A Crank on the Court: The Passion of Justice William R. Day

This article was written by Ross E. Davies

This article was published in Fall 2009 Baseball Research Journal

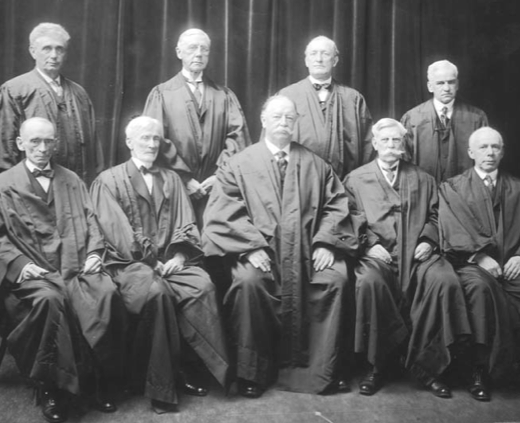

The U.S. Supreme Court, 1921–22. Back row, left to right: Louis D. Brandeis, Mahlon Pitney, James McReynolds, and John H. Clarke. Front row, left to right: William R. Day and Joseph McKenna, Chief Justice William Howard Taft, and Oliver Wendell Holmes and Willis Van Devanter. (Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States)

There is an understandable tendency to date the Supreme Court’s involvement with baseball from 1922, when the Court decided Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore v. National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs — the original baseball antitrust-exemption case.1 And there is a corresponding tendency to dwell on William Howard Taft — he was chief justice when Federal Baseball was decided2 — when discussing early baseball fandom on the Court.3

The first tendency is not only understandable but also pretty much correct. The Court heard only a few baseball-related cases before 1922, and none was especially weighty from either a legal or a baseball perspective (although each was surely important to the people involved).4

The second tendency, while also understandable, is not so correct. Taft was a baseball fan, but he was neither the first nor the most fanatical on the Court that decided Federal Baseball, not by a long shot.

Justice Joseph McKenna was first, which is easy to prove: He was a fan,5 and he was the longest-serving member of the Court at the time Federal Baseball was decided.6

Justice William R. Day was the most fanatical, which is not so easy to prove: The sketches of Taft-the-fan and Day-the-fan that make up the bulk of this article are intended to give readers enough information to decide for themselves. After considering those sketches and the sources on which they are based, reasonable minds might differ about whether Day was the most intense of the many intense followers of baseball who have served on the Court — good cases might be made for several others, including Chief Justice Fred Vinson7 and Justices Potter Stewart,8 Harry Blackmun,9 John Paul Stevens,10 Samuel Alito,11 and Sonia Sotomayor12 — but none would dispute that he at least deserves a place among them.

Not surprisingly, there were plenty of other baseball fans on the Court during, and even before, the period covered by McKenna’s (1898–1925), Day’s (1903–22), and Taft’s (1921–30) service.13 Chief Justice Edward D. White (1894–1921)14 and Justices John Marshall Harlan (1877–1911),15 Horace H. Lurton (1910–14),16 and Mahlon Pitney (1912–22),17 for example. And no doubt a thorough search would turn up many more.18 There is, however, nothing to suggest that up to 1922 any member of the Supreme Court was either as deeply interested in the game as Day was or portrayed as being as deeply interested in the game as Taft was. And so we turn to Taft and Day in their very different capacities as fans of the national pastime.

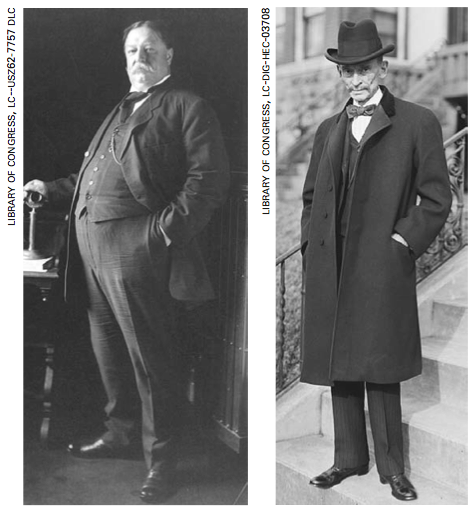

William Howard Taft, left, and William R. Day, right. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

William Howard Taft, left, and William R. Day, right. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

WILLIAM HOWARD TAFT, THE OFFICIAL-CAPACITY FAN

Attention to Taft over Day in the context of baseball is understandable both because Taft was, and remains, so much more noticeable than Day and because Taft was, in fact, a baseball fan of a sort, if not a particularly intense one.

Taft’s superior noticeability began at a personal level, with the physical differences between the two men. Taft was a very substantial human being, an attribute noted and caricatured in the news media (see, for example, the cover of Judge magazine on page 96)19 and even privately among his friends.20 Day, in contrast, was sufficiently slender and frail — “of delicate physique,” as his diplomatic colleague Justice Charles Evans Hughes put it21 — to be the target of the occasional cartoon (see, for example, “midget” Day on page 97) or friendly barb as well.22 At a professional level, there were substantial differences too. Both men were important public figures from the 1890s onward, but Taft was by far the more prominent.

In fact, Taft remains to this day a uniquely successful accumulator of high offices in the federal government. He is the only person ever to hold the highest executive office in the United States (he was president from 1909 to 1913) and the highest judicial office (he was chief justice from 1921 to 1930).23 Day’s highest executive and judicial positions were secretary of state (1898) and associate justice (1903–22)24 — all of which would be impressive when compared to anyone’s career other than Taft’s.25 And so it should come as no surprise that Taft, who loomed so much larger than Day in person and in office in their own time (and in history books ever since), should also be more easily noticed for his baseball associations.

Nevertheless, there is little evidence, other than occasional and unsubstantiated journalistic froth,26 that Taft’s interest in baseball was anything more than friendly, polite, and dutiful. By all appearances, he was sometimes involved with the game, but never in love with it. His four famous involvements with baseball reflect this fairly detached relationship.

First and most famously, on April 14, 1910, he became the first president of the United States to toss the ceremonial first pitch on opening day at a major-league game.27 The moment came as a surprise to Taft (an odd reaction, in light of the fact that plans reportedly had been made for the same stunt at the opening of the 1909 season):28

President Taft, provided with pass No. 1, today enjoyed the novel experience of seeing the Washington American league team win a ball game. …

Last year, the executive saw Washington play Boston, late in the season, but the local players got stage fright when the president arrived and threw away the game. Mr. Taft remarked then that he must be a “hoodoo” and remained away from the ball park the rest of the season. . . .

The president took an active part in the game. Just before play was started, Umpire “Billy” Evans made his way to the Taft box in the right wing of the grand stand, and presented the chief magistrate with a new ball.

President Is Surprised.

The president took the ball in his gloved hand as if he were at a loss what to do with it [seemingly unaware of a Washington baseball tradition in which an official of the District of Columbia government threw out the first pitch of the Senators’ major league season29 until Evans told him he was expected to throw it over the plate when he gave the signal. …

The president watched the players warm up, and a few minutes later shook hands with the managers, McAleer and Mack.When the bell rang for the beginning of the game, the president shifted uneasily in his seat, the umpire gave the signal, and Mr. Taft raised his arm.

