20-Game Loser: Profiles of the 20-Loss Seasons

This article was written by David E. Skelton

This article was published in Spring 2013 Baseball Research Journal

It has become almost as rare as the major-league Triple Crown, and even more so than its statistical opposite of a pitcher winning 20 games in a single season. Since 1980, there has been only one pitcher who lost 20 games in a single season—21 to be exact—and there is no reason to think baseball will see another such season in the foreseeable future. It has become baseball’s equivalent of Bigfoot: seemingly rumored to exist, but impossible to see.

Historically, it didn’t used to be this way. Prior to 1980, baseball saw a fairly regular sprinkling of pitchers with at least 20 losses per season. The roster of said pitchers was remarkably diverse: from the pitcher who approached the mound with the expectation of sinister, scary music, to the later Hall-of-Fame inductee.

Historically, it didn’t used to be this way. Prior to 1980, baseball saw a fairly regular sprinkling of pitchers with at least 20 losses per season. The roster of said pitchers was remarkably diverse: from the pitcher who approached the mound with the expectation of sinister, scary music, to the later Hall-of-Fame inductee.

As opposed to delving into the reasons for this paucity (of which there are many), the research herein has instead focused on the unique circumstances surrounding many of these past 20-game losers. This research has been limited to the period from 1920 to the present—a time when the 20-loss season was not rare, but not as pervasive as the preceding period when, for example, from 1900-20, there was an average of five or more pitchers logging 20 losses per season (with a high of 14 such pitchers in 1905). Therefore, unless otherwise cited, the statistical “leaders” noted in the 20-loss/season category are limited to the last 92 years Barring an unlikely rash of any future 20-loss seasons, these statistics will likely stand for many years to come.

For purposes of capturing the 20-loss “achievement”, the following categories have been established: The Deserved, The Repeat Offenders, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, The Unjustified, Miscellaneous, and The Teammates.

As described below, these categories are not intended as “hard” boundaries. A pitcher slotted in “The Repeat Offenders” column could easily slide two categories later (Phil Niekro, for instance), or justifiably be listed under two separate columns (Dick Ellsworth: The Deserved and The Repeat Offenders). The intention herein is not to pursue a thorough analysis of the 20-loss season as much as establish a sorting for purposes of relating the rather interesting events, statistical anomalies and, in some instances, ironies that helped lead these pitchers into such an exclusive club.

Furthermore, at no point in these brief statistical summaries should the reader perceive intent to belittle or denigrate the pitchers cited. In fact, it is often to the contrary, as any hurler who accumulated as many as 20 losses had to have had a certain level of confidence from his manager to have taken the mound so regularly. As will be seen, these same 20-loss “victims” were often the staff aces hurling for some rather pathetic teams.

Staff ace or not, the pitchers and their stories tell an interesting tale.

THE DESERVED

In deference to the above-referenced “cue the sinister scary music” there are certainly some pitchers whose particular season appears to beg 20 losses. Notwithstanding the success achieved in other years, they include (in no particular order):

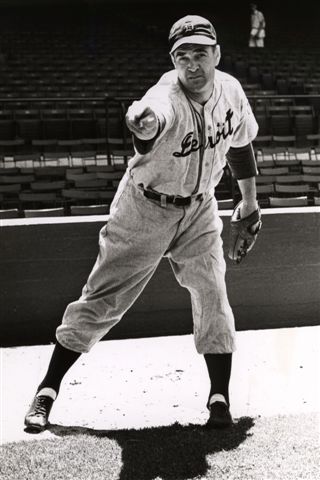

Mike Maroth, Detroit Tigers (2003)

Mike drew the Opening Day assignment for the Tigers to start the 2003 season, and the 3–1 loss to the visiting Minnesota Twins would seemingly portend the ominous season ahead for both Maroth and the Tigers. The team went on to establish an American League record for losses in a season—one shy of the post-1900 low mark set by the expansion New York Mets in 1962—while Maroth would go on to etch his name in the long list of pitchers with 20 losses.

The Tigers were in the midst of a 12-year drought of consecutive losing seasons, and in 2003 management moved to reverse this trend with a full scale youth movement (every starting pitcher was less than 27 years old). Still, the team flailed considerably, evidenced by A.L. season lows in categories such as team batting average and runs scored (one of the few categories in which they did lead the league was with errors—138—33 more than the league average). Maroth’s scant nine wins led the Tigers staff, but he might have avoided the sizable number of losses if he had garnered more offensive support—in 14 of the 21 losses, the team scored three or fewer runs.

Conversely, a 5.73 ERA—more than a run higher than the league average—did little to further his cause. Adding insult to injury, Maroth led he league in earned runs allowed, and shared the dubious distinction of most home runs allowed with two other hurlers. Amongst his 20-loss brethren in the entire history of baseball (including the years before 1920), Maroth has the fewest number of complete games pitched (1), and the highest total of home runs allowed per nine innings (1.6). With such homely numbers, the determination is that Maroth “deserved” the 20-loss season, and is therefore “inducted” herein.

