1947 Dodgers: The suspension of Leo Durocher

This article was written by Jeffrey Marlett

This article was published in 1947 Brooklyn Dodgers essays

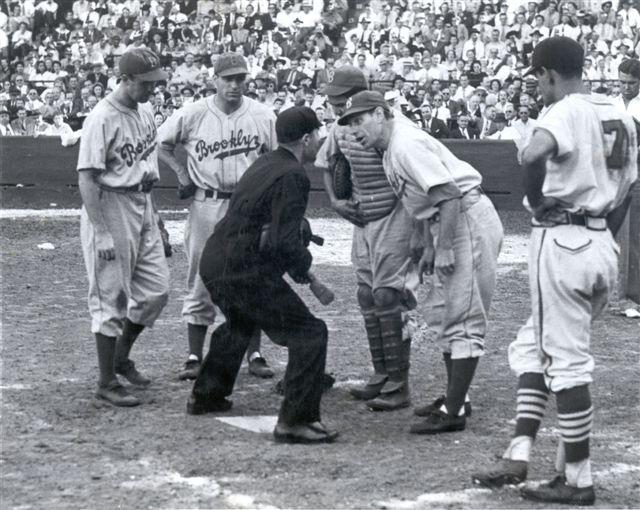

Leo Durocher made the cover of Time magazine just once: the April 14, 1947, issue. Published the day before Jackie Robinson broke into the major leagues with the Brooklyn Dodgers, the Time article did not cast the Dodgers’ manager in a kind light. The words “I don’t want any nice guys on my ball club” ran beneath Leo’s portrait. The background picture depicted Leo giving an umpire an earful of abuse, standard operation procedure for the manager nicknamed “The Lip.”

Just five days earlier Durocher had been suspended from baseball for a year. Commissioner Albert “Happy” Chandler cited Durocher’s string of moral shortcomings: gambling debts, associations with known gamblers and nightlife figures, and a scandalous marriage with charges of adultery, bigamy, and contempt of court. Brooklyn owner and general manager Branch Rickey often said Leo possessed “the fertile ability to turn a bad situation into something infinitely worse,” but Leo seemed finally to have hit rock bottom.1 Outside of Brooklyn, many baseball fans and observers gloated. Dodgers’ fans were devastated. Durocher’s suspension was shaping up as baseball’s “story of the year” before the season had even started.2

Then Robinson took the field in Brooklyn. Led by Burt Shotton, a sort of anti-Durocher, the Dodgers won the pennant. They pushed the Yankees to a seventh game before losing the World Series. Leo and his troubles had quickly receded into memories of spring training. The 1947 season could have provided an opportunity for Durocher to shine along with Brooklyn’s new star. Instead, the Time cover would be the highlight of Durocher’s 1947 season. His unerring ability to find trouble and draw attention removed him from a landmark season in baseball history.

When he broke into the American League, Leo Durocher gained notoriety for his brash actions as well as his quick glove. In 1928, at the age of twenty-two, he was playing shortstop for the New York Yankees, yet he was garnering more attention from his sartorial and off-field choices. Before that first season was a month old, Yankees manager Miller Huggins had to reprimand the young Durocher for brashly overdressing. Leo might have made rookie money but he spent profligately, routinely overdrawing his bank account. Leo acquired his nicknames “The Lip” and “the All-American Out” from Babe Ruth himself. Before the 1928 season concluded, Ruth also accused Durocher of stealing his watch.3

Durocher’s financial troubles followed him after his trade to Cincinnati in 1930. Gambling opportunities beckoned from Kentucky, just across the Ohio River. When traded to St. Louis during the 1933 season, he needed the Cardinals’ general manager, Branch Rickey, to cover his outstanding debts. During the 1934 season, Durocher married an independent and wealthy local businesswoman, Grace Dozier, with Rickey’s permission and blessing. Eventually, though, Leo reverted. Things didn’t change much when he was traded to Brooklyn before the 1938 season. His spending and gambling habits continued apace, but nobody could deny his will to win. After a year team president Larry MacPhail appointed him manager for the 1939 season.

