October 7, 1920: Sherry Smith stymies Cleveland bats in Game 3

Acrowd of just over 25,000 filed into Ebbets Field in Brooklyn for Game Three of the 1920 World Series. Others piled onto the rooftops of nearby houses along Bedford Avenue and Montgomery Street.1 “The fans turned out in droves,” wrote the New York Times, “and long after the game started thousands were left outside the gates waiting for a chance to elbow through the portals which led to the bleacher and pavilion seats. The aisles of the grandstand were jammed.”2

Acrowd of just over 25,000 filed into Ebbets Field in Brooklyn for Game Three of the 1920 World Series. Others piled onto the rooftops of nearby houses along Bedford Avenue and Montgomery Street.1 “The fans turned out in droves,” wrote the New York Times, “and long after the game started thousands were left outside the gates waiting for a chance to elbow through the portals which led to the bleacher and pavilion seats. The aisles of the grandstand were jammed.”2

The fans were passionate about their hometown Dodgers (or Superbas, Brooklyns, or Robins), champions of the National League, who had tied the best-of-nine series with the American League champion Cleveland Indians the day before. Cleveland’s bats had been silenced by the far from dominating yet solidly precise pitching of Burleigh Grimes, who shut out the Indians, 3-0. Cleveland’s astounding hitters (a .303 team batting average in the regular season), led by player-manager Tris Speaker, had batted a meager .190 (12-for-63) so far, leaving 10 runners on base in Game Two.

Brooklyn manager Wilbert Robinson’s team had played to its strengths. Brooklyn’s pitching staff had the best ERA (2.62) and most strikeouts (553) in the NL. Grimes led the way with a 2.22 ERA and 23-11 record. Led by Zack Wheat, Hi Myers, and Ed Konetchy, they could also hit with the best of them.

