October 8, 1930: Earnshaw’s complete-game gem on one-day rest gives Athletics second straight championship

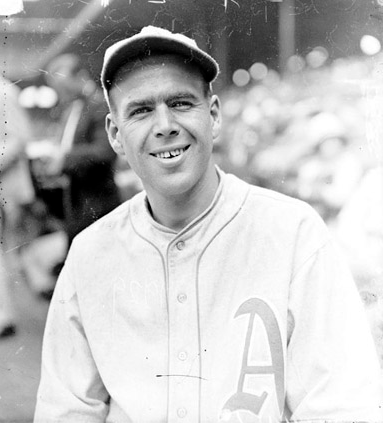

George Earnshaw “gave an exhibition of pitching mastery that has been seldom equaled in [the] world series,” declared St. Louis sportswriter John E. Wray.1 Pitching on one day’s rest, the Philadelphia Athletics hurler tossed a complete game to win Game Six and capture the club’s second straight title. Lauded as the “the lionhearted leviathan of the peak” by A’s beat writer James Isaminger, Earnshaw extended his Series scoreless streak to 23⅓ innings before yielding a ninth-inning tally in the resounding 7-1 victory over the Cardinals.2

George Earnshaw “gave an exhibition of pitching mastery that has been seldom equaled in [the] world series,” declared St. Louis sportswriter John E. Wray.1 Pitching on one day’s rest, the Philadelphia Athletics hurler tossed a complete game to win Game Six and capture the club’s second straight title. Lauded as the “the lionhearted leviathan of the peak” by A’s beat writer James Isaminger, Earnshaw extended his Series scoreless streak to 23⅓ innings before yielding a ninth-inning tally in the resounding 7-1 victory over the Cardinals.2

In his 50th year of baseball, owner-skipper Connie Mack’s A’s (102-52) ran away with the pennant, which sportswriter Grantland Rice considered a “wonder” given that the Tall Tactician “had only two dependable pitchers all year.”3 Those two – Earnshaw and Lefty Grove – proved to be an unconquerable combination. In the “Year of the Hitter,” pitching decided the Series. Grove won the Series opener, 5-2, followed by Earnshaw’s 6-1 victory in the second contest. After the Cardinals won a pair in the Gateway City, Earnshaw held the Redbirds scoreless on two hits through seven innings in Game Five before yielding to a pinch-hitter. Grove tossed two innings of relief and picked up the win on Jimmie Foxx’s dramatic two-run ninth-inning home run.

On the train ride from St. Louis back to the City of Brotherly Love, Mack approached Earnshaw and Grove about starting Game Six. Both hurlers volunteered to pitch. Grove (28-5) was baseball’s best pitcher, having paced the majors in wins, ERA (2.54 in 291 innings), and strikeouts (209); he was probably also baseball’s best closer – if there had been such a designation at the time – relieving 18 times among his big-league-most 50 appearances. Mack decided to go with Earnshaw and keep his ace ready in the bullpen with the option to start Game Seven, if needed. “In all my years in baseball,” said Mack, “I have never seen two pitchers more willing to work at all times than this master right-hander and this king of left-handers.”4

Grove’s dominance during the A’s dynasty has cast a shadow on Earnshaw, a hulking, 6-foot-4, 210-pound behemoth affectionately called Moose. In just his second full season in the majors, the 30-year-old hurler followed his 24-win campaign with a 22-13 slate, led the majors with 39 starts, and trailed only Grove in appearances (49) and strikeouts (193); his 4.44 ERA in 296 innings was below the major-league average (4.83), but he struggled with control, issuing a league-most 139 walks.

On a pleasant Wednesday afternoon with overcast skies and temperature in the 60s, Shibe Park was once again filled to capacity with 32,295 spectators.5 Several thousand more were sitting atop the row houses on 20th Street behind right field. Al Schacht and Nick Altock provided the crowd with pregame entertainment and baseball shenanigans.

Earnshaw “blazed through the Red Bird flock” in the first, wrote Philadelphia sportswriter S.O. Grauley, fanning two of the three batters he faced.6 Grove was already in the bullpen and stayed warm throughout the game.7 Skipper Gabby Street’s Cardinals (92-62) had led the NL with 1,004 runs while each member of their starting lineup batted at least .300, but the offensive juggernaut had scored just 11 runs in the first five Series games. Typically disciplined at the plate, the Cardinals were “swinging at everything” since the first game, an anonymous umpire told St. Louis sportswriter Sid Keener.8 Consequently, Earnshaw kept “his fastballs high on the outside and his curves low on the inside,” noted the arbiter, and the Cardinals failed to adjust.

The Cardinals staff finished second in the NL in team ERA (4.39), yet lacked a bona fide ace, like Grove or Earnshaw. Their best hope was hard-throwing 27-year-old right-hander Bill Hallahan, who emerged in his first full season in the majors to lead the staff in practically every category, including wins (15) and innings (237⅓), while also pacing the NL with 177 punchouts. Wild Bill also led the league in walks (126). In Game Three he blanked the A’s despite yielding seven hits and five walks.

