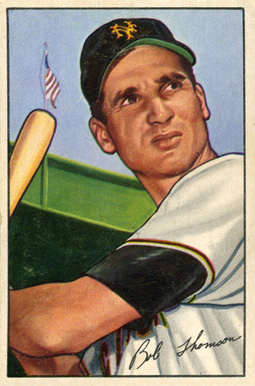

1951 Giants: Fortune smiled on Bobby Thomson’s lucky glove

This article was written by Joe Phillips

This article was published in 1951 New York Giants essays

Bobby Thomson’s home run in the bottom of the ninth in the third game of the 1951 National League playoff is generally considered baseball’s greatest walk-off home run.

Bobby Thomson’s home run in the bottom of the ninth in the third game of the 1951 National League playoff is generally considered baseball’s greatest walk-off home run.

Broadcaster Russ Hodges captured Thomson’s shot and froze it in time, echoing it through baseball’s ages. After the ball soared over Dodgers outfielder Andy Pafko’s forlorn face, the ecstatic Thomson bounded around the bases, past his manager and third-base coach Leo Durocher to his winning, pennant-clinching run. The Giants had come out of a seemingly bottomless hole to victory.

When Thomson rounded third base, likely no one in the 30,000-plus crowd paid any notice to Durocher. Perhaps no one except the newsreel camera. With Thomson jogging to the plate, the joyful, leaping Durocher suddenly stopped, turned around, and picked up the glove Thomson had left near the third-base coaching box as he left the field the previous half-inning.

Seconds later the Giants’ Eddie Stanky would jump atop Leo, who was still carrying Thomson’s glove. All would head toward the mass celebration.

What was Thomson’s glove doing at third base? This was still the day when ballplayers customarily left their gloves on the field between half-innings. Thomson had been playing third base and dropped his glove near there to return to the dugout for his team’s last at-bat.1

Fortune must have smiled on Thomson, Durocher, and the glove. Maybe it was due to Durocher. The Giants manager was an ardent believer in luck and lucky charms. Before the first at-bat and when assuming his coaching position at third base, Leo performed a good-luck ritual. He would work his hand into and pound the glove left behind by this third baseman near his coach’s box. Thomson’s dropped glove that inning had to be luckiest glove Durocher ever pounded.

Were baseball gloves considered lucky? Many a defensive player might agree with that assessment when his glove saved an out or cut off a rally.

And manager Durocher might have been familiar with perhaps the most famous of lucky gloves. That belonged to his former teammate with the New York Yankees in the 1920s, Babe Ruth. Ruth, in fact, dubbed the peppery Yankee rookie shortstop “the automatic out.”

Lucky glove? It was Babe’s own Draper & Maynard G41 model. He used this glove in his last years with the Boston Red Sox and in his first seasons with the Yankees. Ruth even coined the “lucky” tag for his soft, gray-toned glove. The Bambino had declared his Draper & Maynard glove and those like it to be the “lucky dog kind.” The company logo was a bird dog owned by one of the owners and it was stamped into each D&M glove.2

The Dog Logo had emerged from a meeting attended by the two owners, Jason Draper and John Maynard. Maynard’s bird dog, Nick, wandered into the room and someone exclaimed: “There’s our trademark.” It stuck, and soon the dog emblem was used throughout the company’s advertising and promotions.

Ruth would put the “Lucky Dog” meaning into the D&M advertising and literature later when one day he spotted a rookie Red Sox outfielder coming on to the field with a D&M glove and Babe yelled, “So you’ve got one of the lucky dog gloves?” That remark, coming from the game’s most famous player, soon caught the attention of the company, which began using the phrase in its advertising.3

Still, it’s hard to deny that Thomson’s 35-inch Adirondack bat had stolen the equipment show that October playoff day, capping the Giants’ unbelievable, almost mythical rise from 13 games back to overtake the Dodgers that day for the pennant.4

Baseball is a game whose playing gear consists largely of leather and wood. Although Thomson’s Adirondack wood stick won the day, plenty of prime cowhide leather was available for the skilled Giants defenders’ hands. They were a fast, quick, and alert defensive unit. Monte Irvin and Willie Mays were of Gold Glove caliber in 1951, several years before that award was established in 1957. Center fielder Mays took home many Gold Gloves after the prize was created. Other Giants – Thomson, Al Dark, Stanky, Whitey Lockman, Hank Thompson, and Wes Westrum – were all considered better than average defenders at their positions. And they were versatile. First baseman Lockman was a former outfielder. Thomson was adept at third and the outfield as was one the game’s earliest black players, Henry “Hank” Thompson, who could play third base and the corner outfield spots.

The irascible Stanky was a noted glove prankster. One of his best tricks was that of hiding opponents’ gloves.

Thomson himself had once been a victim of Stanky’s glove antics. When he was a Giants rookie playing second base, Stanky, his opposite number at second for the Dodgers, made his glove disappear. Between innings Stanky kicked Thomson’s glove from near second base, where it had been left on the field, to the outfield bullpen area. Thomson spent puzzled minutes looking for his missing glove. Bill Rigney, another Giants keystoner of the period, once complained that Stanky buried his glove under second base during a game.5

The 1951 Giants used a mixture of models, but likely most were Rawlings, the preferred brand of its day. Rawlings had built a massive reputation among major-league players in the preceding 20 years. The company had a stroke of luck in the early 1920s. St. Louis Cardinals pitcher Bill Doak strolled into the company’s St. Louis plant one day and demonstrated a novel idea to the company: a glove that would form a natural pocket and be more flexible. Doak’s idea was to raise the glove’s thumb to form a deeper pocket, and to provide a laced leather web that eliminated the stiffness of the older style sewn web. Rawlings introduced the Bill Doak model to major leaguers shortly afterwards. It had an immediate positive impact on defensive play and arguably countered the effect of the lively ball era to some degree. Orders came pouring in. The Bill Doak glove would stay in the Rawlings line for 30 years, with other glove manufacturers soon following suit with similar styled models.6

