1857 Winter Meetings: The First Baseball Convention

This article was written by Richard Hershberger

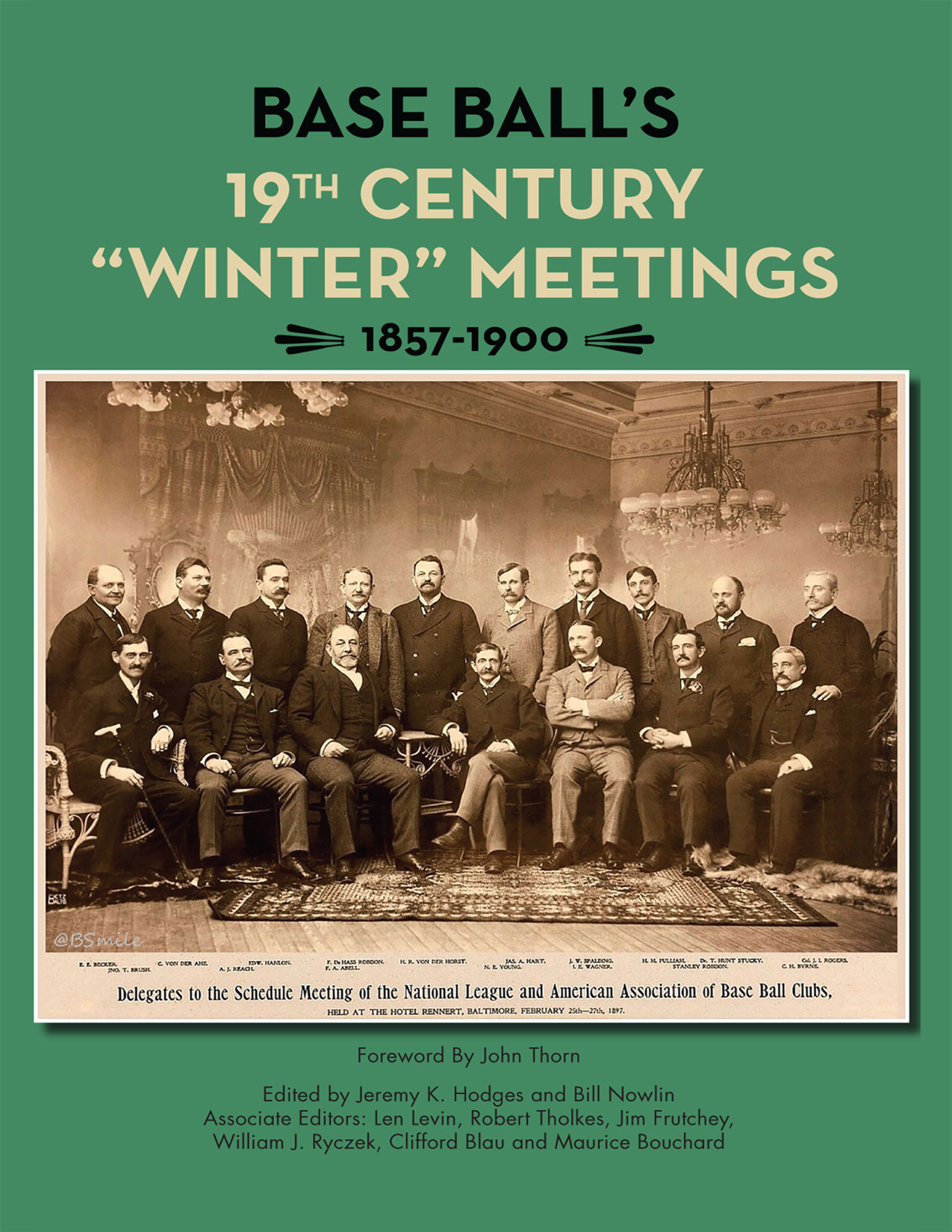

This article was published in Baseball’s 19th Century Winter Meetings: 1857-1900

Early 1857 saw the first baseball convention, beginning a series that continues, in one form or another, to the winter meetings of today. What provoked it? Why did anyone bother to initiate such a gathering? The convention was called to fill a need. It was successful enough to merit a repeat the following year, while not as successful as to eliminate the need to reconvene. The task here is to identify the problems leading to the convention, the solutions it devised, and the loose ends resulting in subsequent annual meetings.