Catcher Street stood at the home plate ready to receive the ball, but the president knew the pitcher was the man who usually began business operations with it, so he threw it straight to Pitcher Walter Johnson.30

Taft would later reprise his performance,31 and his successor Woodrow Wilson would continue the practice.32 Now it is a national tradition, and a yearly opportunity to remind baseball fans that Taft was one of their kind.33

Taft does not seem to have attended many non-opening-day games during his presidency. For the most part, news reports portray him putting in appearances at games connected with official functions — during a visit to Princeton to receive an honorary degree, for example34 — and therefore perhaps unavoidable.

This cool, official-capacity interest in baseball might be an accurate portrayal, or it might be the product of incomplete coverage by journalists (unlikely, when the subject is the president of the United States) or of imperfect research by the author (surely more likely). It is supported, however, by news coverage of Taft’s relationship with baseball before and after the end of his term as president in March 1913. Compare the following hostile story in the Montgomery Advertiser about Taft’s presidential enthusiasm for baseball with the subsequent friendly but nevertheless devastating report in the Washington Post about Taft’s actual (and minimal) engagement with baseball post-presidency.

From the Montgomery Advertiser (March 3, 1913):

After March 4 [President-elect Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration day], it’s going to be the real thing to be numbered among the faithful as a baseball bug in the national capital. For the first time in the history of the United States, the three big men of the nation will be men who understand and enjoy the national pastime.

During the last administration, the lamented Vice-President Sherman was a real baseball fan, while Chief Justice White of the Supreme Court never missed a game when baseball did not interfere with his duties.

President Taft often visited the ball lot, but he did it only on state occasions when his managers thought it good politics. He would toss the ball on the field at the opening game with a stage Taft smile. When he visited Chicago, he would generally visit the Cub[s’] ball park, for be it known that Charley [Taft’s brother, Charles P. Taft] is largely interested in [that is, has a financial interest in] the Cubs and the presence of the President meant a big throng and additional dollars to brother Charles.

He attended another historic game in Pittsburgh, but that time again the Cubs were playing and as before it meant sesterces to the fond relative who has financed all of the Taft campaigns.35

Anyone who has seen Mr. Taft in the grand stand readily recognized that he enjoyed a baseball game about as much as an undertaker does a christening. He would applaud at the right time, when nudged by some political and baseball adviser. He would stretch at the opening of the “lucky” seventh, again being nudged by the afore-mentioned baseball and political adviser, but he always had the appearance that he would lots rather be in juxtaposition to a big steak with all the trimmings, with a napkin tucked under his chin.36

And, then, three months after Taft had left the White House, from the Washington Post (June 7, 1913):

Mr. Taft confessed that he had not kept in as close touch with baseball “as a good fan should,” adding that he had been following the college teams more closely than the professionals. He thought, however, that he recalled that New York was at the head of one league, while Cincinnati was at the bottom. He inquired if “[Walter] Johnson was still pitching as good ball as ever,” and when told that he had lost a few games, remarked: “They must be getting on to him.”37

In the years after he left the presidency, Taft did in fact watch some baseball at his alma mater and employer (he was a law professor at Yale from 1913 until he was appointed chief justice by President Warren G. Harding in 1921), but perhaps not much. News reports of his attendance at Yale games are few and far between.38 His sporadic attendance at those games is reflected in a 1919 news story about a Yale commencement-day game against Harvard seen by Taft, “who found his two-seat-in-one location [recall Taft’s size] in the grandstand just where he left it years ago.”39

However unkind Taft’s critics might have been about his reasons for visiting major-league parks while he was president, his own behavior once he left office lent those unkindnesses a ring of truth.

Second, Taft had a close family connection to baseball. His brother Charles P. Taft had financial interests in Major League Baseball,40 including a variety of transactions, involving the Chicago Cubs during the early nineteenth century, that rose, at one point, to majority ownership of the club (from 1914 to 1916).41 Brother William became a Cubs fan of a sort.42 Wouldn’t you, if your brother owned a major-league team?

The combination of those first two involvements in baseball, accompanied perhaps by rumors of his support for the reserve clause,43 probably led to Taft’s third involvement. In November 1918, owners of the American League and National League teams offered Taft the job of commissioner of Major League Baseball.44 Taft’s response was not enthusiastic and, in the end, nothing came of the proposal.45

Fourth and finally, there was the Federal Baseball case. As chief justice, Taft presided over oral argument of the case on April 19, 1922.46 As the senior member of the Court in the majority, he was responsible for either writing the Court’s opinion himself or assigning it to another member of the majority.47 He assigned it to Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes (a man with no interest in any sports, including baseball),48 who wrote a telegraphic, dispassionate opinion. And again as chief justice, Taft presided over Holmes’s announcement of the decision in the case on May 29, 1922.49 That is all there is for Taft and Federal Baseball. And that is pretty much all there is for Taft and baseball more generally.

In sum, once he turned the presidency and the associated opening day duties over to Woodrow Wilson in 1913, Taft’s involvement in baseball pretty much dried up, as did newspaper coverage associating him with the game — except for stories about his brother Charles’s baseball interests and his Court’s handling of the Federal Baseball case.50 This was not because Taft had lost interest in sports or because the press had lost interest in Taft and his interest in sports.

Rather, it was because Taft was devoting his leisure time to his one true sporting love: golf, a game he had picked up in middle age in the late nineteenth century.51 Taft played at every opportunity throughout his long years of public service and teaching and well into his old age, giving it up only when ordered to do so by his doctors.52 Even then he took at least one more ceremonial swing, long after he had given up baseball ceremonies.53 Coverage of his golf outings and love of the sport continued to and through his dying day.54

William Howard Taft had many redeeming qualities,55 but commentators who include a wild and enduring enthusiasm for the national pastime among them are exaggerating (although he undoubtedly enjoyed a good baseball game).56 He was indeed a true sports fanatic. Of golf. With respect to baseball, he was a casual and dutiful sometime fan, an occasionally friendly follower.

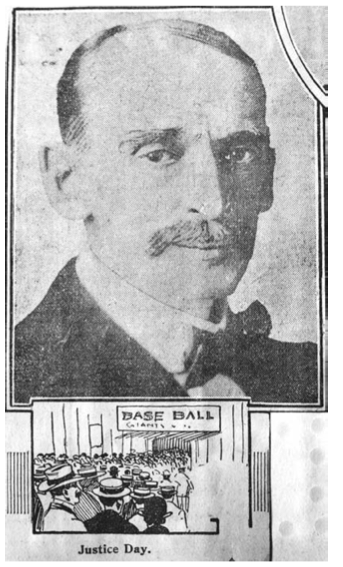

Justice Day developed a reputation as the Supreme Court’s most avid and knowledgeable baseball fan. During the World Series, he would arrange to have a page provide him with inning-by-inning updates.

