A Ballpark Opens and A Ballplayer Dies: The Converging Fates of Shibe Park and “Doc” Powers

This article was written by Robert D. Warrington

This article was published in Fall 2014 Baseball Research Journal

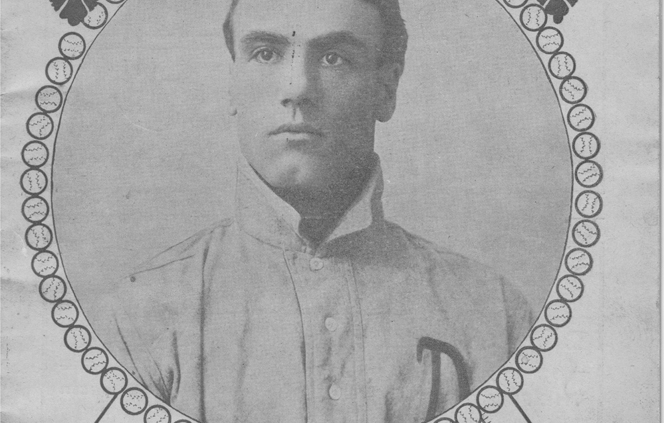

This story tells the tragic tale of Michael “Doc” Powers, a catcher who played primarily for the Philadelphia Athletics and whose baseball career was cut short by his untimely death. Misconceptions about what caused his demise abound, but can be laid to rest by this article. Ultimately, “Doc Powers Day” was organized by the American League and hosted by the A’s to raise funds for his widow and children, an extraordinary effort for its time.

A Real Doctor

Michael Riley Powers was born in Pittsfield, Massachusetts on September 22, 1870.1 Unlike the majority of baseball players called “Doc,” he earned the nickname legitimately. After graduating from the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, and the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana, Powers completed his medical studies at Louisville Medical College while playing for the Louisville Colonels. After arriving in Philadelphia, he passed the State Board examination for doctors in Pennsylvania. Powers practiced medicine each offseason at an established medical practice in Jeffersonville—a community located northwest of Philadelphia—where he lived with his wife, Florence, and three children.2 Using his medical skills, Powers often treated teammates for minor injuries, also gaining the nickname “Red Cross Mike.”3

Baseball Career

Powers played college baseball at Holy Cross and Notre Dame.4 He made his major league debut on June 12, 1898, with the Louisville Colonels of the National League.5 Powers was used sparingly by the Colonels, appearing in just 34 and 49 games, respectively, 1898–99. He was sold to the Washington Senators on September 16, 1899, and played in 14 games for the Senators at the tail end of the season.

In March 1900 the NL jettisoned what it judged to be weaker franchises: Louisville, Baltimore, Cleveland, and Washington.6 Like many other players, Powers found himself without a job and migrated to the newly-named American League of Professional Baseball Clubs—formerly known as the Western League— which was categorized as a minor league circuit at that time.7 He became the Indianapolis Hoosiers’ full-time catcher, appearing in 110 games for a team that finished in third place.

During the 1900–01 offseason, American League president Ban Johnson sought equal standing with the NL. Achieving this end meant changing the geographic configuration of the league, again dropping less robust franchises and establishing new ones in the east. AL teams in Chicago, Milwaukee, Detroit, and Cleveland were kept, while Indianapolis, Kansas City, Buffalo, and Minneapolis were replaced by clubs in Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington—cities with populations large enough and locations favorable enough to enable the AL to compete head-to-head with the NL.8

“Doc” Powers became a player without a team for a second time. Connie Mack was selected to manage the AL’s Philadelphia club, which chose the nickname Athletics because of its long and honored place in the city’s baseball history.9 Mack scrambled to put together a roster in time for the 1901 season, and he signed several players who were still under league control even though their clubs had been eliminated. Powers then stayed on the A’s roster—with one brief interlude—for the rest of his professional baseball career.10

Powers was a light hitter at the plate and ponderous on the bases, but he had a cannon for an arm and possessed considerable prowess in handling pitchers. David Jordan writes in his history of the Philadelphia Athletics that Powers was “a man who could keep his pitchers’ heads in the game.”11 Sportswriter George Graham, who covered baseball in Philadelphia when Powers played, wrote:

Powers was always a far better catcher than he was credited with being. He wasn’t much of a hitter—one of the poorest in the league, in fact—and he was painfully slow on the bases, but behind the bat he was alert-minded, he handled the mitt well and had a great arm.12

In 539 games over nine years with the A’s, Powers notched a modest .213 batting average with only three home runs. But Powers brought two assets integral to success as a catcher—a canny baseball mind and savvy baseball instincts. George M. Young, a Philadelphia sportswriter who reported on Powers during his time with the Athletics, observed:

A brainy catcher is the guiding genius of a team… It is usually the catcher who gives the delivery signals to the pitcher and also tips off the pitcher when to throw to bases. Also, it is he who places the men in the field to play for a particular batsman…Such a man was the late “Doc” Powers.13

Powers also served another key role as personal catcher to Eddie Plank—one of the greatest left-handed pitchers in baseball history. Mack recognized that when a catcher and pitcher develop a rapport, to maximize the effectiveness and comfort level of the pitcher they should be kept together. He used this formula with the brilliant yet madcap Rube Waddell. Ossee Schrecongost served as Waddell’s personal catcher—and roommate—for six years. Like Waddell, Schrecongost was an oddball with great fondness for alcohol.14

Powers caught 205 of Plank’s 282 starts, 1901–09.15 Plank presented challenges for any catcher, and the ability to handle him was a primary reason Powers remained with the team despite his anemic hitting.16 Sportswriter Stephen O. Gauley described the difficulties with Plank:

Perhaps Connie Mack and the rest of the Athletic rooters figured Powers’s greatest value to the team was in the fact that he was the only catcher who could successfully hold Eddie Plank’s puzzling delivery…“Doc” handled everything Plank could use without any apparent extra effort or trouble. Plank is not the easiest pitcher in the business to handle, as many a catcher who has tried it will testify, but Powers apparently reveled in Plank’s stubborn delivery. Crossfire “Doc” seemed to fairly eat up, and no matter how hard or low did some of Plank’s shoots go, Powers invariably mitted them, which other catchers would have let slip away to the grandstand.17

Connie Mack gave Powers the singular honor of catching the first game in club history on April 26, 1901, at the Athletics’ Columbia Park.18 Although the A’s came out on the short end of a 5–1 score against Washington, the team was off and running.19

Powers was the team’s primary catcher in 1901, then took a back seat to Schrecongost from 1902 through 1908. Schrecongost was a fine defensive catcher, with a lot more pop in his bat.20

The only brief interruption of this arrangement came during the 1905 season, when injuries left the New York Highlanders (also known as Yankees) needing a catcher on a temporary basis. Mack “loaned” Powers to the Highlanders for a short period of time. Although unheard of today, this practice was not uncommon during the early twentieth century, and no other clubs objected to this courtesy being extended. Powers joined New York on July 13, 1905. Remarkably, the Highlanders won 11 in a row with Powers on the roster and then a 12th after he returned to Philadelphia on August 7, 1905.21

Joy Tempered by Disquiet

After playing at Columbia Park for eight years, the Athletics moved to a new ballpark at the start of the 1909 season. Shibe Park became the club’s home for the rest of its stay in Philadelphia. The inaugural home opener occurred on Monday, April 12, 1909, with Plank pitching and Powers catching. The splendidly successful affair saw the A’s win over the Boston Red Sox, 8–1, before a sellout crowd in a ballpark that was the crown jewel of the league.22

The festive mood was diminished slightly by concern over the health of “Doc” Powers who had become ill during the game.23 One newspaper account reported:

The only thing that occurred to cast a shadow over the joy of the fans was the seizure of “Doc” Powers with acute gastritis in the seventh inning. The redoubtable catcher, however, refused to abandon his post behind the plate and though suffering intense agony, pluckily stuck to it until the end of the game. On the verge of collapse, he was taken to Northwest General Hospital where last night it was stated by the physicians attending him that he would probably be able to don a uniform again in a few days.24

Stories filed by reporters immediately after the ballgame were upbeat, with all estimating that Powers would be gone only a short time.25 Later that night, however, his condition worsened, and doctors judged it necessary to operate.26 The operation started at 1:00 am on Tuesday, April 13, and doctors discovered that Powers was suffering from intussusception.27

Intussusception, which happens rarely in adults, is a disorder in which part of the intestine slides telescopically into an adjacent part of the intestine, often preventing food or fluid from passing through and cutting off the blood supply to the blocked section.28 The lack of blood causes the tissue of the intestinal wall to die, which can result in perforation of the intestine and infection of the abdominal cavity—a life-threatening condition that requires immediate medical attention.29

The Death of “Doc” Powers

Surgeons found that the intussusception had caused more than a foot of intestine to become gangrenous, which they removed. Afterwards, “[Powers] was reported to be in a serious condition with even chances of recovery.”30 He rallied after the operation, which created optimism for several days that he would recover. A Sporting Life columnist observed, “The desperate operation at first bid fair to be successful.”31

The hope was short-lived. After a week, the abdominal pain and symptoms of obstruction recurred. A second, more intrusive operation was performed on April 20: Another blockage had formed and the gangrene had spread. Doctors cut out the blockage and infected area and created an artificial anus in the abdominal wall. For a brief period, Powers was able to eat food and showed other signs of recovery.32

But on the morning of Sunday, April 25, his condition again deteriorated. A third operation revealed he was experiencing acute dilatation of the heart.33 The prognosis was grim.34 Powers was given blood transfusions and oxygen, but doctors judged he was near death and wouldn’t live another day.35 Father Kinslow of Philadelphia’s St. Elizabeth’s Church was called to Northwest General Hospital on the morning of April 25 to administer the last sacrament. A newspaper reported, “At any minute [Powers] may be called upon to obey the mandate of the Inexorable Umpire, but He will find the noble athlete ready for the command.”36

Powers gamely held on throughout April 25, lapsing in and out of consciousness. At 9:14 on the morning of April 26, “Doc” Powers passed away. According to one newspaper account, Powers, who with his medical training knew of his impending doom, cried out just before dying, “I’ve got no pulse…no pulse!”37

What Killed “Doc” Powers?

Confusion existed at the time about what caused the death of Powers. Some of it was based on the initial misdiagnosis of his condition as acute gastritis and the forecast of a full recovery. The Philadelphia Inquirer acknowledged the “many conflicting reports” and to set the record straight, printed an explanation by one of the surgeons who assisted in the operations.38 The account is reproduced here in its entirety because it provides information important in refuting misconceptions that exist to this day about what killed the Athletics’ redoubtable catcher.

At the conclusion of the ball game on Monday, April 12, Powers was found to be suffering from interssusseption [sic]39 of the bowel, which can probably be better described in homely language as like the tuck put in a man’s shirt sleeve to shorten it when it is too long.

Interssusseption is a condition found most frequently in children and in individuals who have more or less gaseous intestinal distension, and can occur while peacefully lying in bed as readily as while strenuously exercising. The mortality is usually very high; it being regarded as a generally fatal condition.

The need for an operation on Powers was manifested by the fact that he had a mass in the right lower portion of his abdomen, giving excruciating pain, and the opening made into the abdomen over the site of the mass revealed the fact that the lower end of the small intestine had slipped into the colcum [sic] or upper end of the large intestine, rendering about fifteen inches of intestine devoid of blood supply by pressure, and consequent gangrene of this portion of the intestine.