Early 1857 saw the first baseball convention, beginning a series that continues, in one form or another, to the winter meetings of today. What provoked it? Why did anyone bother to initiate such a gathering? The convention was called to fill a need. It was successful enough to merit a repeat the following year, while not as successful as to eliminate the need to reconvene. The task here is to identify the problems leading to the convention, the solutions it devised, and the loose ends resulting in subsequent annual meetings.

Baseball in 1856 was in the midst of rapid growth.1 The Knickerbockers, the senior baseball club, had been founded in 1845, but had inspired few imitators in the early years. As late as 1854 there were only a half-dozen clubs, in New York City and Brooklyn. Then 1855 was the breakout year, with about two dozen clubs. These doubled every year up to the outbreak of the Civil War.2 This growth changed the nature of how the game was played. The purpose of a club like the Knickerbockers was to provide a vehicle for young men in sedentary occupations to take their exercise together in a socially congenial setting. They met, usually twice a week during the season, to play a game among themselves. Two captains would be appointed, and they would divide up the members present into the two sides for the day.

A club could exist indefinitely with no competition with other clubs, since outside competition wasn’t the point. But boys will be boys. Where two clubs existed in proximity, they would inevitably seek to test their mettle against each other. The two clubs would each select their nine best players for a “match game.” Initially these were also grand social events, with one club the host and the other the guest, the host making grand displays of hospitality. This would, of course, be reciprocated, with the clubs reversing their roles for the return game.

The growth spurt beginning in 1855 changed the nature of the sport. The competitive aspects soon overtook the social. An early concession to competition was the addition of a third game, often on neutral ground, should the first two games be split.3 The more insidious effect was that clubs began looking for any edge. Even apart from this, the membership of the early clubs was small. Everyone knew everyone else, and oral traditions and social norms sufficed to fill in the gaps in the formal rules. As the game expanded this became less true, so the formal rules had to be expanded in response. Finally, the players got better with practice. Rules well adapted for poor players often prove unbalanced with adept players.

The early rules provided ample opportunity both for gamesmanship and confusion. The Knickerbockers’ rules had been drafted in 1845 for intramural play. They were slightly revised in 1848, and in 1854 the Knickerbockers had met with two other clubs, the Gothams and the Eagles, to draft another revision for match games. The 1854 meeting was necessary because the three clubs had slightly different rules, which needed to be reconciled. The competitive stew of 1855 made apparent the need for revisions. An attempt was made after the 1855 season to convene a convention to address the problem, but little seemed to come of it. A possible explanation was the conspicuous absence of the Knickerbockers.4 This changed a year later.