Pedro Ramos, Minnesota Twins (1961)

San Luis Pinar del Rio saw its share of heavy fighting during the rebellion that ousted Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista.1 Although he never participated in the fighting, native son Pedro Ramos may have felt he’d had his own experience with combat “shell shock,” for over the course of three seasons, he would lead the American League in home runs allowed—and it was during one of these years that he also joined the ranks of the 20-loss season.

Pedro Ramos flirted with a 20-loss season often before reaching the inglorious threshold. While pitching for the lowly Washington Senators 1958–60, Ramos managed to twirl 18, 19, and 18 losses respectively. It apparently took the team’s relocation to Minnesota in 1961 for him to finally achieve 20 losses. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Ramos led the American League in losses over each of the referenced four seasons.

In joining his 20-loss brethren, Ramos shares two distinctions with Mike Maroth: he was the Opening Day starter for his team in 1961 and he led the league in home runs allowed. Unlike Maroth, he set a pace for gopher balls that far outdistanced the second-place finisher, Gene Conley (39–33).

Ironically, two potential scenarios that did not come to fruition might have prevented Ramos from reaching 20-losses in 1961.

The 18-loss season that Ramos endured in the preceding season could be blamed in large part on the lack of offensive support he received from his teammates. Ramos produced a nice 3.45 ERA in 1960 (league average: 3.87), while his team could only muster an average of less than 1.5 runs per game in 15 of his 18 losses. Frustration finally boiled over, and he “demanded to be traded to another club, preferably the Yankees.”2 One can only surmise that had such a trade occurred, and Ramos found himself pitching for the power-laden offense that included Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris, he would not have attained the 20-loss threshold the following season (no matter how many gopher balls he served up).

On a completely separate front, Ramos and his fellow native Cubans nearly sat out the entire 1961 season. After the Cuban rebellion, the International League withdrew its Havana franchise, and in the latter part of 1960 there was much speculation that, in retaliation, “Fidel Castro won’t let Cuban players come to the United States [in 1961].”3 Obviously, had Castro delivered on this perceived threat and prevented the Cuban players from playing in 1961, Ramos would not have been around to twirl his 20 losses.

But play he did, and not for the Yankees. His ERA would increase by an additional one-half run, and he would lead the league in base hits allowed, while serving up the aforementioned league-leading 39 home runs. Such ugly numbers “award” Ramos the distinction of joining Mike Maroth in induction to the “deserving” category.

“Honorable” Mention: Don Larsen, Baltimore Orioles (1954)

Far more famous for being the only pitcher to ever twirl a perfect game in World Series competition, two years earlier Larsen was a part of the humble franchise that relocated from St. Louis to Baltimore in 1954. A team in the midst of 14 consecutive non-winning campaigns (they would manage to secure a .500 season in 1957), the move to Maryland did little to turn their fate around, as the team would lose 100 games for the second straight season.

An anemic offense contributed to the malaise, as the club garnered only 52 home runs team-wide through the 1954 season (a mere three more than the N.L. champion Ted Kluszewski’s 49 dingers the same year). Larsen could arguably be slotted in the “Unjustified” category due to this lack of offensive support. Fairly or not, he is slotted here for the unique record he holds among the roster of 20-loss pitchers: Larsen’s .125 winning percentage (3–21) is the lowest mark registered for the period researched from 1920 forward, and eighth lowest all-time.

Unlike the fate that befell Pedro Ramos, Larsen would be traded to the New York Yankees at the conclusion of the 1954 season, and attain a certain level of success over five seasons that included the aforementioned perfect game. Then, on December 11, 1959, Larsen would be traded once more, to the Kansas City Athletics, where he would again post an incredibly low winning percentage during the 1960 season: .091 (1–10).

Thus, for attaining the lowest winning percentage in modern major league history—with a sizable assist from his teammates’ feeble offensive skills—Larsen’s 20-loss season places him in the “deserved” category.

There are certainly many other pitchers who could conceivably belong in this problematic grouping with Messrs. Maroth, Ramos, and Larsen, but some of these have carved out a category all to themselves.

THE REPEAT OFFENDERS

The all-time list is extensive, and includes such notables as Cy Young and Walter Johnson, as well as Pud Galvin, Tim Keefe, and Old Hoss Radbourne (each a HOF inductee). The period from 1920 forward includes its own share of HOF notables, such as Phil Niekro, Ted Lyons, Red Ruffing, and Eppa Rixey. The category that captures such worthy hurlers is that of “The Repeat Offenders,” defined as those who have, on more than one occasion, lost 20 or more games in a single season. There are 17 such pitchers since 1920 (three of whom actually span the period from 1917–25), not all of whom stand out as prominently as the HOF inductees above, but many of these have an interesting back-story all the same.

Phil Niekro, Atlanta Braves (1977, 1979)

Wilbur Wood, Chicago White Sox (1973, 1975)

Excluding the remarkable season that lefty Mickey Lolich had with the Detroit Tigers in 1971—45 games started, while completing 29 of those—it is not surprising that Phil Niekro and Wilbur Wood are the only pitchers since 1923 to take the mound in a starting role 43 or more times in a single season (in large part due to the lack of arm strain sustained by a knuckleball hurler). In so doing, both former 20-game winners (on numerous occasions) also posted two 20-game losing seasons while pitching for their respective sub-.500 clubs. In fact, during a four-year stretch in each of their careers (Niekro, 1976–79; Wood, 1971–74), each would personally account for over 27 percent of his team’s total victories. With these similar characteristics, Niekro and Wood are consigned together in the “Repeat Offenders” category.

