A Bitter Rivalry Recalled: The Cleveland Indians and the New York Yankees, 1947–1956

This article was written by James E. Odenkirk

This article was published in The National Pastime (Volume 28, 2008)

The late Ed Linn, coauthor of Veeck—As in Wreck, later wrote in The Great Rivalry (1991), “I don’t care what anybody says, there is no rivalry on the face of the earth that can compare with the Yankees and Red Sox.”1

Linn, who died in 2000, might have been able to justify that statement more easily had he qualified it to cover only the period since 1990 or so. The intensity of the Yankees–Red Sox rivalry since then is indisputable. It is enthusiastically hyped in the media, print and broad- cast alike, particularly ESPN. In the mid to late 1990s, Red Sox Nation was reinvigorated by teams that, at least at times during the regular season and finally in the American League Championship Series in 1999, were competitive and that battled the re-emergent Yankees dynasty toe-to-toe. At times, regular-season games took on the aura of playoffs.

The “Curse of the Bambino,” still assumed to be operative, was finally swept away when the Red Sox won the World Series in 2004; Dan Shaughnessy, noted sportswriter for the Boston Globe, popularized the notion with his book The Curse of the Bambino, published in 1990. The theme of the curse took on a life of its own and entered baseball language. Glenn Stout referred to the Curse as “a nice hook, but not very good history.”2 Peter Gammons described the phrase as a “silly, mindless gimmick that is as stupid as the wave.”3 Spurned by knowledgeable fans, it largely faded away after the two Red Sox championships in recent years.

Observers have long questioned the description of the Red Sox as the Yankees’ rival, “one that equals,” according to Merriam-Webster’s, “another in desired abilities.” From 1918 (when Boston edged out Cleveland for the pennant) through 2003, the Yankees had won twenty- six World Series. The Red Sox had won—one. The ratio hardly represented equality. Since 2004, pundits have been less inclined to dismiss competition between the Yankees and the Red Sox as an entirely predictable con- test between “the hammer and the nail.”4

Boston or Cleveland? Cleveland

This author humbly thrusts himself into the fray. I have been a close observer of Major League Baseball since the mid-1930s. During the remarkable period 1947–56, as I see it, the dominant rivalry in the American League was Yankees–Indians, not Yankees–Red Sox. My argument is supported by two sets of statistics. The first is the performance of the Yankees, Indians, and Red Sox on the field. The second is attendance figures for games between the Yankees and Red Sox and for games between the Yankees and Indians.

The Yankees won four straight world championships in the late 1930s, only to have my beloved Indians, briefly known as the “Crybabies” in 1940, lose to Detroit that year in a pennant race in which Cleveland for once had the inside track. The Yankees won pennants again in 1941, 1942, and 1943 and the World Series in 1941 and 1943, but the worst was yet to come.

During the twelve-year span from 1947 through 1958, the Bronx Bombers won ten pennants and eight world championships. The only other team to win the American League pennant during that period was the Cleveland Indians. Since the Yankees’ first World Series appearance, in 1921, the only teams to beat them there were the New York Giants (1921, 1922), the St. Louis Cardinals (1926, 1942), the Brooklyn Dodgers (1955), and the Milwaukee Braves (1957). And hence the expression “damn Yankees,” which may have had its origins as a derogatory term for Union soldiers during the Civil War but by the second half of the twentieth century had come to be firmly associated with the New York team of the American League.

In contrast, only three times between 1920 and 1948 did the Cleveland Indians finish the season within 101⁄2 games of the pennant winner, eliciting variations on the theme of “wait until next year,” a saying made famous in Brooklyn. For a period of ten years, however, it was the Indians, not the Dodgers or the Red Sox, who posed the most persistent challenge to the Yankee dynasty.

