‘A Disciplinarian Coach’: Jackie Robinson’s Little-Known Stint Coaching College Basketball

This article was written by Eric Enders

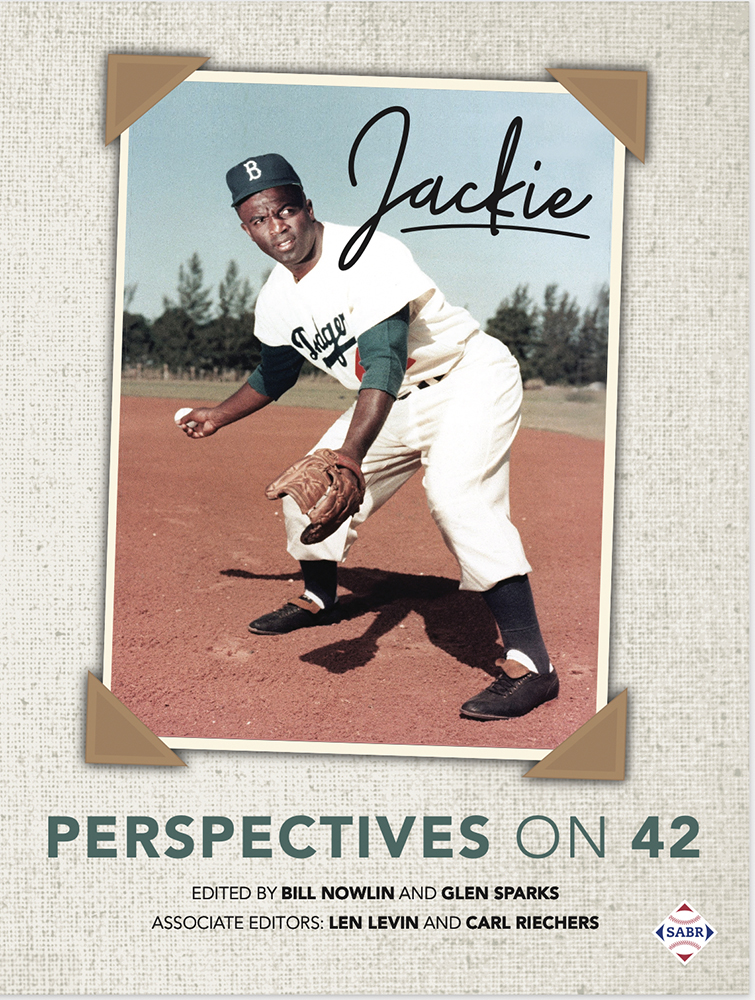

This article was published in Jackie Robinson: Perspectives on 42 (2021)

In the fall of 1944, Jackie Robinson’s life was at a crossroads. A few days after Thanksgiving, he was honorably discharged from the US Army, where he’d made headlines for refusing to move to the back of a military bus. Dismissed from his barracks at Fort Hood, Texas, he found himself with no job, no prospects, and no particular plans for the future. So he decided to pay a visit to an old friend – and before he knew it, Robinson stumbled into a new job as head coach of a college basketball team.

In the fall of 1944, Jackie Robinson’s life was at a crossroads. A few days after Thanksgiving, he was honorably discharged from the US Army, where he’d made headlines for refusing to move to the back of a military bus. Dismissed from his barracks at Fort Hood, Texas, he found himself with no job, no prospects, and no particular plans for the future. So he decided to pay a visit to an old friend – and before he knew it, Robinson stumbled into a new job as head coach of a college basketball team.

Robinson spent the winter of 1944-45 as the basketball coach of Samuel Huston College, a tiny Historically Black College (HBCU) in Austin, Texas. In a life where seemingly every moment was assiduously documented, Robinson’s stint as a college coach is perhaps the least known aspect of his biography. For one thing, basketball ranks a clear fourth on the list of sports in which Robinson achieved fame, after baseball, football, and track. For another, the tiny school where he coached, Sam Huston, no longer exists in that form, having been absorbed into another Austin HBCU, Tillotson College, as part of a 1952 merger. (The resulting school, Huston-Tillotson University, occupies the former campus of Tillotson College.)

Whatever scant records once existed were lost in the merger, and Austin newspapers in 1945 pointedly ignored athletic contests involving the tiny Black school with a shoestring budget. Few important people in Robinson’s life were around to remember the time – his fiancée, Rachel Isum, was then living in California – and Jackie himself rarely discussed the experience. As far as this author can determine, no substantive quotes or reminiscences by Robinson about his time as a basketball coach have survived. All in all, these circumstances combine to make the first half of 1945 the most recondite and difficult-to-research period of Jackie Robinson’s life.