Much as a knuckleball is baffling to a hitter, the two 20-loss campaigns that Niekro posted appear just as mystifying. Niekro accumulated these two seasons while pitching for a dreadful Braves team that finished last in the N.L.’s Western Division four years in a row. One such season was accompanied by 21 wins, truly an amazing win total considering the fact that he led or tied the league lead in some rather dubious categories—41 home runs allowed, 113 walks allowed, 311 hits allowed, and 11 hit batsmen (Niekro would also rank second to Vida Blue in earned runs allowed). Conversely, the other, more “deserving” 20-loss season (an ERA that rose to a non-career-like 4.03) saw Niekro lead the league in some of the same dubious categories—although yielding a much lower (26) home run total—while winning five fewer games. Taken all together, it appears that a combination of pitching for a poor-performing team, and a tendency toward yielding the gopher ball (Niekro is fourth all-time in career home runs allowed) provide the ingredients necessary for this Hall of Fame inductee to also find entry into the “Repeat Offenders.”

Unlike Niekro, fellow knuckler Wilbur Wood did not pitch for a last-place team during his 20 loss seasons—though it was often very close. In the two 20-loss campaigns (Wood was one 1974 loss shy of three consecutive 20-loss seasons) the White Sox finished fifth in a six-team division. Like his fellow knuckler, pitching for a poor-performing cast contributed mightily to one of the two 20-loss seasons, as his teammates could muster a total of only 18 runs in 15 of those 20 losses. Still further evidence that these two should be forever linked in the “Repeat Offender” category is their remarkably similar statistical lines during each of their 20-loss seasons:

| W-L | ERA | W-L | ERA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wilbur Wood | 24–20 | 3.46 | and | 16–20 | 4.11 |

| Phil Niekro | 21–20 | 3.39 | and | 16–20 | 4.03 |

Still, these two do not stand alone in common pairing, as evidenced by the following:

Paul Derringer, St. Louis Cardinals and Cincinnati Reds (1933); Cincinnati Reds (1934)

Red Ruffing, Boston Red Sox (1928, 1929)

Bump Hadley, Chicago White Sox and St. Louis Browns (1932); St. Louis Browns (1933)

Roger Craig, New York Mets (1962–63)

It is remarkable to lose 20 games in each of two separate seasons. What may be even more noteworthy is to have done so in consecutive years, for that is exactly what Messrs. Derringer, Ruffing, Hadley, and Craig achieved. Even more extraordinary is the fact that two of these four pitchers would, at an early stage in their careers, lose at least 47 games over the course of two campaigns and still go on to earn Hall of Fame consideration (and, in one instance, induction).

Few players have launched their major-league careers as successfully as Paul Derringer did in 1931—leading the N.L. with a .692 winning percentage (18–8) while helping the St. Louis Cardinals to a World Championship. Unfortunately, the team would plummet to a second division finish the following season, and Derringer’s sophomore year followed suit (11–14, 4.05 ERA). A rocky start in 1933 precipitated a multi-player trade that sent Derringer to the Cincinnati Reds, a fate that foretold the two consecutive 20-loss seasons, as the Reds were in the midst of a nine-year drought that included five last-place finishes.

Arriving in Cincinnati with an 0–2 mark, Derringer went on to lose an additional 25 games—one has to go back to 1905 to find a pitcher with more than 27 losses in a single season—followed by 21 losses in 1934. Amazingly, Derringer accumulated these losses with ERAs of 3.30 and 3.59 in 1933 and 1934, respectively (while allowing an incredibly low four home runs in 1933). The anemic Cincinnati offense tells the entire picture, as it managed only 25 runs in 30 of the 48 total losses Derringer sustained over that two-year period. Fortunately, Derringer’s (and the Reds’ fate overall) would take a more positive turn, and he would go on to garner MVP consideration in five of the next six seasons. Derringer’s later success notwithstanding, the 1933–34 campaigns serve to earn him consideration in the “Repeat Offenders” category.

Derringer’s counterpart in regard to receiving Hall of Fame consideration (and, in this instance, induction) is Red Ruffing. A 39–93 career mark at the age of 24 would hardly seem conducive to such a later honor. Ruffing accumulated 25 and 22 losses in 1928 and 1929 seasons, respectively. Similarities to Derringer do not end with HOF consideration though, for much as Derringer struggled with some very bad Cincinnati clubs, Ruffing would pitched for some incredibly horrible Boston Red Sox teams.

The angst of January 3, 1920, is considerably lessened by the 2004 and 2007 championship seasons, but it is still capable of invoking the wrath of Red Sox’ fans worldwide. That was the day Babe Ruth was sold to the New York Yankees, and the sale contributed largely to the franchise’s tailspin over the following 14 seasons. Ruffing joined the Sox in the teeth of this long descent, and a league-low team batting average for nine consecutive seasons (1922–30) contributed to the lack of offensive support that garnered Ruffing 25 and 22 losses. Not discounting the fact that 20 losses for any pitcher is often the result of a certain team-wide ineptitude, Ruffing did not help his cause when leading the league in earned runs surrendered during both the 1928 and 1929 campaigns.

