1966: The Dodgers Return to Japan

This article was written by Andy McCue

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1960-2019

Maury Wills attempts to turn a double play against the Yomiuri Giants (Robert Fitts Collection)

By 1966, the bloom was coming off the chrysanthemum of Japan tours by major-league teams. Rebuilding US-Japan relations was less worrisome as the Japanese economy surged and Tokyo proved a stout ally for American fears about Russian and Chinese policies in Asia. Concerns about whether the tour would make money thrust themselves into the picture. The strain of major-league pennant races made more players reluctant to travel, and the lure of “exotic” Japan had dimmed.

The changes showed up between the lines for the first time as an American team barely outlasted its Japanese rivals. Still, the 1966 tour provided the venue to regularize the official relationship between American and Japanese professional baseball.

It had been a decade since the last Dodgers’ tour of Japan. That had been a Brooklyn Dodgers team that had just dropped a seven-game World Series to the New York Yankees after defeating them the previous year. This time it was a Los Angeles Dodgers team, which had just been swept in the World Series by the Baltimore Orioles a year after winning it all. The hoped-for match between the American and Japanese champions, a consistent hope of the Tokyo promoters, was thwarted yet again.

The tour followed in the wake of a contentious battle between the San Francisco Giants and the Japanese Pacific League’s Nankai Hawks over pitcher Masanori Murakami. Murakami, whom Nankai lent to the Giants for American-style training, proved such a sensation that the Giants called him up late in the 1964 season. He pitched so well that they refused to return him to Nankai and kept him for the 1965 season. The Japanese team thought the two clubs had a gentleman’s agreement, the Giants thought they had a binding contract for Murakami’s services. After much negotiation and bitterness, he had returned to Nankai for 1966.1

The bad feelings over Murakami hovered in June 1965 as the Yomiuri Shimbun withdrew its offer to sponsor a tour that fall by the Pittsburgh Pirates. For the Japanese newspaper, sponsoring a tour was a commercial venture and “[t]he Pirates are unknown in Japan and we did not want to risk going into the red,” said Kanzo Hashimoto, head of the company’s promotions department.2

Commissioner Ford Frick was holding to the contract he had worked out with the Japanese in 1955. Under that agreement, a major-league team could visit every two years, with the selection alternating between the National and American Leagues. The Pirates had been the first team to volunteer for the 1965 trip, Frick said, so they were chosen. The last team to visit Japan had been the Detroit Tigers in 1962, and the 1964 trip had been postponed because Tokyo was hosting the summer Olympics that year.

Yomiuri, which also owned the Yomiuri Giants, Japanese professional baseball’s dominant team, turned to the Dodgers. Walter O’Malley had been steadily building a relationship with Japanese professional baseball in the years since his team’s 1956 visit. Japanese players and coaches had been hosted at spring training in Vero Beach as well as in Los Angeles. Dodger instructors, including Al Campanis and Tommy Lasorda, had made spring-training visits to conduct clinics in Japan.3 The newspaper executives knew the Dodgers would be a strong draw.

Frick was annoyed at Yomiuri’s end run to the Dodgers and The Sporting News editorialized that it would not work.4 But by the spring of 1966, O’Malley and Toru Shoriki, president of the Yomiuri Group and its Giants, were negotiating terms for the trip.5 In a little over a month, the formal invitation was announced.6 A few weeks later, baseball owners approved the tour, rubber-stamping Yomiuri’s end run.7 Both the Dodgers and Shoriki’s Giants had been champions in 1965, and the matchup offered promising opportunities for promotion and to see how much Japanese professional baseball was progressing.

Clouds appeared on the tour’s horizon even before the formal invitation. Dodgers shortstop Maury Wills, the prime offensive engine of a team that did not score well, was planning a career as an entertainer when his baseball career ended. The 33-year-old had permission to arrive a week late at 1965 spring training while he toured Japan playing his banjo and singing. But, general manager Buzzie Bavasi claimed he had revoked that permission during salary negotiations.8 Hard things were said on both sides before an agreement was reached for a $35,000 raise to $80,000 for 1966.9

Wills’s negotiations were overshadowed that spring by the revolutionary holdout of Dodgers aces Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale. Drysdale’s appreciation of his value had been sparked by an offer from Japan of a $500,000 multiyear pact in late 1965.10 Frick threatened both Drysdale and the Japanese for a move he said would break Drysdale’s contract and jeopardize both the pitcher’s future and Japanese baseball’s relationship with the major leagues.11 The offer’s detail and whether it was real were never revealed as Drysdale chose to try to increase his salary and stay in the United States.

