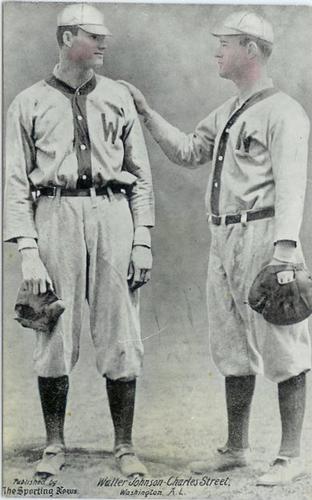

September 5, 1913: Walter Johnson spins a shutout for 30th win of season

“To encounter Walter Johnson even one time during a series is considered misfortune for any ball club,” lamented the New York Times, “but to inflict him on an opposing ball club twice in the same afternoon verges on downright cruelty.”1 The Big Train, the Washington Senators’ hard-throwing right-hander, proved to be the hero of the team’s doubleheader sweep of the New York Yankees, extinguishing a fire in the ninth inning of the first game and then tossing a shutout for his 30th victory of the season in the second contest.

“To encounter Walter Johnson even one time during a series is considered misfortune for any ball club,” lamented the New York Times, “but to inflict him on an opposing ball club twice in the same afternoon verges on downright cruelty.”1 The Big Train, the Washington Senators’ hard-throwing right-hander, proved to be the hero of the team’s doubleheader sweep of the New York Yankees, extinguishing a fire in the ninth inning of the first game and then tossing a shutout for his 30th victory of the season in the second contest.

The Senators owner-manager Clark Griffith needed a more than miracle for his third-place club (70-56) to have a chance to catch the Philadelphia Athletics, whom Washington trailed by 13 games with a month to play in the season. The Nationals, as sportswriters often called them, had been plodding along since July 31 and had lost 16 of their last 31 games, including the first game of a five-game set against the last-place Yankees (44-80) to kick off a 20-game homestand.

If the Senators had any chance for the AL flag, they’d need Walter Johnson to lead them. The 25-year-old side-armer laid claim the previous season as the best twirler in the sport, winning 33 games (one behind Smoky Joe Wood of the Boston Red Sox) and leading the majors with a 1.39 ERA and 303 strikeouts, the second time in three seasons that he surpassed the 300 mark. In 1913 the “Big Scythe,” as the Washington Times called him, was on a rampage.2 He began the day with a 29-7 slate, which pushed his career record to 144-97, and he had something to prove. In his last start, four days earlier at Shibe Park in the City of Brotherly Love, he uncharacteristically struggled, yielding a season-high six runs in a complete-game, walk-off loss in the 10th, his second consecutive defeat after 14 straight winning decisions.

On an unseasonably warm Friday afternoon, with temperatures in the mid- to upper 80s, an estimated 4,500 spectators had gathered for an afternoon of the national pastime at National Park, the Senators’ two-year-old steel-and concrete playing field. (It was renamed Griffith Stadium in 1920.) Scheduled to start the second game of the twin bill, Johnson was required to make an emergency appearance in the opener. Senators starter Joe Boehling cruised through eight innings and began the ninth with a 3-0 lead, then fell apart, surrendering two runs and loading the bases with no outs. In came Johnson, who defused the situation on four pitches. Pinch-hitter Ray Caldwell hit a fly to deep left field, which Joe Gedeon caught, then hurled a “remarkable throw,” gushed sportswriter J. Ed. Grillo of the Evening Star, to catcher Eddie Ainsmith, who tagged out the sliding Frank Gilhooley for a crushing twin killing. Johnson fanned Fritz Maisel on three pitches to end the game.

Sufficiently warmed up after his first-game heroics, Johnson took the mound in the second game in search of his 30th victory. “Unlike most managers in the Ban Johnson circuit,” suggested the Washington Herald, “[Yankees] skipper Frank Chance refused to put in a dub pitcher against the Nationals with Walter Johnson on the job and ordered Russell Ford to go to work.”3 The 30-year-old right-handed spitballer burst on the scene in 1910, winning 26 games as a rookie; so far in 1913, he sported a 12-13 slate and a 73-51 lifetime record.