While the Red Sox would continue a slow crawl out of perpetual second-division league occupancy (including last-place finishes in nine of 11 consecutive seasons), Ruffing would be spared a portion of this fate when traded to the New York Yankees early in the 1930 season. The trade would contribute largely to the resurrection of Ruffing’s career, as he would go on to win an average of more than 16 games over the course of 13 seasons, including four consecutive 20-win campaigns. Still, just as Ruffing’s latter success mirrors Derringer’s as far as helping to turn his career around, the two 20-loss campaigns of Ruffing serve as induction as a “Repeat Offender” as well.

Roger Craig never attained the success that Messrs. Derringer and Ruffing achieved, ending his career with only a .430 winning percentage. Nearly 50 percent of his career 98 losses was accumulated while pitching two seasons for the hapless expansion New York Mets, and perhaps one name more than any other illustrates the frustration Craig experienced in two consecutive 20-loss seasons: Roy Sievers!

On July 19, 1963, Craig took the mound in Connie Mack Stadium against the Philadelphia Phillies sporting a 2–15 record. Having lost 24 games in the Mets’ inaugural season the year before, Craig was well on his way to two consecutive 20-loss seasons. But the 15 losses did not tell the whole story of Craig’s valiant efforts coming into this game, as seven of those losses were games where he gave up only eight earned runs combined! On this night, the 33-year-old righty was working on a masterful three-hit shutout when, with one out into the ninth, Phillies’ left fielder Tony Gonzalez hit a triple to right, followed promptly by a Roy Sievers home run that resulted in a heartbreaking 2–1 loss for Craig.

Sadly, Craig’s demise at the hands of Sievers was not limited to this game alone. A month and a day later, Craig took the very same mound and again threw goose eggs into the ninth. With two outs, Sievers stepped to the plate and deposited the fourth pitch he saw into the stands to tie the game (from which the Phillies prevailed in extra innings).

These two games seem to capture the essence of what it was like to play for the Mets during Craig’s two-year stretch: not enough offense (last in team batting average), a porous defense (most unearned runs allowed), and an unreliable pitching staff (last in team earned run average). “Can’t anybody here play this game?” lamented Manager Casey Stengel, but as evidenced by the games cited above, another Stengelese quotation seems more appropriate to Roger Craig: “You make your own luck. Some people have bad luck all their lives.”

Yet if bad luck can be defined as being unfortunate enough to be traded from a contending team to a near-perennial cellar-dweller, then Bump Hadley is as unlucky a pitcher as Casey Stengel might have ever encountered. Hadley began his major-league career with the then-successful Washington Senators—a unique phrase if ever there was one—and posted a respectable 58–56 record over the course of five seasons. A sequence of two trades in less than five months would place Hadley into the starting rotation for the lowly St. Louis Browns, where a far less successful 38–56 mark would be sustained over three long campaigns—including consecutive 20-loss seasons, 1932–33.

Not that Hadley seemed to be helping his own cause, as over the course of these two consecutive 20-loss endeavors, he would uncharacteristically lead the American League in both earned runs and walks allowed (marks that would surely make Hadley eligible for the “Deserved” category). Yet, unlike “Deserved” Pedro Ramos, who unsuccessfully sought to be traded to the power-laden Yankees, Hadley found himself with the Bronx Bombers toward the end of his career. During this five-year stint, Hadley would again post respectable numbers (49–31) to complement his earlier success with the Senators.

Ironically, Hadley would post two of the four consecutive 20-loss seasons sustained by Browns’ pitchers between the years 1931–34. The mantle of continuity would be raised by a pitcher who, since 1920, stands alone in the “Repeat Offender” category.

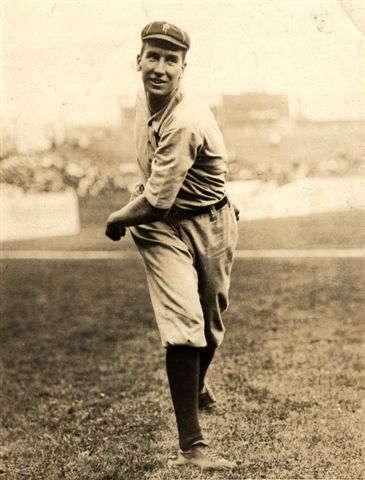

Bobo Newsom, St. Louis Browns (1934); Detroit Tigers (1941); Philadelphia Athletics (1945)

A tall righty from Hartsville, South Carolina, Bobo Newsom pitched 20 years in major-league ball while logging time with nine different franchises. Jumping into the big leagues permanently in 1934 (after posting a 30-win season the year before with Los Angeles of the Pacific Coast League), Newsom would experience three 20-loss seasons, while coming remarkably close to losing 20 games in at least two additional years. Thrice a 20-game winner (and a four-time American League All-Star), the combined 60 losses over three seasons accounted for over 27 percent of Newsom’s career total of 222 losses.

