1947 Yankees: The Yankees’ involvement with Leo Durocher’s suspension

This article was written by Jeffrey Marlett

This article was published in 1947 New York Yankees essays

Leo Durocher’s season-long suspension in 1947 resulted from several years of his riotous behavior. The pattern started during his playing days with the New York Yankees.

“For what?”

Such was Leo Durocher’s first response to the news on April 9, 1947, that Commissioner Albert “Happy” Chandler had suspended him from baseball for the 1947 season.[fn]Durocher, Leo with Ed Linn, Nice Guys Finish Last. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1975. p. 257.[/fn] The response was uncharacteristically short for The Lip, known throughout baseball for his verbal barbs. However, Commissioner Chandler had, upon pain of further suspension, requested silence from all parties involved in a series of clashes between the Brooklyn Dodgers and the New York Yankees. Chandler had fined both teams, fined a Dodgers assistant for the column he ghost-wrote for a Brooklyn paper in Durocher’s name, and had suspended Chuck Dressen, a Yankees coach, for thirty days. Leo’s suspension certainly appeared out of proportion.

Commissioner Kenesaw Landis had warned Leo about the damage his gambling friends could do, but Landis died in November 1944 and been replaced by Chandler. In October 1946 New York papers started associating Durocher again with a minor Hollywood actor, George Raft, who knew mobsters like Lucky Luciano and Owney Madden. Nationally syndicated columnist Westbrook Pegler led the charge with three columns indicting Durocher for his fast life and criminal associations. At Rickey’s request, Chandler summoned Durocher to discuss the matter, and Durocher duly apologized. Then, embodying Rickey’s statement that he could make any situation worse, Leo proceeded to tell the commissioner about his burgeoning love affair with actress Laraine Day, who was still married. The news stunned Chandler, but he did not threaten Durocher with suspension. The Brooklyn Catholic Youth Organization, though, had seen enough, and on March 1 withdrew its members from the Dodgers Knothole Gang.[fn]Mann, Arthur, Baseball Confidential: Secret History of the War Among Chandler, Durocher, MacPhail, and Rickey. New York: David McKay Company, 1951. pp. 43-47; Harold Parrott, The Lords of Baseball 2nd edition. Atlanta: Longstreet Press, 2001. p. 252. Lowenfish, Lee. Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007. p. 424.[/fn]

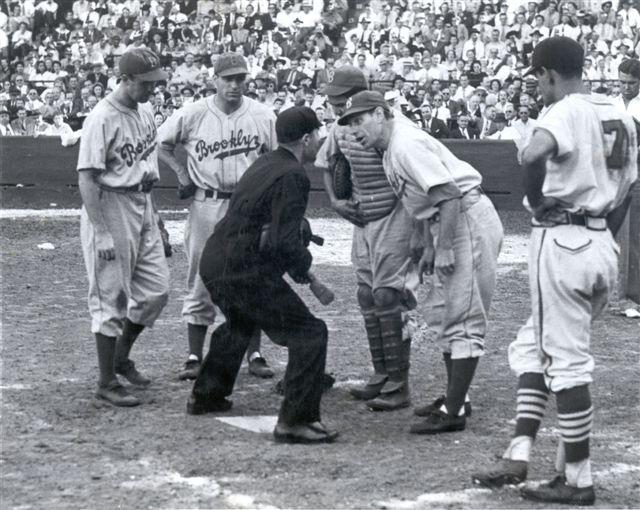

The events that actually caused Leo’s suspension came a week later. The Yankees, then owned partially by MacPhail, and the Dodgers were scheduled to play two spring-training games in Havana, Cuba. Just days before, Durocher had published a diatribe needling MacPhail (ghost-written by Dodgers staffer Harold Parrott) in the Brooklyn Eagle. On March 8 Durocher spotted nightclub owner Connie Immerman and racing handicapper Memphis Engelberg sitting near MacPhail. Both men counted among those Landis and Chandler had warned Durocher to avoid. Rickey publicly echoed Leo’s belief that a double standard existed: “one for Durocher and another for MacPhail.”[fn]Daley, Arthur, “The Lip Talked Too Much,” New York Times, April 11, 1947, p. 21; Durocher, Nice Guys Finish Last: 247-8.[/fn] The Yankees owner then declared that Rickey and Durocher had libeled him, and demanded that Chandler act.

Over the last two weeks of March Chandler organized two meetings: The first, on March 24 in Sarasota, Florida, featured all those involved—Durocher, Dressen, MacPhail, Rickey, his assistant Arthur Mann, and the Dodgers’ legal representative, Walter O’Malley. A second meeting, four days later in St. Petersburg, included MacPhail, Yankees assistant Arthur Patterson, Rickey, Mann, and O’Malley.

