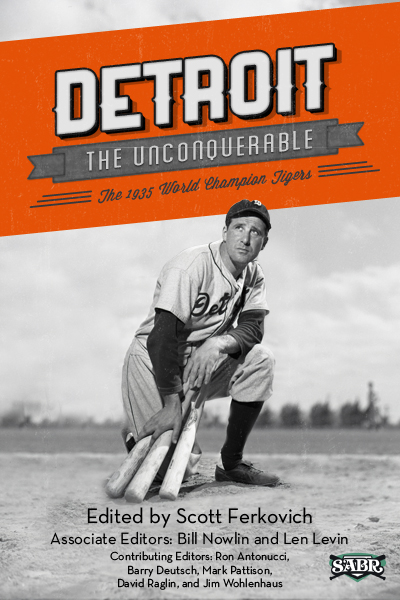

1935 Detroit Tigers: City of Champions

This article was written by Rob Hilliard - Larry Hilliard

This article was published in 1935 Detroit Tigers essays

In 1935 the City of Detroit forged a bond to its sporting teams that is an integral part of the psychology of the city, even today. In 1935 the City of Detroit forged a bond to its sporting teams that is an integral part of the psychology of the city, even today. What makes Detroit a great sports town? The stability of today’s sports franchises can be totally traced to the magical year when the baseball, football, and hockey teams all won championships in their professional sports leagues and Detroit was home to the greatest boxer of his time. It was the combined success of Detroit’s sportsmen. The single most uniting force among the diverse population was the pride that the citizens felt in its sports heroes.

In 1935 the City of Detroit forged a bond to its sporting teams that is an integral part of the psychology of the city, even today. What makes Detroit a great sports town? The stability of today’s sports franchises can be totally traced to the magical year when the baseball, football, and hockey teams all won championships in their professional sports leagues and Detroit was home to the greatest boxer of his time. It was the combined success of Detroit’s sportsmen. The single most uniting force among the diverse population was the pride that the citizens felt in its sports heroes.

The Tigers had been around since the turn of the 20th century and had been playing baseball in the same location at Michigan Avenue and Trumbull Street for more than 30 years. It was really the Tigers’ World Series championship, along with the rise of boxer Joe Louis, which was at the center of the claim as City of Champions. The Tigers had Hank Greenberg, who was a source of pride for Detroit’s Jewish community. Louis was gaining notoriety throughout the nation, particularly among African Americans living in Detroit. Both men faced their share of bigotry on the road against opponents. In Detroit, however, a city with an ailing economy and a strong need to pull together behind a common fandom, the Tigers and Joe Louis created a wide sense of belonging. Tiger manager Mickey Cochrane feigned sparring with Joe Louis in a memorable photo from 1937. Detroit was fighting through the Depression, but its citizens pulled for all of their athletes to do well.

The Detroit fans and players knew that Cochrane was the missing ingredient when his contract was acquired in December of 1933. Charlie Gehringer said of him, “Mickey Cochrane was the second hardest loser I ever saw (Cobb was the first), and the smartest manager. When he managed from the bench, he never made a mistake, never! And he was tough behind the plate. He’d throw the ball back to Schoolboy Rowe harder than Rowe threw it to him. Schoolie would get a little lazy out there but Cochrane would wake him up every time.”1 In 1934 the Tigers won the American League pennant, but lost in the World Series, to the St. Louis Cardinals. The Tigers won the World Series the following year, defeating the Chicago Cubs.