In two innovations anathema to baseball owners, and especially Walter O’Malley, Drysdale and Koufax held out together and hired an agent. They asked for three years, with $200,000 annually for Koufax and $150,000 for Drysdale.12 Drysdale had earned a reported $75,000 in 1965, with Koufax slightly less.13 At first, Bavasi and O’Malley scoffed. But the hurlers hired an entertainment industry agent and began to work on deals for their own Japan tour and for movie studio and television contracts.14 The first movie opportunity fizzled, but Drysdale and Koufax ultimately appeared as actors. The leverage had its effect. Eventually, Koufax signed for $125,000 and Drysdale for $110,000.15

But the ripples went further. New Major League Baseball Players Association Executive Director Marvin Miller watched the holdout closely and pointed to the inequities of the process and the value of agents as he educated the board of the Players Association to the problems and the opportunities of negotiations.16 Within the Dodger organization, it gave Koufax and Drysdale much more freedom from management dictates. They would use that power to decline to accompany the team to Japan that fall.

As the season progressed, there were increasing signs that other Dodgers were not enamored of the trip. The 1966 season was a grueling pennant race. The 1965 World Series winners led the league for only one day before gaining first place permanently on September 11. Their lead was never bigger than 3½ games. The season came to a close in a rain-splattered East Coast trip that included multiple doubleheaders. The Pittsburgh Pirates were not out of it until they lost the second game of a twin bill on October 1. The San Francisco Giants were eliminated only when Koufax won the second game of the Dodgers’ doubleheader in Philadelphia on October 2, the last day of the season. “Thank God it’s over,” said Koufax, echoing the sentiments of his teammates.17

The team’s exhaustion was clearly exhibited in the four-game World Series sweep at the hands of the Baltimore Orioles. The Dodgers’ offense managed only four runs in the four games.

All this played into existing disenchantment with the Japan trip. As early as June, Phil Collier of the San Diego Union was reporting that Koufax, Drysdale, catcher John Roseboro, and outfielder Ron Fairly, the team’s player representative, were balking. “All we know is what we’ve read in the newspaper. The club hasn’t told us a thing,” Fairly told Collier. O’Malley had done all the negotiations with Shoriki without consulting the players.18 By August, Maury Wills’s name was added to the reluctants’ list.19

The front office brought pressure and most players fell into line. Ron Fairly said it was made clear to him that he would have to go. Wills tried to beg off with a sore knee. He’d twisted it beating out a bunt in July but had played on what was feared to be torn cartilage for the rest of the season. On the day he twisted his knee, he had 30 stolen bases. He would steal only eight the remainder of the season and had to be hypnotized to be willing to endure the pain from the knee and the raw patches on his legs from sliding. He too was told he had to go, but was promised he would play minimal amounts. Wes Parker told Walter O’Malley he had been to Japan before and wasn’t interested in seeing it again. Besides, he was sore and tired after the season. Parker was allowed to join Koufax and Drysdale with the stay-at-homes. Don Sutton, who had arm trouble surface in September, was held back on medical advice.20

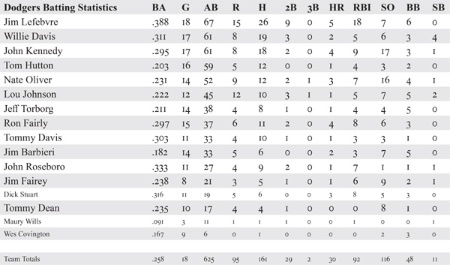

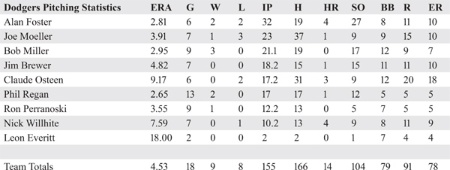

The pitching situation was a severe blow as the Dodgers left California. Koufax, Drysdale, Claude Osteen, and Sutton had started 154 of the team’s 162 games. Only Osteen was on the trip, and manager Walter Alston suggested he was tired as well.21 Pitching had carried them to the pennant, giving up three runs a game, more than a run lower than the league average. Meanwhile, the offense was scoring 3.7 runs a game, third worst in the league. The Dodgers would face Japanese teams with the same anemic offense but a heavy sprinkling of arms from the bullpen and their minor-league system.

The players who did go each received $3,000 and the equivalent of another $750 in yen from Yomiuri. The players talked of buying cameras and other electronics.

The team left on the trip under a cloud of skepticism in the wake of the World Series. Typical was the Los Angeles Times’s Frank Finch’s story previewing the trip: “Having endeared themselves forevermore in the hearts of Marylanders with their peaceful visit to Baltimore last weekend, the Dodgers depart today for a goodwill tour of Japan.”22 Snide references to the World Series would populate headlines and stories throughout the trip.

