1947 Yankees: Reynolds and Raschi, building blocks of a dynasty

This article was written by Sol Gittleman

This article was published in 1947 New York Yankees essays

Two pitchers emerged in the New York Yankees’ remarkable 1947 season who would lead the team to unprecedented success: Allie Reynolds and Vic Raschi.

The 1947 season for the New York Yankees was expected to be another step down in the decline of the franchise. Joe DiMaggio and Joe Gordon had returned from the military in 1946, but both had subpar years. For the first time in his career, DiMaggio batted below .300 and failed to drive in 100 runs. Gordon, the league’s most Valuable Player in 1942, batted an anemic .210. Ace pitcher Spud Chandler was a 20-game winner in 1946, but he was now 38 years old. New York finished 17 games behind the Boston Red Sox, who were prohibitive favorites to repeat in 1947.

The 1947 season for the New York Yankees was expected to be another step down in the decline of the franchise. Joe DiMaggio and Joe Gordon had returned from the military in 1946, but both had subpar years. For the first time in his career, DiMaggio batted below .300 and failed to drive in 100 runs. Gordon, the league’s most Valuable Player in 1942, batted an anemic .210. Ace pitcher Spud Chandler was a 20-game winner in 1946, but he was now 38 years old. New York finished 17 games behind the Boston Red Sox, who were prohibitive favorites to repeat in 1947.

It never happened. In 1947 the Red Sox collapsed to a third-place finish, and the New York Yankees rode a midseason 19-game winning streak to capture the pennant by 12 games over Detroit, then beat Brooklyn in a tense seven-game World Series. After falling to third place in 1948, the Yankees went on to win an astounding five consecutive World Series championships from 1949 to 1953. Two pitchers emerged in that remarkable 1947 season who would lead the Yankees to this unprecedented success: Allie Reynolds and Vic Raschi.