Joe Louis himself was a huge baseball fan. The Tigers were the inspiration for many of Detroit’s successful athletes of 1935. In boxing promoter Mike Jacobs’ New Jersey office, there was a conversation among his staff: “(Joe) Louis is nuts about the Tigers. He plays catch out at (boxing) camp every chance he gets. Gerald Walker is his favorite Tiger. He’s postponing his honeymoon so he can see the Tigers in the World Series.”2 Jacobs heard this conversation and ordered Louis’s handlers to put a stop to this threat to his payday, a coming fight with Max Baer. The fight with Baer in late September was one of Louis’s two huge fights that were received by telegraph from Yankee Stadium in staccato fashion, and tapped out by reporters in Detroit. Like a Hollywood movie, the newspaper came off the presses and was folded, stacked, bundled, and loaded onto trucks. “Extra! Extra! Read all about it!” was the newsboy cry heard all around Detroit the next morning as the papers were sold to workers throughout the city. Mass transit was still employed to move the workers. Street cars gave way to trolley buses that could provide curbside pickup and negotiate traffic in the increasingly congested Motor City.

Louis’s other Yankee Stadium victory had been in June against Primo Carnera. As the world’s heavyweight boxing champion for a record 12 years (1937-1949), Joe Louis was more universally admired than any African American man before him. Known as the Brown Bomber, he dominated prizefighting and forced America to re-examine its segregationist policies and attitudes. His fists destroyed the myth of white supremacy and his quiet dignity and exemplary patriotism opened the door for the wave of black athletes who followed.

Joe Louis Barrow, the son of an Alabama sharecropper, came to Detroit in 1926 at the age of 12. At 20 he quit his assembly-line job and became a professional fighter. During a 17-year career he compiled a 68-3 record, with 57 knockouts.

Some of Louis’s most famous bouts carried political overtones in the years before World War II. As Hitler and Mussolini seized power in Europe, Joe Louis destroyed their “master race” theories by defeating Italian giant Primo Carnera and German “superman” Max Schmeling. Columnist Jimmy Cannon immortalized Louis as “a credit to his race – the human race.”3

So to make the claim City of Champions, Detroit had to have champions in the most popular sports of the age, baseball and boxing, as well as champions in other sports that were just coming to Detroit. Football was well established at the University of Michigan, which was recognized as national champion in both 1932 and 1933. However, before 1934 there was no well-established professional football team in Detroit. Detroit’s National Football League franchise, after moving from Portsmouth, Ohio, as the Spartans, took the nickname Lions, in counterpoint with the Tigers, acknowledging that Detroit was “baseball crazy” for the other big cats. George Richards, owner of radio station WJR, led the effort to get an NFL team in Detroit. The Lions hosted their first Turkey Bowl at the University of Detroit Stadium. WJR radio broadcast the “clash of the titans” between the Lions and the Chicago Bears coast to coast. In 1935 WJR broadcast from “the golden tower of the Fisher Building” and become a 50-kilowatt station. This power level allowed the station’s signal to be heard all over the state of Michigan. Much like cable and satellite television today, radio brought fans to the sports teams and heroes of Detroit like never before. Earl “Dutch” Clark, the Lions’ first quarterback, led them to the NFL championship in 1935. After losing against the Green Bay Packers, 31-7, in their eighth game, the Lions found themselves in last place in the Western Division. The next week at home in Detroit, they beat the same Packers 20-10 with Clark leading the way as passer, punt returner, and kicker. The next two weeks saw the Lions tie the Bears in Chicago, and beat them convincingly on Thanksgiving Day in Detroit. The Lions finished their championship run against the New York Giants on December 15 with a 26-7 victory. The players were rewarded with Honolulu Blue parkas and a trip to Hawaii. However, they had to play publicity games in Denver and against all-star teams on their way to the islands. Calendar year 1935 was nearly over, but Detroit sports champions were still to be crowned.

The Detroit Red Wings were also crowned champions at this time. Detroit hockey teams first came to Detroit and played in Olympia Stadium in 1927 as the Cougars, then the Falcons, and finally the Red Wings, when the iconic winged-wheel logo was adopted in 1932. James Norris bought the team and stabilized its finances by limiting player salaries, and recognizing the hard-working and loyal hockey fans of Detroit in quelling any salary protests. Olympia remained the hockey venue until the opening of Joe Louis Arena in 1979.