Chandler ran the proceedings, asking most of the questions. Durocher noted the “trial” bore little resemblance to constitutional freedoms. Patterson noticeably dodged Chandler’s question about the source of Engelberg and Immerman’s tickets. After the second meeting, Chandler casually asked Rickey, “How much would it hurt you folks to have your fellow out of baseball?” Rickey was astonished, but still thought the commissioner was bluffing. The Dodgers expected that Leo might receive a minor fine and perhaps a short suspension. The year-long suspension left them flabbergasted.[fn]Lowenfish, Branch Rickey: 425; Mann, Baseball Confidential: 100-21 (quoted 113). Durocher, Nice Guys Finish Last: 252-6.[/fn]

Two figures provide the connections between the Yankees and Durocher’s suspension: Charlie Dressen and Larry MacPhail. Both shared relationships and character traits with Durocher. In 1982 Red Barber wrote, “Try to untangle Durocher from either Rickey or MacPhail and it’s no story.”[fn]Barber, Red, 1947: When All Hell Broke Loose in Baseball. New York: Da Capo, 1982. p. 19. See also Eskenazi, Gerald, The Lip: A Biography of Leo Durocher. New York: William Morrow, 1993. pp. 199-200.[/fn] Barber could easily have added Dressen to the tangle of clashing personalities and jealousies. Like Durocher, Dressen was a diminutive, working-class Catholic. Both Dressen and Durocher enjoyed sporting pastimes like cards—especially bridge—and betting on horses. Consequently, both tended to manage their baseball teams with a healthy dose of hunch-playing and intuition. Finally, Dressen and Durocher knew each other quite well professionally. The two played together for two seasons in Cincinnati (1930 and 1931). They reunited in Brooklyn in 1939 when Durocher, in one of his first acts as Dodgers manager, named Dressen as one of his assistants.[fn]See Kahn, Roger, The Boys of Summer. New York: Perennial Classics, 2000. pp. 110-12 for Dressen’s background. Tygiel, Jules, Past Time: Baseball as History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.p. 163, for Dressen and Durocher’s shared managerial style.[/fn]

Nonetheless, Dressen initiated Yankee involvement in what would become Leo’s suspended season. In September 1946 he gave Rickey a verbal commitment to return to the Dodgers for the next season. Two months later he and another Dodgers coach, Red Corriden, joined the Yankees as coaches for new manager Bucky Harris. Rickey and Dressen did not get along well, largely because of Dressen’s gambling. Rickey even briefly fired Dressen as punishment in 1943, only to rehire him a few months later. Dressen tired of such lessons, and rejoined MacPhail. Dressen’s culpability led to his own thirty-day suspension.

But it was MacPhail who played a direct and, in the eyes of Brooklyn fans, malicious role in securing Durocher’s year-long suspension. MacPhail matched Durocher’s panache and dramatic flair. He was “the swashbuckling marauder, dressed to the nines in expensive but garishly loud suits . . . who thought his day was not complete unless he had done something worthy of mention in the press.” MacPhail had characteristically alienated three managers (Joe McCarthy, Bill Dickey, and Johnny Neun) in the 1946 season, so he needed a replacement. Rumors simmered that he even had approached Durocher during the season. In November he finally persuaded Bucky Harris, the former Washington Senators, Detroit Tigers, Boston Red Sox, and Philadelphia Phillies field boss, to take control.[fn]Warfield, Don, The Roaring Redhead: Larry MacPhail, Baseball’s Great Innovator. South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Communications, 1987.p. 68 (quoted), 180-81 (Harris), 169-70 (Chandler).[/fn]

MacPhail’s blustery entrepeneurship—familiar to fans of all the teams he’d owned—set the stage. Contacting Durocher midseason would have constituted tampering, a suspension-meriting offense. Brooklyn fans were certainly accustomed to Durocher-MacPhail spats, but these were almost always patched up within a day. Now MacPhail had gone too far. Public protests by the Yankees owner himself that he had not intended Leo’s suspension did not help. Making things worse was the widespread belief that Chandler owed MacPhail a favor for winning him the commissionership.[fn]Durocher, Nice Guys Finish Last: 259, 263.[/fn]