“The Chancemen simply walked to the plate,” gushed sportswriter William Peet of the Washington Herald, “sniffed at Walter’s smoke, and trekked back to the bench.”4 The Big Train was dominant, as he had been in almost every game that season. He faced just 29 batters, yielding three hits and a walk, and only one batter reached second. In the first he issued a free pass to Harry Wolter, who was caught stealing; three innings later Wolter reached on a single and was gunned down again by Ainsmith attempting to swipe second. The two other hits were by, of all batters, the pitcher. Ford, who collected 32 hits in ’12, led off the third with a single and swiped second, and singled again in the ninth. Johnson fanned eight, including Birdie Cree three times, and was never in trouble. Newspapers also praised the Senators fielders. “The Nationals gave a splendid demonstration of their defensive strengths,” opined J. Ed. Grillo of the Evening Star,5 while the Times added that “senatorial speed marveled during the game.”6

Despite Johnson’s dominance and his fielders’ brilliance, the game unfolded as an unlikely pitching duel. An average offensive team, finishing fifth in the league in runs scored, averaging 3.8 runs per game, the Senators were perplexed by Ford’s wet ones. Through eight frames, the Senators had a man in scoring position only twice. In the second Frank LaPorte singled over short and stole second, but Ford punched out Ainsmith and George McBride. Johnson singled with one out in the sixth and moved to third on a groundout and passed ball, but was left stranded when Clyde Milan grounded out. Ainsmith led off the eighth with a single, but was caught stealing.

The Yankees “never had a chance” against Johnson, the New York Times sadly recounted.7 Nonetheless Ford was in “fine fettle,” noted the Washington Times, yielding only five hits and walking one through eight innings;8 while the Herald suggested that the game “would have gone into extra innings” or would have been “terminated by darkness” if not for an inopportune defensive miscue by the visitors that gave the Senators the victory.9

Ford dispatched the Big Train on a popup to third to begin the ninth. Danny Moeller followed with a single, which newspapers in the nation’s capital and New York considered only the Nationals’ second hard-hit ball of the game. After Moeller swiped second, Milan hit a routine grounder to second baseman Roy Hartzell. The eight-year veteran fumbled the ball (no error was charged) and Moeller reached third. Eddie Foster followed with what would have been the final out of the game, a fly to left fielder Cree. Moeller scored easily to tally the only run of the game and give the Senators a dramatic 1-0 victory in 1 hour and 45 minutes.

The Big Train’s 30th victory was also his 10th shutout of the season and commenced an awe-inspiring stretch to end what was surely his best season and one of the best by any hurler in baseball history. Including both games on September 5, Johnson closed out the season by winning seven straight decisions and posting a 0.62 ERA in 57⅔ innings before an ill-fated relief outing in the season’s last game. He captured the Triple Crown of pitching, leading the majors with 36 wins, a 1.14 ERA, and 243 strikeouts. He also led the big leagues with 29 complete games, 11 shutouts, and 346 innings pitched.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, SABR.org, and The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record.

Notes

1 “Johnson Saves One Game, Wins Another,” New York Times, September 5, 1913: 8.

2 “Johnson Is Star of Close Battle,” Washington Times, September 6, 1913: 14.

3 William Peet, “Nationals Won Both Ends of Double Bill from Yankees,” Washington Herald, September 6, 1913: 10.

4 Peet.

5 J. Ed. Grillo, “Johnson Saves Boehling’s Game, Then Wins His Own,” Evening Star (Washington), September 6, 1913: 6.

6 “Johnson Save One Game, Wins Another.”

7 “Johnson Save One Game, Wins Another.”

8 “Johnson Is Star of Close Battle.”

9 Peet.

Additional Stats

Washington Senators 1

New York Yankees 0

Griffith Stadium

Washington, DC

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.