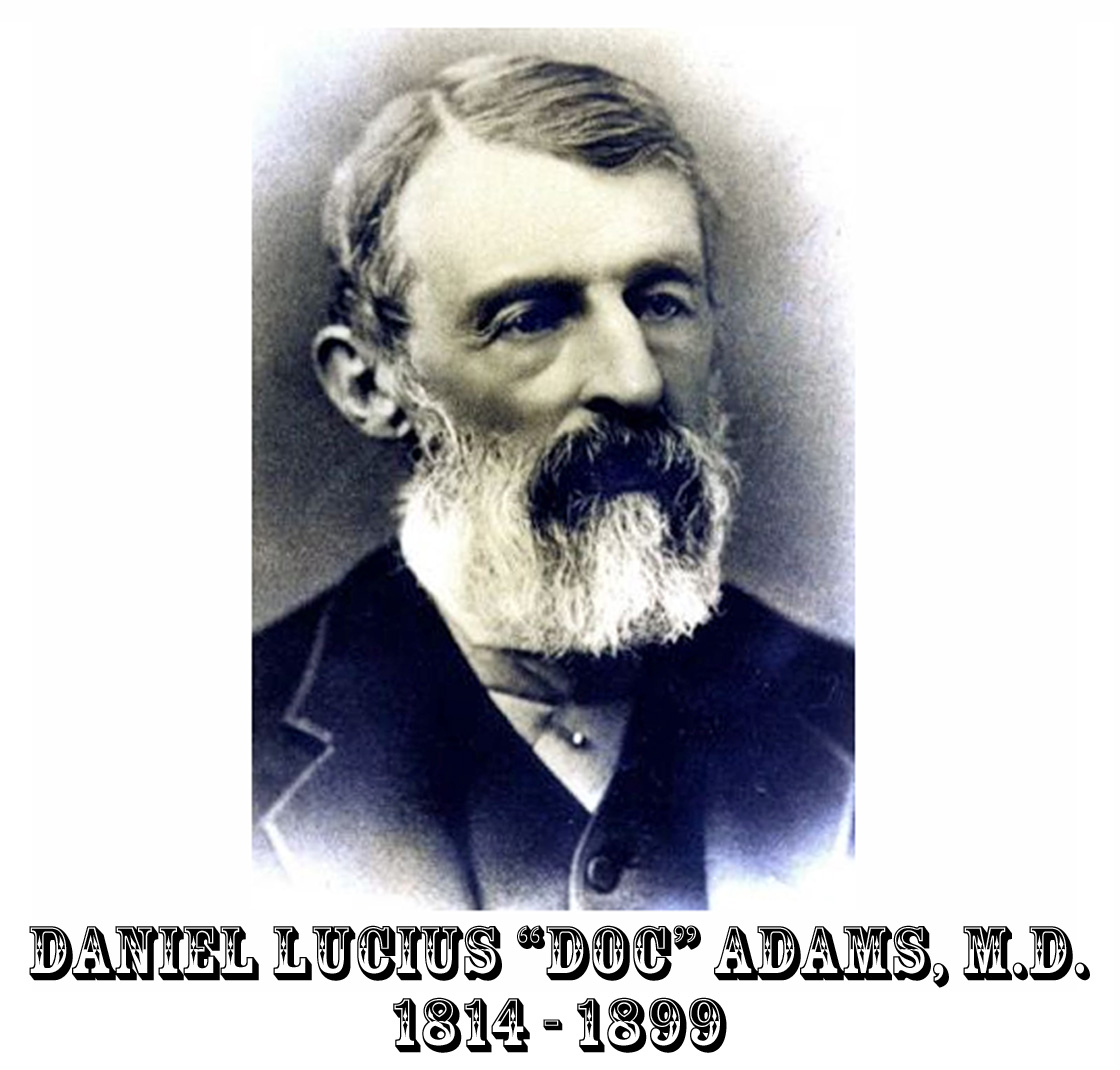

The reasons for the club’s change of heart are not recorded, but we can infer that the situation was increasingly untenable. In December of 1856, the clubs issued a call for a convention to be held the following January, and the 1857 convention met in two sessions, on January 22 and February 25. The first session appointed a rules committee, which met on January 28. Fourteen clubs sent three delegates each to the first session. Two additional clubs sent delegates to the second session. Some clubs’ delegations from the first session did not return, so the full 16 clubs never actually met together. The first order of business was for the convention to organize itself with the election of officers. The senior status of the Knickerbocker Club was recognized when its president, Daniel “Doc” Adams, was elected president of the convention. Other clubs were then recognized through the election of a superfluity of officers: two vice presidents, two secretaries, and a treasurer, each from a different club.5

The reasons for the club’s change of heart are not recorded, but we can infer that the situation was increasingly untenable. In December of 1856, the clubs issued a call for a convention to be held the following January, and the 1857 convention met in two sessions, on January 22 and February 25. The first session appointed a rules committee, which met on January 28. Fourteen clubs sent three delegates each to the first session. Two additional clubs sent delegates to the second session. Some clubs’ delegations from the first session did not return, so the full 16 clubs never actually met together. The first order of business was for the convention to organize itself with the election of officers. The senior status of the Knickerbocker Club was recognized when its president, Daniel “Doc” Adams, was elected president of the convention. Other clubs were then recognized through the election of a superfluity of officers: two vice presidents, two secretaries, and a treasurer, each from a different club.5

The next item was the revision of the rules. The Knickerbockers had prepared a draft set, which they proposed to the convention. Any hope of pushing it through quickly and intact was soon dashed. The convention decided instead to form a committee to consider the proposals. This led in turn to a discussion of how to constitute the committee, with suggestions running from the convention appointing five members, to the convention meeting as a committee of the whole. They finally settled on each club choosing one delegate. This was the committee that met six days later.

The purpose of the convention was next expanded by a discussion of the desirability of a baseball ground in the new Central Park, and a committee of five was appointed to lobby the Central Park commission. (They were unsuccessful in the short term, but parts of the park were opened to junior clubs several years later.) Three balls of varying size and weight were presented, an assessment of $2 per club was voted to defray the expenses of the meeting, and the meeting adjourned.