Consequently, Chandler’s own position in the Durocher maelstrom underwent intense scrutiny. A Brooklyn policeman mused that Chandler must have possessed special testimonial evidence, otherwise “how could he do such a thing?” A Brooklyn bartender exemplified the extent of the borough’s sense of injury: “We had bad teams until Durocher came along. Lippy put Brooklyn on the map all over the world and that’s no way to treat a man who does that.”[fn]Both quoted in Murray Schumach, “Tempers flare from Greenpoint to Canarsie by Ban on Durocher,” New York Times, April 10, 1947: 31.[/fn] New York Times columnist Arthur Daley argued that Chandler had reprimanded the wrong man. “The entire business was so childish as to be ridiculous. The unhappy Happy should have spanked them all and sent Rickey and MacPhail packing off to bed without their suppers.”[fn]Daley, Arthur, “Chandler Flexes His Muscles,” New York Times, April 10, 1947.[/fn]

Chandler had misgauged the combative atmosphere of New York’s sports and media culture. Pegler’s 1946 columns certainly stirred up controversy. Pegler had earned his muckraking credentials legitimately. He won the 1941 Pulitzer Prize for uncovering shady union practices, and in 1951 he was the first to name Bill “Mr. Big” McCormack as the crime boss controlling New Jersey’s shipping ports.[fn]Fisher, James T., On the Irish Waterfront: The Crusader, the Movie, and the Soul of the Port of New York. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2010. p. 174.[/fn] Nevertheless, within New York’s fevered sports and media climate, Pegler was but one, albeit widely read, voice. Years later, Durocher himself said “If a man dropped down from Mars and read nothing except Pegler’s columns for a month, he couldn’t help but believe the two great enemies of the Republic were Eleanor Roosevelt and Frank Sinatra.”[fn]Durocher, Nice Guys Finish Last: 242.[/fn] From Chandler’s perspective, though, Pegler’s work ignited the notion to remove Durocher.

Likewise, Chandler’s claimed communication with U.S. Supreme Court Justice Frank Murphy seems unfounded. During the two late March “trial” days, Chandler mentioned that “a big man” in Washington had read Pegler’s columns and then wrote to demand Durocher’s lifelong suspension. This turned out to be Murphy.[fn]Mann, Baseball Confidential: 114; Durocher, Nice Guys Finish Last: 262.[/fn] Two Brooklyn Catholic priests, Vincent J. Powell and Edward Lodge Curran, had spearheaded the Brooklyn CYO’s opposition to Durocher, so Murphy’s call for suspension did not portend well for Leo. Harold Parrott went so far as to blame Walter O’Malley, whose connections among Brooklyn’s Catholics could have stopped the witch hunt.[fn]Parrott, The Lords of Baseball: 253-54.[/fn]

However, the Catholic conspiracy theme seems dubious. Murphy’s most meticulous biographer does not focus on sports at all, even on an explosive character like Durocher.[fn]Fine, Sidney, Frank Murphy 3 vols., Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1975, 1979, 1984.[/fn] Furthermore, attempts to see collusion between Murphy and the Brooklyn diocese overlook Murphy’s own ambivalence towards his church’s clergy. While certainly devout, Murphy also exhibited an independent streak counter to the then-stereotypical “pray, pay, obey” image of Roman Catholics.[fn]Fine, Frank Murphy: The Washington Years, 1984: 10-12, 199-200.[/fn] Furthermore, presuming that Murphy did in fact contact Chandler, connecting the judge to Pegler in anything other than timing lacks evidence. Pegler and Murphy might have indeed both condemned Durocher’s behavior, but only Chandler melded their separate concerns into a singular moral argument. For his own part, Durocher claimed that Murphy soon distanced himself from Chandler’s claim.[fn]Durocher, Nice Guys Finish Last: 261-62. The only evidence Chandler actually possessed correspondence from Murphy himself appears in William Marshall’s Baseball’s Pivotal Era, 1945-1951, Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1999. p. 453, note 65.[/fn]

Almost immediately after the news of Durocher’s suspension broke, Red Smith of the New York Herald-Tribune wrote:

As baseball commissioner charged with administration of the national game, Chandler works for the people, the millions of baseball fans in the land. He does not, whatever his decisions may suggest and whatever his own opinion in the matter may be, work for Larry MacPhail.”[fn]Smith, Red, “Open a Window, Albert,” in Red Smith on Baseball. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2000. p. 33.[/fn]

Chandler’s demand for absolute silence from the event’s participants provided the stigmatization necessary to fuel conspiratorial thinking. In Smith’s column the MacPhail-Chandler relationship provided the real reason for Durocher’s suspension, not Chandler’s official conclusions. Chandler refusal to publicize his evidence indicated fear and possibly even guilt, argued Smith. Baseball fans deserved better, he said. “They have a right to study the evidence which convinced Chandler that Durocher was guilty and MacPhail innocent of conduct detrimental to baseball. The Brooklyn club, as defendant in the case, has a right to have that evidence made public.”[fn]Ibid., 34.[/fn]

Arthur Daley agreed: “If the Flatbush Faithful mutter bitterly today ‘We wuz robbed,’ their grief is understandable.”[fn]Daley, Arthur, “Chandler Flexes His Muscles,” New York Times, April 10, 1947.[/fn] Some Brooklyn fans even burned Chandler in effigy.