At the outset of the Great Depression, Boston and Cleveland were comparable in size. According to the U.S. census of 1930, the populations of Boston and of Cleveland were 781,000 and 900,000, respectively.5 During and after World War II, the migration of African Americans from the South to the industrialized North was significant, but, even so, the populations of the two cities remained about the same, 801,000 and 915,000, although in both cases the metropolitan area, consisting of outlying suburbs, grew substantially.6 Television was in its infancy in the late 1940s, beset with numerous technical difficulties and an overabundance of snow on the screen. For detailed information about their favorite teams, fans relied on Baseball Magazine, The Sporting News, and metropolitan newspapers. Three Cleveland newspapers were highly competitive in their effort to provide readers with deep reporting about the fortunes of the Tribe. The local sportswriters were excellent. Two of them, Gordon Cobbledick and Hal Lebovitz, would be inducted into the writers wing of the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Boston fans read about the Boston Millionaires (a name often identified with their local team after millionaire Tom Yawkey purchased the franchise in 1933)7 in one of four dailies, particularly the Boston Globe, which featured sportswriters Dave Egan and Al Hirshberg. Fans in all three cities eagerly listened to radio broadcasts of the games described by Curt Gowdy (Boston), Mel Allen (New York), and Jimmy Dudley (Cleveland), all of whom would receive the Hall of Fame’s prestigious Ford C. Frick Award.

“Best Location in the Nation”

How and why did the Indians rise to become the major challenger to the Yankee dynasty during the decade after World War II? The answer begins with a brief look at the history of Cleveland’s rapid growth in the period leading up to that point. The Forest City had been a major industrial center since the turn of the twentieth century. Cleveland was very much “alive” after the war ended in August 1945. Despite inflation, fans had disposable in- come and were eager to support the home team. By 1948 local journalists and advertisers had dubbed Cleveland, the sixth largest city in the country, “City of Champions” and, what proved to be a more enduring title, “Best Location in the Nation” (both of them a far cry from the moniker “Mistake by the Lake,” which in later decades would attach to Municipal Stadium, home of the Indians and the Cleveland Browns).8 The Cleveland Buckeyes had won the National Negro Baseball Championship in 1945. The Cleveland Barons consistently challenged for or won the Calder Cup in the American Hockey League, and the Browns in their early years dominated the All-American Football Conference and then, later, the National Football League.

But what about the Tribe, the professional team with the longest history in Cleveland? It had been 26 years since their last and only world championship when, in 1946, a 32-year old ex-marine named Bill Veeck bought the Indians and established the foundation for rapid success, which included some classic battles between Cleveland and New York. Veeck set three main goals: a pennant, increased fan interest, and increased attendance.

Before 1947, the Tribe played most of their home games in cozy and quaint League Park, whose seating capacity, though it shifted as the facility was renovated over the years, never exceeded 27,000. I watched my first major-league game there in 1936 and saw Hal Trosky stroke a home run over the close right-field wall (290 feet from home plate at the foul line), which, however, was 40 feet high, the top 20 feet consisting of chicken wire held up with steel beams. Except for the second half of the 1932 season and all of 1933, the Indians used Municipal Stadium, a cavernous facility on the shore of Lake Erie, only for weekend games and select night games—until 1947, when they abandoned League Park and scheduled all their games for the Stadium, which sat 78,000. Veeck toured Ohio during the winter to promote the rejuvenated Cleveland Indians to any school, church, service club, business, or bar that would listen to him.9 He scheduled all kinds of gameday promotions, some zany, some sentimental, but all with the idea of making a day at the ballpark fun.

Veeck’s efforts soon paid off. The Indians won the World Series in 1948. Attendance was 2,620,627, which still stands as the record for the 77-game home schedule of the pre-expansion era.10 Veeck sold the club after the 1949 season, and in 1950 the Indians came under the leadership of Hank Greenberg, the Hall of Famer, who was now appointed vice president and general manager. Through 1956 the Tribe would remain a consistent contender.

Meanwhile, Veeck, following the lead of Branch Rickey over in the National League, signed to a major- league contract 23-year old Larry Doby, the first black player in the American League.11 The following summer he signed the venerable Leroy “Satchel” Paige. A baseball icon, Paige drew thousands to the ballpark, both home and away. The lanky pitcher went 6–1 to help the Indians on their way to narrowly winning the pennant and then their first world championship in 28 years. In addition to future Hall of Famers Doby and Paige, eleven other former Negro Leaguers, including first baseman Luke Easter, debuted with the Tribe between 1949 and 1956.