After Jimmy Dykes drew a one-out walk in the bottom of the first, Mickey Cochrane lined a screeching shot to first base. According to Keener, Jim Bottomley leaped and “connected with the ball.”9 “Just for a moment it looked like Sunny Jim had a perfect double play” to end the inning, wrote Keener, but Bottomley couldn’t corral the ball, which flew into right field, through George Watkins’ legs for an error, and rolled to the wall. Dykes scored and Cochrane might have, reported Isaminger, but was held at third by coach Eddie Collins.10 The “ball game was lost” on Cochrane’s double, lamented Keener.11 After Al Simmons fanned, Foxx walked. Mired in a 1-for-18 slump, Bing Miller blasted a double to the scoreboard to plate Cochrane.

Earnshaw systematically dismantled the Cardinals, yielding just three hits and a walk through eight scoreless frames. His “speed was as blinding, his control excellent and his curve broke fast enough to befuddle the Missourians,” gushed Grauley.12 His effectiveness notwithstanding, Earnshaw was in excruciating pain, suffering from a deep stone bruise on his foot that he had aggregated in Game Five. According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, Earnshaw removed his shoe each inning so that the trainer could massage his foot.13 The foot agony didn’t bother his reflexes. In both the sixth and seventh innings, he snared bullets back to the mound, robbing what might have been hits from Andy High and Frankie Frisch, respectively. “Big George acted like a man who had snared a couple of hand grenades and was trying to be nonchalant about it,” quipped A’s beat writer George H. Dixon.14

While Earnshaw mowed down the Redbirds, the A’s vaunted offense, which trailed only the New York Yankees in scoring, kept swinging for the fences. Hallahan, who was pitching on three days’ rest, labored through the second, hitting Max Bishop with a pitch and walking Dykes, but escaped the jam. Nonetheless, he was removed from the game because a blister on the tip of his middle finger burst.15 “I had a little swelling of the finger before the game,” Hallahan admitted later.16

Al Simmons, who had led the AL with a .381 batting average while rapping 36 home runs and driving in 165 runs, led off the Athletics’ third inning with a towering blast into the upper deck in left field off reliever Syl Johnson to give the A’s a 3-0 lead. Isaminger described the shot as the “crack of doom to the Cardinals’ hopes of winning the game.”17

Bucketfoot Al’s long ball did, in fact, silence the crowd after its momentary eruption of euphoria wore off. Newspapers described the Philadelphia crowd as subdued. While Isaminger wrote that the spectators “sat through most [of the game] without one situation where there was uneasiness,”18 syndicated scribe Westbrook Pegler declared that there was “no suspense at any time,” and that the game “petered out instead of rising to a climax.”19

In the fourth with Bishop on via a walk, Dykes connected for a “bristling drive that screamed on a line straight into the left field stands,” wrote Isaminger, extending the A’s lead to 5-0. The dependable third baseman, who had entered the game mired in a 2-for-16 slump and was coming off two rough defensive games, was the hitting hero of this game, reaching base all four times on two hits and two walks, scoring twice, and knocking in two runs.

Emerging as baseball’s most feared slugger after Babe Ruth, Foxx (.335-37-156) doubled to open the fifth. The A’s reverted to “scientific baseball,” wrote Isaminger, as Miller executed a sacrifice bunt followed by Mule Haas’s deep fly out to drive in Foxx.20

The A’s scored their seventh unanswered run in the sixth off Jim Lindsey, who relieved Johnson to start the frame. Bishop walked and moved to third on Dykes’ doubles, and scored on Cochrane’s sacrifice fly.

Earnshaw took the mound in the ninth riding a streak of 22⅔ scoreless innings since yielding a one-out home run to Watkins in the second inning of Game Two. High led off with a single, followed by Watkins’ walk to bring the slumping heart of the Cardinals batting order to the plate. Frisch, who had scored 121 runs and knocked in 114 while batting .346, hit a screeching liner directly at Foxx who doubled up Watkins. The Fordham Flash concluded the Series without scoring or driving in a run. Chick Hafey (.336-26-107) connected for a double to left, driving in High. Bottomley (.304-15-97), whom St. Louis sportswriters derided as the biggest flop of the series for his dreadful 1-for-22 performance, walked. On his 24th pitch of the inning and 124th of the game, Earnshaw retired Jimmie Wilson on a fly ball to right field to end the game in 1 hour and 46 minutes.21

Earnshaw’s three-start performance was hailed as one of the best in the history of the World Series, even though he didn’t win three games as eight pitchers before him had done.22 His complete-game five-hitter with six punchouts and three walks pushed his Series totals to a 0.72 ERA in 25 innings, while surrendering just 13 hits and walking 7 while fanning 19. Grauley praised Eanshaw’s performance as the greatest World Series pitching since Christy Mathewson set the standard by pitching three shutouts for the New York Giants in 1905.23

The World Series in the Year of the Hitter, when big-teams produced a record .296 batting average and established new scoring records, unfolded as a showcase of pitchers. The A’s managed only seven hits in Game Six, but they all went for extra bases. In the Series, the A’s outscored the Cardinals 21-12; both teams batted well below their regular-season average (the A’s .197 down from .294 and the Cardinals .200, a far cry from their .314 average).