WILLIAM R. DAY, THE PERSONAL-CAPACITY FAN

After the stories of Taft and baseball, William R. Day’s engagement with baseball might at first glance seem trivial. He did not inaugurate the presidential first-pitch tradition, no one in his family ever owned a major-league team, he was never offered the commissionership, and he neither presided over nor wrote an opinion in an important baseball case. Nevertheless, Day does deserve to be considered the First Fan of Baseball on the Supreme Court because he demonstrated his love for the game in both his professional and his personal life.

Compare, for example, Day’s role in the creation of a baseball tradition with Taft’s. As we have seen, Taft was president in April 1910, when others (just who those others were is uncertain)57 arranged for the president to throw out the first pitch of the Major League Baseball season at Griffith Stadium.58 Taft appeared and performed in public, to great acclaim and annual recollection down to the present.59

In contrast, Day was a justice of the Supreme Court in October of that year, as the major-league season was drawing to a close. He was on the bench, hearing oral argument in Washington, D.C., while the World Series was being played. His response suggests a genuine interest in arranging his professional life to accommodate his love of baseball, even at some cost to his own dignity, and even the dignity of the Court:

Justice Day is perhaps the one real baseball fan on the bench. Justices White and McKenna go in for it mildly but Justice Day laments that to sit on the bench never seems so difficult as when there is a game in Washington. Ordinarily in such cases he contents himself with reading about the game when court has adjourned but when the world series was on, he could not resign himself with such patience. While the court was sitting he signalled a page every little while and whispered the direction in his ear: “Find out what the score is.”

This became so frequent that the court officials decided to keep the Justice posted from inning to inning.60

Similar reports appeared in the press during the 1912 World Series:

There was diversion in the session of the United States Supreme Court this afternoon. The Chief Justice and the Associate Justices were listening to argument in the case of the Government against the Bathtub Trust. But there was just a suspicion of uneasiness or distraction on the part of the court — something that suggested expectancy or keen interest in matters not connected with bathtubs or the Sherman antitrust law.

The court page entered the judicial chamber with some show of excitement, and, hurrying to the bench, handed a slip of paper to Associate Justice Day. It was evident that the Bathtub Trust was forgotten by the Justices as the slip of paper was passed down the line. In groups of two or three the distinguished jurists of the highest court in the land leaned over the paper and read eagerly what was written on it.

This diversion happened at intervals throughout the session of the court. Then it came out that for the first time in its history the Supreme Bench was getting bulletins of a baseball game. [Obviously, the Times reporter had not been in the courtroom in 1910.] Justice Day, the foremost fan on the court, made arrangements for the bulletin service. The progress of the final match in the world’s series was made known to the court inning by inning.61

Interviewed many years later for a biography of Day, his son Rufus told a similar story.62

Later coverage of these episodes, and their steady identification of Day as the instigator and organizer, suggests that at least during Day’s tenure on the Court such updates became a tradition and even that reporters themselves were sometimes the sources of Day’s on-the-bench reports.63

So it should come as no surprise that, when Day announced his retirement in 1922, newspaper coverage included descriptions of his enthusiasm for baseball and highlighted his World Series tradition. For example:

A baseball fan of the first calibre[,] Justice Day has always found time to follow the game. He knows the big league players by name, keeping up to the minute on their batting averages, and while he never has permitted his fondness for the play to interfere with his judicial duties he frequently has hurried from the court to the ball park as soon as he could lay aside his robe, and during the world series has always kept advised upon the bench of the progress of the game, play by play.64

After Day’s death in 1923, news coverage and obituaries featured similar reports. For example:

Justice Day had one hobby. It was baseball. Few games did he miss when business would permit him to attend. Even on the bench, it was his custom to receive the reports of the baseball games by innings during most serious deliberations. It is said that the justice would have a clerk learn the progress of the game and write it on a slip of paper. This a page would lay on the desk. After Justice Day had glanced at it, he would pass it on to his colleagues.65

And:

Justice Day was a dyed-in-the-wool baseball fan. . . . During the world series he always arranged to keep advised of the contests, having telegraphic reports play by play passed to him upon the bench. These he read with keen interest and as he passed them along the bench to his colleagues he would add some criticism upon the progress of the contest.66

After Day’s death, the tradition of on-the-bench World Series updates seems to have lapsed.67 At least there are no more news stories about it, other than an occasional reference to its existence in the past.68 Which invites the obvious conclusion: The establishment and lifespan of this tradition were purely a product of Day’s love for the game. It was created by him, led by him, and expired with him.69 The same cannot be said of Taft and the first-pitch tradition.

What little we know of Day’s work as a justice off the bench also suggests a fan’s preoccupation with the game. For example, among his papers at the Library of Congress is a 1912 letter to his colleague Charles Evans Hughes, who joined the Court in 1910. Apparently, Hughes forwarded to Day an application for some sort of writ (in this context, a request by someone for an order to be issued by a justice of the Supreme Court) that had initially been submitted to Hughes.

Lacking both Hughes’s cover letter and the application itself, we cannot know what it was all about, but we can be pretty sure that it did not involve the infield-fly rule. Day’s reply to Hughes does invoke the rule nonetheless:

March 19, 1912

My dear Judge:

My mail last evening brought to me the reference of the enclosed communication.

As the application is to you as “Ex-Governor,” I must respectfully decline to grant the writ. My own opinion is that the writer is a victim of too close study of the somewhat complicated rules and procedure concerning infield flies.

If you think I have not properly acted on this application there is precedent for referring it to the court for action by a full bench.

Faithfully yours, William R. Day70

The Baseball “Crank.”

When Day joined the Supreme Court in 1903, he was already known as an avid baseball fan.71 Even in his early years on the Court, reports of his appearances at games reflected a journalistic awareness of his routine attendance, which in turn reflected an interest on Day’s part that extended beyond opening days, World Series, and other especially spectacular games. For example:

Mr. Justice Day, of the United States Supreme Court, was in his accustomed seat back of the home team’s bench and rooted with his usual vigor for the Nationals. He was accompanied by several ladies.72

And:

No one enjoys baseball more than Mr. Justice Day, of the Supreme Court. He is a regular spectator and yesterday induced Mr. Justice Harlan to lay aside his golf sticks and attend the game. “Is that gentleman in blue who says ‘tuh’ the chief justice of the game?” asked Mr. Harlan of his colleague.

“Yes,” responded Mr. Day, “and if any of those players attempt to argue with him he will point his finger toward the bench and out of the game he will go.”73

And:

Justice Day is probably the best posted on the national game of any of his associates on the Supreme bench, for he has played it [a likely inaccuracy discussed below], and never misses an exhibition when he is in the city, and a ball game is advertised.74

As the years passed, reporters picked up on another, larger pattern in Day’s baseball-viewing habits: “Justice Day will remain in Washington, a devotee of baseball, until mid-summer when he will go to Mackinac [in northern Michigan, where he rented a cottage every year for the Day family’s summer vacation].”75

Of course, Day wasn’t staying in Washington just for the baseball and the fine weather. He had work to do.76 But that didn’t keep him away from the ballparks during the early summer months, as the datelines on many Day-related baseball stories show.

