1977: When Earl Weaver Became Earl Weaver

This article was written by Bryan Soderholm-Difatte

This article was published in Fall 2011 Baseball Research Journal

All managers think about strategy, but one can argue that no manager this side of John McGraw changed our prevailing understanding of baseball strategy as much as Earl Weaver. In his seminal work, Weaver on Strategy, and in various quotations uttered while holding court, Weaver presented insights that may have long been implicitly understood by the best thinkers on the game—whether managers, players, or sportswriters—but which did not articulate basic principles as universal truths the way he did. Most notably, Weaver stressed, “Your most precious possessions on offense are your twenty-seven outs.”[fn]Earl Weaver with Terry Pluto, Weaver on Strategy (Potomac Books, 1984), 39.[/fn]

Until Weaver called attention to it, the concept of only twenty-seven outs was—and perhaps still too often is—lost in the actual playing of the games. Managers may resort to various stratagems to try to seize an advantage, particularly in the early and middle innings, at the expense of thinking about the long arc of a game. Weaver’s constant awareness of the potential importance of each out was at the very core of the offensive strategies that characterize his legacy.

WEAVER’S GRAND STRATEGY

Earl Weaver as a grand strategist is remembered today for his philosophy on the merits of the three-run home run (he subtitled the chapter on offense in Weaver on Strategy “Praised Be the Three-Run Homer”), disdain for run-creation strategies (they cost outs and are inefficient), and deliberately building his bench with pinch hitting and substitution options for position players in anticipation of batter-pitcher matchups. This also allowed him to platoon in his daily starting line-up with nearly wild abandon. “You need someone for each job that needs to be done when the time arises,” he wrote.[fn]Weaver on Strategy, 25.[/fn] Weaver was a manager with a plan for every individual player on his team. The Earl of Baltimore did not want mere emergency back-up players on the bench, who rarely played but were there when needed. He didn’t just want “utility” players who could play a variety of positions, or a power bat from each side of the plate. He had in mind a specific set of roles—that’s plural—for each player sitting on the Baltimore Orioles’ bench. He knew what each could do in particular situations against particular pitchers, and used them often and accordingly. Everybody played, and he expected them all to contribute.[fn]The Bill James Guide to Baseball Managers From 1870 to Today (Scribner, 1997), 243–245.[/fn]

Earl Weaver as a grand strategist is remembered today for his philosophy on the merits of the three-run home run (he subtitled the chapter on offense in Weaver on Strategy “Praised Be the Three-Run Homer”), disdain for run-creation strategies (they cost outs and are inefficient), and deliberately building his bench with pinch hitting and substitution options for position players in anticipation of batter-pitcher matchups. This also allowed him to platoon in his daily starting line-up with nearly wild abandon. “You need someone for each job that needs to be done when the time arises,” he wrote.[fn]Weaver on Strategy, 25.[/fn] Weaver was a manager with a plan for every individual player on his team. The Earl of Baltimore did not want mere emergency back-up players on the bench, who rarely played but were there when needed. He didn’t just want “utility” players who could play a variety of positions, or a power bat from each side of the plate. He had in mind a specific set of roles—that’s plural—for each player sitting on the Baltimore Orioles’ bench. He knew what each could do in particular situations against particular pitchers, and used them often and accordingly. Everybody played, and he expected them all to contribute.[fn]The Bill James Guide to Baseball Managers From 1870 to Today (Scribner, 1997), 243–245.[/fn]

The philosophy now identified with Weaver reflects where he was at the end of his brilliant career, but the core elements were in place at least a half-decade before he retired following the 1982 season. His philosophy began to evolve the day he took over the Orioles in mid-season 1968. While the basic principles of Weaver’s grand strategy were perhaps always there for him, they developed into a coherent narrative through his experiences in the first half-dozen years or so that he managed the Orioles. At least, that’s what the data indicate from the games Earl Weaver managed.

