October 9, 1932: NFL’s Boston Braves return pro football to Beantown

As the 1932 National Football League season began, there was reason for excitement among Boston’s sports fans. Since the Boston Bulldogs folded after their lone season in 1929,1 Boston had been without an entry in the 12-year-old NFL. However, in July 1932, a syndicate headed by George Preston Marshall, a laundry tycoon from Washington, D.C., was awarded a team in Boston, and they joined the Chicago Cardinals, Chicago Bears, Staten Island Stapletons, Green Bay Packers, Brooklyn Dodgers, New York Giants, and Portsmouth Spartans to form a revamped league.2

As the 1932 National Football League season began, there was reason for excitement among Boston’s sports fans. Since the Boston Bulldogs folded after their lone season in 1929,1 Boston had been without an entry in the 12-year-old NFL. However, in July 1932, a syndicate headed by George Preston Marshall, a laundry tycoon from Washington, D.C., was awarded a team in Boston, and they joined the Chicago Cardinals, Chicago Bears, Staten Island Stapletons, Green Bay Packers, Brooklyn Dodgers, New York Giants, and Portsmouth Spartans to form a revamped league.2

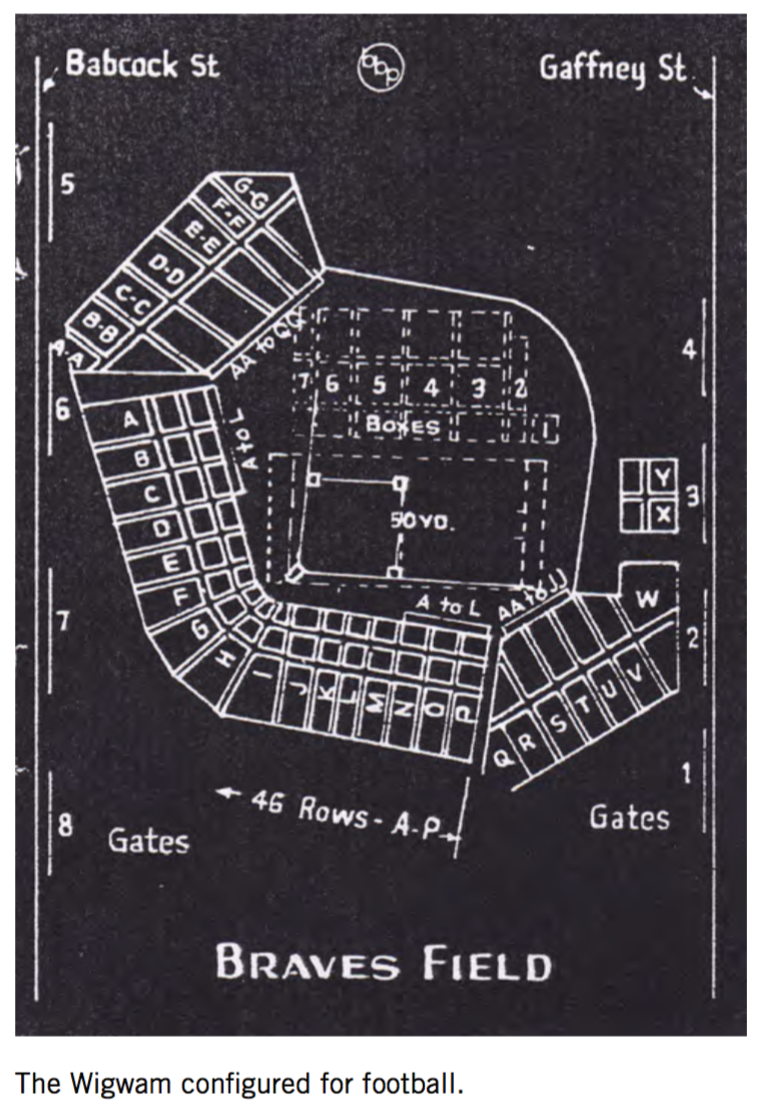

The new team cost the Marshall syndicate nothing; all the owners had to do was pay the operating expenses. (Seventy years later, Forbes magazine estimated the team’s value at $1.55 billion.3) As Marshall made marketing plans, he contracted with Boston’s National League baseball team, the Braves, for the use of their ballpark, Braves Field; and he also borrowed their name. In 1932 the Boston Braves joined the NFL.