The team stopped in Honolulu for two exhibition games against teams of local major and minor leaguers with Bo Belinsky and Don Larsen brought in to provide the pitching. The Dodgers won both handily.23

While with the Dodger party in Honolulu, Commissioner William Eckert discussed a deal with his Japanese counterpart, Toshiyoshi Miyazawa, to cover future trips to Japan and, he hoped, avoid the disagreements that had clouded the Pirates’ proposed visit and the Dodgers’ eventual trip. They tentatively agreed that no team could visit Japan more than once in a six-year period and “no two teams from the same league can visit Japan more than two years in succession.”24

In Japan, expectations were high. “United States-Japan Battle of Champions” headlined the Yomiuri newspaper amid talk of a “real World Series.”25 The American military’s Far East Network announced it would broadcast most of the games.26 The 80-person Dodger delegation arrived in Tokyo on October 20 to the expected lavish greeting and a full slate of social events as well as ballgames. O’Malley blamed Koufax’s absence on a sore arm and said Drysdale had to attend to “business interests.” Asked by reporters if he foresaw a Japan-US International Series, O’Malley said, “I don’t see how you can prevent it. Japanese baseball is progressing admirably and the ballplayers are skillful. The public will demand it.”27 And, asked if the Dodgers would make a special effort to beat the Japanese champion Yomiuri Giants, O’Malley said, “definitely so.”28 Added Alston, “We’re on a four-game losing streak and want to win here.”29

The next day, Eckert presented Shoriki with a bronze plaque bearing an engraved message and signature from President Lyndon Johnson. After handing the message to Shoriki, Eckert also presented him with a World Series championship ring. It was the first World Series ring ever presented to a person not connected with a team participating in a World Series. “I myself and other Japanese concerned would like to further continue to promote Japan-U.S. friendly ties and contribution to peace, through baseball,” Shoriki said.30 The Dodgers worked out at Tokyo’s Korakuen Stadium in anticipation of the next day’s opener.

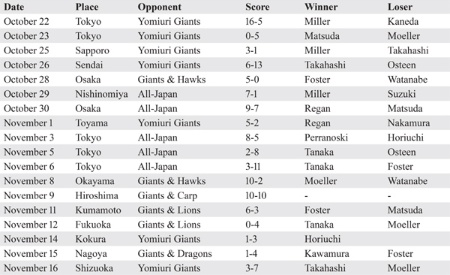

Game 1: October 22, Tokyo

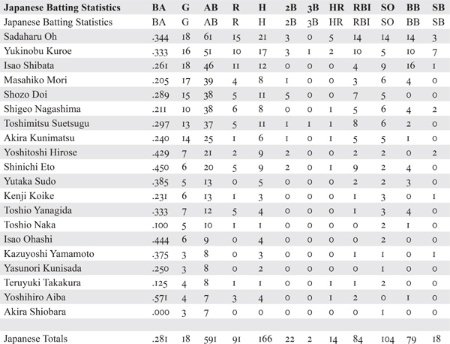

The Dodgers started the tour with a bang, 21 hits including six homers in a 16-5 drubbing of the Yomiuri Giants. Willie Davis and Jim Lefebvre hit two homers apiece while Tommy Hutton and Osteen each hit one before 40,000 people at Korakuen. Yomiuri provided a 7,000 yen ($19.44 in those days) reward for each home run.31 The game story noted that the 21 hits were four more than the Dodgers had managed in the entire World Series.32 Outfielders Toshimitsu Suetsugu and Akira Kunimatsu each had two hits to lead the Giants. The Giants had wrapped up a Japan Series championship over the Nankai Hawks on Wednesday October 19, while the Dodgers had not played a serious game since October 9.

Game 2: October 23, Tokyo

The Giants evened up the series as left-hander Akio Masuda shut out the visitors, 5-0, allowing just three singles. Another crowd of 40,000 saw Suetsugu provide the key hit with a triple. “We were just no good today,” said Alston. “The boys just couldn’t touch the Japanese southpaw. He had a sneaky fastball plus a good assortment of other pitches.”33

The defeat echoed loudly in the United States the following Saturday (October 29). ABC had sent Red Barber to Tokyo for its weekly Wide World of Sports. The segment reported on the Dodgers’ tour and focused on Masuda’s gem. He “made the Dodgers look like sleepwalkers, groping blindly and mechanically on the road to nowhere,” wrote Arthur Daley in the New York Times.34

Game 3: October 25, Sapporo

The Dodgers returned to the victory column with a 3-1 win over the Giants at Maruyama Stadium in Japan’s northernmost major city. Despite a steady rain, a crowd of 30,000 watched left-hander Kazumi Takahashi, who was chosen to start because of his similarity to Masuda, give up run-scoring hits to Maury Wills, Lou Johnson, and Willie Davis. Davis’s RBI was aided by Sadaharu Oh’s error. Katsutoyo Yoshida drove in the Giants’ run.35 In an incident that would echo for several years, Wills sprained his injured knee rounding third base when a rain-soaked patch of grass gave way. He was immediately replaced by pinch-runner Tommy Dean.