The rules committee met six days later. The committee elected William H. Van Cott of the Gotham Club chairman, and considered the draft rules presented by the Knickerbockers. Some proposals survived intact, some were amended, and some nixed entirely. The committee prepared a final draft and presented it to the second session of the convention, which made some additional amendments proposed from the floor and finally adopted the rules of 1857.

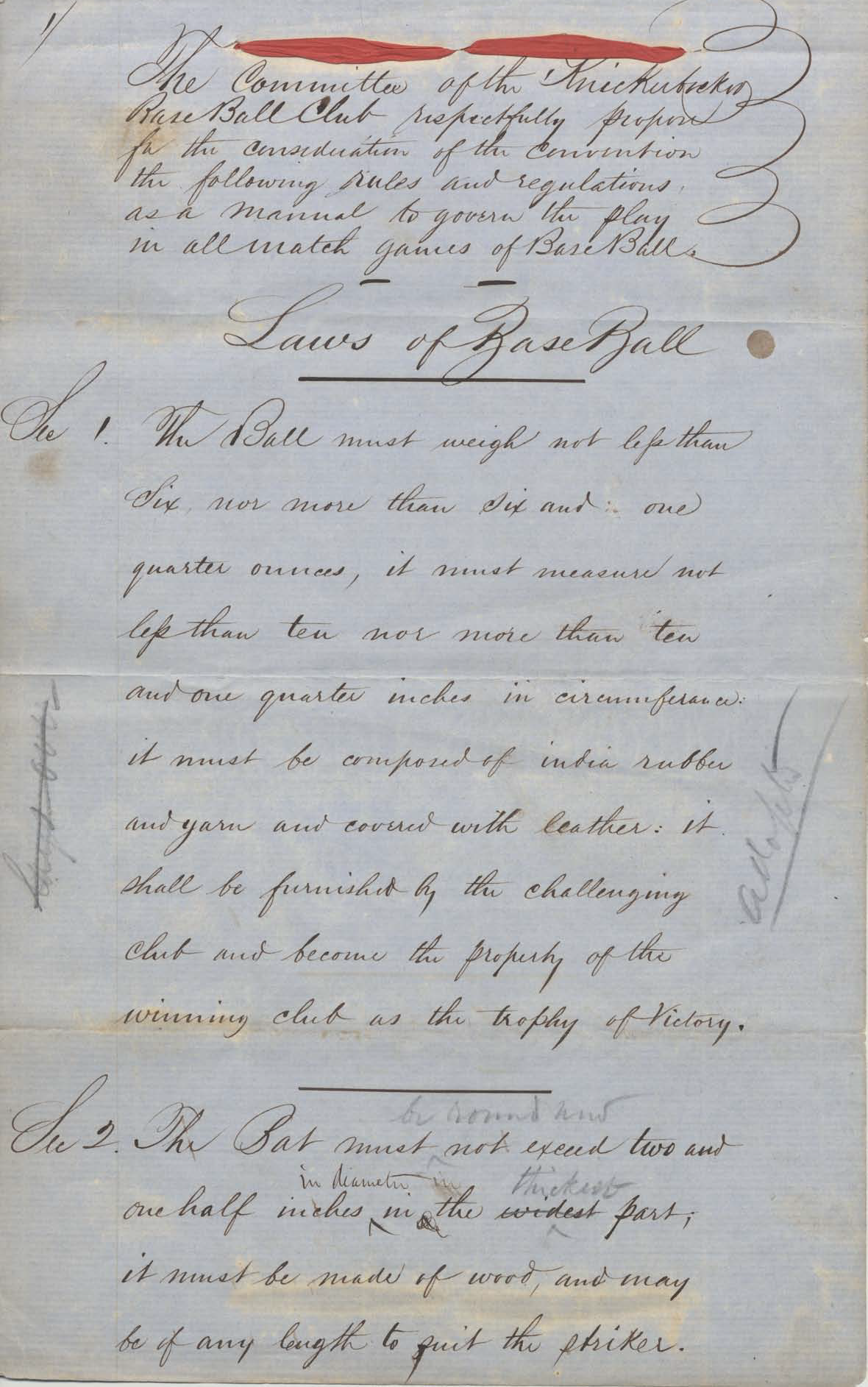

Laws of Baseball, KBBC to Convention, January 22, 1857, page 1 (COURTESY OF JOHN THORN)

Some of the new rules were really clarification of existing practice. The bat was defined to be round. (The Knickerbockers proposed allowing one side to be flat, copying the cricket bat, but this idea did not make it out of the rules committee.) The dimensions of the diamond were more precisely defined. The previous rules had used the “pace” as the unit of measurement, but did not define its length. Plausible modern suggestions include 2½ feet, 3 feet, or the stride of a person actually pacing out the diamond. The new rule replaced the pace with the yard, removing the ambiguity. The pitcher was required to deliver the ball at least 15 yards from the batter, where previously no distance had been specified. The existing rules had included the balk, but had not defined what one was. The 1857 rules, however, stated, “Whenever the pitcher draws back his hand with the apparent purpose or pretension to deliver the ball, he shall so deliver it,” with a balk the penalty for failure to deliver the ball.