A tall righty from Hartsville, South Carolina, Bobo Newsom pitched 20 years in major-league ball while logging time with nine different franchises. Jumping into the big leagues permanently in 1934 (after posting a 30-win season the year before with Los Angeles of the Pacific Coast League), Newsom would experience three 20-loss seasons, while coming remarkably close to losing 20 games in at least two additional years. Thrice a 20-game winner (and a four-time American League All-Star), the combined 60 losses over three seasons accounted for over 27 percent of Newsom’s career total of 222 losses.

Newsom didn’t waste any time accumulating his first 20-loss season. St. Louis Browns’ manager Rogers Hornsby inserted Newsom into the starting rotation in his first full season—he’d made six appearances with two teams over the course of four years prior to his rookie campaign with the Browns—and he responded favorably, leading the team in wins, ERA, complete games, saves, strikeouts, and innings pitched. Unfortunately, twirling for a pitiful Browns’ club, he also led the entire American League in losses with his first 20-loss campaign. Subsequent 20-loss seasons would mirror Newsom’s rookie endeavor, as he would be among the team leaders in some of the very same categories while pitching for the Detroit Tigers and Philadelphia A’s in 1941 and 1945, respectively.

The most remarkable aspect herein is how close Newsom came to two additional 20-loss seasons. In his sophomore endeavor, Newsom opened the season with an 0–6 mark when he was sold by the Browns to the similarly inept Washington Senators. Newsom would go on to post a respectable 11–12 mark with the Senators, for an accumulation of 18 losses for the entire season. Yet, that does not tell the whole story: Newsom missed the entire month of June, resulting in an estimated eight fewer opportunities to have lost two additional games, enough to have attained a fourth 20-loss endeavor.

Then, in 1942, Newsom found himself back with the Senators after a 20-loss campaign with the Detroit Tigers the year before. By August 23, Newsom stood at 17 losses with more than a month to go to attain 20. A week later, Newsom would be sold to the pennant contending Brooklyn Dodgers where he would fall one loss short of the “coveted” 20-loss campaign. One is left to speculate that had Newsom remained with the second division Senators through the month of September, he might have accumulated the three additional losses necessary to attain a fourth 20-loss season.

For purposes of bringing closure to the “Repeat Offenders” category, the 10 remaining pitchers who posted at least two 20-loss campaigns since 1920 are below. Of distinct note are three pitchers who inexplicably garnered MVP consideration during these particular seasons:

| Pitcher | Team | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Eppa Rixey | Philadelphia Phillies | 1917, 1920 |

| Jesse Barnes^ | Boston Braves | 1917, 1924 |

| Sad Sam Jones | Boston Red Sox | 1919 |

| New York Yankees | 1925 | |

| Jack Scott | Boston Braves | 1920 |

| Philadelphia Phillies | 1927 | |

| Slim Harriss | Philadelphia A’s | 1922 |

| Boston Red Sox | 1927* | |

| Ted Lyons | Chicago White Sox | 1929, 1933 |

| Hugh Mulcahy | Philadelphia Phillies | 1938*, 1940* |

| Murry Dickson+ | Pittsburgh Pirates | 1952* |

| Philadelphia Phillies | 1954 | |

| Al Jackson | New York Mets | 1962, 1965 |

| Dick Ellsworth | Chicago Cubs | 1962, 1966 |

* garnered MVP consideration; BOLD indicates a Hall of Fame inductee.

^ Barnes holds a unique distinction among his 20-loss brethren—losing 20 games for the same team twice, while hurling for another club in between.

+ Dickson’s removal from the starting rotation after August 25 likely spared him a third 20-loss campaign in 1953. Had he done so, it would have qualified him as the only pitcher since 1907 with three consecutive such seasons, when Irv Young last accomplished this feat while pitching for the Boston Beaneaters/Doves (Kaiser Wilhelm posted a major-league career three-peat in 1908, but his streak was interrupted by two minor-league campaigns in 1906–07). Overall, there have been 34 pitchers who have posted a 20-loss three-peat, most of whom did so in the 19th century—including 10 consecutive 20-loss seasons posted by Hall of Fame inductee Pud Galvin.

DR. JEKYLL and MR. HYDE

This category is reserved for those pitchers who, for one reason or another, managed to win 20 games in a particular season, only to turn around and lose 20 in the following campaign (or vice versa). Evidence provided of this about-face is symptomatic of such a Jekyll-and-Hyde performance, thereby capturing this unique designation.

Luis Tiant, Cleveland Indians (1968: 21–9, 1969: 9–20)

The year 1968 would be a watershed year for pitching, the dominance of which would result in a mere six major-league batters managing to achieve a meager .297 average, while seven hurlers posted an ERA of less than 2.00. Tiant was among that select few, capturing his first of two career American League ERA titles with a minuscule 1.60 (barely edging out teammate Sam McDowell’s 1.81), while also pacing the league in shutouts with nine. Tiant posted a deceptive 21–9 record which could easily have been enhanced with a little more offensive support, as he did not reckon in three decisions where he pitched a total of 19 innings while giving up a collective eight hits and two runs. With such sterling numbers, it is remarkable to realize that, although Tiant secured Cy Young Award consideration three separate times throughout his career, 1968 was not one of those occasions. Denny McLain’s 31-victory year had much to do with that.