Game 4: October 26, Sendai

The Giants evened up the series yet again, mowing down the Dodgers 13-6 at Miyagi Stadium before 32,000 fans. The 13 runs set a record for the most tallies by a Japanese team against an American professional club. Jim Barbieri gave the Dodgers an optimistic start with a leadoff home run, but Yukinobu Kuroe matched him in the bottom of the first. The Dodgers’ second featured four runs on a parade of singles, but it was the bottom of the second that proved decisive. The Giants pounded Osteen and young Joe Moeller for six runs on five hits and two walks with two outs. Dodger minor leaguer Leon Everitt gave up another four runs in the seventh inning.

October 27 was a travel day and the Dodgers stopped in Tokyo on their way to Osaka. While there, Wills asked Walter O’Malley’s permission to return to the United States for medical treatment on his knee. O’Malley, already missing Koufax and Drysdale, refused. Wills said he had been promised he would only have to play a couple of innings a game but had played almost full games early in the series. He decided he needed to go and jumped on a flight to the United States.

O’Malley was incensed. “As the captain of the team, a higher degree of devotion to duty was expected of Maury,” the owner said. Then, adding a subtle threat about Wills’s post-playing future, O’Malley added: “I thought this particular boy showed evidence of having executive ability, and so did others.”36 The Wills story would come to dominate US coverage of the trip.

Game 5: October 28, Osaka

After a travel day, the Dodgers faced off with a team of players chosen from the Giants and the Nankai Hawks, champions of Japan’s Pacific League. (The Giants were champions of the rival Central League.) Alan Foster, who had spent the 1966 season with the Dodgers’ Albuquerque farm club, shut out the Japanese team 5-0 in front of 19,000 fans at Osaka Stadium. Utility infielder John Kennedy contributed two home runs. (He had hit three during the regular season.) The game featured the Dodgers’ first meeting with Murakami in Japan. In his two years in the National League, Murakami had pitched 13 innings against the Dodgers, giving up only one earned run. For Nankai in 1966, Murakami had gone 6-4 with a 3.08 ERA. That day in Osaka, he gave up three runs in 1⅔ innings, including one of Kennedy’s blasts and another by Barbieri.

Game 6: October 29, Nishinomiya

The Dodgers’ bats livened up in a second game against an all-star squad, winning 7-1 in this Osaka suburb. Jim Brewer, Bob Miller, and Phil Regan stifled the Japanese team, while Lou Johnson and Tommy Davis contributed their first home runs of the tour. The crowd of 30,000 at Nishinomiya Stadium saw the Dodgers frustrate the All-Stars by turning four double plays.

Game 7: October 30, Osaka

The Dodgers got a measure of revenge against Masuda, their nemesis in the second game, as Dick Stuart and Nate Oliver reached him for home runs to key a five-run ninth inning and a 9-7 Dodgers victory at historic Koshien Stadium, home to Japan’s annual high-school tournament. Murakami started the game and pitched 3⅓ shutout innings, but the bullpen could not hold the lead.37 The All-Stars had taken the lead by beating up on Joe Moeller and Ron Perranoski for four runs in the seventh inning. Phil Regan and Nick Willhite restored order and shut out the Japanese team for the rest of the day. John Kennedy also homered for the Dodgers, while Teruyuki Takakura of the Nishitetsu Lions hit one for the All-Stars before 43,000 people.

Game 8: November 1, Toyama

The Giants rejoined the campaign in this seaside resort city and the Dodgers prevailed with a 5-2 victory. The score was tied 2-2 in the top of the eighth inning. Akio Masuda was brought in yet again, but pinch-hitter Dick Stuart drove in a run and Al Ferrara singled to drive in two more. Phil Regan shut down the Giants in the eighth and ninth for the win at Toyama Stadium before 23,000 fans.

November 2 was a travel day and the Wills story was thickening. In Tokyo, an “embarrassed” O’Malley said he would be meeting Japanese Prime Minister Eisaku Sato on Friday and “try to explain and apologize for Wills.” O’Malley sought to frame it as a larger issue: “The United States is more or less involved in this loss of face caused by Wills’ defection.” O’Malley felt his long commitment to developing baseball as an international sport and building close ties with Japanese baseball was being undermined by Wills. The US government had not officially sponsored the trip but President Lyndon Johnson had sent a message of encouragement to the team.38

Wills, meanwhile, was proving elusive. He had gotten off his US-bound flight at a refueling stop in Honolulu. The Dodgers’ team physician, Dr. Robert Kerlan, said he had not heard from Wills. The shortstop/musician was soon spotted playing his banjo with Don Ho at Duke’s, a Honolulu night club, and at other spots around the city.39

In Japan, four groups of Dodgers visited four US military hospitals in the Tokyo area.40 The cultural and social obligations of the tour demanded time nearly every day with receptions, cocktail parties, golf outings, visits to tourist sites, and other diversions taking up the Dodgers’ between-games time. It was not a restful vacation.