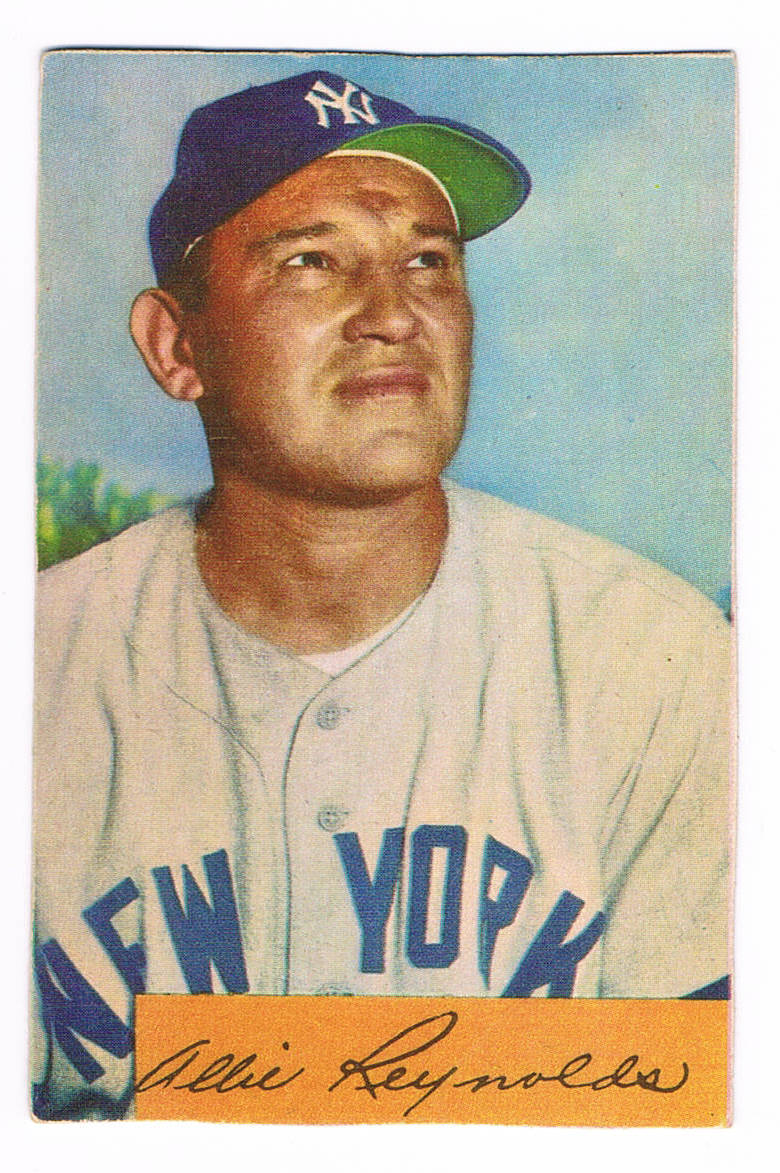

Doubtless few saw it coming after the 1946 season. In October, Yankees President Larry MacPhail traded Gordon to the Cleveland Indians for the under-achieving 29-year-old Reynolds, who was coming off a disappointing 11-15 season. Reynolds, who was part Creek Indian, had been dubbed “The Vanishing American” in Cleveland because of his inability to pitch complete games.

In an effort to solve the Yankees first-base problems, MacPhail signed 37-year-old free agent George McQuinn in January. McQuinn was coming off a year in which he hit .225 for the last-place Philadelphia Athletics, who released him at the end of the 1946 season. Eyes rolled at the thought of a Yankees first baseman arriving after being released by a last-place team.

Manager Bucky Harris set his 1947 starting rotation with Reynolds third, behind Chandler and right-hander Bill Bevens. The fourth starter was an inconsistent, hard-throwing left-hander who enjoyed the nightlife a little too much: Joe Page. Soon rookie Spec Shea moved into the fourth spot, and Page was exiled to the bullpen, and in Harris’s mind, as his patience ran out, would soon be pitching for the Class Triple-A Newark Bears.

When Boston came into Yankee Stadium on May 23 for a four-game series, New York seemed stuck at a mediocre 13-14. The Red Sox, at 17-12, were positioned to make a move on front-running Detroit, who, led by pitchers Hal Newhouser, Fred Hutchinson, and Dizzy Trout, had jumped out to a 17-8 record and the league lead.

In four Major League seasons with Cleveland, Reynolds never fulfilled the promise that management hoped for when they signed him off the Oklahoma A&M campus in 1939. His wife and two children afforded him an exemption from military service, and by 1942 Cleveland was looking for a replacement for their ace Bob Feller, who had enlisted soon after Pearl Harbor. In spite of stamina and control problems, Allie got the call to report to Cleveland for the end of the 1942 season. From then on, it was a roller coaster ride, resulting in a 51-47 record when the Indians finally gave up on him.[fn]Reynolds was eventually diagnosed with diabetes, and large doses of orange juice in 1947 solved his stamina problems.[/fn]

In four Major League seasons with Cleveland, Reynolds never fulfilled the promise that management hoped for when they signed him off the Oklahoma A&M campus in 1939. His wife and two children afforded him an exemption from military service, and by 1942 Cleveland was looking for a replacement for their ace Bob Feller, who had enlisted soon after Pearl Harbor. In spite of stamina and control problems, Allie got the call to report to Cleveland for the end of the 1942 season. From then on, it was a roller coaster ride, resulting in a 51-47 record when the Indians finally gave up on him.[fn]Reynolds was eventually diagnosed with diabetes, and large doses of orange juice in 1947 solved his stamina problems.[/fn]

Soon after the 1947 season began, a new Reynolds emerged. In the first of the four-game weekend series, he shut out the Red Sox, 9–0, on two hits. It was the kind of “Big Game” performance that became the hallmark of Allie Reynolds in his New York Yankees incarnation. In the next three games, Chandler, Bevens, and Page handed Boston three more losses.