The sentiment did not die quickly. In late April, before celebrating Babe Ruth Day, Chandler had to stare down an initially hostile crowd at Yankee Stadium. Sportswriters in other Major League cities, while not Durocher fans, argued that the punishment was went too far.[fn]Marshall, Baseball’s Pivotal Era, 1945-1951: 115 (effigy and sportswriters), 116 (Yankee Stadium)[/fn] Fifteen years after the suspension, columnists still accepted Chandler’s guilt in the matter. Writing from Los Angeles, Jim Murray reminisced that Durocher got set down one whole year just for standing next to a gambler. Baseball paid him off on the q.t. because the action was as illegal as lynching and everyone knew it but the commissioner, Happy Chandler, who had read one too many chapters of the life of Judge Landis.[fn]Murray, Jim, “Whose Deal?” Los Angeles Times, September 9, 1964, 1, 7.[/fn]

However, other interpretations have detected conspiracy behind Durocher’s suspension from the increasingly bitter relationship between Rickey and MacPhail. Peter Golenbock dates the conflict to spring training 1939 when Durocher started Pete Reiser, then a Minor Leaguer whom MacPhail had agreed to “hide” as a favor for Rickey (an offense worthy of suspension itself), when Rickey was still running the Cardinals. Rickey accused MacPhail of reneging on their secret deal and, in 1942, felt MacPhail had ruined Reiser’s once-promising career.[fn]Golenbock, Peter. Bums: An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers. New York: Contemporary Books, 2000. pp. 25-26, 55-61.[/fn]

Geography and demographics also contributed to conspiratorial thinking behind Durocher’s suspension. Within New York’s five boroughs, Brooklyn stood as rough-hewn also-ran. A strident anti-triumphalism thus quickly emerged among the borough and its team’s fans. In 1947 MacPhail, who had created Durocher’s pennant-winner in 1941, now stood victorious on the other side. Along the way he had swiped away Dressen. Durocher’s suspension seemed the pinnacle of MacPhail’s perfidies—all committed with the hated crosstown rival Yankees. Rickey was so distraught by the loss that, when confronted by a jubilant MacPhail after Game Seven, he broke all ties, severing a professional relationship that dated to 1930. MacPhail then went famously on a drunken binge wherein he retired from baseball, fired Yankees executive George Weiss, and scuffled with his fellow team owners.[fn]Kahn, Roger, The Era 1947-1957: When the Yankees, the Giants, and the Dodgers Ruled the World. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002. pp. 141-43.[/fn]

Forty years later Durocher still harbored animosity, refusing even to speak Chandler’s name when interviewed. Durocher indicated that while he maintained his silence publicly, he repeatedly chewed off Chandler’s ears over the telephone. In Leo’s view his suspension’s cause, if it had any at all, rested solely with the commissioner.[fn]Vecsey, George, “Sports of The Times; The Lion Roars A Little.” New York Times, May 24, 1987. Durocher, Nice Guys Finish Last, pp. 263-68.[/fn]

As Leo himself said of MacPhail, “He did things, and when you do things, other things, unexpected things, are always happening around you.”[fn]Durocher, Nice Guys Finish Last, 119.[/fn] Something was bound to happen, and it did. But Durocher and MacPhail had accepted each other’s apologies in the March 24, 1947, meeting, so in their minds the matter was settled. The unexpected thing, Leo’s suspension, came from Chandler, whose appointment MacPhail orchestrated.

Most figures involved suspected Durocher would return to baseball, which he certainly did. Harold Parrott asserted that the manager “led a charmed life, walking the tightrope across problems with women, money, umpires, and Unhappy Chandler.”[fn]Parrott, The Lords of Baseball, 196.[/fn]

JEFFREY MARLETT teaches religious studies at The College of Saint Rose in Albany, New York. He is the author of “Saving the Heartland: Catholic Missionaries in Rural America, 1920-1960” (Northern Illinois University Press, 2002). He became interested in Leo Durocher while preparing undergraduate ethics courses.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Freddy Berowski, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York; Joe Emmick, Patrick Hayes, and Lyle Spatz.