Dodgers broadcaster Red Barber once wrote about the 1947 season: “Try to untangle Durocher from either Rickey or MacPhail and it’s no story.”4 Barber had a point. Durocher’s 1947 season-long suspension resulted partially from the ongoing feud between the two baseball executives. Both had handled Durocher as a player; in fact, Rickey had orchestrated with MacPhail Durocher’s trade to Brooklyn. When MacPhail entered the Army after the 1942 season, Rickey took over as Brooklyn’s team president. That meant he had Durocher on his hands again, now as a player-manager. Durocher had led the Dodgers to the 1941 pennant, two second-place finishes (1940, 1942), and a third-place finish in his inaugural season. After Rickey took over, the Dodgers stumbled, finishing third twice and even falling as far as seventh in 1944. By 1946 Leo had led the Dodgers back to second place, narrowly losing the pennant again to the Cardinals.5

Rickey biographer Lee Lowenfish writes that even as the 1946 season ended, Rickey recognized that his manager still swam in dangerous waters. Actor and avid gambler George Raft’s friendship with Durocher seemed worrisome.6 During his climb to Hollywood fame, Raft had befriended several baseball stars. With Durocher, though, Raft had found a true buddy—a quick-witted, gambling, nightlife-loving buddy. Raft and Durocher stayed at each other’s apartment when visiting the other’s home city. Raft once said: “We used each other’s suits, ties, shirts, cars, girls.”7 In 1944, with Durocher away at spring training in nearby Bear Mountain, New York, Raft hosted a gambling night at Leo’s apartment during which a wealthy patron lost several thousand dollars in a rigged craps game. By 1946 rumors had surfaced connecting Durocher and Raft with New York mobsters Joe Adonis and Bugsy Siegel. The Brooklyn district attorney’s office had tapped Durocher’s telephone, and the manager’s name had surfaced amid a check-cashing scandal at the Mergenthaler Linotype Company in Baltimore.8

Westbrook Pegler, a syndicated columnist for the New York Journal-American, had seen enough. In October 1946 he began a series of articles decrying Raft and Durocher as threats to society. In a phone conversation with Rickey, Pegler proclaimed Durocher a “moral delinquent” who would eventually “drag Rickey and baseball down to his own level of shame and shameful companions.”9 As Lowenfish writes, “Rickey could not effectively say to Leo Durocher, ‘You must cut all ties to George Raft.’ Somebody else would have to do it.”10 In November, Rickey sent Arthur Mann, his new assistant, to Chicago to arrange a meeting between the commissioner and Durocher. Mann told Chandler of Rickey’s wish:

Any reasonable method for telling Durocher emphatically that he must sever connections of all kinds with people regarded as undesirable by baseball—gangsters, known gamblers, companions of known gamblers, and racketeers. Regardless of names or identity, anybody whose reputation could hurt Leo or baseball.11

Chandler finally tracked Durocher down at an NBC studio where Durocher was rehearsing for a spot on the Jack Benny radio show. Chandler insisted that Durocher meet him on November 22 at the Claremont Country Club in Berkeley, California. Mann returned to Brooklyn, presuming his confidential business concluded.12

At the appointed time, Chandler and Durocher strolled across the greens. The commissioner produced a list of those whom Leo should avoid at all costs. Arthur Mann writes:

“Raft, Adonis, Siegel, Engelberg, etc.—a special coterie of men to avoid; and Leo readily agreed, even though it meant cutting off some apparently harmless associations of nodding acquaintance. Chandler was firm, but not threatening. He told Leo that the time had come to choose between undesirables and baseball, to halt wagging tongues; that there would be no trouble if he, Durocher, created none.”13

Leo acknowledged that the break would be difficult, but worth it. Chandler seemed satisfied. However, at just this moment, Leo sprang something new on the commissioner. He told Chandler about his love affair with the actress Laraine Day. They would be married just as soon as her divorce was final. Leo neglected to tell the commissioner that when he first met Laraine in 1942, he also was married. (His divorce from Grace Dozier went through in 1943.)14

Chandler hoped the furor could be contained, but in January 1947, Day and Durocher’s marriage hit the headlines. Day had filed for divorce from her husband, Ray Hendricks, a bandleader and manager of the Santa Monica airport. Hendricks accused Durocher of stealing Day’s affections. The press loved it. A divorce settlement soon was reached, but the California divorce decreed a year’s wait before Day could remarry. However, Day darted across the border to Juarez, Mexico, to obtain a “quickie divorce.” She then returned to El Paso, Texas, and married Durocher the same day, January 21, 1947.

As Arthur Mann wrote: “Could Chandler understand and appreciate that, more often than not, Durocher would parlay a simple situation into a complex problem through abysmal thoughtlessness?”15 Meanwhile, Chandler found himself facing unwanted and unpleasant comparisons to his predecessor, Judge Landis. Chandler’s unwillingness to tackle Durocher preemptively stood in contrast to Landis’s swift and stern punishments for those he discovered gambling on baseball.