The news coverage of Day’s attendance at games over time also reflected journalists’ awareness of Day’s deep enthusiasm for and knowledge of the game. Referring to him as “The Court’s Real Baseball ‘Crank,’”77 the New York Times described Day’s baseball persona in 1910:

Mr. Justice Day, President Roosevelt’s first selection for the Supreme Court, is the baseball “fan” par excellence of the court. While Justices White and McKenna never miss a game if they can help it, Justice Day is a real baseball “crank.” He knows as much about the rules of the game as he does about the rules of the Supreme Court itself, and he knows practically all the players in the big league clubs, not only by name and reputation, but by sight. When the schedule of the Supreme Court comes into conflict with the schedule of the Washington ball team, Justice Day attends the performance of the former under dire protest. If he can possibly arrange to get away, he will shed his judicial robes without further ado, and hie himself away to a grand stand seat, where he can pass judgment on the chasers of the baseball, rather than on the merits of arguments of lawyers engaged in shadowing the Constitution.78

And as the Portland Oregonian reported in 1907, “He is 58, slight, also retiring and silent unless he is witnessing a baseball game.”79

Evidence relating to the place of baseball in Day’s early years and in his family life is truly sparse. What little there is points to an interest in baseball that dated back to his youth and that in adulthood he shared it with his sons. His files at the Library of Congress contain correspondence in which he “admit[s] having been interested in baseball during my college life, — an interest which I still retain,”80 and a letter from his son Luther reveals an ongoing interest in the performance of the baseball team in Day’s hometown of Canton, Ohio.81 A Washington Post story places Day at a Georgetown–Princeton game with his son Rufus.82

Strangely, Day’s long, passionate, and public love affair with baseball was not in his own time and is not now commonly associated with the outcome of the Federal Baseball case. No one singles out Day the passionate baseball enthusiast, accusing him of voting for the antitrust exemption because he was biased in favor of the baseball establishment in all its traditional, collusive, reserve-clause glory. This is in notable contrast to the abuse heaped on Taft and Holmes for Federal Baseball (recall that Holmes wrote the opinion for the Court),83 and, more recently, on Justice Harry A. Blackmun,84 the author of the opinion for the Court in Flood v. Kuhn — the most recent decision upholding the baseball antitrust exemption.85

Exploration of the reasons for this odd neglect of Day (treatment surely gratifying to him, wherever he is) are beyond the scope of this article. But one possibility comes easily to mind: Day was the only one of the four whose involvement in baseball was limited to fanatically keeping up with the players and the games. He was just a fan.

POSTSCRIPT: PLAYERS?

One aspect of baseball does seem to have been beyond the reach or interest of both Taft and Day: competitive play. It sometimes happens, however, that celebrities in the full flower of their fame receive credit they do not deserve for youthful accomplishments that never happened. This may be the case with Taft and Day and baseball.

Taft Did Not Play Third for Yale

Numerous modern reports — most citing Andrew Zimbalist’s book Baseball and Billions: A Probing Look Inside the Big Business of Our National Pastime (1992) — place Taft at third base on the Yale baseball team during his college years in the mid-1870s,86 usually in the context of some sort of critique of the Federal Baseball case and Taft’s position as head of the court that decided it. Zimbalist writes of Federal Baseball that it was decided by “a court headed by former President William Howard Taft, himself an erstwhile third baseman at Yale University.”87 Zimbalist provides a footnote to The Imperfect Diamond: A History of Baseball’s Labor Wars (1980), by Lee Lowenfish and Tony Lupien. Unfortunately, Lowenfish and Lupien provide no support for their claim.

Zimbalist makes the same claim in his 1994 article “Baseball Economics and Antitrust Immunity,” this time with a footnote to the Supreme Court’s Federal Baseball opinion, which says nothing at all about Taft or Yale baseball.88 In other words, neither Lowenfish and Lupien nor Zimbalist provide evidence to support the claim that Taft played third at Yale. Neither do authors who reproduce the story, with or without credit to Lowenfish and Lupien or to Zimbalist.89 Apprised of the error, Lowenfish has corrected it in the third edition of The Imperfect Diamond (Nebraska, 2010).

Concrete proof of participation in interscholastic athletics in the nineteenth century can be hard to come by, except for those stars whose names appeared in newspapers at the time, making it practically impossible to prove a negative. But in Taft’s case the very extremity of his celebrity in adulthood generated some pretty convincing evidence that he was never on the Yale baseball team.

When Taft ran for president in 1908, he was the subject of puffy presidential-campaign biographies. These are just the sort of publication that could be expected to make the most of every accomplishment or shred of evidence that might support a maximally inflated account of an accomplishment in the candidate’s life. Yet here is what the semiofficial William Howard Taft: The Man of the Hour (it featured an introductory chapter by Taft’s sponsor, President Theodore Roosevelt) said of Taft the boy: He was a good play-fellow, a bit too slow moving for a first class captain of baseball, but a master swimmer, and pioneer of the ‘plumping’ game at marbles.90

And when he reached Yale in 1874:

The photographs taken of him then show a clean-cut youngster, solid but not fat, with a figure which showed power in every line. He was hailed by his classmates as a certain champion in athletics, and the football enthusiasts received him as a tower of strength for the team. But Taft did not go in for athletics. He was in college for the sake of an education, and he meant to make the utmost of his opportunity. . . . He joined in the play of his fellows, worked in the gymnasium, wrestled, and played football a little. But his athletics were for exercise and recreation, not a means of winning honor or reputation.91

Similarly, here is what Robert Lee Dunn writes in his William Howard Taft: American about Taft’s career in college sports:

He showed prowess in various individual contests, especially in wrestling. He did not join any of the ’Varsity teams, though once he was anchor in a tug of war. His father had sent him to Yale to study and the young man sought to win honors in scholarship as Judge Taft [his father] has done in the same college before him.92

Hardly ringing claims, or even feeble ones, of baseball prowess. Taft, it seems, was a big nerd, and proud of it. And to the extent he was even willing to play sports, baseball was not a candidate.

Day Probably Did Not Play for Michigan

Claims about Day and a collegiate baseball career are neither as recent nor as specific as they are for Taft. Still, they too exist, and they too are unaccompanied by supporting evidence.

In the years following Day’s appointment to the Supreme Court, much was made of his intense interest in baseball.93 For some newspapers at the time, this extended to reports that Day “was educated at Ann Arbor [the University of Michigan], where he was a member of the baseball team and noted as a sprinter.”94 Alas, those reports did not quote anyone or cite any sources for Day’s collegiate athleticism.

More plausible is the New York Times’s report on Day’s death in 1923:

Justice Day’s health was never good. … He was of slight physique, and never took part in any games or sports. But he made up for this lack by his undisguised pleasure in watching big league baseball games.95

His biographer, who enjoyed the cooperation of Day’s family, friends, and former colleagues on the Court,96 writes, “Of his student days at Ann Arbor little has been recorded. Incidents, however, have been reported. …” Unfortunately, none of those incidents appears to have had anything to do with sports.97

Evidence relating to the place of baseball in Day’s early years amounts to very nearly nothing. The only clue I have found is the 1912 letter, in his files at the Library of Congress, in which he “admit[s] having been interested in baseball during my college life, — an interest which I still retain.”98 Maybe there is some better evidence, somewhere else, that Day played for Michigan.