The 1857 rules specified that an uncaught foul ball was dead, and that it was live when returned to the hands of the pitcher. The placement of the batter was specified, and the requirement that runners run directly to the base, which hints at previous extreme attempts at evading a tag. One particularly interesting clarification was setting a team at nine players. This often receives a lot of attention today, but it wasn’t actually new. Nine on a side had been the standard for match games throughout the 1850s. Intramural club games varied wildly, but match games were standardized, in fact, long before this was put into the rules. The new rules also provided for two umpires and a referee. This too had been standard practice, with each club appointing an umpire. Should they be unable to resolve any dispute between themselves, they would refer the matter to the referee. (The umpires took on the role of advocates rather than arbiters, which role proved superfluous at best. The system was soon abandoned in favor of a single, theoretically impartial umpire.6)

The ball was standardized at 6 to 6½ ounces and 10 to 10¼ inches in circumference. This is noticeably larger than the modern ball. Curiously, the 1854 rules had set the ball at very close to the modern size. It would be gradually shrunk back to its modern size over the course of the 1860s.

The most truly innovative new rule — and arguably the centerpiece of the convention — was the change in how the game ended. The old system had the game over at the end of the inning once one side had 21 runs. (Scoring was generally higher in that era, and 21 runs was not an absurd number.) The convention adopted the modern rule of ending the game after nine innings. Why make this change? The key is that it also adopted the modern rule that the game was official after five innings, even if called for darkness or rain. (These are not exactly like the modern rule. The inning had to be completed, even if the side batting second had the higher score.)

This was quite brilliant, but for a reason that is obscure to the modern American: the distinction between a “tie” and a “draw.” These terms mean the same thing today, but did not at the time (and still don’t in British English). To understand the distinction, we must turn to cricket. A cricket match, in its full traditional form of international test match competition, lasts two innings over five days. If at the end of these two innings the two sides have the same score, the result is a tie. This is very rare. If, at the end of the five days allotted to the match, the two innings have not been completed, then the result is a draw. In either case the effect is that neither side won or lost.

The implication is that, should one side over the course of the match come to the unhappy conclusion that it isn’t going to win, it can stall out the remainder of the game in its turn at bat. This is a legitimate strategy in cricket, and works due to the nature of the game. The stalling side bats extremely conservatively, batting not to score runs but merely to avoid getting out. Consider that the batsman is not required to run on groundballs, and the possibility of stalling indefinitely becomes clear. But the defending side still has the ability to put batsmen out: The batsman might make a mistake and hit the ball in the air, or he might miss the ball entirely and have his wicket knocked down. Even while stalling, the game is still being played.

The early baseball players adopted the concept of the drawn game from cricket. It seems to have been assumed, without any mention in the rules one way or the other. The problem was that baseball, as it existed in 1856, allowed the batting side to stall by simply refusing to swing at pitches. There was not yet a called strike, so there was no mechanism to force the batter to make a good-faith effort. The fielding side could also stall, by refusing to put the batter or runners out. This would run up the score, but the whole point of stalling was that the one side knew they weren’t going to win anyway.

Worst of all, these strategies were boring for everyone, players and spectators alike. This was a major — even existential — problem. A list published in late 1856 of 55 games played the previous season shows nearly one in five ended in a draw.7 Something had to be done.

The answer to this problem, adopted at the 1857 convention, was the nine-inning game, with the game official after five innings. The idea was that a team was unlikely to despair of victory and go into stall mode before the game was half over. The five-inning portion of the rule was not the afterthought it might appear, but in fact a critical feature.