With Day and Durocher’s marriage, the simmering scandal threatened to boil over. Judge George Dockweiler, who had granted Day’s interlocutory divorce decree, now considered charging her with adultery. In the eyes of the California court, Day remained married to Hendricks. With her actions in Texas, she now had two husbands. Durocher realized that Dockweiler had capitalized on their celebrity status to make his point. Dockweiler admitted he would not have pressed another, less recognized couple so hard. “That judge,” Leo proclaimed to the press, “is nothing more than a pious, Bible-reading hypocrite.”16 Eventually Dockweiler was removed from the case, and Day and Durocher remarried in California in 1948.17

At the time, though, the scandal surged ahead. Leo’s marital fanfare drew the attention of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Frank Murphy. A former governor of Michigan, mayor of Detroit, and lifelong bachelor, Murphy devoutly practiced his Roman Catholic faith. He gladly wore the mantle of the top court’s morality crusader. Murphy urged Commissioner Chandler to take swift and permanent action, reminiscent of Landis’s tenure, against the unrepentant Durocher.

Just after the 1946 season the Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn had threatened Rickey that the Brooklyn Catholic Youth Organization would boycott Dodgers games. CYO members constituted the largest block of the Dodgers’ Knothole Gang, a youth outreach endeavor Rickey had begun in Brooklyn as he had in St. Louis. Church groups were solicited to make attending baseball games part of their moral and social recreation programs. A CYO boycott of Dodgers games would greatly reduce attendance at Ebbets Field. As national president of the CYO, Justice Murphy went even further, threatening Chandler with a nationwide CYO ban on baseball. On March 1, 1947, the Brooklyn CYO made good on its threat and withdrew from the Dodgers’ Knothole gang.18

Meanwhile, the Dodgers prepared for spring training in Havana, Cuba. Durocher tried being on his best behavior, but found it tough going when he kept meeting old friends like Memphis Engelberg and Connie Immerman. Durocher and Immerman knew each other from the 1920s, when the young Yankees shortstop frequented the Cotton Club. Now Immerman was managing a new casino in Havana. Engelberg, a well-known New York area horse handicapper, was a good friend of both Durocher and Charlie Dressen, who was now coaching with the Yankees.19

Writing thirty-five years later, Red Barber pointed out an important but often ignored precedent to Chandler’s decision. On April 3, 1947, Bert Bell, commissioner of the National Football League, made public his belated decision to suspend indefinitely two New York Giants football players, Merle Hapes and Frank Filchock. Gamblers had offered the two players bribes to throw the 1946 championship game. Hapes and Filchock took a week to notify team officials. News of the attempted bribery made headlines on December 5, the morning of the game (which the Giants lost to the Chicago Bears, 24-14). Even though the two players’ culpability lay in their delayed response to the bribes, Bell took a few months to respond. His decision to suspend Hapes and Filchock indefinitely was the harshest punishment for professional athletes since Landis’s suspension of the eight Black Sox players in 1921. New York’s sportswriters reacted positively to Bell’s strong (if not necessarily swift) decision. Barber thus mused: “Did Chandler note the widespread approval that Bell received, or had Chandler made up his mind on his decision before April 3? Was Bell’s decision, and its timing, the final nail in the lid of Durocher’s coffin?”20

These forces—the nation’s ongoing concern about gambling in baseball and other sports, Chandler’s ascension to baseball commissioner, Rickey’s simmering feud with MacPhail, and Leo’s spotty record on non-baseball activities—provided the material causes for his suspension. As will be seen shortly, the efficient cause—the actual act that resulted in suspension—came in early April. The formal cause, though, remained Leo’s highly visible and public refusal to play according to “the rules” set down by baseball’s watchdogs. Historian Jules Tygiel has dismissed another commonly assumed formal cause: Chandler and MacPhail’s opposition to Rickey’s plan to integrate the Dodgers.21

Rickey had been planning to integrate the team since 1945 and had carefully chosen Army veteran and Negro Leagues player Jackie Robinson for the task. Leo actually played a small but pivotal role in assuring Robinson’s major-league debut. While training in Havana, the Dodgers traveled to Panama for a weekend series against some Caribbean All-Stars. Durocher learned that several Dodgers players had created a petition in opposition to Robinson. Durocher called a team meeting at midnight. The coaches assembled the team in an empty dining-hall kitchen. Still in his night robe, Leo told the players they could “wipe your ass” with the petition. Rickey, he assured them, would trade anybody unwilling to play with Robinson. For his part, Leo declared:

I’m the manager of this ballclub, and I’m interested in one thing: winning. . . . This fellow is a real great ballplayer. He’s going to win pennants for us. He’s going to put money in your pockets and money in mine. And here’s something else to think about when you put your head back on the pillow. From everything I hear, he’s only the first. Only the first, boys! There’s many more coming right behind him and they have the talent and they’re gonna come to play. . . . Unless you fellows look out and wake up, they’re going to run you right out of the ballpark.

