September 28-30, 1891: The Clouded Finish: Beaneaters take over first place

When first-place Chicago hosted second-place Boston on September 4, 1891, the Colts’ lead over the Beaneaters was six games. Colts manager Cap Anson was so confident of winning the pennant that he entertained the crowd by wearing a white flowing beard throughout the game. The Colts’ 5–3 victory increased the lead to seven games.

Ten days later it was down to 4½ games as the Colts prepared to face the Beaneaters in a final three-game series between the contenders. Chicago won the first two games, raising the lead back to 6½ games. A reporter at the Chicago Daily Tribune told his readers, “The good captain’s men are champions and no mistake.”1

Ten days later it was down to 4½ games as the Colts prepared to face the Beaneaters in a final three-game series between the contenders. Chicago won the first two games, raising the lead back to 6½ games. A reporter at the Chicago Daily Tribune told his readers, “The good captain’s men are champions and no mistake.”1

Moreover, the scheduled pitchers in the third game indicated another likely win for Chicago. For Frank Selee’s Beaneaters it was Charles “Kid” Nichols, 0–9 lifetime against Chicago; and for Anson’s Colts it was Bill Hutchinson, already with eight wins against Boston this season.

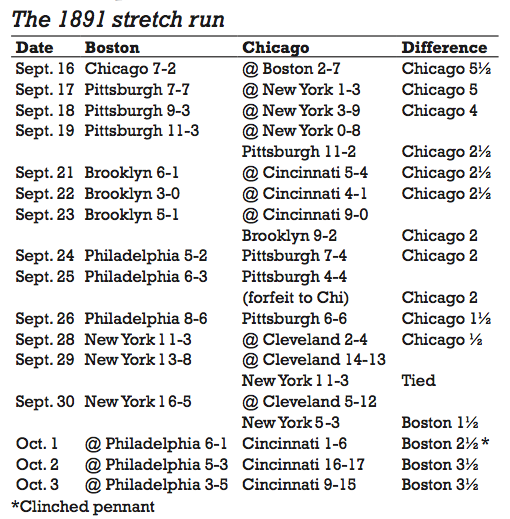

But strong pitching by Nichols, together with seven Colts errors led to a Beaneaters victory. Following a tie, the challengers embarked on a 17-game winning streak that would not end until the final day of the season. Boston’s 16th consecutive victory, on October 1 against Philadelphia, clinched the pennant.

Fifteen of Boston’s 18 wins were against Philadelphia, Brooklyn, and New York, the league’s other Eastern teams. Boston’s spectacular late-season success against its regional neighbors led to a serious post-season accusation by Chicago president James Hart. Hart charged that the Eastern teams had conspired to ensure that Boston, not Chicago, won the pennant. He alleged that players in the National League as a whole did not want the Colts, a team with the league’s lowest payroll, to be its champion.

Additionally, Hart believed that resentment against Anson still existed for his opposition to the Brotherhood-inspired Players League, many of whose former members were back playing in the National League. Adding to the mix was the animosity Giants manager Jim Mutrie harbored toward Anson over his refusal to play a postponed contest on an open date of the Giants’ choice.

Hart pointed to several instances during the streak where suspect fielding plays contributed to Boston victories. He focused mainly on the Beaneaters’ five games against the Giants on September 28–30. The series took place at Boston’s South End Grounds and included back-to-back doubleheaders. The Beaneaters, of course, won all five games, the first four by huge margins: 11–3, 13–8, 11–3, 16–5, and 5–3.

Hart pointed out the Giants had arrived in Boston for this very crucial series without their two best pitchers, Amos Rusie and John Ewing. Also absent were first baseman Roger Connor and second baseman Danny Richardson. And, Hart added, those Giants who played did so in such a casual manner that Sporting Life’s comment that “the New York’s beat all records for indifferent and rocky playing,” was typical of the reaction by the press.

The New York papers were normally fully supportive of the Giants, yet they too wrote of their suspicions. For one, they wondered why Rusie and Ewing were used against Chicago, but not against Boston. Under a headline in the September 30 New York Evening Telegram that read, “Are The Giants Trying to Defeat Anson?” the Telegram writer claimed that “Anson’s opponents are doing all in their power to prevent him from winning, but it is doubtful if New York is trying to win. This is unfortunate for it will probably leave a stigma on the National game.”2

The Giants’ lackadaisical play was so obvious that even the Boston fans booed their performance, and led Anson himself to accuse the Giants of deliberately losing the games. Rumors flew that Boston gamblers had even refused to set odds on the Beaneaters-Giants contests.

The whole controversy might have been rendered moot if Chicago had played better down the stretch. Keep in mind that the Colts had left Boston still in possession of a 5½-game lead over the Beaneaters. But they promptly lost three games in New York before finishing up just 6–5–1 in 12 games against Cincinnati, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh. Until that point, the Colts had been a combined 36–11 against the three teams.

On November 11 the league held a hearing at the Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York to consider Hart’s charges. Hart offered two more alleged items of testimony in addition to the previous evidence presented. He claimed that 10 days before the Boston-New York series, umpire Jack McQuaid had told the Chicago players that the Beaneaters would sweep the series. And, Hart added, several Cincinnati players had told certain Colts players that the Giants openly stated they would do whatever was necessary to see that Boston won the pennant.3

Despite the seemingly overwhelming evidence to the contrary, owners Arthur Soden of Boston and John Day of New York denied any wrongdoing, and the league dismissed all charges.4 However, to this day both Boston’s 17-game winning streak and its 1891 championship remain clouded with suspicion.5

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Notes

1. Chicago Daily Tribune, September 16, 1891.

2. New York Evening Telegram, September 30, 1891.

3. Chicago Daily Tribune, November 12, 1891.

4. Day was allowed to be present at the entire meeting, while Hart was allowed in only to testify.

5. For a full discussion of Boston’s winning streak and the controversy it engendered, see Robert L. Tiemann’s “The Forgotten Winning Streak of 1891” in the 1989 Baseball Research Journal, pp. 2-5.

Additional Stats

Boston Beaneaters

vs. New York Giants

South End Grounds

Boston, MA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.