Game 9: November 3, Tokyo

It was a Dodger homer barrage in an 8-5 victory over the Japan All-Stars as a crowd of 39,000 celebrated the Culture Day holiday at Korakuen Stadium. Ron Fairly hit bases-empty and three-run homers while Jeff Torborg and Jim Lefebvre slugged two-run shots. It would prove the high point of the trip, with the Americans now 7-2.

Game 10: November 5, Tokyo

After a day to reflect, the Japan All-Stars regrouped for an 8-2 win before 34,000 at Korakuen Stadium. Shinichi Eto of the Chunichi Dragons started the parade with a two-run homer in the first. The Giants’ Sadaharu Oh, who had led the Central League with 48 homers, contributed two more round-trippers. Jim Lefebvre’s bases-empty homer was the only protest by the Dodgers. “Too much Eto and too much Oh,” said Alston. “The barnstorming major leaguers never looked more listless,” wrote Pacific Stars and Stripes sports editor Lee Kavetski.41

Game 11: November 6, Tokyo

The next day the Dodgers played at Korakuen Stadium before 34,000 people including Emperor Hirohito and Empress Nagako. The team was not up to royal scrutiny, losing 11-3 to the Japan All-Stars. Alan Foster’s first pitch was deposited in the left-field stands by the Giants’ Shigeo Nagashima. Yukinobu Kuroe of the Giants and pitcher Tetsuya Yoneda of the Hankyu Braves also homered. Ron Fairly and John Roseboro homered for the Dodgers. After the game, the Dodgers emerged from their dugout to tip their caps and wave to the royal couple, who had never seen a visiting American team before and had not been to a Japanese professional league game since 1959.42

Eckert and O’Malley made their visit to Prime Minister Sato. During a five-minute meeting at Sato’s official residence, the Americans presented a baseball with O’Malley’s signature and a pass good for all major-league games for the 1967 season. They also presented O’Malley’s apologies for Wills’s absence.43

“The Dodgers may have drawn blanks elsewhere, but they are diplomatic successes in Japan,” reported the Los Angeles Times’s Frank Finch. “No matter where they go, to a shrine, a restaurant or a ball park, they are besieged by the friendly grins of red-hot baseball fans. The official badge issued by Walter O’Malley to the touring troupe is like an open sesame. People who can’t read English instantly recognize the familiar ‘Dodgers’ name in its script form. ‘Doh-jars,’ with the accent on the second syllable, is one of the most popular words in Tokyo, Sapporo, Osaka, Sendai, Nagoya and other cities where the team has appeared.”44

Wills was still in Honolulu, although Bavasi, who was also in Hawaii on a cruise, said he thought the shortstop was in California. Wills was reported at a Democratic fundraiser starring Sammy Davis Jr. but brushed aside any questions about the situation. Kerlan said he still had not heard from Wills. Bavasi said there would be no discipline until all the facts were known. He said a post-World Series examination had found there was no need for an operation, but that if something had happened subsequently, Wills should be seeing Kerlan. “If he’s off playing the banjo somewhere, he must think the banjo is more important than baseball,” Bavasi said.45

Game 12: November 8, Okayama

The combined Yomiuri-Nankai team returned as the Dodgers’ opponents and fell 10-2. Ron Fairly and Nate Oliver hit home runs, but the Dodgers’ biggest contributor was John Roseboro with a double, two singles, and four RBIs. The 20,000 fans in Okayama Stadium saw the Dodgers score six runs, including Oliver’s home run, in the ninth inning to blow the contest open.

Game 13: November 9, Hiroshima

The Japanese opposition was now a team combining the Giants and members of the hometown Hiroshima Carp. The teams played to a 10-inning 10-10 tie before 18,000 at Hiroshima Municipal Stadium. Earlier in the day, a 25-person Dodger delegation had placed a wreath on the site of the atomic bomb’s impact. The game was called because of the need to meet the travel schedule. The Dodgers built an early lead, 10-4 after seven innings, but the home team rallied with six runs in the eighth and ninth innings off Claude Osteen, Phil Regan, and Ron Perranoski. “Something is wrong with Osteen,” said Alston. “He just can’t seem to hit his stride on this tour. With 10 runs, we shouldn’t have had any trouble.”46 Dick Stuart, with two, John Kennedy, and Jim Lefebvre hit home runs to build the Dodgers’ early lead.