The wary Veeck was unsure how Cleveland’s fans would react to an integrated team. He knew that in professional football the Cleveland Browns had set precedent by signing Marion Motley and Bill Willis in 1946. Veeck appreciated that Cleveland’s growing African American community was a source on which he could draw to increase the team’s fan base. In 1950, one seventh of the people living in Cleveland proper were black.

The Yankees did not integrate until much later, signing Elston Howard to a minor-league contract in 1950; he would not debut with the major-league team until 1955. In Boston, which had been a capital of the antislavery movement a century earlier, the Red Sox were slow to join the rest of Major League Baseball in razing the color barrier. Owner Tom Yawkey, manager Pinky Higgins, and general manager Eddie Collins were all perceived to be quietly resisting integration. When Elijah “Pumpsie” Green debuted with Boston in 1959, the Red Sox became the last major-league team to embrace what Jules Tygiel called “baseball’s great experiment.”12

Municipal Stadium, Yankee Stadium, Fenway Park

The main pillar on which my argument rests is attendance—attendance at games between the Yankees and Red Sox and at games between the Yankees and Indians. (I do not consider attendance at games between the Indians and Red Sox, as I assume that fans of neither team perceived the other team as the primary obstacle to their goal of winning the pennant.)

Two important variables influenced attendance. First, it can be assumed that it was depressed by inclement weather, particularly in the early weeks of the season. Second, the seating capacities of the three ballparks differed significantly. At Municipal Stadium in Cleveland, it shifted somewhat over time but never fell below 73,000 during the period in question. Yankee Stadium sat 67,000, and Fenway Park only 35,000. In both leagues, the regular season was 154 games, each team playing 22 times against each of seven league opponents.

Standing in stark contrast to old League Park, Municipal Stadium was built in part for the Indians but also for other large public events. Every year during the period 1947–56, the Indians’ attendance exceeded 1 million, a figure high for that era. The Stadium was demolished in 1996, and by the time you read this the old Yankee Stadium may have already given way to the nearby smaller replica that is still under construction as I write. In baseball, the football-size crowds that some of the old facilities could accommodate are becoming obsolete, as the trend toward major-league ballparks that are relatively small and intimate shows no sign of abatement.