Roger Kahn adds that Leo concluded: “Fuck your petition. The meeting is over. Go back to bed.”22 The short meeting speech captured Durocher’s meritocratic world view. Winning, especially financially lucrative winning, erased all surface differences.

That, Kahn has written, might have been Leo’s finest hour. Had he not been suspended for the entire 1947 season, Robinson would have enjoyed the support of Leo’s (in)famous commitment to winning.23 Leo’s willingness to engage umpires, opposing players and managers, and fans themselves would have buffered Robinson from at least some of the abuse he encountered.

The events leading to Leo’s suspension soon followed. In March 1947, the Yankees came to Havana for an exhibition series against the Dodgers. This meant Durocher’s good friend and former assistant, Charlie Dressen, now sat in the opposing dugout as a Yankees coach. The two friends had been teammates for two seasons on the Cincinnati Reds (1930 and 1931). Off the field, they both enjoyed card games and receiving horse-betting tips, especially from Memphis Engelberg.

Dressen’s defection to the Yankees had upset Durocher, and Leo characteristically, struck back. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle regularly ran a column titled “Durocher Speaks” so the Dodgers manager could weigh in on various issues. Harold Parrott, a former sportswriter now working for the Dodgers, actually ghost-wrote the pieces. The March 3 column claimed that because Yankees owner Larry MacPhail had failed to sign Durocher as the new Yankees manager he sought revenge by signing Dressen. With unreflective irony, Durocher accused the Yankees’ owner of unsportsmanlike conduct. Reverting to his Dodgers past when he routinely fired and rehired Durocher, MacPhail erupted, demanding that Commissioner Chandler punish the Dodgers manager.

Then Leo made things even worse. On March 9, in another game with the Yankees at Havana’s new Estadio del Cerro, Durocher noticed Engelberg and Immerman sitting directly behind the Yankees dugout. MacPhail had given them the choice seats and sat himself just a few feet away. Durocher immediately complained: “If I did that, I’d get kicked out of baseball.” Rickey too had noticed the same two characters in MacPhail’s box seats in the previous day’s game. Dick Young of the New York Daily News quoted Durocher complaining that MacPhail associated with the very same gamblers Leo had to avoid. In other words, Durocher viewed this situation as analogous to his confrontation with Judge Dockweiler: While Durocher must atone for every infraction, others were allowed to commit the same sins without fear of retribution.24

On March 16 MacPhail filed a protest charging Durocher and Rickey with slander. He also named Engelberg and Immerman as Durocher’s friends, implying that the manager still associated with gamblers. Chandler now had no choice. Durocher and Rickey had questioned the commissioner’s leadership as well as MacPhail’s off-field associations. Chandler called a meeting for March 24 with Durocher and MacPhail. After MacPhail finished reviewing the charges, Durocher apologized, claiming, “It’s all baseball jargon. I didn’t mean anything derogatory in that article about you. . . . I needled you, but it was purely baseball and nothing personal.” Durocher effectively admitted that he and Parrott had directed the column at Chandler’s decisions, not MacPhail himself or his friends (who, of course, were also Durocher’s!). Momentarily outgunned on the ball field, Leo had sought an advantage on his former boss. As he had several times as Dodgers owner, MacPhail tearfully embraced Durocher and claimed the incident finished. “You’ve always been a great guy with me and always will be a great guy. Forget it. It’s over,” MacPhail declared.25

It turned out MacPhail was wrong. At the same meeting, Durocher had reminded Chandler that the commissioner himself had named Engelberg and Immerman among those to be avoided.

Chandler responded by querying Leo about gambling in the Dodgers locker room. After Leo answered, Chandler then asked MacPhail if he had offered Leo the Yankees’ manager job. MacPhail stalled. Arthur Mann noted that Chandler did not ask Leo the same question. Chandler likewise did not rule on MacPhail’s charges. At a March 30 meeting, held with Rickey present, it became clear that Yankees management could have handed Immerman and Engelberg the tickets.