Efforts to reduce this interssusseption or, in plainer language, to restore the intestine to its normal condition, were unavailing, and the fifteen inches of intestine involved were cut out and the ends of the severed intestine were united, with the result that the obstruction was removed and the patient’s symptoms for a week were such as to lead all to believe in his ultimate recovery. At this time, however, symptoms of obstruction recurred and it was found necessary to perform a second operation. An artificial anus was then established in the abdominal walls at the seat of the original operation, when the obstruction completely disappeared and the patient improved and partook of nourishment satisfactorily until Sunday morning, the 25th instant, when suddenly he developed acute dilatation of the heart with collapse. During the day a considerable quantity of liquid was introduced into his circulation directly through openings in his veins; oxygen was administered continuously, but under neither did he respond and death resulted at 9:14 am Monday.40

Intussusception—the disorder and medical complication arising from it—caused “Doc” Powers to die.41

Misconceptions about Powers’s Death

Despite credible, definitive explanations for cause of death—offered at the time of his death by attending physicians and separately by Northwest General Hospital—multiple misconceptions persist about what killed Powers.42 The two most prominent claims both stem from the day of April 12: either an injury suffered during the game or a sandwich—or sandwiches—Powers ate before or during the game.

The “sandwich” theory originates in newspaper articles written after the game but before surgery had revealed the true nature and extent of the malady. One article, for example, offered this account:

Powers ate a few sandwiches before the game, and these, with the undue excitement the “Doctor” labored under during the game, brought on the attack which did more to knock him out than any of the foul tips shot off the Bostons’ bats.43

The author of this piece did not cite a source for the “sandwiches” assertion.44 Another version of this claim read, “was said then to have been caused by a sandwich he ate while the game was in progress.”45 Still another contended the sandwich had “failed to digest properly.”46

Despite being fundamentally wrong, the sandwich theory probably formed in the fertile minds of reporters, conjuring a causative link between eating a sandwich and his subsequent ailment. Food poisoning is not mentioned explicitly by reporters, but the presumption may have seemed reasonable on a prima facie basis to the writers. Specifically:

- Powers ate a sandwich—perhaps several sandwiches—either before or during the game.47

- Some sources identify it as a cheese sandwich. It could have contained pathogens such as salmonella or listeria that cause food poisoning.48

- Foodborne illness—generically referred to as food poisoning—was one of the most common gastrointestinal ailments in America in 1909, as it remains to this day.

- The symptoms Powers experienced—abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting—are commonly associated with food poisoning, and in some cases can be severe enough to require hospitalization.

- Physicians attending to Powers in the hospital at first assessed his illness as acute gastritis, which is often attributable to food poisoning.49

The press corps reported the least disconcerting, physician-endorsed interpretation of evidence on hand: Powers had eaten bad food, experienced acute gastritis, and was taken to the hospital to treat the problem. They were wrong, but reporters could not have been expected to imagine that Powers was fatally ill with a rare disorder none of them likely had ever heard of.

The “sandwich” theory lacks empirical corroboration from primary sources, was not cited in physicians’ statements on etiology, and was quickly discounted once the true nature of the ailment became known. Yet the theory has persisted so long as to now enjoy a veneer of legitimacy, despite the surgeons announcing the very next day that Powers was suffering from intussusception, not acute gastritis.

The second hypothesis—the “injury” theory—comes in two variations: Either he injured himself when he dove for a foul ball or he crashed into a wall while chasing a foul ball.50

The origin of these explanations is difficult to pinpoint. Philadelphia-area newspapers did not include in their reporting on the April 12 game any on-field injury for Powers. Even if he had crashed into a wall or made an arduous dive for a foul ball, neither act was so extraordinary as to warrant mention in game coverage. Despite this, the idea that Powers “was perhaps the first major league baseball death traceable directly to an on-field injury” appears on numerous websites.51 They mistakenly assume that the need for three intestinal surgeries was caused by on-field injuries and then post-surgery infections (i.e., peritonitis) ultimately led to his death.52

Yet none of the medical reports issued on his condition—either before or after the first operation— identifies internal injuries. No such injury is cited in statements by the hospital or attending physicians as a causative factor. As in the case of the “sandwich” theory, the spurious basis for this explanation gives pause to wonder how it has remained even superficially legitimatized.

The “sandwich” and “on-field injury” explanations lack empirical merit and should be dismissed as baseless. Their falsity is made clear when they are evaluated within the context of what is known medically about the cause and course of intussusception, and official, documented statements made by doctors and the hospital on the illness and death of Michael Powers.

What is critical in understanding how Powers died is that the symptoms of intussusception probably appeared intermittently with varying intensity for several weeks or months before April 12.53,54 The physical examination and surgery make that indisputably clear. The mass doctors detected in the lower right portion of his abdomen was palpable, and its size enabled them to locate quickly the source of the excruciating pain he was experiencing.55 When they did operate, surgeons discovered that Powers had 15 inches of gangrenous intestine.56 That the gangrene had spread to that great an extent further demonstrates that intussusception had been present and progressed over a period of time. The mass and gangrene did not just form and expand on April 12.

Even if Powers ate a spoiled sandwich or injured himself going after a foul ball on Opening Day, neither act caused intussusception to occur, nor did either affect the disorder’s current state, rapidity of development, or onset of severe symptoms.57 As the attending physician’s statement affirms, agonizing pain associated with intussusception can begin “while peacefully lying in bed as readily as while strenuously exercising.”58 The food Powers ate and the physical activities in which he engaged on April 12 were irrelevant to the ailment’s advanced state and the deadly menace it posed.