POST-POSTSCRIPT: TRADITIONAL RENEWAL

The baseball tradition with which Taft is associated in his official capacity as president — the first pitch — remains vibrant.99 The tradition with which Day ought to be associated in his personal capacity as a baseball fan who happened to work at the Supreme Court — the on-the-bench update — died with him.100 But Day’s tradition has been revived, at least once, briefly.

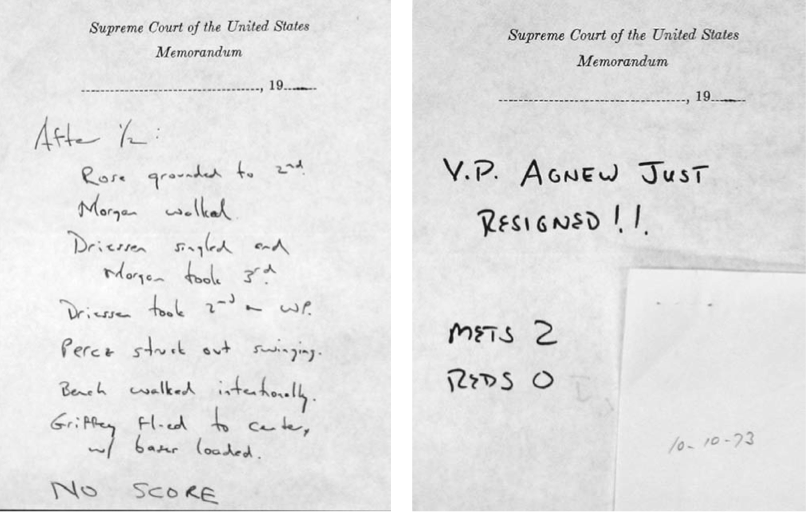

Justice Potter Stewart, who served on the Supreme Court from 1958 to 1981, was a baseball fan, and a Cincinnati Reds fan in particular.101 The Reds and the New York Mets played for the National League championship in early October 1973. In his article “Court of Dreams” (2005), Skip Card quotes Terry Perris, one of Stewart’s clerks, and an assignment Stewart gave his clerks that October:

He had asked us to keep tabs of the score of the Reds–Mets game while he was on the bench and we were at our desks doing our work, and to send into him via one of the pages half-inning reports of the score of the game. We did that throughout the playoffs while the Court was in session.102

Most of those half-inning reports are probably either lost to history or locked up in Stewart’s sealed papers at Yale University.103 But a series of three notes from the Reds–Mets game of October 10, apparently passed along the bench from Stewart to his colleague Justice Harry Blackmun, are preserved in Blackmun’s files.

In October 1973, Justice Potter Stewart, a Reds fan, assigned his clerks the task of sending a page in with an update every half inning during the NLCS between the Reds and Mets.

According to Card, the first note is in the handwriting of Fred Davis, another Stewart clerk, and the second and third notes are in the handwriting of Andy Purvis, yet another Stewart clerk. The date on the second note is in Blackmun’s handwriting.104

Stewart and Blackmun passed each other notes about baseball for several years after that,105 including at least one exchange in October 1975 that appears to record a World Series wager and mark its payout.

Who knows what else might turn up when Stewart’s papers are eventually unsealed?

One thing should be obvious, though: Taft and Day are long gone, but baseball fandom on the Supreme Court lives on.

ROSS E. DAVIES is professor of law at George Mason University and editor of “The Green Bag: An Entertaining Journal of Law.”

Notes

1 259 U.S. 200 (1922); see, e.g., Paul Finkelman, “Baseball and the Rule of Law Revisited,” 25 T. Jefferson L. Rev. 17, 29 (2002); Thomas R. Hurst and Jeffrey M. McFarland, “The Effect of Repeal of the Baseball Antitrust Exemption on Franchise Relocations,” 8 DePaul–LCA J. Art & Ent. L. 263, 267 (1998); cf. Robert M. Jarvis and Phyllis Coleman, “Early Baseball Law,” 45 Am. J. Legal Hist., 117, 117 n. 2 (2001).

2 259 U.S. iii.

3 See, e.g., “Eldon L. Ham, The Immaculate Deception: How the Holy Grail of Protectionism Led to the Great Steroid Era,” 19 Marq. Sports L. Rev., 209, 217 (2008); Larry C. Smith, “Beyond Peanuts and Cracker Jack: The Implications of Lifting Baseball’s Antitrust Exemption,” 67 U. Colo. L. Rev., 113, 117 (1996); Willis D. Gradison Jr., “Remarks for Dedication and Public Opening of the William Howard Taft Birthplace,” 134 Cong. Rec. E3016-04 (20 September 1988).

4 See, e.g., Mahn v. Harwood, 112 U.S. 354 (1884); Stuart v. Hayden, 169 U.S. 1 (1898); Davis v. Coblens, 174 U.S. 719 (1899); McNichols v. Pease, 207 U.S. 100, 107 (1907); see also Appellant’s Reply Brief at 5, Weber v. Freed, 239 U.S. 325 (1915); Slocum v. Brush, 140 U.S. 698 (1891); “May Now Pay the Penalty,” New York Times, 12 May 1891, 3; Keith v. Kellam, 35 F. 243, 244 (C.C.D. Kan. 1888) (Brewer, J.), rev’d, 144 U.S. 568 (1892); Commonwealth v. Watson, 154 Mass. 135 (1891) (Holmes, J.); Schmalstig v. Taft, 10 Ohio App. 285 (Ohio App. 1. Dist. 1919).

5 “Second Game Cut Short,” Washington Post, 8 October 1905, S1; “Capital Is Thrilled as Wires Flash ‘Pennant Is Won,’” Washington Post, 30 September 1924, 1, 4.

6 Compare 259 U.S. iii, with Members of the Supreme Court of the United States, http://www.supremecourtus.gov/about/members.pdf (accessed 23 November 2009).

7 Francis A. Allen and Neil Walsh Allen, A Sketch of Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson, 5, 8–11, 22, 97 (2005).

8 Skip Card, “Court of Dreams,” N.Y. State Bar J. 11 (March–April 2005).

9 Flood v. Kuhn, 407 U.S. 258 (1972); The Justice Harry A. Blackmun Oral History Project 18, 184–85 (Supreme Court Historical Society and Federal Judicial Center, 1994–95).

10 Tony Mauro, Major Milestone, Legal Times, 2 May 2005, 4.

11 Ben Walker, “Supreme Court Justice Trades Robe for Jersey,” [Mobile, Ala.] Press-Register, 11 March 2007, B6.

12 Joan Biskupic, “Sotomayor to Make Her Pitch for Yanks,” USA Today, 23 September 2009, 4C.

13 Members of the Supreme Court of the United States, http://www.supremecourtus.gov/about/members.pdf (accessed 23 November 2009).