Game 14: November 11, Kumamoto

The series moved to the island of Kyushu, the Dodgers’ first move off the main island of Honshu. The opponent at Fujisaki Stadium was a team combined from the Giants and the Nishitetsu Lions, based in the nearby city of Fukuoka. Alan Foster and Ron Perranoski held down the locals while Jim Lefebvre produced two run-scoring doubles to propel the offense. Foster limited the Japanese to one hit until he tired in the eighth inning. With the 6-3 win, the Dodgers’ record stood at 9-4-1. They would not win another game.

Game 15: November 12, Fukuoka

The teams moved to Fukuoka’s Heiwadai Ball Park and the Japanese shut down the Dodgers, 4-0. Joe Moeller gave up all the runs in the first four innings. It was the National League champions’ fifth loss of the tour, the most by any visiting American professional club.

Game 16: November 14, Kokura

Moving to the northern tip of Kyushu, the Dodgers dropped a 3-1 game to the Yomiuri Giants, moving their record to 9-6-1. Eighteen-year-old Tsuneo Horiuchi of the Giants held the Dodgers to six hits before 20,000 at Kokura Stadium. In the third inning, Dodgers starter Nick Willhite walked two batters before Sadaharu Oh came to the plate. Oh blasted one over the fence, but then was called out for passing the runner who had started at first base, limiting the benefit to two runs. The Giants’ final run scored three innings later when Akira Kunimatsu doubled in Oh. The defeat left the Dodgers’ record against the Giants at 3-3.

Game 17: November 15, Nagoya

Now facing a combined team from the Giants and the Chunichi Dragons, the Dodgers dropped their third in a row before 28,000 at Chunichi Stadium. Home runs by Sadaharu Oh and Toshimitsu Suetsugu powered the Japanese team. The Dodgers’ third loss in a row marked the first time an American team had suffered such a streak.

Also that day, the Japanese government awarded O’Malley its highest honor for a non-Japanese – the Order of the Sacred Treasure, Gold Rays with Neck Ribbon, recognizing his efforts to foster Japan-United States friendship through professional baseball.

The Dodger wives felt rewarded as well. The spouses of Tommy Dean, Bob Miller, Ron Perranoski, John Roseboro, Dick Stuart, and Jeff Torborg had made the trip and seen the sights and the cultural performances. And done some shopping. “I must have visited and bought out every department store in Japan,” said Sue Ellen Perranoski. “I bought a pearl ring, Christmas cards, kimonos, toys and a truckload of other things.”47

Game 18: November 16, Shizuoka

The tour, the worst by an American club in the history of the exchange, wound up with a 7-3 loss to the Yomiuri Giants, a game mercifully ended after seven innings because of darkness at Kusanagi Ball Park. It was the Dodgers’ eighth loss (9-8-1 overall) and their fourth straight defeat. Both were records for futility by an American team. For those viewing the tour as an international World Series, it meant the Giants had prevailed 4-3. The Giants jumped on Joe Moeller for four runs in the first inning and never looked back. The 21,000 in attendance saw Sadaharu Oh hit a grand slam, which would have been his third game in a row with a homer (and sixth for the series) except for his baserunning blunder in the 16th game. Al Ferrara homered in the Dodgers’ three-run sixth. Akio Masuda started and closed out his work with 3⅔ shutout innings.

The post-mortems started immediately. Giants manager Tetsuharu Kawakami said the series clearly showed that the gap between Japanese and American professional baseball had narrowed.

Comparing the 1966 tour to the one a decade earlier, he said, “We have learned a lot since then. Our baseball is at least 50 percent improved. Our bunting is better, the base runners are smarter now, and we play more inside baseball like the Americans.”48 Others were not so encouraged. Tokumi Matsumoto, a columnist for the Mainichi Daily News, quoted a fellow Japanese baseball writer: “It is obviously dangerous for the Japanese to believe the 9 win-8 loss-1 tie result indicates the Japanese pro ball standard is almost equal with that of the major leagues.”49

Dodgers manager Walter Alston said he was sorry over his team’s performance and offered specific praise for Oh, Masuda, and Horiuchi. He said he felt Japanese hitters, especially for power, had improved more than their pitchers since the Dodgers’ 1956 trip. Both managers noted that the absence of Koufax and Drysdale had had a big impact on the tour.50

After a day of relaxation and shopping on the 19th, the Dodgers’ charter plane left for Los Angeles on the 20th.

For the Dodgers, the consequences were coming. Some came directly from the tour. Others had been pending over the season.