Nineteen seventy-seven appears to have been the year where Weaver’s application of his strategic principles first became consistently discernible. The following analysis is based on data compiled through the extraordinary efforts of Retrosheet and available on the website Baseball-Reference.com for Earl Weaver’s 14 full seasons as Baltimore Orioles manager from 1969 to 1982.[fn]Weaver returned for an encore at the request of Baltimore’s owners in mid-season 1985 and managed the Orioles for all of 1986, but this was an interruption in his retirement to try to right a suddenly-failing franchise. (Weaver on Strategy, 189.)[/fn]

THE HOME RUN IS ABOUT SCORING BIG

The fundamental premise of Weaver’s offensive strategy was: “In my mind, the home run is paramount, because it means instant runs.”[fn]Weaver on Strategy, 34.[/fn] Since the end of the Deadball Era, any manager who had sluggers on his team loved the three-run home run. Miller Huggins certainly did with Ruth and Gehrig, Joe McCarthy with Gehrig and DiMaggio, Casey Stengel with Mantle and Berra. Even McGraw—who was a loud-mouthed evangelist for “scientific” small ball as the best way to score runs[fn]Lyle Spatz and Steve Steinberg, “1921: The Yankees, the Giants, and the Battle for Baseball Supremacy in New York,” The Baseball Research Journal, Fall 2009 (Volume 38, number 2), 12–13.[/fn]—surely appreciated first baseman George Kelly as one of the National League’s premier home run hitters when the Giants won four straight pennants from 1921 to 1924, not to mention young slugger Mel Ott who hit 42 home runs for him in 1929. Small ball has its place, but as Weaver said, there is no more sure or faster way to score runs than with a home run, especially with runners already on base.

None of Earl Weaver’s teams, however, ever led the American League in homers, which of course belies his faith and commitment to the home run. In his 14 full seasons as manager, Weaver had only two of his players finish in the top three in home runs—Eddie Murray, who tied with three others for the league lead in the strike-disrupted 1981 season, and Reggie Jackson who finished second in 1976 (his only year in Baltimore). But though the Orioles under Weaver never had more than the third-highest home run total in the league, when they did peak at third, it coincided with their pennant-winning years of 1969, 1970, and 1979, then again in 1976, 1978, and 1982. Weaver nonetheless usually did have a pair of dangerous power hitters who delivered in the middle of his line-up—Frank Robinson and Boog Powell when he won three straight pennants from 1969 to 1971; Lee May and Don Baylor in 1975; May and Reggie Jackson in 1976; May and Eddie Murray in 1977 and 1978; Murray, Ken Singleton, and his left field platoon of Gary Roenicke and John Lowenstein from 1979 to 1982. These guys could make the three-run home run happen with some measure of frequency. The only years Weaver’s Orioles lacked consistent power were 1972 to 1974, after Frank Robinson had been traded away and as Powell got older, and before the arrivals of May, Singleton, and Murray.

THE ORIOLES’ SACRIFICES

It is well known that Earl Weaver hated the sacrifice bunt as wasting a precious out: “There are only three outs an inning, and they should be treasured. Give one away and you’re making everything harder for yourself.”[fn]Weaver on Strategy, 38.[/fn] It is not that Weaver thought that bunting was never appropriate—“I’ve got nothing against the bunt—in its place”[fn]Ibid., 33.[/fn]—but that its place was limited to where it gave his team a chance to win a game in the late innings.