14 Justice White’s Career, Washington Post, 12 December 1910, 2.

15 “Treaty Story a Myth,” Chicago Daily Tribune, 6 June 1897, 4. Harlan may be the only sitting justice to have umpired a baseball game. See “Cathedral Has Foes,” Washington Post, 21 May 1905, 11.

16 “Wild Scenes by High Officials When Game Is Won in Grand Rally,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 19 June 1912, 12.

17 “Wilson in Princeton Festivity,” Trenton [N.J.] Evening Times, 13 June 1914, 1; “Pitney A Baseball Star,” [Pawtucket, R.I.] Evening Times, 22 February 1912, 7.

18 Just look at what’s been done with presidents. See William B. Mead and Paul Dickson, Baseball: The Presidents’ Game (1993).

19 See, e.g., “Our Presidents as Cartoon Subjects,”Chicago Daily Tribune, 17 August 1923, 1; “A Wilson Dollar,” Wall Street Journal, 30 December 1918, 2; La Marquise de Fontenoy, Chicago Daily Tribune, 31 March 1916, 6; see also Robert B. Highsaw, Edward Douglass White: Defender of the Conservative Faith, 59 (1981).

20 See, e.g., letter from John Marshall Harlan to William R. Day, 22 September 1906, in Papers of William R. Day, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, box 21 (“If Taft would sit down on the Cuban insurrectionary leaders, all trouble would cease, and it would not be necessary to invoke the authority of the Territorial Clause”); Herbert S. Duffy, William Howard Taft, 162 (1930).

21 David J. Danelski and Joseph H. Tulchin, eds., The Autobiographical Notes of Charles Evans Hughes, 170 (1973).

22 See, e.g., “Justice Day’s Giant Son,” Atlanta Constitution, 5 December 1915, D8 (Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes describing Day’s tall and husky son William Jr. as “a block off the old chip”).

23 David T. Pride, “William Howard Taft,” in The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1993, ed. Clare Cushman, 341–45 (1993).

24 Kathleen Shurtleff, “William R. Day,” in The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1993, ed. Clare Cushman, 291–95 (1993).

25 Both men held other high offices, and they did have one position in common: Both served on the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, Taft from 1892 to 1900, and Day from 1899 to 1903. See “Taft, William Howard,” and “Day, William Rufus,” in Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, http://www.fjc.gov/public/home.nsf/hisj (Federal Judicial Center, accessed 21 November 2009).

26 See, e.g., “Capital Is Thrilled as Wires Flash ‘Pennant Is Won,’” Washington Post, 30 September 1924, 1, 4.

27 Taft Pitches First Ball, Chicago Daily Tribune, 15 April 1910, 13; see also Ronald G. Liebman, “Walter Johnson’s Opening Day Heroics,” 10 The Baseball Research Journal, 53 (1981); William B. Mead and Paul Dickson, Baseball: The Presidents’ Game, 24 (1993).

28 “Taft to Toss Ball,” Boston Daily Globe, 12 April 1909, 5.

29 “Taft Tosses Ball,” Washington Post, 15 April 1910, 2; Steve Wulf, “Ball One: On Opening Day in Baltimore, Bill Clinton Threw Out the First Pitch, Continuing a Grand American Tradition That Began with Presidents and Has Gone On to Include Actors, Animals and Cartoon Characters,” Sports Illustrated, 12 April 1993, 84; Harvey W. Crew et al., Centennial History of the City of Washington, D.C., 159 (1892).

30 Taft Pitches First Ball, Chicago Daily Tribune, 15 April 1910, 13; see also http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1910/VWS101910.htm.

31 “President Taft Out with Fans,” Chicago Daily Tribune, 13 April 1911, 21; “Ball Pass for Wilson,” Los Angeles Times, 11 March 1913, 11.

32 “Wilson and Cabinet Attend Ball Game,” New York Times, 11 April 1913, 1; see also John Milton Cooper Jr., Woodrow Wilson: A Biography, 258 (2009); William B. Mead and Paul Dickson, Baseball: The Presidents’ Game, 24 (1993).

33 Joshua Fleer, “The Church of Baseball and the U.S. Presidency,” 16 Nine, 51 (2007); see, e.g., Mike Dodd, “President Lobbs One Up for Tradition,” USA Today, 15 July 2009, 4C; James C. Roberts, “Change-up We Can Believe In: A Century of Baseball by Members of Congress,” Washington. Times, 23 June 2009, B2; Paul Duggan, “Bush Skips Ceremonial First Pitch Tradition,” Washington Post, 2 April 2007.

34 “John Grier Hibben Pres. of Princeton,” Charlotte [N.C.] Daily Observer, 12 May 1912, 1 (Taft and Chief Justice Edward D. White see Princeton– Cornell game).

35 This is probably a reference to the Cubs’ 8–3 victory over the Pittsburgh Pirates on May 29, 1909. See “Taft Quits Yale Men to See Ball Game,” New York Times, 30 May 1909, 1; “Taft Off to Make Gettysburg Speech,” New York Times, 31 May 1909, 3; http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1909/05291909.htm (accessed 21 November 2009).

36 Fuzzy, “Fanning by the Fireside,” Montgomery [Ala.] Advertiser, 3 March 1913, 7.

37 “Back with Big Smile,” Washington Post, 7 June 1913, 1.

38 See, e.g., “Yale Defeats Harvard Men,” Los Angeles Times, 18 June 1913, § 3, 1; “Contests at Yale Are Halted by Rain,” New York Times, 20 June 1928, 28. And this despite the fact that his son played for and later coached Yale baseball. “Live Tips and Topics,” Boston Daily Globe, 17 April 1915, 4; “A. L. Knapp, Taft to Coach Yale Nine,” Washington Post, 24 January 1919, 4.

39 Melville E. Webb Jr., “Prann’s Hit in Ninth Beats Harvard, 2 to 1,” Boston Daily Globe, 18 June 1919, 7.

40 See Lenny Jacobsen, Charles Murphy, in The Baseball Biography Project, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/e707728f (Society for American Baseball Research, accessed 21 November 2009); Alfred Henry Spink, The National Game, 294 (2d ed. 1911); Harold Seymour, Baseball: The Golden Age, 31, 36 (1971).

41 See “Cubs History: All-Time Rosters: Cubs Owners,” http://chicago.cubs.mlb.com/chc/history/owners.jsp (accessed 21 November 2009); “Murphy Sells Cubs; Out of Baseball,” New York Times, 22 February 1914; “$500,000 Paid for Cubs,” New York Times, 21 January 1916; “Weeghman to Pay $500,000 for Cubs,” New York Times, 6 January 1916; “Chicago Cubs Sold to C. H. Weeghman: Owner of Federal League Club Practically Closes Deal for National Team,” New York Times, 13 November 1914.

42 “Taft Quits Yale Men to See Ball Game,” New York Times, 30 May 1909, 1.

