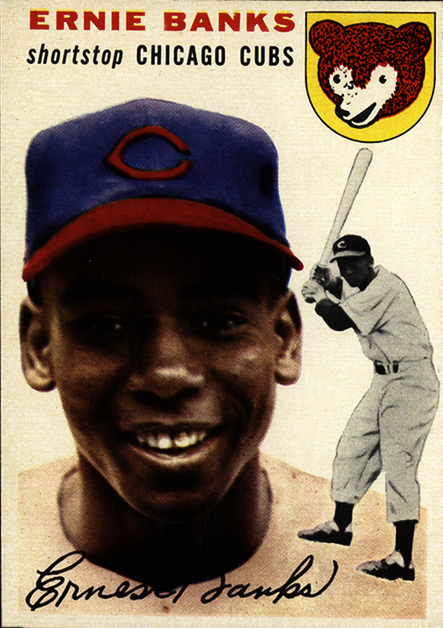

September 17, 1953: Ernie Banks breaks color barrier for Cubs

It’s not so much what Ernie Banks did on Thursday, September 17, 1953. Rather, it’s what the game meant to the Chicago Cubs’ franchise and major league baseball in general.

It’s not so much what Ernie Banks did on Thursday, September 17, 1953. Rather, it’s what the game meant to the Chicago Cubs’ franchise and major league baseball in general.

The 22-year-old Dallas, Texas, native went hitless in three at-bats, scored one run, and made an error at shortstop in his major league debut. The Cubs lost, 16-4, to the Philadelphia Phillies that day in route to a seventh-place finish in the eight-team National League. Banks’ new team finished with a 65-89 record, 40 games behind the pennant-winning Brooklyn Dodgers.

Appearing at Wrigley Field for the first time in a Cub uniform, Banks became the first African American to play for the 77-year-old Chicago franchise. Ironically, Cap Anson, the legendary Cub first baseman of the 1800s, set an early exclusionary tone by refusing to play teams with blacks.

What was Chicago like in the early 1950s when the young 6-foot, 175-pound infielder joined the Cubs after an all-star season with manager Buck O’Neil’s Kansas City Monarchs, one of the most successful teams in the Negro American League?

“Most Chicago whites hated blacks,” columnist Mike Royko said. “The only genuine difference between a Southern white and a Chicago white was in their accent.”1 Edwin Berry, the executive director of the Chicago Urban League, described Chicago as “the most residentially segregated city in the United States.”2

“Into this milieu came a black man who today is called Mr. Cub. The impact this quiet man made on a populace so firmly entrenched against blacks in general was amazing,” author Peter Golenbock said in 1999. “It is Ernie Banks’s greatest legacy, more important than all the home runs he hit.”3

So when the Cubs purchased Banks contract for $15,000 from the Monarchs on September 7, 1953, he stepped into a world he was not accustomed to. “During my half-month stay with the Cubs in September [1953], I met more white people than I’d known in all my 22 years,” Banks observed.4

But it all worked out. Banks played in 2,528 games under a dozen different managers from 1953 to 1971 to break Anson’s club record. Mr. Cub still holds club records for at-bats (9,421), total plate appearances (10,395), total bases (4,706), extra base hits (1,009), intentional walks (198), and sacrifice flies (96). He ranks second in hits (2,583), home runs (512), and RBIs (1,636).

Scouting reports by Hugh Wise and Ray Blades piqued the Cubs’ interest in Banks before the Negro Leagues’ annual East-West All-Star Game in 1953. Wise wrote, “This player has got it and I strongly recommend we negotiate for his services.”5 Blades concurred, telling personnel director Wid Matthews, “You wouldn’t believe it if I told you. Go see him for yourself.”6

So Matthews saw Banks play with the Monarchs in Des Moines and Kansas City before the East-West All-Star Game on August 16 at Chicago’s Comiskey Park. Although Banks went hitless, he handled seven chances in the field flawlessly as the West won, 5-1, before an estimated 10,000 fans.

Three weeks later, Monarchs owner Bill Baird arranged a meeting with Matthews at the Conrad Hilton Hotel in Chicago as the Monarchs’ season was ending. “Tell you what I’ll do,” Matthews told Baird. “Put a price on the two [Banks and pitcher Bill Dickey] boys. I’ll take it or leave it within five seconds and that’ll be the end of our negotiations.”7

That evening, O’Neil located Banks in the lobby of the Pershing Hotel in Chicago and told Banks: “Get hold of Bill Dickey and the two of you meet me in the lobby at seven tomorrow morning.”8

When their taxi cab arrived at its destination on the Chicago’s North Side the next morning, Banks noticed a big red sign that said “Welcome to Wrigley Field.” “What it this, Buck?” Banks asked O’Neil.9 Banks and 19-year-old Dickey followed O’Neil up to Matthews’s office where they were told Banks would report directly to the Cubs after the Monarchs’ season ended in Pittsburgh the next week. Meanwhile, Dickey would be sent to the Cubs’ Class B affiliate in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. “We like you as a player and know that you can play here at the major league level,” Matthews told Banks.10