To coach, Marshall hired J.R. Ludlow “Lud” Wray, a former University of Pennsylvania center who had played in the NFL during the early 1920s; and to sign players, the laundry king searched far and wide, sparing no expense. From Washington State University, he obtained for the lavish sum of $1,500 All-American tackle Albert Glen “Turk” Edwards, who had been sought by several NFL teams; from the University of Southern California, Marshall signed running backs Ernie Pinckert and Jim Musick; and from little -known West Virginia Wesleyan College, he recruited a dynamic runner named Cliff Battles. Both Edwards and Battles were later enshrined in the NFL Hall of Fame.

As the Braves roster began to take shape, the team held training camp in Lynn, Massachusetts, a couple of towns away from Boston, and played exhibition games around Boston; they defeated teams from Quincy and Beverly, but lost to the Providence Steam Roller, a former NFL entry, which featured several players previously cut by the Braves. Throughout, Marshall hyped the team, promising in Boston’s local dailies to provide quality football at bargain prices. He was true to his word, too, as ticket prices were 55 cents for the Braves Field bleachers, $1.10 for the grandstands, and $1.65 for box seats. A man of fabulous wealth, Marshall knew how to give the fans what they wanted.

On October 2, 1932, the Braves, adorned in blue and gold uniforms, the colors of Marshall’s Palace Laundry empire, played their inaugural game, at home, versus the Brooklyn Dodgers. The previous season, Brooklyn had finished ninth in the league, with a record of 2-12-0. Behind their new coach, future NFL Hall of Famer Benny Friedman, the Dodgers shut out the Braves, 14-0, the first of just three wins the Dodgers garnered that year. A week later, the Braves were scheduled to play the New York Giants, who promised to be even more challenging. Much to Marshall’s pleasure, though, this time his team produced a much different outcome.

October 9 was a sickly hot day in Boston. At Braves Field an estimated 10,000 fans endured the heat to watch the Braves take on the Giants. If those fans hoped for a change in their team’s fortunes, they must have been aghast when Pinckert fumbled the opening kickoff and the Giants recovered, beginning their first drive at the Boston 35-yard line.4 Shortly, though, the Giants, too, fumbled, and Jim Musick recovered, giving the ball right back to Boston. Thus began a back-and-forth first quarter during which both teams moved the ball with hard running and timely passing, only to encounter staunch defenses that brought about a flurry of punts.

As the clock wound down in the first quarter, the Braves finally found creases in the Giants’ defensive line. Beginning at their own 40-yard line, Musick, Pinckert, and Henry “Honolulu” Hughes, the Braves’ bruising fullback and kicker from Oregon State, via the Hawaiian Islands, alternately ran hard and moved the ball for a first down at the New York 26-yard line. As time expired in the quarter, with the two teams in a scoreless tie, the Braves seemed poised to capitalize on their first scoring opportunity of the afternoon.

With the teams reversing direction in the second quarter, the Braves continued their march to the end zone. Beginning the period, Musick carried twice to the Giants’ 17 yard-line. Over the next three plays, wingback Oren Pape, Pinckert, and Hughes each carried, but amassed only five more yards. Then, on a rare pass, Pape hit Pinckert, who advanced to the 6-yard line for a first down and goal to go. From there, Musick again crashed the line, fumbled, but recovered, resulting in a yard gain. Next, Pape drove forward to the 2, and finally,Musick sliced over the line for a touchdown. Hughes kicked the extra point, and the Braves led, 7-0.

The Giants quickly answered; after returning the kickoff to their own 43, New York proceeded to amass four first downs that delivered them to the Braves’ goal line. First, 5-foot-11-inch, 200-pound Giants end Glenn Campbell hauled in a pass and advanced nine yards, before he was leveled by the Braves’ diminutive Tony Siano; the Waltham (Massachusetts) High School and Fordham graduate stood just 5-feet-8-inches tall and weighed 172 pounds. Next, Boston’s own Jack Hagerty, from nearby Dorchester High School, and Georgetown University, maneuvered the Giants to the Braves’ 35-yard line. From there, John “Shipwreck” Kelly, Dale Burnett, and Elwin “Tiny” Feather, who was anything but, at 6-feet tall and 197 pounds, carried the ball to Boston’s 7-yard line.