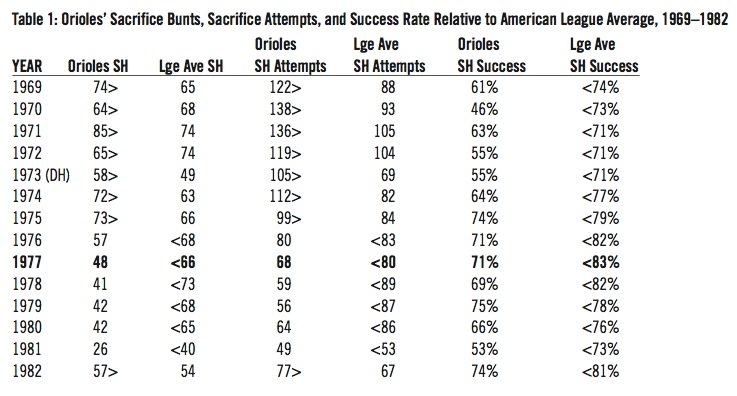

None of his teams ever led the league in sacrifices, but in Weaver’s first seven full seasons as manager, the Orioles were in the top three of the 12 American League teams in sacrifice bunt attempts every year. In four of those years, Baltimore had more sacrifice attempts than any other team in the league, and twice the second most. We must allow, however, for the fact that until 1973, when the designated hitter rule went into effect, American League pitchers were still required to hit for themselves. Exactly half of the 288 sacrifice bunts laid down by the Orioles from 1969 to 1972 were by the pitcher, according to the data, and Weaver’s pitchers had more opportunities to attempt a sacrifice both because the on-base-percentage (OBP) of Baltimore batters (not including pitchers) in the bottom third of the order was generally comparable to the team’s OBP as a whole, and because Baltimore’s superior starting rotation often pitched late into games allowing them more plate appearances.

Even after the DH came into being, however, the Orioles still led the league in sacrifice attempts the first two years, and were third the year after that (1975). But these years coincided with Baltimore’s (temporary) drop in home run power, previously mentioned. It wasn’t until 1977 that the number of sacrifice attempts ordered by Weaver dropped dramatically. In 1978 and 1979, the Orioles were last and next to last in the league in attempted sacrifices, in 1980 they attempted the third fewest, and in 1981 the fifth fewest. After averaging 99 sacrifice attempts per year from 1973 (the first year of the DH, so no pitchers batting) to 1976, Weaver’s Orioles averaged 65 per year from 1977 to 1982, not including the 1981 strike-shortened season, a 34-percent drop.

There are two other indicators of Weaver disdaining the sacrifice even more after 1977 than before. From 1969 to 1976, according to the data, 64 percent of Baltimore’s sacrifice bunts came in victories and 22 percent in the seventh inning or later with the score tied, the Orioles ahead by one, or behind but with the potential tying run on base, at the plate, or on deck. From 1977 to 1982, by contrast, 75 percent of the Orioles’ sacrifices came in victories, and only 15 percent in the seventh inning or later in close games. This means that Weaver became more reluctant to bunt both when his team was losing and when his team needed a run in a close game in the late innings. In either situation, it is apparent Weaver was more inclined after 1977 to let his hitters hit—looking for that home run to instantly make up ground, or for hits to get more runners on base and drive in runs.

Weaver was consistent throughout his managerial career in rarely bunting a runner over when there was already one out in the inning, except when American League pitchers had to bat. It is worth noting, however, that with a runner on second base and first base open, including with nobody out, Weaver’s Orioles laid down a total of only 11 sacrifice bunts in the six years from 1977 to 1982, compared to 32 in the four years from 1973 (the beginning of the DH) to 1976. In this circumstance, after 1977, Weaver was most clearly not of a mind to sacrifice an out to get a runner already on second over to third; better to try to drive him home with a hit.

Weaver’s disdain of the sacrifice bunt was further validated by the Orioles’ routinely poor percentage in successfully laying them down. The Orioles had a worse success rate in sacrifice attempts than the league average every one of Weaver’s 14 full seasons at the helm, generally far below average. Weaver’s Orioles actually attempted 112 more sacrifice bunts than the average American League team, but were successful only 63 percent of the time, while the AL average was 76 percent. Weaver himself wrote: “Since a manager should only have those hitters bunt who have the skill, about 80 percent of your sacrifices should be successful.”[fn]Ibid., 41.[/fn] Mastering the bunt may not have been part of the famed “Orioles Way,” but the Orioles’ frequent inability to bunt successfully certainly made going for the base hit—or better yet, the home run—a more compelling option.