The intussusception from which Powers was suffering was a severe, preexisting, and undetected disorder. The fact that pain associated with his disorder became intolerable on April 12 was a coincidence, and its timing was not dependent on what happened to Powers that day. The claim—or even suggestion—that Powers was the first major leaguer to die from an on-field injury is erroneous, not supported by the facts.

The Great Unsolved Mystery

There is one mystery associated with “Doc” Powers that will never be solved. No record exists that Powers alerted anyone about abdominal pain or any other discomfort prior to April 12. Medical knowledge of the disorder’s development leaves little doubt that he must have encountered some symptoms well before Opening Day.59 With his training and experience as a physician, it is highly improbable that Powers would not have noticed a “mass” had begun forming in his abdomen. Doctors noted it readily, which prompted them to operate at site.60

Given the great likelihood that Powers would have experienced pain and noted the mass, why did he not consult a physician when remedial action could have been taken? That Powers, himself a medical man, did not act sooner to preserve his own life is a great tragedy.61 Perhaps, like many people, he hoped the problem would go away on its own.62 Whatever signs Powers received that something was wrong, he chose to ignore them until it was too late to treat the ailment successfully.63

Grief and a Funeral

The death of “Doc” Powers was a great blow to the Philadelphia Athletics, major league baseball, and the City of Philadelphia. A distraught Connie Mack was quoted as saying:

Powers was the most popular man of the Athletics, and his loss is felt keenly by his teammates individually and collectively. To me his death comes as a great personal shock. He was the only player left of the team which opened the first American League championship season at Columbia Park, and there existed between us a bond of friendship that makes the separation doubly hard to bear.64

Flags at Shibe Park and down Lehigh Avenue at the Phillies’ National League Park were immediately lowered to half-mast. The Athletics announced that team players would wear knots of black ribbon on their jerseys for 30 days, and that the flags at Shibe Park would stay at half-staff for the same period.65

The Athletics’ Board of Directors met on April 27 and adopted a resolution that read in part:

That in the passing away of Mr. Powers this club has lost a valued companion, counselor and friend. His public career was a worthy exemplar of whatsoever is most praiseworthy in the national game which his efforts adorned and dignified. He was manly, loyal, discreet, courteous and capable. He inspired confidence on the playing field, warm friendships among his associates and profound affection in his own cherished home circle.66

Messages poured into the Athletics’ offices from other major league baseball clubs expressing grief, offering condolences to his family, and asking that floral arrangements be purchased on their behalf for the funeral. Every AL club—and Philadelphia and Brooklyn of the NL—sent a wreath.67

The body was moved from Northwest General Hospital to the home of close friend George E. Flood so that family, friends, and fans could pay their respects.68 Newspapers reported that Flood’s parlor, where the body lay in repose, was filled with flowers. One particularly striking, albeit macabre, arrangement was provided by the Sporting Writers’ Association of Philadelphia. According to one eyewitness, “It was a diamond of carnations laid out on a field of green ferns. Directly across the diamond were immense letters in white roses spelling ‘OUT.’”69

The funeral took place at St. Elizabeth’s Roman Catholic Church on April 29.70 The Athletics’ game scheduled that day against Washington was postponed so players from both clubs and team officials could attend the service.71 In addition, players from the Phillies and visiting Dodgers also were in attendance. The church was packed to capacity, and according to newspaper accounts, seven thousand people overflowed onto surrounding streets because they were unable to gain admittance.72

The celebrant of mass was Reverend Francis L. Carr of St. Patrick’s Church in Norristown, Pennsylvania, who was a personal friend of Powers. Carr told the congregation:

Dr. Powers lived and died a good man, and my prayers and those of every priest in this diocese, I am sure, are that Our Lord and Our Savior, Jesus Christ come to the aid of the wife and helpless children. Eternal rest to his soul.73

The pall bearers were Jack Coombs, Harry Davis, Danny Murphy, Simon Nicholls, Eddie Plank, and Ira Thomas. Powers was laid to rest at the New Cathedral Cemetery.74 The body remained there for only a month. It was moved and reinterred at the St. Louis Cemetery in Louisville, Kentucky.75

Philadelphia’s Evening Times newspaper started a subscription movement to obtain $1,000 in sums not to exceed $25 from any single donor in memory of Powers. The money was to be used to endow a bed at Northwest General Hospital for use by any professional ballplayer who was injured during a game or whose illness was directly attributable to playing in games during the regular season. The needed sum was soon raised.76

“Doc” Powers Day

Major league baseball players did not have pensions when Powers died.77 Although he was a physician, playing baseball had interfered with his ability to develop a thriving practice.78 Aware of this, Connie Mack approached AL president Ban Johnson about sponsoring a benefit at Shibe Park to financially aid the Powers family, including establishing an education fund for his three children.79 Johnson agreed, and June 30, 1910, was selected for the event because the four “eastern” AL teams—Philadelphia, Washington, Boston and New York—were off that day and could participate in the benefit game.80

To encourage attendance at what was officially called “‘Doc’ Powers Day,” the Athletics mailed thousands of postcards advertising the event.81 Tickets could be purchased at Shibe Park, Gimbels department store, and Spalding’s sporting goods store. The admission prices were a dollar for a reserved seat in the pavilion, 50 cents unreserved, and 25 cents for a bleacher seat.82

Two primary activities were scheduled: a series of baseball skills competitions and an exhibition game. The competitions were as follows:

- Running – Going to first base on a bunt; circling the bases; 100-yard dash for players weighing under 200 pounds; 100-yard dash for players weighing over 200 pounds (called the “heavyweight” class), four-man relay base running (i.e., one player running from home to first; the second player from first to second; the third player from second to third, the fourth player from third to home), each relay team representing an individual AL club.

- Throwing – For accuracy, distance, and novelty.