Rickey and co-owner Walter O’Malley considered the matter closed. However, they then received an ominous sign. Chandler dismissed MacPhail and then casually asked Rickey and O’Malley, “How much would it hurt you folks to have your fellow out of baseball?”26

Presuming order restored, the Dodgers returned to Brooklyn. Rickey set about finalizing the plans for Robinson to start on Opening Day at Ebbets Field. On April 9, while Durocher met with Rickey to discuss starting Robinson in an exhibition game that afternoon at Ebbets Field, Chandler telephoned with his decision. Both teams were fined $2,000 each for detrimental conduct. Harold Parrott was fined $500 and ordered to stop publication of “Durocher Speaks.” Dressen was suspended for thirty days for signing with the Yankees while still under contract with the Dodgers. Durocher was suspended from baseball for one year.27

Rickey exploded, repeatedly yelling, “You son of a bitch!” Durocher and Arthur Mann both knew something was wrong when the normally abstemious Rickey used such profanity. Leo, uncharacteristically, responded with only an indignant “For what?” Later Leo said, “To this day, if you ask me why I was suspended, I could not tell you. Neither could any sportswriter who followed the case.”28

The suspension made news nationwide. Dodgers’ fans regarded the decision as cowardice prompted by Chandler’s acquiescence to MacPhail who, according to Brooklyn fans, had instigated the affair. Arthur Daley wrote in the New York Times: “The Lip is in a comparable position to the chap hauled into traffic court for driving through a red light and then being sentenced to the electric chair.”29 Nationally, though, Leo’s suspension appeared as proof that repeat offenders could not always expect to escape punishment. The Catholic press took special glee in noting that Leo finally had his comeuppance.30

Durocher glumly accepted his fate, moving into a secluded house in the Santa Monica hills with Laraine Day. He occupied himself with yard work, the Hollywood night life, and following the Dodgers with Red Barber’s broadcasts. Rickey promised Leo his full year’s salary, and then named Burt Shotton as interim manager.31

Durocher glumly accepted his fate, moving into a secluded house in the Santa Monica hills with Laraine Day. He occupied himself with yard work, the Hollywood night life, and following the Dodgers with Red Barber’s broadcasts. Rickey promised Leo his full year’s salary, and then named Burt Shotton as interim manager.31

With Durocher gone, Robinson was left to face alone the racist opposition of men like Phillies manager Ben Chapman. Robinson’s teammates, led by Pee Wee Reese, embraced Robinson and provided instead a quieter, perhaps more stable, support than Durocher’s combat-ready mentality could have. It cannot be assumed that Robinson would have suffered less if Leo had not been suspended for 1947. Durocher and Robinson had their own conflicts in the 1948 season before Leo left to manage the archrival Giants.

In his memoirs, Chandler solely blamed Durocher. He had “run a thousand red lights,” Chandler said in reference to Daley’s remark.32 Later on, Dodgers chroniclers like Peter Golenbock and Roger Kahn would suggest that at least partial blame could be pinned on Walter O’Malley. The future Dodger owner repeatedly failed to defend Durocher successfully before Chandler and Brooklyn’s Catholic leaders.33 Durocher and others blamed Branch Rickey. Day repeatedly told Durocher, “That man is not your friend.” Rickey, according to Day, put up a pious front while watching to take any advantage.34 The Day-Durocher-suspension saga still receives attention from baseball aficionados. Day’s death in November 2007 rekindled interest, six months after Major League Baseball and the entire nation recognized the 60th anniversary of Robinson’s Opening Day start with the Dodgers.35

The 1947 season concluded with the Yankees beating the Dodgers in a tight seven-game World Series. After the final out, MacPhail sought out Rickey who politely shook hands while whispering a rebuke. MacPhail then went on a drunken rampage that involved fistfights and firing George Weiss, the Yankees’ farm director.36 When Chandler had asked Rickey and O’Malley how much it would hurt to lose Durocher, Rickey replied that Durocher “has more character than the fellow”—meaning MacPhail—“you just sent out of the room.”37

Durocher certainly committed his fair share of what might be called “surface crimes.” He gambled and allowed gamblers access to his players, and his personal life ran antithetically to the very traditional values baseball was supposed to represent and defend. When confronted with a deeper crime like the racism fueling the Dodgers’ petition, Durocher revealed his pragmatic, yet moral, side.38 What and who Leo defended that night in Panama became the lasting story of the 1947 season, not his suspension which began the season.