ORIOLES NOT SO PRODUCTIVE IN MAKING PRODUCTIVE OUTS

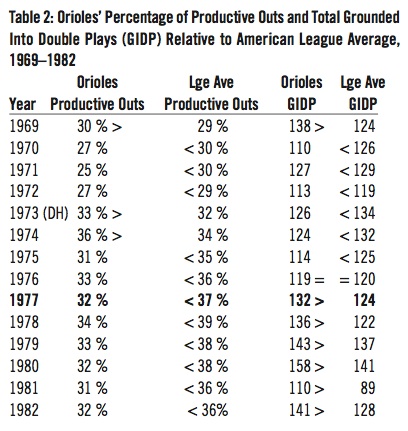

The 1970s and early-1980s Orioles generally were not very good in advancing base runners, perhaps because this was not important to Weaver even at the beginning of his managerial tenure. Besides disdaining the bunt, Weaver did not want to sacrifice outs just to move a runner over, whether by hitting behind the runner or even the more dynamic hit-and-run. He considered the hit-and-run “the worst play in baseball”[fn]Ibid., 47.[/fn] In the statistical category of making productive outs—defined by Baseball-Reference.com as a batter advancing any runner with nobody out or driving home a runner with the second out of an inning—the Orioles were below the league average every year Weaver was manager except for 1969, 1973, and 1974.

While Weaver’s Orioles remained relatively consistent in percentage of productive outs, 1977 represents a break point. From 1969 to 1971, while winning three straight pennants, Baltimore batters made productive outs in 27 percent of their opportunities with runners on base, compared to the American League average of 30 percent. And from 1972 to 1976, most years in which Weaver did not have an imposing pair of power hitters in the heart of his batting order, Orioles’ hitters made productive outs in 32 percent of their chances to move up or score a runner, when the league average was only slightly higher at 33 percent. But from 1977 to 1982, Baltimore’s 32 percent success rate in productive outs was substantially below the league average of 37 percent.

The frequency of Baltimore batters grounding into double plays relative to the rest of the league is yet another metric that suggests Weaver’s disdain for small ball and his desire for his batters to hit with runners on base really took off in 1977. Since Weaver did not put on plays to advance his base runners, the potential for double plays increased. Indeed, wrote Weaver, “About the only thing you can say for the hit-and-run is that it prevents the double play grounder.”[fn]Ibid., 47.[/fn] In Weaver’s first eight full seasons as manager—1969 to 1976—his Orioles hit into fewer double plays than the league average every year except for 1969. But from 1977 till Weaver retired in 1982, Baltimore not only hit into more double plays than the league average, but substantially more; the 820 double plays Weaver had to watch his team hit into from the dugout those six years was 11 percent more than the league average of 741 per team.

STOLEN BASES OK

While the stolen base was one small ball strategy that Weaver did have use for, he also warned that “the failed stolen base attempt can be destructive, particularly at the top of the order, because it takes the runner off the base paths ahead of your home run hitters.”[fn]Ibid., 44.[/fn] Unlike sacrifice bunts and hitting behind the runner, at least a caught-stealing did not give up the batter as an out. With talented base stealers like Don Baylor in the mid-1970s and Al Bumbry after that, Weaver was willing to regard the stolen base attempt as an acceptable risk. In his 14 years as Baltimore manager from 1969 to 1982, Weaver had at least one player steal 20 or more bases sixteen times, including three players in 1974 and 1976.

Until his last two years as manager, when Baltimore was fourth and third in the league in fewest steals, Weaver appears to have been comfortable with the stolen base as a tactic. The Orioles led the league in steals in 1973, were third in 1974, and were typically well above the league average in successful stolen base attempts. There were only three years—including the last two before he retired (the first time)—that Weaver’s Orioles were below the league average in stolen base percentage. Nonetheless, his Orioles were successful 66 percent of the time during his tenure, substantially below the 75 percent Weaver believed was necessary for the steal “to be worthwhile.”[fn]Ibid., 44.[/fn]