One thing is for certain: Robinson owed his position at Sam Huston to Karl Downs, his childhood pastor and the closest thing to a father figure Robinson had in his life. The two had first met in 1938, when Downs, a tall, wiry young Texan, became the pastor at Scott United Methodist Church, which the Robinson family attended. At 25, Downs was just six years older than Robinson, and he enacted a number of programs intended to make the church more appealing to young people. “Those of us who had been indifferent church members began to feel an excitement in belonging,” Robinson later wrote.1

Downs appears to have viewed Robinson, then a young ne’er-do-well and budding gang member, as someone who could achieve great things with the proper mentorship, and he endeavored to take the teenager under his wing. “Karl Downs had the ability to communicate with you spiritually, and at the same time he was fun to be with,” Robinson wrote. “Most important, he knew how to listen. Often when I was deeply concerned about personal crises, I went to him.” Before long, Robinson was teaching Sunday school at the church, and he and Downs became close friends, spending time playing golf and other sports together.2 “He was a quiet, sweet man, someone you could talk to,” Rachel Robinson said of Downs. “Karl was the father that Jack didn’t have. Jack was so close to him. He kept saying that Karl changed his life.”3

By 1944, six years later, both men had come a long way from their days at the church in Pasadena. Robinson was now an Army veteran and a famous former athlete. Downs was now the president of Sam Huston College, a tiny Black college in Austin from which he himself had graduated a decade earlier. During his time as a soldier at Fort Hood, Robinson was a frequent presence at Downs’s Austin home, making the 90-minute trip to visit almost every weekend.4 “He’d just come down and have dinner with the president,” Harold “Pea Vine” Adanandus, the college’s athletic trainer, recalled. “And we didn’t know it at the time, but the president was also recruiting Jackie to coach the basketball team.”5

Samuel Huston College, founded in 1876, was not named after the famous Texan hero Sam Houston, but rather after an Iowa farmer who had once donated $9,000 to the school. Since being named school president in 1943, Downs had set about modernizing and expanding the struggling college, which always seemed to be teetering on the brink of bankruptcy.6 Downs enlarged its campus, tripled enrollment from 222 to 659, and brought in a series of prominent speakers and performers including Langston Hughes, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Duke Ellington. 7

Downs didn’t have a lot of money to funnel into improving the athletic department, but he did have one thing: a close friendship with one of the greatest college athletes of all time. Robinson, of course, had famously starred in four sports at UCLA, including basketball, in which he twice led the conference in scoring.8 Downs persuaded him to become Sam Huston’s director of athletics, a job that also included coaching the basketball team. “There was very little money involved, but I knew that Karl would have done anything for me, so I couldn’t turn him down,” Robinson wrote in his memoir, I Never Had It Made.9 Recalled one of Downs’s associates: “Bringing Jackie Robinson to campus was vintage Karl Downs. Nothing like that ever happened before Karl came.”10

The players and staff of the Sam Huston Dragons were thrilled with the last-minute news. “We didn’t know who our basketball coach was going to be,” Adanandus, the athletic trainer, said. “Just before the season started, he came in and went right to work.” Robinson took the job more seriously than any of his predecessors had. He instituted a physical fitness program (the school’s first) and put his own impressive collection of athletic medals on display to serve as an inspiration of sorts. “We were one of the few teams that ran at that time,” said one of the players, Roland Harden. “He got out there with us and actually showed us what to do and was a better player than anybody on our team. Or anybody we played, really. And he was a gentleman. He required us to wear suits and ties when we got off the bus.”11 Another player, D.C. Clements, recalled that Robinson “was a disciplinarian coach. He believed we should be students first and athletes second. If you cut a class or anything like that, he would put you off the team or give you some laps. He was a great coach and a great teacher.”12

With the hands-on Robinson playing in the team’s practices himself, it was obvious to everyone that the 26-year-old coach was a far better player than any of his students. “He liked to play around the basket, rebounding and all that,” Adanandus recalled. “He was tough around the basket. He was just an exceptional athlete, and you could tell he still wanted to play. He wanted to play, but he’d have to sit on the bench when we were playing those college teams.” However, Robinson was free to play as a member of the team in non-intercollegiate games – mainly scrimmages and exhibitions against nearby military teams. “We won all of [the games] when Jackie played,” Adanandus said. “We were undefeated with Jackie. Any time the team seemed to be getting behind, Jackie would have to go in.”13

The Dragons, as members of the Southwestern Athletic Conference, played an official schedule that mostly featured other HBCUs, including Prairie View College in Texas and Southern University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Their exact won-lost record has been lost to history. Observers remember the Dragons winning relatively few games, but they did manage one memorable highlight: a 61-59 upset of the defending league champion, Bishop College. Robinson, with his intense competitiveness and famously fiery temper, proved to be an intimidating force when dealing with referees. “I saw him go after officials when we were playing,” Harden said. “He didn’t get ejected, but he would go to the breaking point.”14