The Dodgers party was still in Tokyo when the biggest blow fell. On November 18, Sandy Koufax announced that he was retiring. He knew he could keep competing and winning, but he also knew he risked permanent damage from an excruciatingly painful elbow that required extensive treatment before and after each start. O’Malley, still in Tokyo, wished him well.

As baseball’s Winter Meeting started on November 28, Bavasi started other planned changes. Former batting champion Tommy Davis, who had been on the trip, was traded to the New York Mets for the second baseman the Dodgers thought they needed – Ron Hunt. Three days later, the inevitable consequence of the Japan trip fell into place. Wills was traded to the Pittsburgh Pirates for Bob Bailey and Gene Michael. Wills eventually had left Hawaii and visited Kerlan in Los Angeles. Kerlan said the knee was no worse than it had been at the end of the season. He prescribed extended rest, which had been the basis of Wills’s request to miss the Japan trip. Bavasi said this was the only time Walter O’Malley had forced his hand on a baseball decision.51 Wills, evidently forgiven, returned to the Dodgers in 1969.

The remake of the Dodgers’ roster would not work well. The team fell into the second division for two years and wouldn’t win another pennant for eight years, or another World Series until 1981.

Walter, and later Peter, O’Malley worked hard to improve and deepen relations with Japanese baseball. Yomiuri sent the Giants (and 21 Japanese reporters) to Vero Beach for joint spring training with the Dodgers in 1967. The Giants, or individual players, returned many times in the future and other Japanese professional and college teams would come for spring training. The Dodgers did not return to Japan until 1993, but these decades-long contacts were instrumental in the Dodgers’ ability to sign Hideo Nomo when he became the first major Japanese star to join an American major-league team in 1995.

The agreement between the two commissioners had sparked Japanese dreams that they were evolving toward parity with the US major leagues. The relationships the O’Malleys and the Dodgers forged with Japanese baseball were instrumental in giving them the opportunity to sign Nomo, and effectively confirm Japanese baseball as a second-tier operation as its major stars could dream of better salaries and the satisfaction of competing successfully at the highest levels of professional baseball.

ANDY McCUE, a former Board President of SABR, won the Seymour Medal for Mover and Shaker: Walter O’Malley, the Dodgers, and Baseball’s Westward Expansion. He is also the author of Baseball by the Books: A History and Complete Bibliography of Baseball Fiction and Stumbling Around the Bases: The American League’s Mismanagement in the Expansion Eras (University of Nebraska Press, 2022). He holds a master’s degree in Chinese history.

Sources

In addition to the specific books and articles cited below, this essay drew on the Japan Times, Pacific Stars and Stripes, Honolulu Star-Bulletin, Honolulu Advertiser, Los Angeles Times, The Sporting News, baseball-reference.com, retrosheet.org, and walteromalley.com.

(Click images to enlarge)

Notes

1 Robert K. Fitts, Mashi: The Unfulfilled Baseball Dreams of Masanori Murakami, the First Japanese Major Leaguer (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2015).

2 “Japanese Ignore Terms of Agreement,” The Sporting News, June 26, 1965: 14.

3 https://www.walteromalley.com/en/dodger-history/international-relations/Overview_Page-1 retrieved September 15, 2021.

4 “Japanese Ignore Terms of Agreement.”

5 “Dodgers Fall Easily to Met Unknowns, 4-1,” Los Angeles Times, March 16, 1966: III, 3.

6 United Press International (UPI), “Dodgers Invited for Japan Tour,” Honolulu Advertiser, April 19, 1966: C-4.

7 UPI, “Dodgers Get Japan Trip OK,” Honolulu Advertiser, May 4, 1966: B-6.

8 Frank Finch, “Wills Plays as Bavasi Burns,” Los Angeles Times, February 18, 1966: III, 1.

9 UPI, “Wills to Sign for $80,000,” Honolulu Advertiser, March 10, 1966: B-4. Salaries are from Baseball-reference.com.

10 Bob Hunter, “Drysdale Weighs Japan Offer: Dodger Star Can Have $500,000,” Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, September 9, 1965: F1.

11 Bob Hunter, “Drysdale Faces Ban if He Plays Baseball in Japan,” The Sporting News, September 25, 1965: 4.

12 Bob Hunter, “Koufax, Drysdale Ask Dodgers for Million$,” Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, February 22, 1966: A1.

13 Frank Finch, “Koufax, Drysdale Spurn Record Offer by Dodgers,” Los Angeles Times, February 25, 1966: III, 1.

14 Paul Zimmerman, “… K&D Are Making Other Plans,” Los Angeles Times, March 17, 1966: III, 1.

15 Charles Maher, “Peace at Last! K&D Return to Fold,” Los Angeles Times, March 31, 1966: III, 1. The amounts reported at the time varied somewhat, but the $125,000 and $110,000 figures emerged later.

