Additional Stats

Harvard College 26

Excelsior of Brooklyn 10

Jarvis Field

Cambridge, MA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.