The anemic offensive output in the major leagues overall ushered in a number of rule changes for the following 1969 season—a smaller strike zone and a reduced mound height. These new rules brought about the desired effect, as the major leagues witnessed a spike of nearly 20 percent more runs scored per game. Tiant’s numbers suffered accordingly, as he would lead the major leagues in such dubious categories as home runs and walks allowed, while tying the major-league mark for losses with 20. Although it is easy to blame this about-face on the newly implemented rule changes, no other pitcher suffered such a dramatic turnaround, thereby granting the anointment of Tiant as an inductee to the Jekyll-and-Hyde category.

Dick Ellsworth, Chicago Cubs (1962: 9–20, 1963: 22–10)

On September 2, 1963, a ground-ball out induced by Chicago Cubs closer Lindy McDaniel resulted in the final out of a 7–5 victory for the visiting team, insuring McDaniel’s teammate Dick Ellsworth a 20th win (the first such season for a Cubs hurler since 1945). Ellsworth would go on to post a career-high 22 victories and a second-place finish in pursuit of the ERA crown (2.11), while pacing the Cubs to their first winning season in 17 years—an 82–80 mark that still resulted in a poor seventh-place finish. This overall success—meager as it was—was largely attributable to the efforts emanating from the mound, as the pitching rotation witnessed a dramatic turnaround from the prior season. Spared a last place ranking for team ERA by the expansion New York Mets in 1962, the Cubs would post a second-best team ERA of 3.08 during the following season.

Yet pitching was not often a source of pride for this Windy City bunch, and the team could again be thankful for the existence of the newly inducted New York Mets in sparing them a last place finish in 1962 while chalking up 103 losses (Mets: 120 losses). Again, Ellsworth would pace the team, though this time in a losing effort with a team-high 20 losses (incidentally, Ellsworth and teammate Don Cardwell joined the roster of top nine pitchers for the most losses in the National League in 1962, while the remaining seven came from the two expansion teams—the Mets and the Houston Colt .45s). Furthermore, if Ellsworth name appears familiar, he was included in the roll call of “Repeat Offenders” when he added a 22 loss season to his Cubs resume during the 1966 campaign. Still, the 20 loss/22 win seasons of 1962–63 respectively earn Ellsworth induction into the category of “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.”

Steve Carlton (1972: 27–10, 1973: 13–20)

When one examines Carlton’s 27 wins in 1972 vs. his 20 losses in 1973, one question arises: how could he possibly win 27 games? Carlton toiled for the last place Philadelphia Phillies during this Jekyll-and-Hyde phase of his career, producing a herculean effort from the slab. Incredibly, the 27 wins tell only part of the story, as his teammates could marshal only seven runs in eight outings where he did not figure in the win—a smattering of runs in even half of those eight games might have ushered Carlton into the select company of pitchers who’ve reached the 30-win threshold. A sterling 1.97 ERA was accompanied by 310 strikeouts—a figure reached by only five other pitchers since 1972—and a major-league leading 30 complete games. The 27 victories made up an astonishing 46 percent of the club’s total of 59 wins. Such numbers resulted in the first of four career Cy Young Awards, while also garnering Carlton MVP consideration.

The 1973 season saw Carlton return to mere mortal status as his ERA rose to 3.90 (not far removed from the major-league average of 3.75) while leading the staff in games started (40), complete games (18), and strikeouts (223). Although Carlton’s overall stats were decidedly different, the Phillies’ offensive malaise remained intact (even though the lineup featured major components of the 1980 Championship team—specifically Mike Schmidt, Greg Luzinski, Bob Boone and Larry Bowa), exemplified by the fact that in 14 of Carlton’s 20 losses, the Phils were only capable of mustering a total of 12 runs! Arguably, this lack of offensive support could easily qualify “Lefty” for the “Unjustified” category, but other qualified candidates have relegated this Hall of Famer to “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” instead.

Before considering the next group, the following reflects all other pitchers who have had a 20-win/20-loss season (or vice versa) in consecutive years. Some we’ve seen already, others who will be seen again:

20 WIN / 20 LOSS SEASONS

| Pitcher | Team | Year | Record |

|---|---|---|---|

| Joe Oeschger | Boston Braves | 1921 | 20–14 |

| 1922 | 6–21 | ||

| Bobo Newsom | Detroit Tigers | 1940 | 21–5 |

| 1941 | 12–20 | ||

| Alex Kellner* | Philadelphia Athletics | 1949 | 20–12 |

| 1950 | 8–20 | ||

| Murry Dickson | Pittsburgh Pirates | 1951 | 20–16 |

| 1952 | 14–21 | ||

| Larry Jackson | Chicago Cubs | 1964 | 24–11 |

| 1965 | 14–21 | ||

| Mel Stottlemyre | New York Yankees | 1965 | 20–9 |

| 1966 | 12–20 | ||

| Stan Bahnsen | Chicago White Sox | 1972 | 21–16 |

| 1973 | 18–21 | ||

| Wilbur Wood | Chicago White Sox | 1972 | 24–17 |

| 1973 | 24–20 | ||

| 1974 | 20–19 | ||

| 1975 | 16–20 | ||

| Jerry Koosman | New York Mets | 1976 | 21–10 |

| 1977 | 8–20 |

* Kellner’s 20-win performance was posted during his rookie year, but he fell short of the Rookie of the Year Award when placing second to Roy Sievers (he of the aforementioned Roger Craig infamy). Although his career would stretch another nine seasons, Kellner would never repeat the success of his debut outing.