Here, a rare substitution cost the Braves five yards. With one of his players tiring, coach Wray inserted second-string lineman Russell Peterson. In those days, such a move was a penalty, so the ball was placed at the 2. Impressively, the Braves held, as Peterson led the defensive line to stiffen, stopping Shipwreck Kelly on three successive carries which resulted in a gain of just one yard.

It was fourth down and one yard to go for the Giants.

In 1981 Morris “Red” Badgro, then 78 years old, was elected to the NFL Hall of Fame. A two-way end, in 1934 Badgro would lead the league in receptions, with 16. On this day, Badgro lined up at the 1 for the Giants, and immediately ran along the goal line. Deep in the Giants’ backfield, Jack Hagerty spotted the tall receiver, rifled a pass diagonally across the goal line, and Badgro snared it for a touchdown. However, Boston’s Oren Papeblocked Hagerty’s extra-point attempt, and the Giants trailed, 7-6. With time running out in the quarter, “Honolulu” Hughes later attempted a field goal for the Braves, but it sailed wide of the goal posts. So the Braves took their one point lead to the locker room.

Despite the powerful running of Giants’ fullback and former Army runner Chris “Red” Cagle, who three times led New York’s advance deep into Boston territory, the third quarter produced no scoring: twice the Giants fumbled, and the third time the Braves stopped them at Boston’s 5-yard line. With the score still 7-6, Braves, the fourth quarter ensued.

Again, the Giants’ ground attack proved lethal. As the Braves continually failed to advance the ball, Hughes punted them out of trouble, only to have New York drive the ball down the field. Finally, though, the Giants’ offense made a mistake. After yet another Hughes punt, the Giants started deep in their own territory. Quickly, they moved the ball to midfield. Then disaster struck. At the 50-yard line, Hagerty threw a two-yard toss to end Ray Flaherty, who four years later joined Boston and began a Hall of Fame coaching career. Immediately, Flaherty attempted to lateral the ball to Cagle, sprinting around the end, but the Braves’ Myers “Algy” Clark stepped in front of Cagle, intercepted the ball, and returned it untouched 55 yards for a score. Hughes’s point after kick was good, and the Braves led, 14-6. Shipwreck Kelly and Red Cagle continued the Giants’ attack, leading New York to five first downs, but couldn’t advance beyond Boston’s 17-yard line. On the Giants’ final drive of the day, Hughes intercepted a pass, and time expired.

The Braves had scored the franchise’s first victory.

The next season Marshall’s partners relinquished their ownership stakes, leaving him fully in charge of the team. After the exit of coach Wray, Marshall hired a Native American named William “Lone Star” Dietz as his replacement. In recognition, Marshall changed the team’s name to the Redskins and their colors to burgundy and gold. He also moved the Redskins to Fenway Park, where they played through the 1936 season. Throughout, Marshall was never able to cultivate a fan base, and attendance suffered. When the Redskins won the NFL’s Eastern Division in 1936, the championship game against the Western Division champion Packers was held at the Polo Grounds, in New York City.

In 1937 Marshall moved the Redskins to his hometown of Washington, D.C.

More than 75 years later, they were still there.

This article appeared in “Braves Field: Memorable Moments at Boston’s Lost Diamond” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and Bob Brady. To read more articles from this book, click here.

Sources

Smith, Thomas W., Showdown: JFK and the Integration of the Washington Redskins, (Boston: Beacon Press, 2011).

Boston Herald

Boston Globe

Boston Post

pro-football-reference.com

Notes

1 From 1925-28, the Bulldogs had been the Pottsville Maroons. Following the ’28 season, the Maroons were purchased by a Boston syndicate and relocated to Boston for 1929, but had folded after that lone abbreviated season, the only one in which the city had been represented since the NFL’s formation in 1920.

2 Among the 10 teams who competed in 1931, the Providence Steam Roller, Cleveland Indians, and Frankford Yellow Jackets were no longer members of the NFL. Boston’s addition restored the league to eight teams.

3 Thomas W. Smith. Showdown: JFK and the Integration of the Washington Redskins, (Boston: Beacon Press, 2011), ebook version, 12.

4 In researching this article, the author utilized multiple daily periodicals. With few exceptions, each periodical differed with respect to attendance figures, yardages and sometimes, even the identify of players. Such was the novelty of football reporting at time. Where possible, the figure most often quoted is used as the primary source.

Additional Stats

Boston Braves 14

New York Giants 6

(National Football League)

Braves Field

Boston, MA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.