- Batting – Fungo hitting.83

The first and second place finishers in each of the above events, except relay base running, received a silver trophy cup. The four men comprising the winning team in relay base running would each be presented a cup.84 The trophies were provided by the Athletics.85

The winner in going to first base on a bunt in the shortest time was Harry Lord of Boston.86 He did so in 31⁄5 seconds. Five players—Eddie Collins, Frank Baker and Morrie Rath of Philadelphia, Tris Speaker of Boston, and Hal Chase of New York—tied for second place, covering the distance in 32⁄5 seconds. A drawing was held to determine who would win the second place cup, and Chase’s name was chosen.

First place in circling the bases most quickly was captured by Collins, who accomplished the feat in 141⁄5 seconds. There again was a tie for second place, with Jimmy Austin of New York and Tris Speaker traveling the distance in 143⁄5 seconds. After a toss of a coin, Austin was awarded the trophy cup.

Austin also won a first-place trophy, winning the 100-yard dash for players weighing below 200 pounds. He crossed the finish line in 103⁄5 seconds, with Harry Hooper of Boston capturing second place.

For the “heavyweight” class, Jake Stahl of Boston took home the top prize, completing the 100-yard dash in 104⁄5 seconds.87 Hippo Vaughn of New York came in second.

In the relay base running competition, Philadelphia and Boston tied at 143⁄5 seconds. The race was run a second time, and both teams matched again at 142⁄5 seconds. A coin toss was used to identify the winner, and the hometown crew took home the trophy cups.

In the throwing for distance contest, Hooper was the class of the field. His ball went 356 feet, four inches. Runner-up Speaker could only manage 345 feet, seven and a half inches.

In throwing for accuracy, the day belonged to Pat Donohue of Philadelphia. Germany Schaefer of Washington came in second.

The novelty throw was an evidently tough competition. Contestants were required to squat in the catcher’s position behind home plate and throw a ball over second base beneath a bar six feet high located at the pitcher’s mound. Only Austin was able to accomplish the feat, winning another first-place trophy.

Finally, Jimmy Dygert of Philadelphia captured first place in the fungo hitting competition, with second place belonging to Tom Hughes of New York.

The exhibition game between the Athletics and the “All-American” team composed of players from the other AL clubs was played with less than serious intent. Called a “horse play game” by one reporter, both teams made sweeping changes in their lineups each inning. The crowd enjoyed the spectacle, nevertheless, with one account noting that “the ragged playing of the league stars was greeted with delight.”88 Limited to six innings, the Athletics prevailed in the game, 5–3.89

The day’s festivities went beyond baseball. Clowns made appearances on the field at Shibe Park and performed a series of humorous skits as part of the entertainment. Schaefer and Boston’s batboy contributed to the fun by doing a pantomime act that satirized the antics of a big league pitcher-catcher battery.90

In addition, there was music courtesy of the Phillies. Club president Horace Fogel arranged to have the Banda Bianca Orchestra under the baton of Sig. Alfredo Tomassino play a number of selections including the overture from Light Cavalry and the sextet from Lucia. Also performed was The Phillies, a march written by Tomassino and dedicated to Fogel.91

The Sporting Writers’ Association of Philadelphia supplied the judges for the skills contests, and supported the fundraising campaign by having a special program printed for “Doc” Powers Day and selling it for ten cents apiece. All of the proceeds from the sale went to the Powers family.92 To encourage attendees to buy the program, each copy was numbered, and Florence Powers, who attended the event along with her children, chose two of the numbers in a drawing. One winner received a free pass to attend Athletics home games for the remainder of the season, while the other received a similar pass to attend the rest of the Phillies’ home games in 1910.93

“Doc” Powers Day was called “a grand success” in newspaper accounts. More than 12,000 people paid admission, including Connie Mack, to help swell the fund benefiting the Powers family. Approximately $8,000 was raised.94 Florence took the opportunity “to thank my friends and the followers of the Athletic team for their kindness on this day. I shall never forget it.”95

Athletics players appreciated manager Mack’s labors, compassion, and generosity in assisting their fallen teammate’s family. Before the exhibition game was played, they presented Mack with a large bouquet of flowers at home plate. Eddie Plank made the presentation.96

The staging of “Doc” Powers Day was a shining moment. No obligation existed in professional baseball to assist a family financially after a player’s death, but extraordinary steps were taken by many caring people—Mack, Johnson, players, sportswriters and the public—to do just that. France C. Richter, writing in Sporting Life, captured the importance of the occasion when he praised the day as “successful financially and artistically beyond any similar function in the history of base ball—and thus goes to Philadelphia’s credit another unexcelled achievement in base ball.”97

ROBERT D. WARRINGTON, a native Philadelphian, focuses his research and writing on the Philadelphia Phillies, 1883-1915, and the Philadelphia Athletics, 1901-14.

Notes

1. Period newspaper articles and retrospective pieces occasionally identify “Maurice” Powers. It is unclear why because his name was undoubtedly “Michael.” The name that appears on his tombstone, which also lists his birth and death dates, is “Michael.” See www.findagrave.com and search on “Michael Riley ‘Doc’ Powers” to see a photo of the tombstone. In the world of baseball, nevertheless, Powers was regularly called “Doc.”

2. “‘Doc’ Powers’ Condition is Serious after Operation,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 15, 1909. This article erroneously refers to Powers as “Maurice.”

3. Charles Dryden, “Doctor ‘Mike’ Powers,” The Athletics Sketches (October 1905): 22.

4. Philadelphia Inquirer, April 15, 1909.

5. Unless otherwise noted, offensive statistics, teams played for, transactions, and other information about the major league career of Michael Powers—is taken from www.Baseball-Reference.com.

6. David Jordan, The Athletics of Philadelphia: Connie Mack’s White Elephants, 1901–1954 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1999), 10.