POSTSCRIPT

The A’s and Cardinals met for a rematch in 1931. While Mack fielded practically the same team, Street’s club was infused with some new talent, including the exciting catalyst Pepper Martin and rookie pitcher Paul Derringer. The final result shocked many and signaled the end of a dynasty.

SOURCES

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, SABR.org, The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record, and the following:

Haley, Martin. “Pitched Brilliantly in 3 Games, Winning Two and Sharing Honors in Third,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 9, 1930: 20.

Stockton, J. Roy. “Cardinal Southpaw Looked Better Than Ever at Start; Redbirds Fought All the Way,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 9, 1930: 28.

NOTES

1 John E. Wray, “Wray’s Column,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 9, 1930: 28.

2 James C. Isaminger, “Fifth Diadem Jauntily Atop Connie’s Head,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 9, 1930: 1, 20.

3 Grantland Rice, “The Sport Light,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 9, 1930: 21.

4 Connie Mack, “Connie Mack Proud of Fighting Aides; Praises Earnshaw,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 9, 1930: 21.

5 “Yesterday’s Local Weather Report,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 9, 1930: 2.

6 S.O. Grauley, “George’s Iron-Man Feat Just Short of Great Matty’s Mark,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 9, 1930: 22.

7 Babe Ruth, “Grove Pitches Nine Innings in ‘Bullpen,’” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 9, 1930: 28.

8 Sid Keener, “Sid Keener’s Column,” St. Louis Star and Times, October 9, 1930: 18.

9 Sid Keener, “Frisch, Bottomley and Hafey Drove in 1 Run in Series,” St. Louis Star and Times, October 9, 1930: 18.

10 Isaminger.

11 Keener, “Frisch, Bottomley and Hafey Drove in 1 Run in Series.”

12 Grauley.

13 Walter S. Cahill, “Footnotes of A’s-Cards Battle,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 9, 1930: 20.

14 George H. Dixon, “Macks Collect 7 Runs on 7 Hits to End Series,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 9, 1930: 1.

15 Stan Baumgartner, “Blister on Finger Forced Removal of Wild Bill Hallahan,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 9, 1930: 22.

16 Baumgartner.

17 Isaminger.

18 Isaminger.

19 Westbrook Pegler, “Calm Follows Storm in Final of Fall Classic,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 9, 1930: 20.

20 Isaminger.

21 Pitch count from Grauley. Earnshaw threw 124 pitches, of which 88 were strikes and 36 balls.

22 Those eight pitchers are Bill Dinneen (Boston Red Sox, 1903, 3-1 in 4 starts, 2.06 ERA in 35 innings), Deacon Phillippe (Pittsburgh Pirates, 1903, 3-2 in 5 starts, 3.07 ERA in 44 innings), Christy Mathewson (New York Giants, 1905, 3-0 with three straight shutouts), Babe Adams (Pittsburgh Pirates, 1909, 3-0 in 3 starts, 1.33 ERA in 27 innings), Jack Coombs (Philadelphia Athletics, 1910, 3-0 in 3 starts, 3.33 ERA in 27 innings), Smoky Joe Wood (Boston Red Sox, 1912, 3-1 in 4 games, 3 starts, and 4.50 ERA in 22 innings), Red Faber (Chicago White Sox, 1917, 3-1 in 4 games, 3 starts, 2.33 ERA in 27 innings), and in the best-of-nine 1920 World Series Stan Coveleski (Cleveland Indians, 3-0 in 3 starts, and 0.67 in 27 innings). Several other pitchers with at least three starts in the one World Series should be mentioned, though they did not win three games: George Mullin, Detroit Tigers, 1909 (2-1 in 4 games, 3 starts with 2.25 ERA in 32 innings); Chief Bender, Philadelphia Athletics, 1911 (2-1 in 3 starts, 1.04 ERA in 26 innings); Mathewson in 1911 (1-2 in 3 starts, 2.00 ERA in 27 innings), Lefty Tyler (Chicago Cubs, 1918, (1-1 in 3 starts, 1.17 ERA in 23 innings), Walter Johnson (Washington Senators, 1925, 2-1 in 3 starts with 2.08 ERA in 26 innings). The 1921 best-of-nine World Series featured four outstanding pitching performances: The New York Giants’ Phil Douglas (2-1 in 3 starts with 2.08 ERA in 26 innings) and Art Nehf (1-2 in 3 starts with 1.38 ERA in 26 innings) and the New York Yankees’ Waite Hoyt (2-1 in 3 starts, 0.00 ERA with 2 unearned runs in 27 innings) and Carl Mays (1-2 in 3 starts, 1.73 ERA in 26 innings),.

23 Grauley.

Additional Stats

Philadelphia Athletics 7

St. Louis Cardinals 1

Game 6, WS

Shibe Park

Philadelphia, PA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.