WEAVER AND THE PLATOON ADVANTAGE AT BAT

Earl Weaver was also acclaimed for seeking to gain the advantage in batter-pitcher match-ups during games when it mattered most. Although other managers long before him were aware of how their batters matched up against certain pitchers, Weaver was probably the first to be so systematic about it. In the late 1940s, the Brooklyn Dodgers’ statistician, Allan Roth, pioneered the keeping of these kinds of statistics, but outside of Burt Shotton, Dodgers managers chose not to rely on them.[fn]Joshua Prager, The Echoing Green: The Untold Story of Bobby Thomson, Ralph Branca and the Shot Heard Round the World (Vintage Books, 2008), 183[/fn] For the most part, when managers went to their bench to play the percentages with a pinch hitter, all that basically mattered was who was available who batted from the opposite side the pitcher threw. There was, of course, strategizing as to who to use when—managers would choose when to pinch hit a slap-hitting speed guy to get a rally started and when to send in a big bopper to drive in runners or to make it a game again with one mighty blow. But it was Weaver who was ahead of his time in using statistical-based analysis to determine the make-up of his bench and decide at potential turning points in the game which of his hitters had the best chance of coming through in the clutch.[fn]Weaver on Strategy, 25–26, 52–53[/fn] These were informed decisions by Weaver, based on players’ past performance.

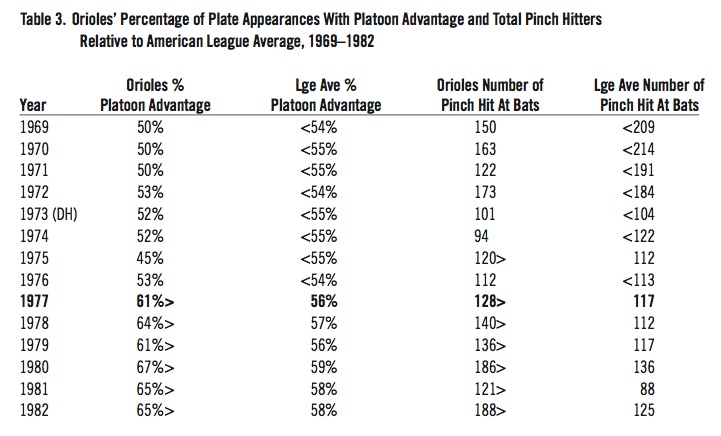

Earl Weaver almost always had a regular platoon at one position or another—most famously the left-handed batting John Lowenstein with the right-handed batting Gary Roenicke in left field from 1979 to 1982—and sometimes he platooned players at two or three positions at any one time. But for most of the first half of his career as Baltimore manager, Weaver’s seeking the platoon advantage in any given at bat was not out of the ordinary compared to other managers. From 1969 to 1976, there was not one single year in which the Orioles exceeded the league average in percentage of plate appearances where they had the platoon advantage—defined as a batter facing a pitcher throwing from the opposite side. Not one. American League teams on average during those eight years had a platoon advantage against the pitcher in 54 percent of their plate appearances; for Weaver’s Orioles, the annual average was 51 percent.

Aside from 1975, when the Orioles had the platoon advantage in 45 percent of their plate appearances, compared to 55 percent for the league as a whole, it is not surprising that the biggest gap between the Orioles and the rest of the league—9 percent fewer plate appearances with the platoon advantage—was when Baltimore dominated the American League by winning three consecutive blowout division titles and pennants from 1969 to 1971, during which they also led the league in scoring twice and were second in 1969. These were the years when Weaver had his most stable daily line-up, with Boog Powell at first, Davey Johnson at second, Mark Belanger at short, Brooks Robinson at third, and Don Buford, Paul Blair, and Frank Robinson in the outfield. Powell and Buford (who was a switch hitter) were the only left-handed bats among his core regulars. That’s every regular position on the field except catcher, where Weaver platooned the left-handed Elrod Hendricks with the right-handed Andy Etchebarren.

Although Weaver gave Frank Robinson and Buford more days of rest in 1970 and 1971, his seven core players at the seven positions behind the pitcher each met the major league minimum of 502 plate appearances to qualify for the batting title in every one of those three years. After 1971, Weaver’s teams never had more than five players in any given year play 130 or more games in the field and have enough plate appearances to qualify for the batting title, except in 1975 (he had six), when the Orioles had their biggest deficit in the platoon advantage relative to the rest of the league. In five of Weaver’s ten seasons as manager after the DH came into effect, the Orioles’ designated hitter also had enough plate appearances to meet the major league minimum.