The Yankees had found their ace. Allie Reynolds became Harris’s stopper. He faced the best of the Boston and Detroit staffs for the rest of the season, led the Yankees in starts (30), complete games (17), and was the only starter with more than two hundred innings pitched (242). His record was 19-8 with an ERA of 3.20. He also showed Harris that he could work in between starts; Reynolds relieved four times and got the first two of his 41 saves as a Yankee.

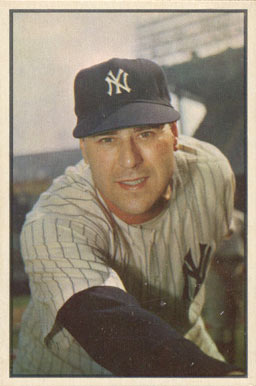

Vic Raschi, 28 years old and languishing in the Pacific Coast League with the Portland Beavers in 1947, was ready to quit baseball. The Yankees had signed him in 1938 after the high-school star turned down a football scholarship to Ohio State. Farm director George Weiss had promised Raschi’s immigrant parents the club would pay for Vic’s college education; the new Yankees recruit enrolled at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, in the fall. After three seasons starring on the college baseball team, Raschi was ordered to report to the Amsterdam (New York) Rugmakers of the Class C Canadian-American League in 1941 after William and Mary’s season was complete.

His professional career was under way. After the 1942 season with the Norfolk (Virginia) Tars of the Class B Piedmont League, Raschi enlisted in the Army Air Force. For the next three years he moved all over the country as a physical-fitness trainer. He finally got back to Williamsburg in 1945 to marry his college sweetheart. When he was discharged, he was 27 years old, and time was running out. After a 1946 season with the Class A Binghamton (New York) Triplets and Newark in the International League, Raschi got a September call-up to the big club; he was ready. He had two starts against the last-place Athletics and won both, going the distance each time.

When Raschi reported to spring training in 1947, he thought he had won a roster spot on the basis of his late-season performance. But Harris had turned the responsibility for pitchers over to coach Charlie Dressen, an old-time National League infielder and later manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Dressen thought he knew everything about pitchers and their make-up.[fn]Charlie Silvera, backup catcher to Berra during the great Yankees years, came up in 1949 and knew Dressen from the Pacific Coast League. His comment on Dressen as a pitching coach: “Dressen thought he knew everything about pitching, and he knew nothing. He would stop and tell the pitchers what they were doing wrong. He almost ruined Reynolds.” (Interview, August 19, 2004) Reynolds also had no use for Dressen: “Dressen would make himself look good by making you look bad.” (Phil Rizzuto and Tom Horton, The October Twelve, 168) Ralph Branca, who pitched for Brooklyn when Dressen managed there in 1951, referred to him as “that piece of dreck Dressen,” using a very unflattering Yiddish expression. Branca was not Jewish, but he found the right word. (Roger Kahn, The Era, 1947-1957, 107).[/fn] He used Raschi exclusively as a batting-practice pitcher during spring training, and before the season started, Vic was told to report to Portland of the Class Triple-A Pacific Coast League. The other two call-ups from Newark in September 1946, Yogi Berra and Bobby Brown, had made the team; Raschi, however, was going back to the minors.

When Raschi reported to spring training in 1947, he thought he had won a roster spot on the basis of his late-season performance. But Harris had turned the responsibility for pitchers over to coach Charlie Dressen, an old-time National League infielder and later manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Dressen thought he knew everything about pitchers and their make-up.[fn]Charlie Silvera, backup catcher to Berra during the great Yankees years, came up in 1949 and knew Dressen from the Pacific Coast League. His comment on Dressen as a pitching coach: “Dressen thought he knew everything about pitching, and he knew nothing. He would stop and tell the pitchers what they were doing wrong. He almost ruined Reynolds.” (Interview, August 19, 2004) Reynolds also had no use for Dressen: “Dressen would make himself look good by making you look bad.” (Phil Rizzuto and Tom Horton, The October Twelve, 168) Ralph Branca, who pitched for Brooklyn when Dressen managed there in 1951, referred to him as “that piece of dreck Dressen,” using a very unflattering Yiddish expression. Branca was not Jewish, but he found the right word. (Roger Kahn, The Era, 1947-1957, 107).[/fn] He used Raschi exclusively as a batting-practice pitcher during spring training, and before the season started, Vic was told to report to Portland of the Class Triple-A Pacific Coast League. The other two call-ups from Newark in September 1946, Yogi Berra and Bobby Brown, had made the team; Raschi, however, was going back to the minors.