20 LOSS / 20 WIN SEASONS

| Pitcher | Team | Year | Record |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eddie Rommel | Philadelphia Athletics | 1921 | 16–23 |

| 1922 | 27–13 | ||

| Dolf Luque | Cincinnati Reds | 1922 | 13–23 |

| 1923 | 27–8 | ||

| Ted Lyons | Chicago White Sox | 1929 | 14–20 |

| 1930 | 22–15 | ||

| Paul Derringer* | Cincinnati Reds | 1933 | 7–27 |

| Total—STL/CIN | 1934 | 15–21 | |

| 1935 | 22–13 | ||

| Randy Jones+ | San Diego Padres | 1974 | 8–22 |

| 1975 | 20–12 | ||

| 1976 | 22–14 |

BOLD indicates a Hall of Fame inductee

* Derringer is the only pitcher since 1920 to have a 20-win season preceded by two consecutive 20-loss campaigns.

+ Jones is the only pitcher since 1920 to have two consecutive 20-win campaigns on the heels of a 20-loss season.

THE UNJUSTIFIED

Of the 97 20-loss campaigns since 1920, nearly one-third (31) were hurled by a pitcher whose earned run average was less than either the circuit or major-league average (and often both) for a particular season—going a long way toward explaining why a team would trot their pitcher out so frequently while the losses continued to accumulate. As the term implies, this category attempts to capture the stories of those pitchers who, while posting better-than-average numbers, unjustly accumulated 20 losses. Much like Carlton, Niekro, and others aforementioned, these pitchers were all victims of anemic run support, making it seemingly impossible to avoid the debit ledger. For example:

Jerry Koosman, New York Mets

(1977: 8–20, 3.49 NL/MLB avg: 3.91/4.00)

Deservedly, the 1962 expansion New York Mets are held up as one of the most inept teams in the history of the game, but they can claim at least one positive distinction: a slightly greater offensive output than their 1977 counterpart:

| Category | 1962 Mets | 1977 Mets |

|---|---|---|

| Batting Average | 0.240 | 0.244 |

| Home Runs | 139 | 88 |

| Runs Scored | 617 | 587 |

It was in the midst of such offensive malaise that Jerry Koosman took the mound 32 times, giving up more than four earned runs on only four of those occasions. His meager eight wins would, sadly for the team as a whole, be among the team’s top three season leaders. Adding insult to injury, the Mets offense would muster only 19 runs scored in 16 of the 20 losses. Little did he know that this production would appear like an offensive avalanche to the next pitcher on our list.

Phil Niekro, Atlanta Braves 1979

21–20, 3.39 NL/MLB avg: 3.73/4.00 HR allowed: 41

Pedro Ramos, Minnesota Twins 1961

11–20, 3.95 AL/MLB avg: 4.02/4.03 HR allowed: 39

NOTE: he of the aforementioned “Deserved” category is included here amongst this unique niche.

Murry Dickson, Pittsburgh Pirates 1952

14–21, 3.57 NL/MLB avg: 3.73/3.70 HR allowed: 26

Eddie Rommel, Philadelphia Athletics 1921

16–23, 3.94 AL/MLB avg: 4.28/4.03 HR allowed: 21

As unique as this niche may be, there were other pitchers (or groups of same) who carved their own indelible mark.

MISCELLANEOUS

Perhaps no 20-loss profile would be complete without identifying the two pitchers who lost 20 in a season and never wore a major-league uniform again.

| Pitcher | Team | Year | Record |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dick Barrett | Philadelphia Phillies | 1945 | 8-20 |

| Gordon Rhodes | Philadelphia A’s | 1936 | 9-20 |

Relegated to the minors in 1946 and 1937 respectively, neither Barrett nor Rhodes (with a combined total of 13 years in the major leagues) would ever see another opportunity to return.

They nearly were joined in this unique group by Roy Wilkinson (4–20; Chicago White Sox, 1921), but a mere four appearances in 1922 separates him from this pair. Still, Wilkinson, along with Joe Oeschger (6–21; Boston Braves, 1922) managed to carve their own special place in the archives: as the only pitchers to lose 20 while starting so few games—23! [Spoiler alert: they both sustained many of the losses coming out of the bullpen.]

In a complete reversal to the fortunes of Barrett and Rhodes are the two pitchers who accompany Bobo Newsom by entering the major leagues with a 20-loss campaign:

| Pitcher | Team | Year | Record |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clay Kirby | San Diego Padres | 1969 | 7-20 |

| Bill Wight | Chicago White Sox | 1948 | 9-20 |

Then there is the 20-loss campaign disguised as the sophomore jinx. In a case eerily similar to that which befell Alex Kellner a mere three years earlier, Harry Byrd did secure Rookie of the Year honors after the 1952 campaign, only to fall to 11–20, 5.51 ERA in his follow-up endeavor. Ultimately he bounced between five different clubs in hopes of regaining his debut success, but was relegated to the minor leagues in 1957 from which he never returned.