JEFFREY MARLETT teaches religious studies at The College of Saint Rose in Albany, New York. He is the author of “Saving the Heartland: Catholic Missionaries in Rural America, 1920-1960” (Northern Illinois University Press, 2002). He became interested in Leo Durocher while preparing undergraduate ethics courses.

Notes

1. Quoted in Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), p. 348.

2. See David Mandell, “The Suspension of Leo Durocher.” The National Pastime: A Review of Baseball History #27, Cleveland, Ohio: Society for American Baseball Research, 2007: pp. 101-4.

3. Leo Durocher, with Ed Linn, Nice Guys Finish Last. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1975. pp.. 46-47 (Huggins), 65 (Immerman), 48-55 (Ruth). Gerald Eskenazi, The Lip: A Biography of Leo Durocher (New York: William Morrow & Co., 1993), pp. 47-48.

4. Red Barber, 1947: When All Hell Broke Loose in Baseball, New York: Da Capo, 1982, p. 19. Eskenazi, The Lip, pp. 199-200.

5. http://www.baseball-reference.com/managers/durocle01.shtml accessed 28 November 2009.

6. Lowenfish, p. 407.

7. Lowenfish, p. 408.

8. Lowenfish, p. 408. See “$750,000 Swindle: Brooklyn clerk gravely steals a fortune to buy some of the good things of life for his family.” Life, November 18, 1946.

9. Arthur Mann, Baseball Confidential: Secret History of the War Among Chandler, Durocher, MacPhail, and Rickey (New York: David McKay Company, 1951), p. 38.

10. Lowenfish, p. 409.

11. Mann, p. 44.

12. Mann, pp. 43-44.

13. Mann, p. 46.

14. Mann, pp. 46-7; Eskenazi, pp. 174, 202-3; Happy Chandler, Heroes, Plain Folks, and Skunks: The Life and Times of Happy Chandler with Vance Trimble (Chicago: Bonus Books, 1989), pp. 206-7.

15. Mann, p. 29.

16. Roger Kahn, The Era 1947-1957: When the Yankees, the Giants, and the Dodgers Ruled the World. (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2002), pp. 27 (first quote), 28 (second).

17. Durocher, Nice Guys Finish Last, p. 235.

18. “Catholics Quit Dodgers Knothole Club in Protest over the Conduct of Durocher,” March 1, 1947, p. 17; “MANNERS & MORALS: Don’t You Want Me to Be Happy?”,(February 3, 1947).

Kahn, pp. 29 (Brooklyn CYO), 36-37 (Murphy and Chandler); Chandler, p. 213; Barber, p. 103.

19. Durocher, p. 245. Mann, pp. 71-2.

20. Barber, pp. 125-6 (quoted).

21. Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy 25th anniversary edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 177; Tygiel, Past Time: Baseball as History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), p. 113.

22. Durocher, p. 205. Kahn, p. 36.

23. Kahn, p. 35.

24. Lowenfish, Rickey, p. 421-2.

25. Quoted in Peter Golenbock, Bums: An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers 1984 (Chicago, IL: Contemporary Books, 2000), p. 101 (Durocher and MacPhail quotes); See also, Baseball Confidential, p. 102-4.

26. Lowenfish, Rickey, p. 424. Mann, Baseball Confidential, p. 102-15.

27. Louis Effrat, “Chandler Bans Durocher for the 1947 Baseball Season,” New York Times (April 10, 1947), p. 1, 31;

28. Lowenfish, Rickey, p. 425. Durocher, Nice Guys Finish Last, p. 257, 235 (emphasis in original).

29. Arthur Daley, “Sports of the Times: Chandler Flexes His Muscles,” New York Times, April 10, 1947, p. 32.

30. “Durocher Versus the CYO,” Catholic Digest 11 (June 1947): p. 96; reprint from The Catholic Mirror (April 1947).

31. Leo Durocher, The Dodgers and Me: The Inside Story (Chicago: Ziff-Davis, 1948), p. 273.

32. Chandler, p. 221.

33. Kahn, pp. 30, 265 (finances); Golenbock, Bums: An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers. (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1984), p. 105.

34. Durocher, Nice Guys Finish Last, pp. 270-1.

35. http://www.baseball-fever.com/showthread.php?t=70561

36. Kahn, pp. 140-2.

37. Mann, p. 114.

38. For the contrast between “surface” and “deep” crimes, see Carlo Rotella, Good With Their Hands: Boxers, Bluesmen, and Other Characters From the Rust Belt (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), p. 119.