September 21, 1943: Powerful Grays, upstart Black Barons take center stage at Griffith Stadium

Griffith Stadium hosted Game One of the 1943 Negro League World Series between the heavily favored Homestead Grays and the underdog Birmingham Black Barons. Game Two was played in Baltimore, followed by a return to Griffith for Game Three. Games Four through Eight would be held in Chicago; Columbus, Ohio; Indianapolis; Birmingham; and Montgomery, Alabama. Game Two ended in a tie, making Game Eight necessary.

Griffith Stadium hosted Game One of the 1943 Negro League World Series between the heavily favored Homestead Grays and the underdog Birmingham Black Barons. Game Two was played in Baltimore, followed by a return to Griffith for Game Three. Games Four through Eight would be held in Chicago; Columbus, Ohio; Indianapolis; Birmingham; and Montgomery, Alabama. Game Two ended in a tie, making Game Eight necessary.

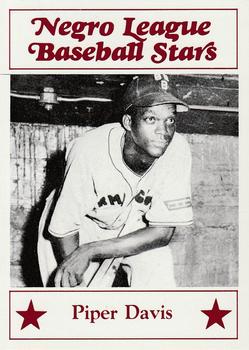

Birmingham, managed by Winfield “Gus” Welch, won the first half of the Negro American League season and finished with a 44-34 record overall. The Chicago American Giants, 34-33 for the season, won the second-half title, and the two clubs squared off in a best-of-five playoff series. The series went the limit, with Birmingham winning a Game Five thriller at their home ballpark, Rickwood Field, 1-0. John Huber (4-3, 2.81) pitched a masterful one-hitter over Chicago in the Black Barons’ 1-0 win. Huber allowed a leadoff single in the first, but that runner was thrown out attempting to steal. Huber allowed only one walk the rest of the way. The Barons were limited to four hits by Gentry Jessup, but Piper Davis was hit by a pitch and later scored on a fly ball for the lone run.1

The Homestead Grays, named for their original home of Homestead, Pennsylvania, a Pittsburgh suburb, now mostly considered Washington their home. But wherever they played, they were a Negro League powerhouse. Candy Jim Taylor’s crew went 78-23 in Negro National League competition in 1943, winning the pennant. The Grays had won four straight NNL pennants and seven of the last eight. The Grays had been swept by the Kansas City Monarchs, 4-0, in the 1942 Negro League World Series, the first such postseason series between the two league champions.

The Grays lineup featured Negro League stars aplenty, including some who would one day be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. Third baseman Jud Wilson, outfielder Cool Papa Bell, pitcher Ray Brown, first baseman Buck Leonard, and catcher Josh Gibson were greats among their peers. Gibson batted an astounding .466 with 20 home runs and 109 RBIs in 1943, and seven other starters hit .330 or better.

Birmingham, however, had no such star-studded cast and no future Hall of Famers. Their Negro American League pennant was their first. They were making a name for themselves in Negro League baseball, however, being “the toast of the country with their brilliant and hustling play,” wrote the Pittsburgh Courier.2 “This is the best team turned in by any southern city since the days of Satchel Paige, Bill Willis, Harry Salmon, and Sam Streeter,” the paper boasted, comparing them to the Birmingham club of 1928 that included the legendary Paige.

The Courier writer said of the Barons, “There are no Gibsons or Leonards, but what the Barons lack in distance blasting, they make up in superb pitching.”3 One such pitcher was Alvin Gipson, who had recently struck out 20 in a game.4 The Grays easily won an earlier matchup, 7-0, but then narrowly defeated the Barons in a later contest, 3-2, in 12 innings.5

Logistics in the Negro Leagues were always an obstacle. Cumberland Posey, one of the Grays’ owners and a person of influence in the league, described in the Courier the issues clubs faced in scheduling since they had to rent stadiums and schedule their games around those of white teams. The series itself might have been played solely in the Midwest, Posey wrote, had it not been for Clark Griffith rearranging the Senators’ schedule to accommodate the Negro League games at Griffith Stadium.6 The Senators’ season-ending 14-game homestand was compressed into four single games and five doubleheaders to create open dates for Games One and Three of the Negro League World Series. “That is something to think about,” an appreciative Posey said.7

Posey also bemoaned the last-minute scheduling. The World Series games “should receive publicity throughout the year. Tentative dates should be agreed upon when schedules are drafted.”8 Another problem was that the Negro American League had a postseason playoff series while the Negro National League pennant was already decided when the Grays won both halves. “The Grays were compelled to remain idle a whole week after the regular season closed waiting to see whom they would play in the world series.”9 Yet the game went on despite the obstacles.

Pitching for Birmingham was Alfred “Greyhound” Saylor (often spelled Sayler), a 31-year-old right-hander from Blytheville, Arkansas, who was 5-3 with a 2.52 ERA. Johnny Wright, who led all Negro League pitchers in wins (20), games (35), games started (26), complete games (17), shutouts (5), innings pitched (212), and strikeouts (118) with a 2.33 ERA, took the hill for the Grays. Wright’s numbers, like all Negro League statistics, are certainly nowhere near the accuracy we expect in the modern-day. Nevertheless, Wright’s season surpassed that of even Paige himself, the greatest of his generation.