Once again, 1977 was the year Weaver changed his dynamic. From 1977 through 1982, Weaver managed his offense to ensure that the Orioles had the platoon advantage in any given plate appearance 64 percentage of the time—substantially higher than the 57 percent averaged by the now-fourteen teams in the American League. In Weaver’s last three years as manager before he decided to retire, the Orioles were second in 1980 and first in the league in 1981 and third in 1982 in platoon advantage at the plate. Having a pair of dangerous switch hitters from either side of the plate all six of those years in Eddie Murray and Ken Singleton, who could always bat from the opposite hand of the pitcher, certainly helped Weaver attain such a high platoon advantage.

In the DH era, AL managers wanting a platoon advantage at the plate had to pinch hit for position players. With his carefully constructed bench, and his copious notes on Orioles batters versus particular pitchers, Weaver gained a deserved reputation as the mastermind of pinch hitting. In 1977 this Earl Weaver trait became clearly apparent. In his first three full seasons as manager, Weaver sent the fewest pinch hitters to the plate of any AL manager twice—in 1969 and 1971—and only Boston’s manager Eddie Kasko made fewer in 1970. This statistic is misleading, however, because pitchers still had to bat in the American League and Weaver had the best starting rotation on the most dominant team in the league. His staff had the lowest starters’ ERA in the league all three years, had the highest percentage of quality starts, and averaged the most innings pitched per start in the last two years, and were second the first year.

With pitchers the caliber of Jim Palmer, Mike Cuellar, and Dave McNally anchoring his rotation all three years—joined by Pat Dobson in 1971 to become only the second major league team in history (after the 1920 Chicago White Sox) to have four 20-game winners—and the Orioles also prolific in scoring runs, Weaver had little occasion to pinch hit for his pitchers. Moreover, Weaver was willing let his starters go the distance if they had the lead and were pitching well. Sparky Anderson, Weaver was not.

Once the DH came along, Weaver was generally in the mainstream when it came to pinch hitting for position players through 1976. In the first four years of the DH, the Oriels averaged 107 pinch-hit at bats per year, five percent fewer than the league average per team. Then from 1977 to 1982, Weaver sent a pinch hitter to the plate an average of 150 times per season, 29 percent more often than the league average of 137.

WEAVER’S POSITION PLAYER SUBSTITUTIONS

All of this is consistent with the total number of in-game position substitutions Earl Weaver made as manager of the Baltimore Orioles, with 1977 once again a clear delineation. In his first four full seasons as manager, Weaver was not at the high end of managers substituting for position players. But of course, the quality of Baltimore’s core regulars those years—at least from 1969 to 1971—was such that there was likely little to be gained for Weaver to replace players during games beyond resting his starting position players every now and again. Weaver made an average of 159 position player substitutions per year while winning three straight pennants, allowing his position players to complete 88 percent of the games they started, according to data in Retrosheet.[fn]Position player substitutions are the difference between the total number of player games at each position (other than pitcher) and the total number of position games, which is calculated as eight positions (not including pitcher) times the number of games played by the team that year.[/fn] In 1972, the last year American League pitchers had to hit for themselves, Weaver made 198 position player substitutions, allowing his starters to stay in the game 84 percent of the time.

In the first four years of the DH, Weaver began rising to the top tier of American League managers making position player substitutions, averaging 215 per season. The percentage of games completed by the Orioles’ starting position players dropped from 87 percent in 1974, to 83 percent in 1975, and 81 percent in 1976. The major reason for this was that power-hitting first baseman Lee May, who was not especially gifted defensively, completed only 66 percent of the 142 games he started at first in 1975 and 52 percent of the 93 games he started there in 1976. Weaver also started May at DH in 51 games in 1976.

Beginning in 1977 until he retired after the 1982 season, and not counting the strike-shortened year of 1981, Weaver never again made fewer than 300 in-game position substitutions, usually precipitated by pinch hitting for an advantage. And in 1981, the 239 substitutions he made projected to equal 369. Weaver made 387 position player substitutions in 1977—52 percent more than in 1976—and the percentage of position players who completed the games they started was down to 71 percent. May and rookie Eddie Murray—both of whom also started in the DH role— completed only 55 percent of their starts at first base. Over the next five years, Weaver’s starting line-up of position players (not including the DH) completed only 76 percent of their games, meaning that on average in any given game, two of his eight starters who took the field in the first inning were out of the game before it ended.