The sport of hockey was a Canadian import of Charlie Hughes, a 1902 graduate of the University of Michigan and a sportswriter for the Detroit Tribune. He helped create the Detroit Athletic Club, and in 1926 he persuaded the club to pay the $100,000 franchise fee that started professional hockey in Detroit. In their first year, the National Hockey League’s Detroit Cougars lost $84,000 and finished with only 12 wins out of 44 games. Hughes decided to hire Jack Adams as general manager and coach. Adams remained GM until 1962.

The first few years were rough for the teams assembled by Adams because the majority of the fans attending the game in Olympia Stadium came over from Windsor, Ontario, and they had the bad habit of cheering for the Canadian visiting teams. In 1932 James Norris bought the team, the arena, and the club’s minor-league team, the Olympics, for the same $100,000 original entry fee. He renamed the Cougars the Red Wings, and designed the iconic winged wheel logo, in order to identify them as the “Motor City’s team.” The shrewd business sense of Norris and the eye for talent of Adams firmly established the Detroit hockey franchise as one of the strongest in professional sports. Ebbie Goodfellow was the Wings’ first superstar. He joined Detroit in 1929 and played for 14 seasons, and Jack Adams said of Ebbie, “He was Gordie Howe before there was a Gordie Howe.”4

The Red Wings won their first Stanley Cup at the conclusion of the 1935-36 season. When they clinched the Stanley Cup in Toronto, a heroes’ welcome awaited them at the Windsor train station, Michigan Central Station, and a procession to Olympia Stadium. To top it off, the Detroit Olympics won the International Hockey League Championship in October 1936, making the Tigers, Lions, and Red Wings hat-trick a grand slam of Detroit sports team victories.

A semipro sport that provided another champion to Detroit was bowling. Like Little Caesars Pizza founder (and future Tiger owner) Mike Ilitch’s softball team in the 1970s, in the ’30s the breweries sponsored bowling teams and leagues. The citizens and patrons of the beer industry treated the move of a good bowler from one sponsor to another as just as important news as a new beer or a new player for the Tigers. In 1933 Detroit’s Stroh Brewery, which provided beer at the Tigers games, backed a bowling team with Phil Bauman, John Crimmins, Cass Grygier, Walter Reppenhagen, and owner Joe Norris. The five had between them bowled 47 perfect games. Stroh’s team won the ABC National tournament in 1934 and the first five World Match Game titles in the 1930s. Beer and pizza are important to all sports fans, but especially Detroit.

Although Joe Louis was by far the most famous of the individual Detroit champions, he was by no means the first. Other emerging boxers from Detroit were Al Nettlow, the AAU 126-pound champ, and Dave Clark, the AAU 160-pound champion.

“Gar Wood is to the speedboat what Lindbergh is to the airplane,” said Bob Murphy of the Detroit Times.5 Wood had won the coveted Harmsworth Trophy five times over 15 years and pushed the world record for speed on water from 61 miles per hour in 1920 to 124 mph in 1932. He financed his dominance in the sport by profits from his mechanical inventions.

Detroit was home to legend of golf Walter Hagen, who captained the American Ryder Cup team to a victory over the British in 1935. Hagen won 11 major championships between 1914 and 1929, which as of 2014 still places him third behind Jack Nicklaus and Tiger Woods. In 1935, however, he was the greatest in history.

Detroit Cass Tech high-school graduate Eddie Tolan won the 100-meter and 200-meter sprints at the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics. Tolan was the first black athlete to win two Olympic Gold Medals, preparing as a member of the University of Michigan track team. In nearby Ann Arbor, Jesse Owens set three world records and tied another as a sophomore at the 1935 Big Ten Conference Championships held at the University of Michigan’s facility. Tolan won his Olympic Gold before Hitler’s 1936 Berlin games that made Owens so famous.

On April 18, 1936, a City of Champions Testimonial Dinner was held at Detroit’s Masonic Temple and was hosted by the Detroit Times. The cost of a ticket was $3. Letters of congratulations from the City Council and from the governor of Michigan declared it a Day of Champions for the 600 who attended.