Despite “adverse weather conditions,” a crowd of 4,000 came out to Griffith Stadium for the 8:30 P.M. start.10 Francis “Eggie” Greenfield (first base), Fred McCrary (home plate), and Ducky Kemp (second and third) were the umpires.

Felix McLaurin, a .294 hitter in 1943, led off for the Black Barons and lined a scorching double past Leonard at first and down the right-field line. Tommy Sampson followed with a single to right, sending McLaurin home. Sampson was thrown out by Josh Gibson attempting to steal. Clyde “Little Splo” Spearman doubled. Piper Davis singled, sending Spearman to third. Spearman scored on an error by Gibson. The Washington Post described the error as a bad throw to second, implying that Davis attempted to steal. The Baltimore Afro-American wrote that Gibson missed a low pitch and was sliding in the mud to get it, allowing the run to score. Both events could have happened on the same play, but in any event, the Barons now led 2-0.

The Grays countered with a run in the first. Bell led off with a triple to the left-field wall and scored on Leonard’s fly ball to center.

The Barons carried their 2-1 lead into the fourth inning when they struck again. Lester “Buck” Lockett launched a double to left over Bell’s head and scored when Leonard “Sloppy” Lindsay singled to left.

Wright survived those two unearned runs in the first and left with a 3-1 deficit after six innings. He had struck out eight, walked four, and danced around the eight hits he allowed. The veteran Ray Brown, 8-1 that season with a 3.54 ERA, took the mound in the seventh. He got into a heap of trouble immediately. Hoss Walker, the Barons’ 38-year-old third baseman, singled. Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, a 40-year-old catcher on loan to the Barons from Chicago (which resulted in controversy among sportswriters), also singled, and McLaurin was safe on shortstop Sam Bankhead’s fielding error. Walker scored on the mishap, and the Barons led 4-1.11

Besides those unearned runs in the first, Saylor did not allow another baserunner until the ninth. That was when he seemed to tire; with one out he walked Leonard and Gibson. Howard Easterling singled to score Leonard, and with the score 4-2, the potential winning run would be coming to the plate. However, Easterling tried to stretch his hit into a double and was thrown out. Bankhead, whose ninth-inning error seemed much larger now, couldn’t atone for his gaffe and flied out to end the game.

After the Series, Griffith Stadium hosted “A Cavalcade of Negro Music” featuring Billy Eckstine, an event promoted as the “Greatest array of Negro Stars ever Heard Here.” Baseball fans had already seen Negro stars at Griffith Stadium, who thrilled fans with a hard-fought World Series.

Sources

Besides the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted the following:

“At Home Plate Before the Battle,” Baltimore Afro-American, October 2, 1943: 18.

“Barons Jar Grays, 4-2, in Big Series Opener,” Washington Evening Star, September 22, 1943: 18.

“Barons Turn Back Grays, 4-2, as 4,000 See Series Opener,” Washington Post, September 22, 1943: 20.

“Grays and Barons Open Negro World Series Tonight,” Washington Post, September 21, 1943: 19.

Hauser, Christopher. The Negro Leagues Chronology: Events in Organized Black Baseball, 1920-1948 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2008), 134.

Hubler, David E., and Joshua H. Drazen. The Nats and the Grays: How Baseball in the Nation’s Capital Survived WWII and Changed the Game Forever (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015), 130-131.

“Saylor Allows 5 Hits as Barons Win Series Opener,” Afro-American, October 2, 1943: 18.

Seamheads Negro Leagues Database. https://seamheads.com/NegroLgs/index.php.

Notes

1 “Birmingham Nine Wins Negro Baseball Title,” Baltimore Sun, September 20, 1943: 16; “Birmingham Team Takes Negro Title,” Huntsville (Alabama) Times, September 20, 1943: 6.

2 “Fighting Black Barons Primed for Battles with Eastern Foes,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 4, 1943: 19.

3 Ibid.

4 “Grays Primed for Series with Birmingham Barons,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 4, 1943: 19.

5 “Grays Blank Barons, 7-0,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 8, 1943: 15; “Grays, Barons Start Negro World Series Tilt Tonight,” Washington Evening Star, September 21, 1943: 22.

6 Cum Posey, “Posey’s Points,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 2, 1943: 16.

7 Cum Posey, “Posey’s Points,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 18, 1943: 17.

8 “Posey’s Points,” October 2, 1943.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 One such complaint was lodged by Art Carter (“Use of Ineligible Men Belittles World Series”) of the Baltimore Afro-American, who called the Series a “barnstorming travesty” with “Double Duty” not the only example of inconsistent enforcement of league rules. Carter complained of the “unorganized manner” in which the leagues conducted the series, validating the beliefs of many that the Negro Leagues needed a commissioner. It certainly didn’t help when the much-hyped final game of the Series was to be held in New Orleans but had to be moved. Wendell Smith of the Pittsburgh Courier blasted, “The entire promotion of the World Series was a farce.” Baltimore African American, October 9, 1943: 18; “Smitty’s Sports Spurts,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 16, 1943: 16.

Additional Stats

Birmingham Black Barons 4

Homestead Grays 2

Game 1, Negro League WS

Griffith Stadium

Washington, DC

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.