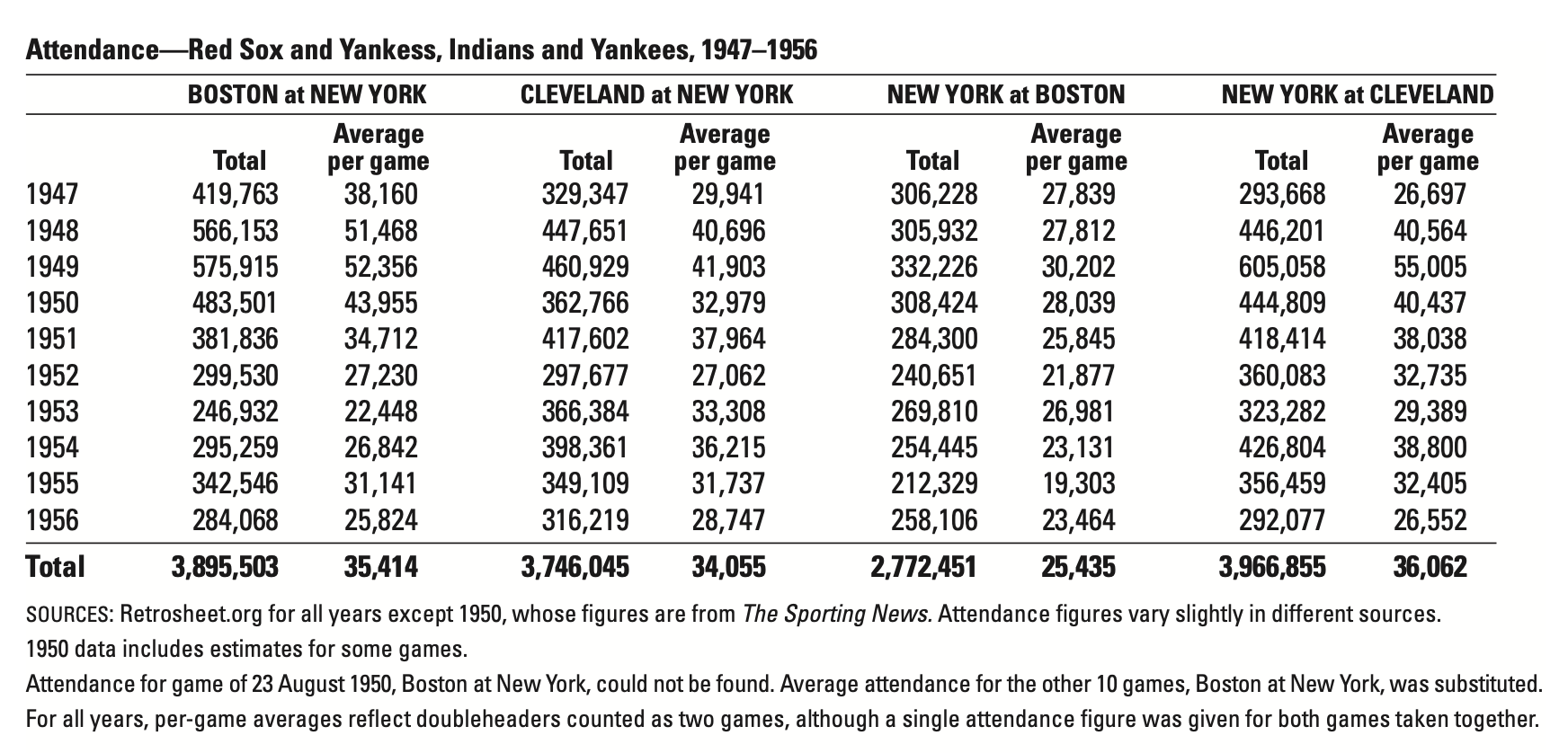

As would be expected, given the size of their venues, Cleveland and New York had higher attendance figures than did Boston. The Indians during this period drew 3,966,855 when playing the Yankees in Cleveland. The Yankees during the same period drew 3,746,045 when playing the Indians in New York; when playing the Red Sox in New York, they drew only slightly more, 3,895,503.13 See table below.

Attendance—Red Sox and Yankees, Indians and Yankees, 1947–1956

(Click image to enlarge)

Of the 109 home games that the Red Sox played against the Yankees in Boston, 30 of them drew fewer than 25,000.14 Yankees–Indians in Cleveland fell below 25,000 only 25 times. Average attendance at a game between the Yankees and Red Sox was 25,435 in Fenway Park, 35,414 at Yankee Stadium. Average attendance at a game between the Yankees and Indians was 36,062 in Cleveland, 34,055 in New York.

These attendance figures suggest that, in New York, the Yankees’ rivalry with the Indians was felt to be almost exactly as strong as the Yankees’ rivalry with the Red Sox. The difference was that Clevelanders were more drawn to the Indians’ rivalry with the Yankees than Bostonians were drawn to the Red Sox’ rivalry with the Yankees. The large difference between the seating capacities of Municipal Stadium and Fenway Park might appear to make that assertion problematic, but in fact Yankees–Red Sox in Boston drew more than 33,500 (a sellout was 35,000) only 21 times. Attendance fluctuated throughout the period and, predictably, declined in Boston in the 1950s as the Red Sox’ performance declined. Throughout the period taken as a whole, the Cleveland–New York matchup drew more fans in New York and Cleveland taken together than Boston–New York drew in New York and Boston taken together. While attendance for all matchups in the American League remain to be tabulated, it is at least reasonable to assume that none exceeded Cleveland–New York.

It was an event whenever the two chief contenders for the American League pennant met. From Public Square in the heart of downtown Cleveland, thousands would walk toward the long flight of stairs near the West Third Street railway bridge and then make their way down the walkways leading to the lakefront stadium. Yankees– Indians games during this period in Cleveland drew 24 crowds of more than 60,000. Of those, 11 were more than 70,000, and one even exceeded 80,000. Attendance at the Yankees–Indians doubleheader on September 12, 1954, was 86,563, a regular-season record that still stands.