When the $800-a-month contract was put in front of him to sign, “I had to hold my right hand with my left as I scribbled ‘Ernest Banks’ on a document that seemed to be a mile long,” Banks said.11 Despite telling sports writer Jim Enright a little later that he was pleased to become a major leaguer, Banks had reservations, though. “I was in my own comfort area and I liked being with the guys [on the Monarchs]. We cared about each other. They were like my family. I didn’t want to leave them.”12

But Monarchs second baseman Sherman Brewer set Banks straight. “You’ve got to go. It’s the major leagues,” Brewer said. “That’s as high as you can go.”13

Fittingly, Banks scored the Monarchs’ winning run in his last game in the Negro Leagues in Pittsburgh on September 13, 1953. The Monarchs defeated the Birmingham Black Barons that day, 5-2, and, 2-1, before only 1,400 fans at Forbes Field. In the nightcap Banks opened the seventh inning with a single, stole second, and scored the decisive run on Henry Bayliss’s single to left. Thereafter, Banks headed to Chicago with $10 from O’Neil to join the Cubs.14

When Banks reported to Wrigley Field on Monday, September 14, 1953, he was joined by another African American, infielder Gene Baker of Davenport, Iowa. The Cubs had bought Baker’s contract from Triple-A Los Angeles of the Pacific Coast League on September 1, making Baker the first of his race on the Cubs’ major league roster. Six years older than Banks, Baker had spent six years in the Cubs’ minor league system, including the past three years in Los Angeles. But the more gregarious Baker didn’t get into his first major league game until September 20 due to a pulled muscle in his left side.

After veteran outfielder Ralph Kiner showed Banks around, clubhouse attendant Yosh Kawano gave Banks a uniform with number 14 on it and a locker next to Hank Sauer, another veteran outfielder and the National League’s Most Valuable Player in 1952. “Ernie felt as if he were in a fog as he was shuttled from the clubhouse to the field, met numerous strangers, and shook bunches of hands,” author Wilson says.15 The strangers included announcer Jack Brickhouse, who told Banks, “You’ll do fine. Just go out and play.”16

Banks immediately displayed his unusual power, hitting the first pitch in batting practice over the left field wall. “It was surprising how far he could hit a ball being so skinny,” teammate Ransom “Randy” Jackson said.17 Another Cub rookie, Bob Talbot, observed, “You could see the talent immediately. His hands were so quick—he could wait and hit the ball out of the catcher’s mitt.”18

Three days later, manager Phil Cavarretta told his new arrival from the Negro Leagues, “You’re playing today.”19 When Banks took the field, he was joined by Dee Fondy at first base, Eddie Miksis at second, Bill Serena at third, Kiner in left, Talbot in center, Sauer in right, rookie hurler Don Elston on the mound, and Clyde McCullough behind the plate. The outcome never was in doubt after four innings when the Phillies led 8-0.

Banks flied out to center in the second, walked and scored on pinch-hitter Tommy Brown’s homer in the fifth, flied out to right in the sixth, and flied out to right in the eighth. Despite absorbing the loss, Elston went on to appear in 448 games as the Cubs’ top relief pitcher from 1957 to 1964.

Three days later, Banks hit his first major league home run off the Cardinals’ knuckleballer Gerry Staley at Sportsmen’s Park in St. Louis. He ended his first major league season with a .312 batting average, two homers, and six RBIs in 10 games and 35 at bats. Only six of the 16 major league teams at the time had integrated. Five other teams did so the next season, leaving only the Yankees, Red Sox, Tigers, and Phillies without an African American player after the 1954 season.

Banks and Baker started playing together on September 22, 1953, during a doubleheader in Cincinnati. Thus, they became the first African American keystone combination in major league history. They remained a middle infield duo until Baker was traded with Fondy to the Pittsburgh Pirates on May 1, 1957, for first baseman Dale Long and outfielder Lee Walls.

Acknowledgments

The author is indebted to Larry Lester, chair of SABR’s Negro Leagues Research Committee, for his assistance.

Sources

“KC Monarchs Down Barons In Twin Bill,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 19, 1953.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/CHN/CHN195309170.shtml

mlb.com/cubs/history/all-time-leaders

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1953/B09170CHN1953.htm

Notes

1 Doug Wilson, Let’s Play Two: The Life and Times of Ernie Banks (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2019), 44.

2 Wilson, Let’s Play Two: The Life and Times of Ernie Banks, 44.

3 Peter Golenbock, Wrigleyville: A Magical History Tour of the Chicago Cubs (New York, New York: St. Martins Press, 1999), 347.

4 Rich Cohen, The Chicago Cubs: The Story of a Curse (New York, New York: Picador, 2017), 102.

5 Ron Rapoport, Let’s Play Two: The Legend of Mr. Cub, the Life of Ernie Banks (New York, New York: Hachette Books, 2019), 78.

6 Rapoport, Let’s Play Two: The Legend of Mr. Cub, the Life of Ernie Banks, 78.

7 Rapoport, Let’s Play Two: The Legend of Mr. Cub, the Life of Ernie Banks, 81.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Rapoport, 82.

11 Ibid.

12 Rapoport, 83.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Wilson, 52.

16 Ibid.

17 Wilson, 53.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

Additional Stats

Philadelphia Phillies 16

Chicago Cubs 4

Wrigley Field

Chicago, IL

Box score + PBP

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.