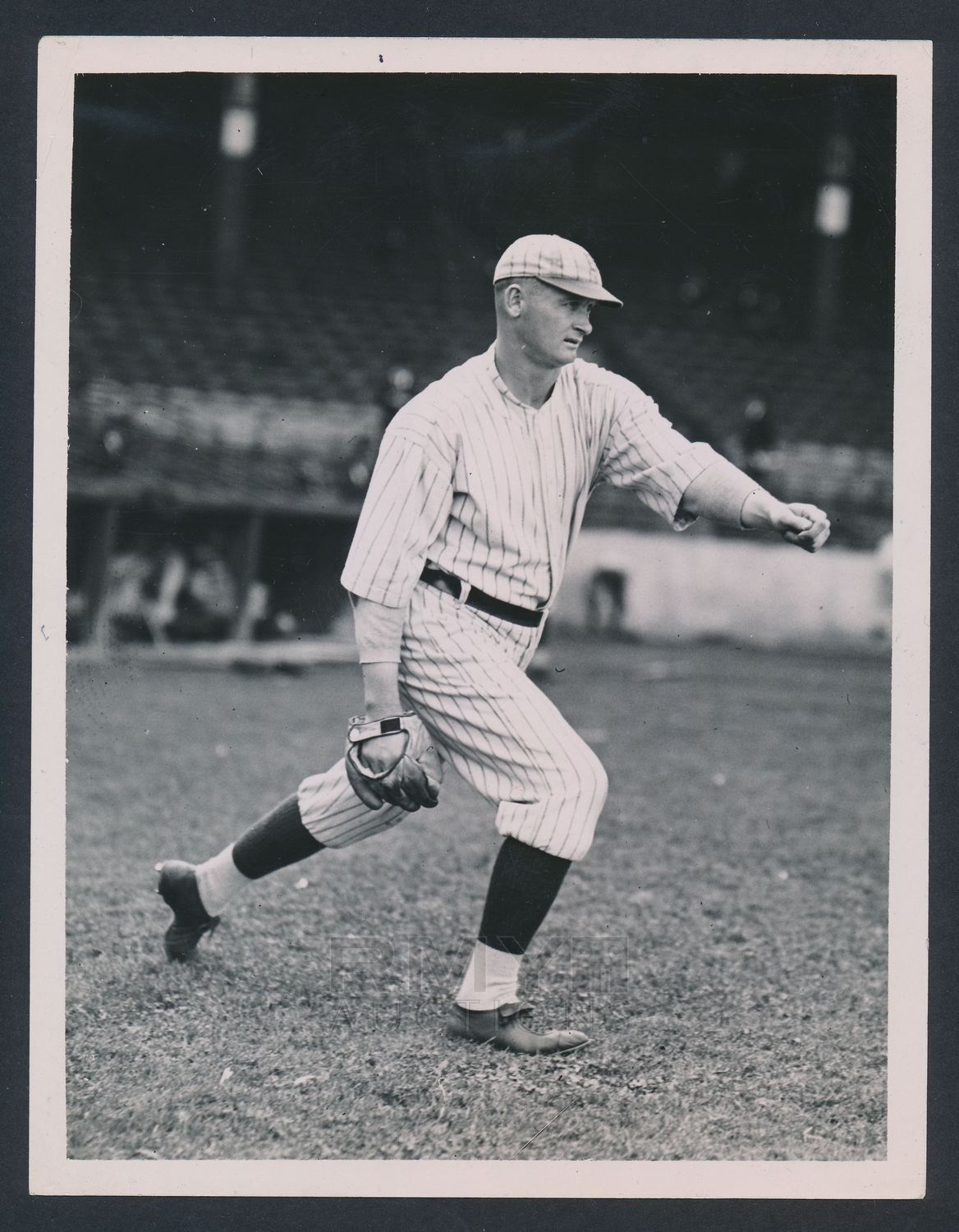

In Game Three, Sherry Smith (11-9, 1.85 ERA) took the hill for Brooklyn, while Ray Caldwell (20-10, 3.86) was a curious choice of Speaker. Despite a career-high 20 victories, Caldwell’s ERA was 4.97 from September on, while the newly reacquired Duster Mails went 7-0 down the stretch. But Caldwell had the experience while Mails was unpredictable, and Speaker went with the experience.

Hank O’Day, Bill Dinneen, Bill Klem, and Tommy Connolly were the umpires for the Series.

Despite walking Bill Wambsganss, Smith threw a scoreless first inning. It was a short day for Caldwell. He walked Ivy Olson “and some of the balls sailed so wide out that [catcher Steve] O’Neill had to jump on the infield carpet,” wrote Harry Cross of the Cleveland Plain Dealer.3 Jimmy Johnston sacrificed Olson to second. Shortstop Joe Sewell was playing in the shadow of the popular Ray Chapman, who had been killed after being hit in the head by a pitch from the Yankees’ Carl Mays on August 16. Sewell had struggled so far in the Series, and another “perilous moment,” Cross wrote, was upon “the little shortstop who has jumped from the bush league right into the nervous strain of the world’s series.”4 Sewell booted a grounder from Tommy Griffith, and Olson made it to third. Wheat singled to left, scoring Olson. Myers looped a hit off the glove of a leaping George Burns at first and Griffith scored. Speaker was impatient and jogged in from center to take out his starter. “Caldwell was a sorry figure as he walked to the bench,” Cross wrote. “The greatest chance of his baseball career had come and he had failed.” He lasted just one-third of an inning, and in came the lefty Mails, “one of those eccentric left-handers who is chock full of confidence.”5

Ed Konetchy popped up to second. Pete Kilduff launched a long fly ball in foul ground in “the deepest wildness of right field,” where a sprinting Smoky Joe Wood made a nice running catch.6 The former Red Sox pitching ace had reinvented himself as a dependable utility outfielder for Speaker, his old teammate. Mails had put out the fire in the first.

Smith didn’t allow a Cleveland hit through three innings and was the beneficiary of excellent defensive play by right fielder Tommy Griffith. In the second, Larry Gardner lined hard to right, but Griffith nabbed it on the run. Wood smashed one to deep right by the foul line and Griffith again ran it down. Griffith showed why he finished in the top 10 in fielding percentage, assists, putouts, and range factor for right fielders throughout his career. When the inning ended, Griffith ran to the bench amid the cheering fans who acknowledged his defensive prowess.

Mails walked leadoff man Otto Miller to begin the second. When Smith attempted to bunt Miller over, he popped it up and Mails did a whirling dance to snag it and whip a throw to first to double up Miller. Olson singled to center but was caught stealing to end the inning.

Robinson made a curious move in the bottom of the third by lifting defensive guru Griffith to avoid a lefty-lefty matchup with Mails. He sent up right-hander Bernie Neis to pinch-hit. Neis was no slouch defensively either, and had blazing speed. The percentages didn’t work this time and Neis grounded out. Mails surrendered a single to Wheat, but nothing further.

Smith benefited from yet another dazzling defensive play. In the fourth, Wambsganss rocketed a shot that third baseman Johnston was unable to spear going to his left. Shortstop Olson backed him up, picking the ball off the outfield grass and nailing the runner with a pinpoint throw. It was even more significant because of what happened next. Speaker launched a drive to left that Zack Wheat got in front of, but the ball took a weird bounce, went through his legs, and rolled into foul territory. Speaker made it all the way around the diamond in what was scored a double and an error on Wheat. The Indians would take it, considering that this was the first hit they managed against Smith.