43 “Gives Players Just One Day,” Washington Post, 25 December 1913, 8; “Clubs to Enjoin Contract Jumpers,” New York Times, 29 December 1913, 5; see also “W. H. Taft Speaks at Baseball Dinner,”New York Times, 10 February 1916, 8.

44 “Ask Taft to Act as Baseball Head,” New York Times, 24 November 1918, 1; “Taft Gives Terms as Baseball Head,” New York Times, 25 November 1918, 14. Taft was probably the first but certainly not the last ex-president to be invited to help out with the administration of Major League Baseball. See, e.g., Robert McG. Thomas Jr., “Nixon to Arbitrate Umpire Dispute,” New York Times, 16 October 1985, B9.

45 “Baseball Tribunal Declined by Taft,” New York Times, 1 December 1918, 24.

46 259 U.S. at 200.

47 The decision in Federal Baseball was unanimous as a matter of law (there were no recorded dissents or concurrences), 259 U.S. 200, but it may not have been as a matter of fact. Alexander Bickel reports in his The Judiciary and Responsible Government (1984) that Justice Joseph McKenna’s confidential internal response “to Holmes’ opinion in Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore v. National League was: ‘I voted the other way but I have resolved on amiability and concession, so submit. I am not sure that I am convinced.’” Id. at 238. That is, McKenna disagreed with the Court’s decision in Federal Baseball, but he opted to keep his mouth shut, once a common practice at the Court. See G. Edward White, “The Internal Powers of the Chief Justice: The Nineteenth-Century Legacy,” 154 U. Pa. L. Rev., 1463, 1469–85 (2006).

48 See G. Edward White, “Would You Like to Do Lunch with Holmes?” 61 U. Colo. L. Rev., 737, 739 (1990). Having spent more than twenty years on the Supreme Judicial Courts of Massachusetts, Holmes could not help but have some familiarity with baseball. He participated in several baseball cases arising out of civil conflicts and state crimes, writing the opinion for the court in at least one, Commonwealth v. Watson, 27 N.E. 1003 (Mass. 1891).

49 259 U.S. at 200; “Majors Sustained in Federal League Suit for Damages,” Montgomery [Ala.] Advertiser, 20 May 1922, 5.

50 See, e.g., “Taft Here To-day on the Way to Yale,” New York Times, 22 June 1908; “Knockout of Baltimore Feds Red Letter Day for Baseball,” Sporting News, 8 June 1922, 3.

51 R. L. Duffus, “Our Chief Justice at Seventy,” New York Times, 11 September 1927, 2, 22.

52 Ibid.; “William Howard Taft Dies Quietly at Home,” Los Angeles Times, 9 March 1930, 1, 12.

53 “Justice Taft Opens Course,” Christian Science Monitor, 20 July 1925, 6; “The Chief Justice Tees Off,” New York Times, 2 August 1925.

54 See, e.g., “Chief Justice Taft 64; Entertains Hundred Friends,” Chicago Daily Tribune, 16 September 1921, 1; “Taft Takes Walk; Refuses to Be Ill,” Washington Post, 18 January 1930.

55 See generally Robert Post, “Taft and the Administration of Justice,” 2 Green Bag 2d 311 (1999); Herbert S. Duffy, William Howard Taft (1930); Alpheus Thomas Mason, William Howard Taft: Chief Justice (1964).

56 “Wild Scenes by High Officials When Game Is Won in Grand Rally,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 19 June 1912, 12.

57 Compare, e.g., Steve Wulf, “Ball One: On Opening Day in Baltimore, Bill Clinton Threw Out the First Pitch, Continuing a Grand American Tradition That Began with Presidents and Has Gone On to Include Actors, Animals and Cartoon Characters,” Sports Illustrated, 12 April 1993, 84 (crediting umpire Billy Evans), with Eldon L. Ham, “The True Meaning Behind Ozzie- gate,” Chicago Tribune, 14 February 2006, 15 (“Taft … invented the tradition”), with Ronald G. Liebman, “Walter Johnson’s Opening Day Heroics,” 10 The Baseball Research Journal, 53 (1981) (“… Taft attended, accepting the invitation of Washington Owner Clark Griffith, and began the perennial custom of the U.S. Chief Executive ‘throwing out the first ball’ at Washington openers”)

58 See notes 27–31 and accompanying text.

59 Ibid.

60 “Supreme Court Justices at Play,” Trenton [N.J.] Evening Times, 25 October 1910, 9.

61 “News in Highest Court,” New York Times, 17 October 1912, 1.

62 Joseph F. McLean, William Rufus Day: Supreme Court Justice from Ohio 63 and n.44 (1946); see also id. at 62 (“He did enjoy bass fishing, but his main pleasure was the national pastime. …”).

63 See, e.g., H. Addington Bruce, Baseball and the National Life, 17 May 1913, 104; “Foremost Statesmen of America Plain People, Going About Daily Tasks Like Less Distinguished,” Washington Post., 14 December 1919, AU4, 5.

64 “Day Quits Place in Supreme Court,” Atlanta Constitution, 25 October 1922, 1; see also, e.g., “President Accepts Day’s Resignation,” Washington Post, 25 October 1922, 5.

65 “Hughes Voices Washington Tribute to Judge Day,” Boston Daily Globe, 10 July 1923, 5; see also “Death Takes Justice Day,” Los Angeles Times, 10 July 1923, 12.

66 “Former Associate Justice Day Dies,” Atlanta Constitution, 10 July 1923, 16; see also “Death of Former Justice W. R. Day Is Mourned Here,” Washington Post, 10 July 1923, 3; “William R. Day’s Career,” New York Times, 10 July 1923, 19.

67 It is impossible to be certain about this, because the Supreme Court did not then and does not now conduct its business in front of large crowds, and because the justices, individually and collectively, have a long history of being very selective about sharing internal Court documents and news of internal Court business with journalists and the public. See, e.g., Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong, The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court (1979); David J. Garrow, “The Supreme Court and the Brethren,” 18 Const. Commentary, 303 (2001); see also, e.g., Dennis J. Hutchinson, “The Black–Jackson Feud,” 1988 Sup. Ct. Rev. 203, 206–7; “Leaky Ethics,” 8 Green Bag 2d 123 (2005).

68 See, e.g., “Quill Pens— Lest the Nation Totter!” Christian Science Monitor, 21 January 1929, 14.

69 There is some evidence that on-the-bench World Series updates were not Day’s first maneuver conceived to reconcile his commitments to work and to baseball. On July 3, 1897, while Day was serving as assistant secretary of state, the Chicago Tribune reported that “[a]ll the Assistant Secretaries” in the State Department “put up a job on Secretary [of State John] Sherman the other day so as to get off in time to see the baseball game.” The details of the stunt are not relevant here. See “To Go to a Vote Tuesday,” Chicago Daily Tribune, 13 July 1897, 12; see also “Death of Former Justice W. R. Day Is Mourned Here,” Washington Post, 10 July 1923, 3.

70 Letter from William R. Day to Charles Evans Hughes, 19 March 1912, in Papers of William R. Day, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, box 3.

71 “Justice Day and His Four Sturdy Young Sons,” Washington Times, 8 March 1903.