Instead of reporting, a bitter and discouraged Raschi returned to his wife, Sally, in upstate New York to tell her he was finished. The Yankees called him twice, threatened to ban him for life unless he reported. Raschi had the personality make-up of a stubborn bulldog, and he was not fazed by threats. Sally Raschi, who understood her husband, brought a calm, deliberate resolution to the crisis: “I’ve never seen Portland, so let’s go.” It was the most important decision of their lives.

After settling into an apartment, Raschi went over to the stadium, found the manager’s office, knocked, entered, and saw a tall man walking toward him with an outstretched hand and a face he could trust. It was Jim Turner; this was to be a friendship for life. Turner, consummate mentor of pitchers, knew that this big, dour, hard-throwing pitcher had all the equipment: four-seam fastball, curve, slider, and change-up. Turner also noticed that at a critical moment, some .220 hitter would sit on Raschi’s fastball and beat him. Vic needed to pitch inside, push the batter off the plate, but his brother Gene lost his sight after being beaned, and Raschi had a fear of hitting someone in the head. Turner worked on him. He knew that eventually any Major League hitter would catch up with any fastball; there was only one way to guarantee that the pitcher owned the plate, not the hitter: through intimidation, and that meant pitching “up and in.”

It was through Turner’s tutelage in this period at Portland that Raschi developed a terrifying scowl, a withering look that opposing teams, journalists, and even teammates came to appreciate—and fear. When they saw “the look” on Raschi’s face, they stayed away. By the time Jim Turner was finished with his course of instruction, no one would come near Vic Raschi on the day that he pitched.[fn]Raschi’s “look” actually took the place of his pitching “up and in.” Of the three Yankee greats of those teams, Vic hit the fewest batsmen in his career, a total of twenty-six, far fewer than Allie Reynolds’ fifty-seven and even control pitcher Ed Lopat’s forty-three. Reynolds would terrify opposing hitters with a fastball under the chin; Raschi would terrify them with his “look.” Lopat would plunk any hitter who thought he was getting too smart for his own good. None of them approached the numbers of someone like Don Drysdale, who delighted in hitting 154 batters in his career.[/fn]

In July Turner called Weiss and told him to get Raschi back to the Yankees. Weiss, who knew Turner was one of the most astute evaluators of pitching talent, didn’t waste any time. The Yankees were in the middle of their extraordinary win streak, but were running out of arms. Weiss recalled Raschi on the same day in July that he acquired 39-year-old veteran Bobo Newsom.

The two newcomers pitched in tandem, winning doubleheaders in games 13 and 14 of the streak, and again in 18 and 19, the final two of the streak. When Raschi walked into the Yankees clubhouse on that July day, he knew most of the faces from his brief stint at the end of the ’46 season. But he looked for a new one in particular, Allie Reynolds, and a friendship was forged that lasted the rest of their lives.

Raschi started 15 games in that half-season of 1947, completed six and finished with a 7-2 record. Not even Charlie Dressen could stop his march to Yankees greatness. In his eight years with New York, his record was 120-50 for a win-loss percentage of .706, second only to Spud Chandler in Yankees history. After winning 19 games in 1948, Raschi won 21 games in each of the 1949, 1950, and 1951 seasons. In World Series competition he was 5-3; two of those losses were 1–0 and 3–2. His Series ERA is 2.24.

Like his friend Allie Reynolds, he would go on to become a big-game pitcher, winning the pennant clincher in the last game of the 1949 season and World Series final games in 1949 and 1951.