With one gone in the fifth, Sewell walked. O’Neill singled to center and it looked as if Cleveland finally was getting to Smith. Mails ripped a liner to Olson, who flipped to second baseman Kilduff. Kilduff’s relay was wild but Konetchy laid flat out for the ball, keeping one toe on the base, to the roar of the crowd. “Man, sir,” exclaimed Thomas S. Rice of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. “That was a heap of a play!”7 The Dodgers got out of the jam. The crowd was equally appreciative of glovework by the opposition, applauding George Burns of Cleveland. In the sixth, the first baseman chased a foul popup near the box seats and “reached his hand over the heads of a box full of Brooklyn Society folk and nabbed the ball,” wrote the Plain Dealer’s Cross.8 Myers singled, but Mails was helped by another double play.

The best defensive play of the game may have come in the eighth inning. Mails had done his job for Tris Speaker with 6⅔ scoreless innings of relief and only three hits allowed. With one out and O’Neill at first, Speaker sent pinch-hitter extraordinaire Les Nunamaker to the plate. Nunamaker was a career .391 hitter in that role (36-for-92) but only 3-for-15 in 1920. He sent a sizzling grounder to Johnston at third, who started a perfect double play to Kilduff and “Koney” at first. “There’s the flashiest double play that the Dodgers ever executed,” someone in the crowd boasted as the multitudes were on their feet roaring yet again.9 “That play,” wrote Rice, “had not only to be without a flaw, but had to be put through without wasting time enough to blink an eye. It is safe to say that not one fan in ten at the diamondside thought Kilduff would get the ball to Koney in time.”10

George Uhle came out of the bullpen for Cleveland in the bottom of the eighth, just as he had in Game Two. He again pitched a scoreless frame.

Smith retired Cleveland in the ninth on three groundballs and put the finishing touches on a World Series masterpiece. He allowed only one run, which was unearned, and he had forced 18 batters to ground out. So far in the World Series, Cleveland’s mighty batting attack had been stymied by Brooklyn pitchers, who had allowed only one earned run. Cleveland now had a two-games-to-one lead in the series. The roar of the crowd at Ebbets Field was matched across the East River at the electronic scoreboard in Times Square, where an estimated 12,000 folks “solidly packed up to Forty-Fourth Street, and jammed both the east and west corners of Broadway.”11

At 9 o’clock that night, diehard Brooklyn fans turned out at Grand Central Station to send best wishes to their team on its journey to Cleveland. Fans were enthusiastic, believing their Dodgers would bring Brooklyn its first World Series title. “The cheers that answered the toots of the locomotive as it pulled out with the train conveying the Superbas made the spacious station appear to tremble,” wrote James J. Murphy in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle.12

The rest of the World Series would be much different in Cleveland, however, and those screaming fans would get used to uttering the phrase at Ebbets Field, “Wait ‘til next year.”

SOURCES

Besides the sources listed in the Notes, the author relied on statistical information from Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

NOTES

1 Al C. Palma, “Robins Outplay Indians in All Departments of Game,” Brooklyn Citizen, October 8, 1920: 4.

2 “Robins Win Third Game When Smith Baffles Indians,” New York Times, October 8, 1920: 1.

3 Harry Cross, “Brooklyn Drives Ray Caldwell from Box; Wins in First Inning,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 8, 1920: 19.

4 “Brooklyn Drives Ray Caldwell from Box; Wins in First Inning.”

5 “Brooklyn Drives Ray Caldwell from Box; Wins in First Inning.”

6 “Brooklyn Drives Ray Caldwell from Box; Wins in First Inning.”

7 Thomas S. Rice, “Superbas Rule Favorites as They Speed to Cleveland,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 8, 1920: 24.

8 “Brooklyn Drives Ray Caldwell from Box; Wins in First Inning.”

9 “Brooklyn Drives Ray Caldwell from Box; Wins in First Inning.”

10 “Superbas Rule Favorites as They Speed to Cleveland.”

11 “12,000 Watch Scoreboard,” New York Times, October 8, 1920: 15.

12 James J. Murphy, “Will Be Back with the Title, Say Superbas Traveling West,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 8, 1920: 1.

Additional Stats

Brooklyn Robins 2

Cleveland Indians 1

Game 3, WS

Ebbets Field

Brooklyn, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.