1947 Yankees: Bill Bevens’ almost World Series no-hitter

This article was written by Joe Dittmar

This article was published in 1947 New York Yankees essays

With the favored New York Yankees leading the Brooklyn Dodgers two games to one, the clubs met for Game Four of the 1947 World Series at Ebbets Field. The thriller provided a storybook finish with tragic overtones. With the Yankees leading the 1947 World Series two games to one over the Dodgers, the two clubs met for Game Four in Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field. New York started Bill Bevens, a mediocre right-hander who was a few weeks shy of his thirty-first birthday. Bevens had been 16-13 for the Yankees in 1946 but slipped to 7-13 in the pennant year, the result of some bad luck and his seventy-seven walks in 165 innings pitched. For the Dodgers, rookie Harry Taylor, whose promising season had been curtailed by an elbow problem that sidelined him for five weeks in August and September, got the call.

With the Yankees leading the 1947 World Series two games to one over the Dodgers, the two clubs met for Game Four in Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field. New York started Bill Bevens, a mediocre right-hander who was a few weeks shy of his thirty-first birthday. Bevens had been 16-13 for the Yankees in 1946 but slipped to 7-13 in the pennant year, the result of some bad luck and his seventy-seven walks in 165 innings pitched. For the Dodgers, rookie Harry Taylor, whose promising season had been curtailed by an elbow problem that sidelined him for five weeks in August and September, got the call.

The Yankees wasted no time getting to Taylor. The first two batters, Snuffy Stirnweiss and Tommy Henrich, singled, and Yogi Berra reached first on an error by shortstop Pee Wee Reese. A walk to Joe DiMaggio forced in a run and sent Taylor to an early shower. Hal Gregg assumed the pitching duties for Brooklyn and extinguished the rally on a pop-up and a double play grounder. In the home half of the first the Dodgers worked Bevens for two walks, but both runners were left stranded.

In the third, after DiMaggio walked, George McQuinn tapped a ball near the plate that catcher Bruce Edwards threw wildly to first. DiMaggio, on a sign from third base coach Chuck Dressen, tried to score on the errant throw but was cut down easily at the plate. Dressen’s decision to send DiMaggio home on the play provided the second-guessers with ample grist during the following few days.

In the bottom of the third the Dodgers’ Eddie Stanky led off with a walk and advanced to second on a Bevens wild pitch. But Johnny Lindell helped the Yankees escape damage with a tumbling catch of Jackie Robinson’s foul fly. New York added an insurance run in the fourth when Billy Johnson tripled and Lindell doubled him home. It was 2–0, Yankees.

The Dodgers finally took advantage of Bevens’s wildness in the fifth. The first two batters, Spider Jorgensen and Hal Gregg, walked. Although the Dodgers had yet to hit safely, they now had six free passes from the big right-hander. Stanky sacrificed both runners into scoring position. Pee Wee Reese then sent a ground ball to shortstop Phil Rizzuto, who tossed out Gregg running to third. But Jorgensen scored. It was now 2–1, Yankees.

The Dodgers finally took advantage of Bevens’s wildness in the fifth. The first two batters, Spider Jorgensen and Hal Gregg, walked. Although the Dodgers had yet to hit safely, they now had six free passes from the big right-hander. Stanky sacrificed both runners into scoring position. Pee Wee Reese then sent a ground ball to shortstop Phil Rizzuto, who tossed out Gregg running to third. But Jorgensen scored. It was now 2–1, Yankees.

Hank Behrman replaced Gregg on the mound for Brooklyn in the eighth. Behrman withstood an error by Jorgenson in that inning, but ran into serious trouble in the ninth. With Rizzuto on first, Bevens sacrificed, but both he and Rizzuto were safe when the throw to second was late. When Stirnweiss singled to center, the Yankees had the bases loaded and a golden opportunity to put the game out of reach.

Brooklyn called in its ace reliever, Hugh Casey, to face the always dangerous Henrich. On Casey’s first pitch, Henrich grounded sharply back to the hurler, who started a snappy pitcher-to-catcher-to-first double play, pulling the Dodgers out of potential disaster. They still had no hits but were only one run down entering the do-or-die bottom of the ninth.

Bevens’s high-wire act finally caught up with him in the strategy-filled, fatal ninth. After Bruce Edwards flied out, Carl Furillo collected the Dodgers’ ninth walk. When Jorgensen fouled out, Bevens was one out away from the first World Series no-hitter. Al Gionfriddo, running for Furillo, stole second. This changed the Yankees’ thinking about pitching to Pete Reiser, who was batting for Casey. Although the talented outfielder was injured and couldn’t run well, New York decided to walk him. It was the tenth walk for Brooklyn and a disaster-inviting strategy—putting the winning run on base. Eddie Miksis ran for Reiser.

Bevens’s high-wire act finally caught up with him in the strategy-filled, fatal ninth. After Bruce Edwards flied out, Carl Furillo collected the Dodgers’ ninth walk. When Jorgensen fouled out, Bevens was one out away from the first World Series no-hitter. Al Gionfriddo, running for Furillo, stole second. This changed the Yankees’ thinking about pitching to Pete Reiser, who was batting for Casey. Although the talented outfielder was injured and couldn’t run well, New York decided to walk him. It was the tenth walk for Brooklyn and a disaster-inviting strategy—putting the winning run on base. Eddie Miksis ran for Reiser.

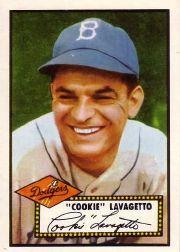

The cat-and-mouse game reached another level when, for only the second time this season, right-hand-hitting Eddie Stanky was lifted for a pinch hitter. Cookie Lavagetto, who also batted from the right side, was an aging veteran who had seen limited action during the season. He swung at the first pitch and missed, leaving Bevens only two strikes away from victory and fame. But Lavagetto drilled the next offering off the right-field wall. The ball bounced around long enough for Gionfriddo to score the tying run and Miksis to tally the game-winner.

As his near fame turned into an unforgettable loss, Bevens’s locker-room quote never rang truer: “Those bases on balls sure kill you.” Bevens came back to pitch 2 2/3 scoreless relief innings in the Yankees’ triumphant Game Seven. That was the final game of his four-year Major League career. It was also the final game of Lavagetto’s career.

JOE DITTMAR, a corporate trainer in the pharmaceutical industry, has been a leader in the SABR Connie Mack Chapter and was vice chairman of the Records Committee for 18 years. In addition to numerous articles published in SABR’s “The National Pastime” and “Baseball Research Journal”, he has authored “Baseball’s Benchmark Boxscores,” “The 100 Greatest Baseball Games of the 20th Century Ranked,” and the Sporting-News/SABR Research Award-winning “Baseball Records Registry: The Best and Worst Single-Day Performances and the Stories Behind Them.” Joe also teaches a baseball history class at his local community college.