Invited to the honors were many locally-based champions of their respective sports and games. Stanley Kratkowski was already the national middleweight lifting champion. The roll call of champions continued. Constance O’Donovan and Esther Politzer, national doubles tennis champions, and Katherine Hughes-Hallett, the Michigan and Midwest fencing champion, were present. Jake Ankom, the national amateur three-cushion billiards champion, and Newell Banks, who won the World’s Match Checker Championship, were both parlor-game champions who were recognized. Tom Haynie, the national medley swim champion, and the AAU national swimming champions from the Detroit Athletic Club were also there. Dick Degener of the University of Michigan was considered the top diver in the world and would win a Gold Medal in the three-meter springboard competition at the 1936 Olympic Games. Walter Kramer was the number-one badminton player in the United States in 1935 and would win the singles championship in 1938. Bill Bonthrom, who held the world record for the Olympic 1,500 meters, joined fellow track star Eddie “The Midnight Express” Tolan. Harry Joy, the national 20-gauge shotgun skeet shooting champion, and Tommy Milton, a two-time winner of the Indy 500, took bows. Another speedboat champion, Herbert Mendleson of Detroit, joined Gar Wood and his legendary mechanic Orlin Johnson at the testimonial.

Over the course of the evening, Potsy Clark, coach of the Lions, called his 1935 squad the greatest team ever assembled in football. Mickey Cochrane promised to fight for another championship, and Jack Adams introduced the Wings with a similar vow. The Wings actually delivered on another repeat championship, against the New York Rangers in 1937.

Finally, all the athletes praised the extraordinary fans of Detroit, who supported them despite the challenges of the Depression. Detroit fans have taken a strong sense of pride from their sports teams, and in return the athletes received that extra boost when playing at home.

LARRY and ROB HILLIARD were first told about Detroit being the City of Champions by their dad, Frank Hilliard, who was 24 years old in 1935. Detroit sports teams were an important part of their relationship growing up as brothers. Larry has great memories of the 1968 and 1984 Tigers teams, of Dave Bing (before he became the mayor of Detroit), of Thomas “Hit Man” Hearns, and of throwing the octopus onto the ice at old Olympia Stadium. These days Larry roots for the Tigers, Red Wings, Pistons, and Lions (especially OT Corey Hilliard) from his home in Maryland. He works at NASA as an electrical engineer. Rob, a retired welder in the auto industry, lives in Garden City, Michigan. His Detroit sports era featured Gordie Howe and Terry Sawchuck for the Red Wings, and Bobby Layne and Terry Barr for the Lions. While the Tigers were his favorite baseball team, his all-time favorite ballplayer is Ted Williams. The Detroit boxer that Rob admired was Sugar Ray Robinson.

Sources

Dyrson, Mark, and J.A, Mangan, eds., Sport and American Society (New York: Routledge, 2007).

Macdonnell, Leo, “Wings Rookie Scores After 176 Minutes,” Detroit Times, March 25, 1936.

Shaver, Bud, “Birth of a Fight Extra,” Detroit Times, June 26, 1935.

Guest, Conrad J., “When Detroit Was Known as the City of Champions,” Detroit Athletic Co., blog.detroitathletic.com/2012/12/20/when-detroit-was-the-city-of-champions/, accessed February 4, 2014.

“How the Great Depression Changed Detroit,” Detroit News, blogs.detroitnews.com/history/1999/03/03/how-the-great-depression-changed-detroit/, accessed September 14, 2013.

Windsor Daily Star

Aaregistry.org

Detroithistorical.org

Mgoblue.com

Notes

1 Charles C. Avison, Detroit: City of Champions (Detroit: Diomedea Publishing. 2008), 24.

2 Bob Murphy, “Stop Playing Catch, Jacobs Tells Joe,” Detroit Evening Times, September 20, 1935.

3 Avison, 20.

4 Avison, 82.

5 Avison, 111.