72 “Heard and Seen in the Grand Stand,” Washington Post, 6 May 1905, 9.

73 “Seen and Heard in the Grand Stand,” Washington Post, 10 May 1905, 9.

74 “Baseball at Washington,” San Jose [Calif.] Mercury News, 23 June 1906, magazine section, 1.

75 “Members of Supreme Court, After Eight Months Work, Are Off for a Rest,” Miami Herald, 5 July 1915, 7.

76 See, e.g., letter from William R. Day to Edward Osgood Brown, 12 June 1914, in Papers of William R. Day, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, box 3.

77 Crank, an obsolete term for a baseball fan, was in wide use during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when Day was following the game. Paul Dickson, The Dickson Baseball Dictionary, 114 (1989).

78 E. J. Edwards, “Our Supreme Court as Human Beings,” New York Times, 15 May 1910. Day was in fact Roosevelt’s second appointment to the Court. Holmes was the first. Members of the Supreme Court of the United States, www.supremecourtus.gov/about/members. pdf (accessed 23 November 2009). See also Sunday [Portland] Oregonian, 5 June 1910, § 6, 4; William E. Brigham, “The Completed Supreme Court,” Boston Evening Transcript, 21 January 1911 (contrasting Day’s “slight . . . figure” with his status as “the huskiest baseball crank on the Supreme Bench” and reporting, “They say Day knows as much about the rules of the game as of the Supreme Court itself, and his broken-hearted appearance on the bench is never more impressive than when a ball game is on and he can’t get away to attend it”).

79 “What Becomes of the Cabinet Ministers?” Sunday [Portland] Oregonian, 5 May 1907, 48.

80 Letter from William R. Day to F. D. McQuesten, 12 February 1912, in Papers of William R. Day, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, box 3.

81 Letter from Luther Day to Wm. R. Day, 20 July 1906, in Papers of William R. Day, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, box 21.

82 “Princeton, 7: G.U.,” 7, Washington Post, 27 March 1910, MS5.

83 See, e.g., notes 1–3; see also Kevin McDonald, “Antitrust and Baseball: Stealing Holmes,” 1998 J. S. Ct. Hist. 88 (discussing critiques of Federal Baseball).

84 See, e.g., Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong, The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court 190-91 (Simon and Schuster 1979); Aaron T. Walker, “Title VII & MLB Minority Hiring: Alternatives to Litigation,” 10 U. Pa. J. Bus. & Emp. L., 245, 261–66 (2007); David Greenberg, “Baseball’s Con Game,” Slate, 19 July 2002 (“The opinion—for which Blackmun would long be ridiculed—included a juvenile, rhapsodic ode to the glories of the national pastime, sprinkled with comments about legendary ballplayers and references to the doggerel poem ‘Casey at the Bat’ ”); Roger I. Abrams, “Before the Flood,” 9 Marq. Sports L.J. 307, 310–11 (1999).

85 407 U.S. 258 (1972).

86 Taft graduated from Yale University in 1878. Eldon R. James, William Howard Taft, 68 Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 676 (1933).

87 Andrew S. Zimbalist, Baseball and Billions: A Probing Look Inside the Big Business of Our National Pastime 10 (updated ed. 1994). Zimbalist has repeated this claim in print several times. See, e.g., Andrew Zimbalist, “Baseball Economics and Antitrust Immunity,” 4 Seton Hall J. Sport L., 287, 288 and n.6 (1994) (again, the footnote containing a cite to the Federal Baseball opinion); Andrew Zimbalist, “A Sporting Chance for Professional Players,” Legal Times, 23 November 1992, 25; Andrew Zimbalist, “A Sporting Competition: Reading the Signs,” The Recorder, 25 November 1992, 8; Andrew Zimbalist, “A Sporting Chance for Profes- sional Players,” Conn. L. Trib., 30 November 1992, 16.

88 259 U.S. 200 (1922).

89 See, e.g., David M. Szuchman, “Step Up to the Bargaining Table,” 14 Hofstra Lab. L.J., 265, 270, and n.26 (1996); Joshua P. Jones, “A Congressional Swing and Miss,” 33 Ga. L. Rev., 639, 646, and n.51 (1999); Roger I. Abrams, “Before the Flood,” 9 Marq. Sports L.J., 307, 309 (1999); Nathan R. Scott, “Take Us Back to the Ball Game,” 39 U. Mich. J. L. Reform, 37, 51, and n.118 (2005); editorial, Baltimore Sun, 7 January 1993, 8A; editorial, Baltimore Sun, 19 August 1994, 18A; Allen D. Boyer, “Books in Brief,” New York Times, 25 October 1998 (reviewing Roger Abrams, Legal Bases: Baseball and the Law [1998]); Dick Heller, “D.C.’s No. 1 Pitcher: 12 Presidents Have Graced Openers Here,” Washington Times, 15 April 2005, C9.

90 Oscar King Davis, William Howard Taft: The Man of the Hour, 34 (1908).

91 Id. at 39–40. The Davis biography does, however, feature a photograph of Taft playing golf. Id. at 86.

92 Robert Lee Dunn, William Howard Taft: American, 216 (1908).

93 See notes 71–79 and accompanying text.

94 “The Nine Men Who Have the Last Word,” Washington Post, 4 February 1906, SM5; see also, e.g., “Americans Whose Power Is Greatest: Personal Side of the Men Who Co[n]stitute the U.S. Supreme Court,” Sunday [Portland] Oregonian, 4 February 1906, 45.

95 “William R. Day’s Career,” New York Times, 10 July 1923, 19.

96 Joseph F. McLean, William Rufus Day: Supreme Court Justice from Ohio, 6–8 (1946).

97 Id. at 18.

98 Letter from William R. Day to F. D. McQuesten, 12 February 1912, in Papers of William R. Day, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, box 3.

99 See notes 31–33. In recent years, Supreme Court Justices—John Paul Stevens, Samuel Alito, and Sonia Sotomayor in particular—have begun to participate in first-pitch rites themselves. See notes 10–12.

100 See notes 67–68.

101 Members of the Supreme Court of the United States, http://www.supremecourtus.gov/about/members.pdf (accessed 23 November 2009). As an Ohioan, the author is obliged to point out that Day, Taft, and Stewart were all also Ohioans (although Taft, who was working at Yale at the time of his appointment, was officially appointed from Connecticut) and to speculate that there might be some metaphysical connection between the Buckeye State and baseball-related greatness on the Supreme Court.

102 Skip Card, “Court of Dreams,” N.Y. State Bar J. 11 (March–April 2005).

103 See Allison R. Hayward, “The Per Curiam Opinion of Steel,” 2006 Cato Sup. Ct. Rev., 195, 206 n.59.

104 For more on the Blackmun papers, see Linda Greenhouse, “Documents Reveal the Evolution of a Justice,” New York Times, 4 March 2004, A1.

105 Skip Card, “Court of Dreams,” N.Y. State Bar J., 11 (March–April 2005); “Notes Exchanged Between Justices During Court Proceedings,” Papers of Harry A. Blackmun, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, box 116.