By the 1950s the vast majority of major leaguers were wearing Rawlings gloves. Only a sprinkling of Wilson, MacGregor, and Spalding gloves dotted the defensive landscape. In fact, Rawlings’s annual player surveys showed that 70 to 80 percent of players wore Rawlings gloves during the 1950s. Rawlings had not only captured most of the fielders’ glove use market the leagues, but its popular “Trapper” first baseman’s mitt had a stranglehold in popularity at that position from the late 1930s through 1950s.7

While most players used Rawlings gloves, it didn’t mean they had contract endorsements with the St. Louis manufacturer. Many major leaguers had signed glove endorsement contracts with other companies and typically received two free gloves and a couple of pairs of baseball shoes for their endorsement. Loyalty went only so far on the field, though.

Thomson, for instance, had become a staunch MacGregor glove endorser and user. But some Giants like Dark and Sal Maglie, though they might showcase Spalding gloves in that company’s advertising, wore Rawlings leather on the field. Others, including Stanky, Hank Thompson, Irvin, and Westrum (who wore a Wilson Mancuso mitt) endorsed lesser-known brands like the Denkert Company, which produced youth models and private-label gloves. In fact Denkert’s Hank Thompson retail glove became one of the most popular youth gloves in the country.

Several Wilson glove endorsers from other teams, like Gold Glovers Gil Hodges and Roy McMillan, preferred Rawlings gloves on the field. McMillan stayed with his Rawlings glove until Wilson came up with its revolutionary A2000 model in 1957, then he switched. Daryl Spencer, who joined the Giants in 1952, said that “I used several different models during my early career. I signed with MacGregor while still in the minors, but never did use the model they designed for me.”8

Future Hall of Famer Robin Roberts was also a MacGregor endorser but a Rawlings user. He once caught a good deal of flak from MacGregor when he appeared on the cover of a national sports publication with his Rawlings glove clearly identifiable.

The glove companies were faced as well with the issue of signing black stars to endorsement contracts and placing their names on retail model gloves. Jackie Robinson, for instance, signed a contract with the Dubow glove company of Chicago, but few seem to have been distributed judged by their rarity today. Post-career Robinson “autograph” gloves would appear in the 1960s under the Caprico exported brand.9

MacGregor, based in Cincinnati, was the most active in signing black players and using their names on its store-sale gloves. Its endorsers included outfielders Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, and Frank Robinson. Wilson later signed Roy Campanella and Ernie Banks, but the practice of signing black players as endorsers didn’t begin until the mid-1950s. St. Louis-based Rawlings was last, finally placing Yankees catcher Elston Howard’s name on its catchers mitts in 1960.

Yankees stars largely endorsed Spalding, a practice begun by Babe Ruth after he switched his endorsement from D&M to Spalding in the late 1920s. Joe DiMaggio, Bill Dickey, Phil Rizzuto, and Yogi Berra all followed.

With the growth of TV, glove endorsement contracts became quite lucrative by the 1990s, and the players who signed had to be careful to match their wearing brand with their endorsement. In recent years, some pitchers, for instance, have sewn or glued their endorsed brand over that of the glove brand that they actually use, wary of television cameras zooming.

The glove that Willie Mays used to make his historic catch of a Vic Wertz drive in the 1954 World Series is in the Baseball Hall of Fame. Rumor has it that Thomson’s glove from the 1951 series is also at Cooperstown.

At least according to Leo Durocher, that’s the lucky one.

JOE PHILLIPS is a former sports editor and semipro baseball player who has been a Cincinnati Reds fan since the late 1940s. One of his devotions has been to vintage baseball gloves. On that subject he has written a book, “Nokona Ball Gloves — A Texas Tradition,” a history on the Nokona ball glove company. Phillips serves as an appraiser of baseball gloves and has produced various guides and articles to help collectors in this hobby. He has been featured in “Sports Illustrated” and has served a columnist for several sports memorabilia publications.

Notes

1 Jay Feldman, “Of Mice and Mitts, and of a Rule That Helped to Clean Up Baseball,” Sports Illustrated, February 20, 1984.

2 Erma T. Ahern, “History of Draper-Maynard Company, Plymouth, N.H.,” Plymouth State College Paper 1. 18; Draper & Maynard Catalog 1926, 19 (both on file with author).

3 Louise Samaha McCormack, “The History of the Draper & Maynard Factory in Plymouth, The Weirs (New Hampshire) Times, October 11, 2011, 18.

4 In the course of a doubleheader on August 11, the Giants were briefly 13½ games behind the Dodgers.

5 Joe Phillips, “Stanky Hides Thomson Glove,” The Glove Collector Newsletter, November/December 2002, 5.

6 Noah Liberman, “Born in Shame, The First Glove,” in Glove Affairs, 11-13; Bill Doak, “A History of the Bill Doak Glove,” in Rawlings Sporting Goods Pamphlet, 18-19; “Be a Sports Equipment Expert,” Rawlings Equipment Article No.1, 1950, 6.

7 Bob Duppstadt, “All Rawlings Trappers Are Not the Same,” The Glove Collector Newsletter, January 2000, 1, 5.

8 Joe Phillips, “First Glove a ‘Mort Cooper’ for Shortstop Gold Glover McMillan,” The Glove Collector Newsletter, July/August 1992, 2; Daryl Spencer letter to author, April 6, 2002 (on file with author).

9 Carmi Brandis, “List of Players Who Broke the Color Barrier,” Sports Collectors Digest, March 5, 1993, 158-160.