Neither Reynolds nor Raschi was the star of the 1947 World Series. That role was left to Joe Page. Reynolds went all the way in a second-game 10–3 victory for his only win. Raschi was used exclusively in relief, a role in which he never enjoyed success.

That season was prelude to one of the most unexpected runs in baseball history, and Allie Reynolds and Vic Raschi were on center stage for those five years between 1949 and 1953.

The unforeseen Yankees’ success of 1947 did not change the opinion of baseball writers who were convinced that the season had been an aberration. That sentiment seemed to be confirmed in 1948 when the Red Sox apparently regained their equilibrium, only to be deposed in a one-game playoff by the upstart Cleveland Indians. One historian wrote: “The Yankees showed every sign of having crumbled before the start of the [1949] season. The Bombers had fallen to third place, age was slowing up several key pinstripers, and both Cleveland and Boston seemed stronger on paper than their 1948 contending squads.”[fn]David S. Neft and Richard M. Cohen, Baseball, The Sports Encyclopedia, 14th edition, 278.[/fn]

In February 1948 George Weiss, by then the general manager, traded his starting catcher, Aaron Robinson and two other players, for Chicago White Sox left-hander Ed Lopat. Weiss fired manager Bucky Harris, hired Casey Stengel, and Weiss and Stengel agreed the best potential pitching coach in baseball was the manager of the Portland Beavers, Jim Turner. They also knew much depended on turning Yogi Berra into a respectable catcher.[fn]At the start of the 1949 season, there was still uncertainty about Berra. The Opening Day catcher was Gus Niarhos, and Berra was on the bench.[/fn] That project was turned over to future Hall of Famer Bill Dickey and the three veteran pitchers who would lead the New York Yankees on to unprecedented glory: New York’s Big Three, a team within a team: Allie Reynolds, Vic Raschi, and Ed Lopat.

In addition to Raschi’s 120 victories, Reynolds was 131-60, with two no-hitters with the Yankees. In his eight years with New York, Ed Lopat produced a 113-59 record, a .657 winning percentage, and an ERA of 3.19. Collectively, they won 16 of the Yankees’ 20 World Series victories between 1949 and 1953. Either Allie or Vic was the winning pitcher or got the save in each of the final games of those five World Series. But, “In the Beginning” was the 1947 season that few saw coming.

SOL GITTLEMAN graduated from Drew University in 1955. After a promising college baseball career, he was shown the scouting report written by a part-time bird dog covering colleges in northern New Jersey: “Too small; can’t hit with power, weak arm, cheats on the infield.” This led him to graduate school at Columbia and the University of Michigan, where he received his PhD in comparative literature. He has been at Tufts University since 1964, serving as provost for twenty-one years. Gittleman currently serves as the Alice and Nathan Gantcher University Professor. His “Reynolds, Raschi, and Lopat: New York’s Big Three and the Great Yankee Dynasty of 1949-53” was published in 2007. He has been a SABR member since 1986.

Sources

Frommer, Harvey, New York City Baseball: The Last Golden Age: 1947-1957. New York: Macmillan, 1980.

Gittleman, Sol, Reynolds, Raschi, and Lopat: New York’s Big Three and the Great Yankee Dynasty of 1949-1953. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2007.

Golenbock, Peter, Dynasty: The New York Yankees, 1949-1964. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1975,

Halberstam, David, Summer of ’49. New York: William Morrow, 1989.

Kahn, Roger, The Era: 1947-1957. New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1993.

Lanctot, Neil, Campy. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2011

Neft, David S., and Richard M. Cohen, Baseball, 14th edition, The Sports Encyclopedia Series. New York: St. Martin’s, 1994.

Rizzuto, Phil, with Tom Horton, The October Twelve. New York: Tom Doherty Associates, 1994.

Spatz, Lyle, Yankees Coming, Yankees Going. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2000.

Author interviews with Charlie Silvera, August 19, 2004; Bobby Brown, June 21, 2004; Sally Raschi, June 27, 2004.