7. David Nemec, The Great Encyclopedia of 19th Century Major League Baseball (New York: Donald L. Fine Books, 1997), 655. Whether Powers was offered an opportunity to play for one of the remaining eight NL teams or chose instead to play for the AL remains unclear. He was, nevertheless, one of the many players who shifted to the AL in 1900 when the NL reduced its structure from 12 to eight teams.

8. Norman Macht, Connie Mack and the Early Years of Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 184–93.

9. Jordan, Athletics of Philadelphia, 14.

10. Frederick G. Lieb, Connie Mack: Grand Old Man of Baseball (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1945), 66.

11. Jordan, Athletics of Philadelphia, 20.

12. George Graham, “Catcher ‘Doc’ Powers,” Powers Day Program, June 30, 1910, 6. The program included several testimonials to Powers written by Philadelphia newspaper sportswriters.

13. George M. Young, “The Man Behind the Bat,” Powers Day Program, June 30, 1910, 15.

14. Mark Stang, Athletics Album: A Photo History of the Philadelphia Athletics (Wilmington: Orange Frazer Press, 2006), 17.

15. Macht, Connie Mack, 439.

16. Plank’s annoying pitching style that catchers, hitters, fans and players in the field had to endure was one of his defining characteristics. SABR member Jan Finkel writes, “Eddie Plank fidgeted. On every pitch, Plank went through a seemingly endless ritual: Get the sign from his catcher, fix his cap just so, readjust his shirt and sleeve, hitch up his pants, ask for a new ball, rub it up, stare at a base runner if there was one, look back at his catcher, ask for a new sign—and start the process all over again. As if that wasn’t enough, from the seventh inning on, he would begin to talk to himself and the ball out loud: “Nine to go, eight to go…” and so on until he had retired the last batter. Frustrated hitters would swing at anything just to have something to do. His fielders would grow antsy. Fans, not wanting to be late for supper, would stay away when he was pitching. Writers, fearful of missing deadlines, roasted him.” Jan Finkel, “Eddie Plank,” Baseball Biography Project, http://bioproj.sabr.org.

17. Stephen O. Grauley, “Work Hard, Old Boy, Work Hard,” Powers Day Program, June 30, 1910, 16–17. The phrase “Work Hard, Old Boy, Work Hard,” was a favorite of Powers. He would periodically yell it at Plank during ballgames. It became indelibly associated with Powers and is frequently cited in stories written about him.

18. Ironically, Powers would die exactly eight years later: April 26, 1909.

19. Lieb, Grand Old Man, 70–71.

20. Waddell was sold to the St. Louis Browns after the 1907 season, and Schrecongost was sold to the Chicago White Sox during the 1908 season. Connie Mack added catcher Jack Lapp to the team’s roster that same year. With the loss of Powers after Opening Day in 1909, Ira Thomas, Paddy Livingston, and Lapp handled behind-the-plate duties for the team the rest of the season. None of these players contributed much offensively to the Athletics, but Mack accepted that in wanting them to catch for the club. As Norman Macht points out in his biography of the A’s manager, “Mack preferred a good brain over a good bat behind the plate any day.” Mack’s philosophy almost certainly harkened back to his playing days as a light hitting but savvy catcher. Macht, Connie Mack, 440.

21. Ibid., 343.

22. Shibe Park’s inaugural Opening Day has been written about extensively, and a detailed description of the event is beyond the scope of this article. For readers interested in learning more about the occasion, see, Rich Westcott, Philadelphia’s Old Ballparks (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996), 108–11.

23. Powers was transported to Northwest General Hospital because a physician from the hospital was at Shibe Park and, after making a “hasty diagnosis” in the clubhouse following the game, advised sending him there. The hospital is also referred to as Northwestern General Hospital in newspaper reports, and it is one of several hospitals in the city to which Powers could have been taken, “‘Doc’ Powers Near Doors of Death,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 26, 1909.

24. “Fully 35,000 Fans See Athletics Beat Boston in First Game of Season,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 13, 1909.

25. “Plank Was Too Strong for Boston and Athletics Win First Championship Game in Easy Style,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 13, 1909. In addition to Philadelphia-area newspapers reporting optimistically on prospects for recovery immediately after Powers had taken ill, Sporting Life contained a similarly positive assessment, observing, “As Sporting Life went to press Powers was reported as doing well with much improved chance for recovery.” “Maurice R. Powers,” Sporting Life, April 24, 1909. Note how this article incorrectly identifies Powers’ first name as “Maurice.” The early misdiagnosis probably contributed to the proliferation and longevity of erroneous assessments of the reasons for his illness and prospects for a quick and full recovery.

26. Chronologically details for April 12 are difficult to achieve precisely. The Opening Day game began at 3pm Assuming that it took approximately two hours to complete and that Powers was taken to the hospital soon after he collapsed in the locker room at game’s end, the best guess is that he arrived at Northwest General Hospital around 6pm His condition deteriorated later that evening, and doctors examining him discovered the mass in his lower right abdomen that prompted their decision to operate. The surgery took place at 1am on April 13. This sequence of events suggests doctors only conducted a thorough examination of Powers and found the mass late Monday night, several hours after his 6pm arrival at the hospital. In all likelihood, they initially assumed without examining Powers thoroughly that the symptoms he was exhibiting indicated the problem was acute gastritis, as newspaper stories on his condition reported. Many others supposed this as well, and it would explain why early reports from the hospital indicated Powers would recover and be back on the A’s roster in a few days. His worsening situation—almost certainly evidenced by escalating pain—aroused doctors’ suspicions that a more serious ailment was present and resulted in a more complete examination and determination that immediate surgery was required.