16 Marvin Miller, interview, April 18, 2001.

17 Associated Press, “Victory Bath: Champagne and Shaving Cream,” Los Angeles Times, October 3, 1966: III, 1.

18 Red McQueen, “Dodgers Balk at Japan Trip,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, June 12, 1966: 65.

19 Jim Hackleman, “The Hack Stand,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, August 17, 1966: C-9.

20 UPI, “Sutton Unable to Make Trip,” Honolulu Advertiser, October 12, 1966: 22.

21 Bob Hunter, “Big D Could Furnish Answer to ‘X’ on Dodgers’ Hill Staff,” The Sporting News, January 28, 1967: 26.

22 Frank Finch, “Dodgers Follow Goodwill Tour of Maryland with One to Japan,” Los Angeles Times, October 14, 1966: III, 1.

23 Jim Hackleman, “Dodgers Kick Runless Habit,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, October 17, 1966: B1; Jim Hackleman, “Dodgers Rout Old Enemy,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, October 18, 1966: C2.

24 Frank Finch, “International World Series with Japan Moving Nearer to Reality,” Los Angeles Times, October 19, 1966: III, 7.

25 Robert Trumbull, “Dodgers (U.S.) to Play Giants (Japan),” New York Times, October 5, 1966: 51.

26 Far East Network, “Dodger Tour Set on FEN,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 20, 1966: 20.

27 Lee Kavetski, “L.A. Arrives: ‘WOW!’, Thundering Japan Welcome,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 22, 1966: 18.

28 UPI, “Dodgers Here to Play 18 Exhibition Games,” Japan Times, October 21, 1966: 6.

29 Kavetski, “L.A. Arrives.”

30 https://www.walteromalley.com/en/dodger-history/international-relations/1966-Japan-Tour_Page-1, Retrieved January 4, 2022.

31 Lee Kavetski, “L.A. Bombards Yomiuri 16-5,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, October 24, 1966: 19.

32 UPI, “Dodgers Get 21 Hits – in One Game,” New York Times, October 23, 1966: S2.

33 Associated Press, “Dodgers Back on Beam, Lose 5-0 on 3-Hitter,” Los Angeles Times, October 24, 1966: III, 8.

34 Arthur Daley, “Sports of the Times: Like an Echo,” New York Times, November 2, 1966: 50.

35 “Dodgers Trim Giants 3-1 for Second Win of Series,” Japan Times, October 24, 1966: 6.

36 Frank Finch, “Wills ‘Jumps’ Tour to Get Knee Treated,” Los Angeles Times, October 28, 1966: III, 5.

37 In three appearances against the Dodgers on this tour, Murakami surrendered three earned runs in six innings.

38 Charles Maher, “O’Malley Charges Wills ‘Embarrassed’ U.S., Plans Personal Apology to Japanese Premier,” Los Angeles Times, November 3, 1966: III, 1.

39 Charles Maher, “Sportscaster ‘Finds’ Wills in Hawaii,” Los Angeles Times, November 6, 1966: D3.

40 Lee Kavetski, “L.A. Adjusts Winningly,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 4, 1966: 18.

41 Lee Kavetski, “Dodgers Learn Oh Plus Eto equals ‘Ouch,’” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 7, 1966: 20.

42 Lee Kavetski, “Dodgers Can’t Shed the Monkey, Lose Again,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 8, 1966: 20.

43 “Eckert, O’Malley Give Gifts to Sato,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 6, 1966: 17.

44 Frank Finch, “As Diplomats, Dodgers Succeed in Japan,” Los Angeles Times, November 8, 1966: III, 3.

45 Maher, “Sportscaster ‘Finds’ Wills.”

46 Associated Press, “Dodgers Blow Lead; Game Ends in Tie,” Los Angeles Times, November 10, 1066: III, 7.

47 Associated Press, “Shopping Spree,” Japan Times, November 16, 1966: 6.

48 Frank Finch, “Japanese Make 50% Gain in Baseball, Says Manager,” Los Angeles Times, March 2, 1967: Part III, 3.

49 Tokumi Matsumoto, “Have Japanese Reached Big League Level?” The Sporting News, December 10, 1966: 14.

50 “Oh Belts Grandslammer in Giants’ 7-3 Win Over L.A.,” Japan Times, November 17, 1966: 6.

51 Author interview with Buzzie Bavasi, November 30, 1994.

52 Listed Japanese players have a minimum of 5 at-bats, 3 innings pitched, or a decision. Yoshikazu Matsubayashi, Baseball Game History: Japan vs, U.S.A. (Tokyo: Baseball Magazine, 2004), 96; Nippon Professional Baseball Records, https://www.2689web.com/nb.html.