New York, Cleveland, Boston—and usually in that order

What accounts for the intensity of this rivalry between the Indians and Yankees? All three teams—Boston, Cleveland, New York—were loaded with veteran players and tended to match up well against each other.

On December 6, 1946, Veeck completed a trade that would later prove to be decisive for his team’s fortunes, enabling the Indians, a couple of years later, finally to get past the New York Yankees. He sent them catcher Sherman Lollar and second baseman Ray Mack for pitchers Gene Bearden, Al Gettel, and outfielder Hal Peck; Bearden, critically wounded in South Pacific action, would have only one good season, 1948, but what a season—the Indians could not have won the pennant and World Series without him. A couple of months earlier, on October 11, 1946, the Yankees sent second baseman Joe Gordon to the Indians for pitcher Allie Reynolds—a trade that can be said to have benefited both teams. “The Gordon–Reynolds trade was one of those deals that won pennants for each side,” Veeck wrote. “You can’t ask for anything fairer than that.”15

During this ten-year period, the Bronx Bombers won eight pennants, the Tribe two, and the Red Sox were shut out, although they had won the pennant in 1946. Most disheartening for the Indians was that they regularly finished second to the Yankees, a theme that had come to define the managership of Al Lopez. Lopez met with general manager Hank Greenberg after the 1955 season with the idea of resigning, citing “stomach problems” brought on partly by the frustration of being the runner- up in the American League in four of the five past seasons. Greenberg talked Lopez into staying. Again, the Indians finished second, again to the hated Yankees. After the 1956 season, Lopez finally did resign, and Greenberg was fired after the 1957 season.16

The intense rivalry between Cleveland and New York began to unravel. Casey Stengel’s Yankees would not surrender their apparent lock on the American League pennant, and neither the Indians nor the Red Sox could break it. During 1947–56, New York’s record was 123–97 against the Indians, 124–95 against the Red Sox. The Indians won the season series with New York only once; they split twice.17 The Red Sox won once, split once. Another telling statistic is derived from the simple formula whereby each of the three teams is awarded points corresponding to the position where it finished in the standings. As in golf, the low score wins. The Yankees during this period finished with 13 points, the Indians with 23, and the Red Sox with 35.

Given the Tribe’s famously outstanding pitching during this era, why didn’t it fare better? The four-man rotation of Bob Feller, Bob Lemon, Early Wynn, and Mike Garcia is arguably the greatest in the history of the game. Among them, Indians pitchers had seventeen 20-win sea- sons during this period. The Yankees had six. The Red Sox and Yankees had several pitchers with victory numbers in the high teens, but Red Sox pitchers could claim only three 20-game seasons, one by Ellis Kinder and two by Mel Parnell.18 The Most Valuable Player award went to a Yankee six times during the ten-year period, whereas the Indians claimed two, the Red Sox one.19

Cleveland’s woes begin to mount

And so a golden era for the Tribe and the city of Cleveland was coming to a close. Losing seasons would become the rule, year after year. The Indians staged one more valiant effort, in 1959, only to fade in September, as so often happened, and lose out to the “Go-Go” White Sox, owned by none other than Bill Veeck and managed by none other than Al Lopez.

In his novel Crooked River Burning, Mark Winegardner, a native Clevelander, captured the disappointment and sense of despair that had come to grip his hometown and its baseball team. Considering Game 1 of the 1954 World Series, between the Indians and another New York team, the Giants, he writes:

Bad enough that this has to happen, why does it have to happen in New York. . . . Because, God is the most shameless of classical dramatists. The ostensibly inconsequential moment that will presage Cleveland’s descent into loserdom and laff-riot Rust Belt pathos must necessarily come at the hands of its nemesis. Apotheosized in the gloved hand of young, racing, dashing Willie Mays. It figures. If a thing is going to happen, it figures it’s going to happen to Cleveland. Cleveland gets past its nemesis, the Yankees, who won every damned pennant since Cleveland’s last one. And what happens? Right! New Yorkers may be surprised to learn that the rest of America has been scorned, abandoned, and upstaged by New York so often as to render “New York underdog” oxymoronic.20

As an aside, I will add that I could share the sentiment Winegarnder so eloquently expresses here—I had tickets for Game 5 of the 1954 World Series. I later enjoyed a bit of retribution in 1958 when, as a graduate student at Columbia, I attended my first World Series game and saw Warren Spahn and the Milwaukee Braves shut out the Yankees 3–0.