Lastly is the statistical blurb of Pat Caraway (10–24; Chicago White Sox, 1931). Accompanied by a 6.22 ERA, Caraway holds the dubious distinction of maintaining the highest earned run average in the 20th Century among his 20-loss brethren.

THE TEAMMATES (and other additional TEAM-WIDE analyses)

There have been only 97 20-loss campaigns since 1920. What is of particular note is that, in more than 15 percent of those instances, that pitcher had a teammate putting up similar numbers in the loss column:

| Year | Team | Pitcher | Record |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1973 | Chicago White Sox | Wilbur Wood | 24–20 |

| Stan Bahnsen | 18–21 | ||

| 1965 | New York Mets | Jack Fisher | 8–24 |

| Al Jackson | 8–20 | ||

| 1962 | New York Mets | Roger Craig | 10–24 |

| Al Jackson | 8–20 | ||

| 1936 | Philadelphia Phillies | Bucky Walters | 11–21 |

| Joe Bowman | 9–20 | ||

| 1934 | Cincinnati Reds | Si Johnson | 7–22 |

| Paul Derringer | 15–21 | ||

| 1930 | Boston Red Sox | Milt Gaston | 13–20 |

| Jack Russell | 9–20 | ||

| 1920 | Boston Braves | Jack Scott | 10–21 |

| Dana Fillingim | 12–21 | ||

| 1920 | Philadelphia Athletics | Scott Perry | 11–25 |

| Rollie Naylor | 10–23 |

To even the casual observer between 1920 and 1945, Philadelphia could often be a brutal city in which to follow baseball (particularly when owner/manager Connie Mack was in the midst of one of his many iterations of “house-cleaning” associated with the Athletics). This seemed doubly so when it came to the 20-loss campaign, as the Phillies or their other-league counterpart would make it a semi-regular practice.

To even the casual observer between 1920 and 1945, Philadelphia could often be a brutal city in which to follow baseball (particularly when owner/manager Connie Mack was in the midst of one of his many iterations of “house-cleaning” associated with the Athletics). This seemed doubly so when it came to the 20-loss campaign, as the Phillies or their other-league counterpart would make it a semi-regular practice.

For example, when Perry and Naylor posted their 20-loss efforts jointly, Phillies pitcher Eppa Rixey posted his own 11–22 mark. A year later, in 1921, Eddie Rommel would lose 23 games for the Athletics, and the Phillies George Smith matched him with a 4–20 record.

When in 1936 teammates Walters and Bowman accounted for 41 losses between them, the A’s were able to counter with their own Gordon Rhodes (whom we visited earlier). Then in 1945, in lieu of actual teammates, these two franchises that shared the same Shibe Park (later named Connie Mack Stadium) would each have a pitcher who shared the same 8–20 mark—Bobo Newsom, A’s; Dick Barrett, Phillies.

It almost goes without saying, but since 1920 these two franchises—one of which residing in Oakland these many years—outpace all others in the number of 20-loss campaigns by one of their hurlers to this day:

- 14: PHI/KC/OAK Athletics

- 13: Philadelphia Phillies

- 10: BOS/MIL/ATL Braves

- 9: Chicago White Sox

CONCLUSION

The 20-loss season has been visited upon a vast gamut of pitchers—from the youngster ushered thereafter out of baseball, to the eventual Hall of Fame inductee. Besides just “getting there,” many of these hurlers had an interesting sidebar in reaching that dubious threshold, a sidebar worth the telling.

It bears repeating that at no point herein was there intent to denigrate or belittle the accomplishments of the pitchers cited. In fact, just the opposite, as the author found a whole new appreciation of many of these pitchers—Wilbur Wood or Bobo Newsom, for example—while researching this material.

Still, if this extensive profile accomplishes nothing else, it is the desire that these 20-loss campaigns, seemingly forgotten in the midst of other (sexier?) statistical endeavors, are not consigned to the waste bin of time.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to thank Bill Nowlin for both his assistance and encouragement to this endeavor. Further thanks is extended to Clifford Blau for his diligence in fact-checking the narrative.

DAVID E. SKELTON developed a passion for baseball early on when the lights from Philadelphia’s Connie Mack Stadium would shine through his bedroom window. Long since removed from Philly, he now resides with his family in central Texas but remains passionate about the sport that evokes many of his earliest childhood memories. Employed for over 30 years in the oil and gas industry, he became a SABR member in early 2012 after a chance—and most fortunate—holiday encounter with a Rogers Hornsby Chapter member. Researching Dick Ellsworth for SABR’s BioProject led to the peculiar findings that occasioned the article herein.

Sources

www.baseball-vault.com/casey-stengel-quotes.html

Notes

1 “Rollicking Ramos No Joke to Swatters,” The Sporting News, May 3, 1961.

2 “Pedro Wins Spurs as One-Half of Nat Sunday Slab Punch,” The Sporting News, June 1, 1960.

3 “Will Castro Bar Cubans From Playing in U.S.?,” The Sporting News, October 12, 1960.