27. Philadelphia Inquirer, April 15, 1909.

28. “intussusception,” www.mayoclinic.com/health/intussusception/ DS00798. This article, prepared by Mayo Clinic staff, explains that when one part of the intestine—usually the small intestine—slides into an adjacent part, it is sometimes called telescoping because it is similar to the way a collapsible telescope folds together. The article provides an extensive description of the disorder and its treatment.

29. Ibid. Because of its rarity in adults, even today, symptoms of intussusception are challenging to identify and its causes difficult to pinpoint. It is usually the result of an underlying medical condition, such as a tumor, hematoma, or inflammation linked to Crohn’s disease or similar malady. The symptoms of intussusception include intense abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. While it can be deadly, intussusception can be treated successfully today without lasting problems.

30. Philadelphia Inquirer, April 15, 1909.

31. Frances C. Richter, “Death of Catcher Powers of the Athletics,” Sporting Life, May 1, 1909.

32. “Dr. Powers to be Buried Thursday,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 28, 1909.

33. Heart dilatation is an enlargement of the heart’s cavities beyond normal dimensions which causes thinning of the cavities’ walls. http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/dilatation+of+the+heart. Newspaper reports do not specify what symptoms Powers exhibited on the morning of April 25 that led doctors to conclude his condition had worsened. Symptoms commonly associated with acute heart dilation include fatigue, swelling of the lower extremities, abnormal heart rhythms, dizziness and chest pain. www.webmd.com/heart-disease/guide/dilated-cardiomyopal.

34. Connie Mack was described as being “all broken up over Powers’ condition.” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 15, 1909.

35. Philadelphia Inquirer, April 28, 1909.

36. Philadelphia Inquirer, April 26, 1909.

37. “Athletics’ Famous Catcher Died Yesterday Morning,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 27, 1909.

38. Philadelphia Inquirer, April 28, 1909.

39. The disorder was spelled differently in 1909 (“Interssusseption”) than it is today (“Intussusception”). The original spelling as it appeared in the surgeon’s report is used in the quotation as extracted from the Philadelphia Inquirer.

40. Philadelphia Inquirer, April 28, 1909.

41. Newspaper accounts track the diminution in prospects for recovery. At first, his chances were characterized as good because it was thought he was suffering only from acute gastritis. The initial report issued by Northwest General Hospital after the first operation was that he had “even chances of recovery.” A follow-up report from the hospital issued a week later changed what had been stated previously. The later assessment contended that doctors’ prognosis for his recovery after the first surgery was that he “had only one chance in five to live under any circumstances.” This far more dour assessment may have reflected an attempt by the hospital and its doctors to distance themselves from their earlier, more optimistic estimates of his prospects for recovery. After the second and third operations, the hospital stated that his case was virtually hopeless. Philadelphia Inquirer, April 15, 26, 1909.

42. Philadelphia Inquirer, April 28, 1909.

43. Philadelphia Inquirer, April 13, 1909. It is easy to reject as tosh the sportswriter’s suggestion that Powers had become overwrought with excitement attendant to playing in the inaugural Opening Day at Shibe Park. By 1909, Powers was a veteran with 11 years of major league experience. His overall calm demeanor and steady influence on pitchers was widely known and respected. There is no evidence or other reporting to indicate the catcher experienced frenzied discomposure that somehow contributed to the illness he suffered during the game.

44. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doc_Powers. It has been alleged that Powers stated he became ill after eating a cheese sandwich before the game, but the claim lacks documentation and is not confirmed by primary sources. Indeed, while Wikipedia includes the purported statement in its biographical sketch of the A’s catcher, there is a notation that a citation is needed to support it empirically. Other websites, nonetheless, have replicated the statement without including the caveat that it is unsubstantiated. See, for example, http://dbpedia.org/page/Doc_Powers.

45. “Catcher Powers Critically Ill,” The New York Times, April 15, 1909.

46. Westcott, Old Ballparks, 110–11. The contention that the sandwich Powers ate did not digest properly was never clarified in terms of what exactly was meant by the phrase, why the food had not digested properly, or how the absence of appropriate digestion caused the ailment. Like all claims that link the malady to a problematic sandwich, this hypothesis lacks documented corroboration and is nothing more than an unsubstantiated narrative.

47. How many sandwiches Powers ate and when he ate them are not essential to the theory, but instead reflect variations in the information that was used to support it initially and in reiterations of the theory that appeared in subsequent years.

48. www.symptomfind.com. Search under “Food Poisoning.” The website contains an extensive description of the causes, symptoms, treatment and prevention of foodborne illness.

49. http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/acute+gastritus.

50. www.baseballhistoryblog.com. Search under Michael “Doc” Powers. This website includes both variations of the “on-field injury” claim. The entry on the death of Powers states, “The root of the problem was never pinpointed in contemporary accounts.” This is rubbish. The account written by one of the surgeons and printed in the Philadelphia Inquirer on April 28 explained in detail the disorder afflicting Powers and how it led to his death.

51. Baseball-Reference.com“>http://Baseball-Reference.com. The suggestion is found in the “Biographical Information” section of the “Doc” Powers entry on the website.

52. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doc_Powers.

53. G. Gayer, et al., “Adult intussusception—a CT diagnosis,” British Journal of Radiology (2002) 75, 185–90.

54. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intussusception.

55. The surgeon’s report does not make clear whether the mass was observed visually or felt physically. In either case, it was readily apparent upon examination, making evident that it had been forming for some time.

56. Philadelphia Inquirer, April 28, 1909.

57. If the intussusception occurred as a result of an underlying medical problem, as referenced in note 29, it was never identified in reports on his condition or death.

58. Philadelphia Inquirer, April 28, 1909.

59. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2675089. Search under “Intussusception in Adults.” The study conducted on adults with intussusception indicates that the disorder develops and worsens over time, with abdominal pain the most common symptom followed by nausea and vomiting. Other symptoms exist as well. Research shows clearly that intussusception progressively reveals itself in more pronounced ways until suddenly and without warning pain and other symptoms become so severe that people must be rushed immediately to the hospital for surgery.