The decline of Cleveland’s baseball franchise coincided with that of the city itself. In 1969, the Cuyahoga (an American Indian name meaning “crooked river”) actually caught on fire, becoming a symbol of the state into which Cleveland had fallen. To the rest of America, it had come to epitomize Rust Belt blight. Industries in this once proud city were in disarray. After the election of Carl Stokes in 1967, it did enjoy the distinction of becoming the first major American city to elect a black mayor, but the race riots it suffered in the late 1960s quickly took their toll. On its way to becoming a one-newspaper town, the city saw the Cleveland News fold in 1960 and the Cleveland Press bleed circulation until it too closed its doors in 1982, leaving only the Plain Dealer standing. By 1970, Cleveland’s population had dropped markedly. A major exodus to the suburbs left parts of the inner city in sham- bles. It was not a pretty sight.

The Tribe begins its forty years in the desert

Four factors contributed heavily to the Tribe’s travails. The first involved the Yankees in a way that no one could have expected. On May 7, 1957, Herb Score, the best young pitcher in baseball, the American League Rookie of the Year in 1955 and AL strikeout leader in 1955 and 1956, was nearly blinded when he was hit in the right eye by a line drive off the bat of New York’s Gil McDougald at the Stadium in front of 18,386 horrified fans. He did not lose his eye, and Score claimed that it was a sore elbow that kept him from regaining his old form. Whatever the reason, he would never be a consistently effective pitcher again. After struggling with the Indians and then the White Sox, he retired after the 1962 season and a couple of years later began his second career as the Indians’ TV and then radio announcer.

Second, Frank “Trader” Lane, hired as general man- ager in 1958, traded away some of the best talent that the Indians didn’t lose to injury. His first year on the job he sent outfielder Roger Maris, pitcher Dick Tomanek, and infielder Preston Ward to the Kansas City “Yankees” for shortstop Woodie Held and first baseman Vic Power.21 To the surprise to no one, Maris would be in a New York Yankee uniform within two years, and the rest is history. Two years later he brought down on Cleveland the “Curse of Rocky Colavito” when he traded Colavito to the Detroit Tigers for outfielder Harvey Kuenn. Colavito, a slugger, was a fan favorite in Cleveland. In the mid-1950s he and Score were seen as the core of the next generation of the great Tribe powerhouse. Kuenn, a good defensive outfielder, had hit .353 in 1959 to win the American League batting title. A singles hitter, he hit .308 in 1960 and was then traded at the end of the season.

Third, soon after Veeck sold the team in 1949, Indians ownership entered a phase during which it changed hands frequently. From 1949 until the Jacobs brothers bought the team in 1986, it was controlled by as many as nine different owners. Most of them were ineffectual, and at times the club was near bankruptcy. I recall attending an Indians game in May in the early 1980s and being interviewed by a local TV station. The weather was terrible. About 6,000 fans were on hand, and the Indians were losing. The interviewer asked, “Why are you here?” I didn’t have a good answer. Rumors persisted that the club would be relocated to New Orleans, Denver, or some other city. The team had long ago taken on the character of a small-market franchise.

Finally, the rivalry between the Indians and the Yankees received a heavy blow from league expansion and the realignment of teams into divisions. With the redistribution of teams across three divisions in 1994, the season series between the two teams was reduced to 14 games (only 9 of which were played that year, because of the work stoppage). A further reduction, to as few as 6 or 7 games (it varies from year to year), followed the introduction of interleague play in 1997. Conversely, the season series between the Yankees and the Red Sox remains 18 (and, some seasons, 19) games, a condition that supports their ability to maintain their rivalry at a level that exceeds that of the great Yankees–Indians rivalry in the decade following the end of World War II.