Changing the game to nine innings was largely successful, as seen in the 1857 season. There were still situations where a team might have an incentive to stall. Suppose it batted first, and led after eight innings. Should the opposing side take the lead in the bottom of the ninth inning, the fielding side might suddenly find itself uninterested in getting the final out before the game was called on account of darkness, and the score reverted to the last complete inning. Such circumstances were far less frequent, however. More common was the batting strategy of the “wait game,” where once a runner was on base, the batter would refuse to swing at any pitch, since eventually one would get past the catcher, allowing the runner to advance. The solution to this would come later in the form of strikes. In the meantime, the rule successfully converted the problem of stalling from an existential threat to the game to a marginal issue.

There are still two questions about the nine-innings rule: why nine, and why innings at all? The game could have been kept at 21 runs with the victory given to the side with the most runs, should play be ended prematurely. The switch to innings seems to have been to more nearly standardize the time of play. The time spent per inning was more constant than the time spent per run, so a standard number of innings would result in a roughly predictable game length. The reason why nine was chosen is more of a mystery. The Knickerbockers’ draft rules set it at seven, and this is what came out of the rules committee. The change to nine was one of the amendments from the floor of the second general session. To add to the mystery, the amendment was proposed by Louis Wadsworth, one of the Knickerbockers’ delegates. This seems to have been an internal club dispute made public, but the arguments for the two sides are not recorded.8

Finally, the convention enacted a set of what might be called administrative rules governing player eligibility and taking a first stab at controlling gambling. Clubs were already starting to bring in ringers for important matches. The new rules required that all players be members of the club, and prohibiting any player from holding membership in more than one club, as well as anyone involved in the match from betting on the game. The code ended with a rather unrealistic rule that a side would forfeit the match if more than 15 minutes late to the ground, which proved unrealistic in the face of the umpires’ unwillingness to enforce such a draconian measure.

In addition to the rules enacted, there was one important rule that was not: the fly game. The old rules gave an out to a fielder catching a batted ball either on the fly or on the first bounce. This was known as the “bound game.” The Knickerbockers’ draft rules proposed changing this to giving an out only for a batted ball caught on the fly: the “fly game.”9

The fly-game proposal was hugely controversial. On the one hand, most clubs opposed the idea. They were happy with the bound rule and saw no reason to change it. On the other hand, some of the most prestigious clubs were included in the minority favoring the fly game. The idea was to make fielding more difficult, and therefore manlier, and thus the game more suitable for adults.

The proposal could not be dismissed out of hand, but neither was the rules committee willing to endorse it. It instead attempted to strike a compromise. It retained the bound out, but made a fly out more valuable. The previous game allowed baserunners to advance freely on any fair ball. That is, a fly ball that was caught was treated the same as a groundball into the outfield. Baserunners could move up without having to first tag up. The compromise the committee devised was to leave this rule intact for bound catches while prohibiting the runners from advancing at all on fly catches. A ball caught on the fly, whether fair or foul, was defined as being a dead ball, just as was an uncaught foul ball. This rule would two years later evolve into the modern rule of the runner returning to his base and tagging up. In the meantime, its intent was to give fielders an incentive for the more difficult fly catch.

The convention of 1857 was a watershed moment in baseball history. Later observers would often identify it as the origin of modern, organized baseball. This depends on how we define our terms; baseball history does not always allow for origin stories that are both simple and accurate. But 1857 is as good a candidate as any.

Notes

1 The word “baseball” is used here to refer exclusively to the New York game, from which modern baseball descends. There were many other forms of baseball played at the time, but they are beyond the scope of this discussion.

2 Richard Hershberger, “The Antebellum Growth and Spread of the New York Game,” Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game, v.8 (2014).

3 New York Herald, September 14, 1855; September 22, 1855.

4 New York Daily Tribune, December 10, 1855.

5 There are multiple newspaper accounts of the proceedings. The most useful are Porter’s Spirit of the Times, January 31, February 28, March 7, 1857; New York Herald, January 23, March 2, 1857; New York Evening Express, January 23 and 31, 1857.

6 Porter’s Spirit of the Times, January 2, 1858.

7 Porter’s Spirit of the Times, December 27, 1856.

8 The Porter’s and Herald accounts (probably written by the same person) state that Wadsworth was also the Knickerbockers’ delegate in the rules committee. This is most likely not true, and it was William Grenelle. The Express account names him, and records a self-deprecating speech from the committee meeting. The record of Wadsworth does not suggest that self-deprecation was among his personality traits.

9 This discussion was only with regard to fair balls. Foul balls caught on the bound were still outs under the Knickerbockers’ proposal. That discussion would come two decades later.