The jump from the annual average of 192 position substitutions in Weaver’s first eight seasons to 312 in his last six years beginning in 1977 was dramatic and indicative of Earl Weaver consolidating into enduring practice two of his most fundamental tenets. One, he prized fielding to back up his pitching staff. Two, he prioritized batter match-ups at key moments of the game. Particularly in the last half of his tenure as Baltimore manager—when he no longer had seven position players who should indisputably take the field every day—Weaver put together teams that had redundancy at virtually every position, giving him options for both pinch hitting and defensive replacements.

The only position players who were assured the likelihood of finishing the games they started in Weaver’s final six years as Baltimore manager were first baseman Eddie Murray, third baseman Doug DeCinces (until he was traded to the Angels before the 1982 season), center fielder Al Bumbry (most years), and shortstop Cal Ripken in 1982. Even Ken Singleton, one of the best outfielders in the American League, was in the game at the end of only 52 percent of the 643 games he started in right field from 1977 to 1981. Despite Singleton’s prodigious offensive production—averaging 23 home runs, 89 RBIs, and .301 at the plate—Weaver felt his defense left much to be desired. By 1982, Singleton was the Orioles’ DH. When he had his two best years in 1977 (24 home runs, 99 RBI, a .328 batting average, and a .438 on-base percentage) and 1979 (35 home runs, 111 RBI, a .295 batting average, and a .405 on-base percentage), Singleton still completed only 61 percent of the games he started in right field both seasons.

The outfield was where Earl Weaver made the preponderance of his in-game substitutions from 1977 to 1982. For those six years, outfielders in his starting line-up were still in the game when the final out was made only 65 percent of the time. In some respects, Weaver’s frequent in-game substitutions of outfielders harkened back to George Stallings’ model with the 1914 “miracle” Boston Braves, the year Stallings made platooning famous. Weaver had Singleton and Bumbry starting most often in right and center and used Roenicke and Lowenstein as a platoon in left (whereas Stallings had, maybe, only Joe Connolly of that caliber among his outfielders). But Weaver also always had some combination of the left-handed Pat Kelly, Tom Shopay, Larry Harlow, and Jim Dwyer and the right-handed Andres Mora, Carlos Lopez, and Benny Ayala on his bench to pinch hit and play the outfield as needed, which was often.

The Orioles’ infield was also not immune to Weaver’s substitutions. From 1978 to 1980, Weaver started Kiko Garcia at shortstop in 237 games—almost exactly half of the total games Baltimore played, with Mark Belanger starting most of the rest—but kept him in the game in only 130 of them. Belanger, one of the best defensive shortstops ever, usually finished up for Garcia. Meanwhile, Lenn Sakata was a versatile infielder who often took over second base for Rich Dauer.

MORE WINS THAN EXPECTED AFTER 1977

Whatever one thinks of the merits of Weaver’s grand strategy, it is likely not a coincidence that his Baltimore Orioles exceeded their “Pythagorean” wins expectancy every season beginning in 1977. From 1977 to 1982, the Orioles won 35 games more than projected based on their runs scored versus runs allowed, an average of 5.8 extra wins per year. The only manager in history besides Weaver to exceed his team’s Pythagorean expectancy to such an extent for as many consecutive seasons was Joe Torre with the 2001–06 Yankees.[fn]Pete Palmer and Gary Gillette, ESPN?Baseball Encyclopedia (Sterling Publishers, 2008).[/fn] That the Orioles won only one division title (and one pennant) in that time and still won nearly six games a year more than they should have suggests Weaver’s philosophy was responsible for the Baltimore Orioles being as good and competitive as they were. Weaver’s approach to building his teams so that he had maximum flexibility for making moves during games, of seeking the platoon advantage at bat in key situations, of not sacrificing outs just to move base runners along, and of trying to score runs by batting them in—preferably in bunches with three-run home runs—made his Baltimore Orioles one of the toughest teams to beat.

BRYAN SODERHOLM-DIFATTE lives and works in the Washington, D.C., area and is devoted to the study of baseball history. His website, www.thebestbaseballteams.com, identifies the best teams of the twentieth century in each league using a structured methodological approach for analysis.