A tale of three cities

The Indians went deep in the tank during the 1970s and ’80s, and the Yankees and Red Sox also had their down times during that period. Since 1995, however, all three teams have winning records and have enjoyed stretches during which they have been dominant. The Yankees have won four World Series and ten division titles. The Red Sox have put to rest the Curse of the Bambino with two titles and two World Series championships. The Indians have gone some considerable distance toward burying the Curse of Rocky Colavito, having won seven division titles and made two appearances in the World Series, and, in the process, defeated the Yankees in two of three playoff engagements.

Attendance for game of 23 August 1950, Boston at New York, could not be found. Average attendance for the other 10 games, Boston at New York, was substituted. For all years, per-game averages reflect doubleheaders counted as two games, although a single attendance figure was given for both games taken together.

The success of these three franchises during the past decade or so, under varying division alignments and play- off configurations, brings back memories from what is sometimes described as the golden era of baseball.22 One major difference between then and now is the size of some of the crowds back then. On the whole, attendance was lower, but to hear of the exceptional crowds of 70,000 or even 80,000 for high-stakes games is striking to fans in these early years of the twenty-first century, when the big stadium has been supplanted by the smaller ballpark. Still, for the most part it was baseball as we know it today. The enthusiasm, the disappointment in defeat, and the exultation of victory were much the same as they are now. The titanic struggle between the Red Sox and Yankees that has dominated the baseball universe in recent years had its forerunner in the great Yankees–Indians rivalry of the past. Much like the Red Sox today, the Tribe back then both lost and won in its mighty struggle to defeat the New York Yankees, the most successful professional sports team in America in the twentieth century, but the twenty-first century belongs to—time will tell.

JAMES E. ODENKIRK, professor emeritus from Arizona State University in Tempe, is the author of “Frank J. Lausche: Ohio’s Great Political Maverick” (Orange Frazer Press, 2005) and “Plain Dealing: A Biography of Gordon Cobbledick” (SpiderNaps, 1990). An earlier version of this article was delivered at the SABR annual convention in Cleveland in June 2008.

Notes

- Ed Linn, The Great Rivalry: The Yankees and the Red Sox, 1901–1990. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1991), ix.

- Glenn Stout and Richard Johnson, eds., Red Sox Century: 100 Years of Red Sox Baseball. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000).

- Dan Shaughnessy, Reversing the (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2005), 9.

- Ibid, 21

- Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930, vol. 3, parts 1–2 (Washington, C.: Department of Commerce, 1932), 519, 1110.

- Seventeenth Decennial Census of the United States, 1950, vols. 1–2 (Washington, C.: Department of Commerce, 1952), 1:35–91, 2:21–67.

- Steven Riess , ed., The American League, vol. 2 of Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball Clubs (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2006), 2:514.

- Steven Riess, ed.. Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball Clubs, 584–85.

- Riess, The Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball Clubs, 2:582.

- Ibid, 2:584.

- Terry Pluto, Our Tribe: A Loving Look at a Thirty-Year Slump (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1999), 144–50.

- Riess, Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball Clubs, 519–20.

- Attendance figures are drawn from .org except for the year 1955, which reflects data drawn from both Retorsheet and The Sporting News. The Sporting News, 1947–56; New York Times, 1947–56.

- The Red Sox played 11 games a year against the Yankees at Fenway Park except for 1953, when they played 10.

- Bill Veeck, with Ed Linn, Veeck—As in Wreck (New York: Putnam, 1962), 144

- Russell Schneider, The Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia, 71, 343.

- In 1954, when the Indians set an American League record by winning 111 games, their record against the Yankees was 11–11. The temptation to look for some numerological significance is hard to resist.

- Joseph L. Reichler, ed., The Baseball Encyclopedia. (New York: Macmillan, 1988), 396–413.

- Ibid, 35.

- Mark Winegardner, Crooked River Burning, 183

- Russell Schneider, The Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia, 72, 75.

- R.W. Apple, “Oh, to Be in Cleveland, Now That Pride Is There,” New York Times, 22 October 1995.