60. Philadelphia Inquirer, April 28, 1909.

61. Powers and the rest of the Athletics arrived in Philadelphia on April 2, 1909, after conducting spring training in New Orleans, stopping for exhibition games in Mobile and Atlanta, and heading home. The A’s then played a seven-game “City Series” against the Phillies. This timeframe gave Powers over a week in Philadelphia before the opener against Boston to consult physicians about his condition. There is no evidence that he did. Had he done so, it is almost certain that he would have been in a hospital bed being treated for his ailment on April 12 instead of on the playing field at Shibe Park. Information about the Athletics spring training in 1909 comes from, Barry Sparks, Frank “Home Run” Baker: Hall of Famer and World Series Hero (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2006), 23–26.

62. Judgments about the development of intussusception and its symptoms prior to April 12 must of necessity be estimative because all participants with firsthand knowledge of his condition are long dead, and none of the newspaper or other reports on the ailment after he had taken ill at Shibe Park address whether he experienced beforehand indications of a medical problem. Nonetheless, based on what is known of intussusception and Powers after his excruciating pain began at Shibe Park, it is highly likely symptoms of the disorder appeared prior to April 12.

63. It is impossible to determine with certainty whether earlier detection and treatment would have enabled Powers to live a longer life. The statement issued by one of the surgeons who treated Powers noted that the mortality rate for intussusception “is usually very high.” While the statement was undoubtedly intended in part to preclude questions over whether the quality of care Powers received at Northwest General Hospital was in any way responsible for his death, no one questioned the surgeon’s assertion that it is a “generally fatal condition.” Nevertheless, hospital bulletins on his deteriorating condition emphasized the ailment’s advanced stage of development when treatment began. While intussusception was more deadly in 1909 than it is today, if treatment had started at a much earlier stage of the ailment’s development—for example, before gangrene had occurred and spread—then chances for recovery would have improved.

64. Philadelphia Inquirer, April 27, 1909. By the start of the 1909 season, just “Doc” Powers, Eddie Plank and Harry Davis remained on the A’s roster from the original 1901 team. Powers was the only one of the three, however, who appeared in the first game ever played by the Athletics on April 26, 1901.

65. Philadelphia Inquirer, April 28, 1909.

66. “Athletic Directors Pay Tribute to the Memory of Doctor Powers,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 28, 1909.

67. Philadelphia Inquirer, April 28, 1909.

68. Ibid. Flood’s home was located at 2035 North Twenty-Second Street.

69. “Unusual Tribute Paid to Memory of Dr. Powers,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 30, 1909.

70. Ibid.

71. Macht, Connie Mack, 439.

72. Philadelphia Inquirer, April 30, 1909. The last time the City of Philadelphia had witnessed such an outpouring of grief over the untimely death of a baseball player was 21 years earlier when Charles Ferguson, a star for the Phillies who was on his way to fashioning a Hall of Fame career, died from typhoid fever. He was only 25 when he passed in 1888. See, Frank Fitzpatrick, “Charlie Ferguson Seemed Headed for a Place in Baseball Lore: The Short Life and Tragic Death of a Long-Ago Phillies Phenom,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 23, 2003.

73. Philadelphia Inquirer, April 30, 1909.

74. Ibid.

75. Frances C. Richter, “In Memory of Powers,” Sporting Life, June 5, 1909. Florence Powers relocated with her children back to her hometown of Louisville, Kentucky, soon after his death. She died 60 years after her husband on August 18, 1969, and was laid to rest beside him. www.findagrave.com.

76. Ibid.

77. G. Edward White, Creating The National Pastime: Baseball Transforms Itself, 1903–1953 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996), 121–22. The All-Star Game was inaugurated and first played in 1933 in part to generate funds to give financial aid to destitute former players. According to White, “The pension created by All-Star Game receipts marked the first systematic effort on the part of Organized Baseball to pay attention to the welfare of players from its past.”

78. Philadelphia Inquirer, April 15, 1909.

79. George E. McLinn, “Thoughts For His Family,” Powers Day Program, June 30, 1910, 13.

80. “Local Fans Do Not Forget The Late Dr. Powers,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 1, 1910.

81. Macht, Connie Mack, 439.

82. “Shibe Park—Powers Day Today,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 30, 1910.

83. Powers Day Program, June 30, 1910, 4.

84. Ibid.

85. Frances C. Richter, “Dr. Powers Day,” Sporting Life, July 9, 1910.

86. The results for all competitions are taken from, “Powers Day Games Held at Shibe Park,” The New York Times, July 1, 1910.

87. There is a discrepancy in reporting on Stahl’s time. It is variously recorded as 102⁄5 seconds and 104⁄5 seconds. The former figure is shown in Richter, Sporting Life, July 9, 1910. The latter is contained in The New York Times, July 1, 1910.

88. Philadelphia Inquirer, July 1, 1910.

89. “Powers Day” is a Grand Success,” Washington Post, July 1, 1910.

90. Philadelphia Inquirer, July 1, 1910.

91. Powers Day Program, June 30, 1910, 8.

92. Ibid.

93. Richter, Sporting Life, July 9, 1910. The holder of program number 2119 won the Athletics’ pass, and the holder of program number 1616 took home the Phillies’ pass.

94. Washington Post, July 1, 1910. That Connie Mack also paid admission is noted in Macht, Connie Mack, 439. The total revenue raised is variously reported as $8,000 and $7,000, with the former figure cited most often as the amount. Macht reports the higher amount, while Sporting Life cites the lower figure. Richter, Sporting Life, July 9, 1910.

95. Richter, Sporting Life, July 9, 1910.

96. Ibid.

97. Ibid.