Late in the season, the Dragons embarked on an extended road trip, spending a month playing games across Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas. (“He would write to Rachel every day,” Harden remembered.15) When the team got home, an intriguing offer was waiting for Robinson. “Upon our return from the tour, we met up in Jackie’s office, and he was sorting his mail,” Adanandus said. “He had received a letter from the Kansas City Monarchs. He showed me the letter, and they wanted him to play ball. They offered him a $500 bonus and $250 a month. He asked me, ‘Vine, what would you do?’ I said, ‘Well, Jackie, I didn’t even know you played any baseball.’ And he said, ‘Yeah, I play a little.’”16

He was about to play a lot more. Robinson submitted his resignation to Downs, and at the end of March he reported to the Monarchs’ training camp in Houston. He performed impeccably during his brief stint in the Negro Leagues, and on August 28, he had his now-legendary meeting with Branch Rickey at Ebbets Field. In a mere six months, Robinson had gone from coaching basketball at an obscure Southern college to signing a contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers.17

After leaving Austin, Robinson made a point of keeping in touch with his former players. “We used to hear from him a lot after he left,” Clements said. “He was always sending us a letter or a card, advising us and encouraging us to continue in school.”18 Although in his later years Robinson rarely mentioned his time as a coach, he never forgot the little college that had given him his first paying job in sports. In 1968 he was named to Huston-Tillotson’s board of directors, a position he would hold until his death.19 The school buildings where he worked in 1945 are now long gone, demolished to make room for Interstate 35 and its frontage roads. The former site of Sam Huston College is currently occupied by the Lucky Lady Bingo Parlor.20

The Rev. Karl Downs, meanwhile, continued to be a vital presence in Robinson’s life after Jackie left his employ. When Jackie and Rachel got married in 1946, Downs traveled to California to perform the ceremony. When the Dodgers held a Jackie Robinson Day at Ebbets Field during their next to last home game of 1947, Downs was there to help pay tribute to his friend.21

A few months later, however, tragedy struck. Suffering from an unknown stomach ailment, Downs was rushed into emergency surgery at Austin’s segregated Brackenridge Hospital on February 26, 1948. “Rather than returning his Black patient to the operating room or to a recovery room to be closely watched, the doctor in charge let him go to the segregated ward, where he died,” Robinson wrote. “We believe Karl would not have died if he had received proper care.” Downs’s death at the shockingly young age of 35 affected Robinson enormously, and he still seemed devastated by the tragedy decades later. “It was hard to believe that God had taken the life of a man with such a promising future,” he wrote in his 1972 memoir. “Karl Downs ranked with Roy Wilkins, Whitney Young, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in ability and dedication, and had he lived he would have developed into one of the front line leaders on the national scene.”22

ERIC ENDERS is a freelance writer, editor, and former research librarian at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library in Cooperstown. He is the author of a dozen books, including Ballparks: A Journey Through the Fields of the Past, Present, and Future and Mexican-American Baseball in El Paso. His writing on baseball has also appeared in the New York Times, MLB’s World Series programs, and numerous SABR publications. A native of El Paso, Texas, he was inducted into the El Paso Baseball Hall of Fame in 2016.

Notes

1 Jackie Robinson and Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made (New York: HarperCollins, 2003), 8.

2 Robinson and Duckett, 8-9.

3 John Maher, “Huston College President Guided Jackie Robinson Down Historic Path,” Austin American-Statesman, August 24, 2013. statesman.com/article/20130824/SPORTS/308249735.

4 Eric Enders, “A Legacy Remembered: 50 Years After Jackie Robinson Shattered Baseball’s Color Barrier, Central Texans Recall His Time Here as a Basketball Coach,” Austin American-Statesman, April 15, 1997.

5 Harold “Pea Vine” Adanandus, telephone interview, March 1997.

6 Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Life (New York: Random House, 2011), 114.

7 Garner Roberts, “Abilene Man Mentor to Jackie Robinson,” Abilene Reporter-News, February 25, 2008. web.archive.org/web/20100316221705/ http://www.reporternews.com/news/2008/feb/25/no-headline—jackie_robinson-karl_downs/.

8 “UCLA Celebrates Jackie Robinson Day,” uclabruins.com, April 15, 2014. uclabruins.com/news/2014/4/15/209467368.aspx.

9 Robinson and Duckett, 69.

10 Rampersad, 114.

11 Jeff Miller, “Jackie Robinson’s Forgotten Season as a College Basketball Coach,” Bleacher Report, April 15, 2014. bleacherreport.com/articles/2004424-jackie-robin-sons-forgotten-season-as-a-college-basketball-coach.

12 D.C. Clements, telephone interview, March 1997.

13 Harold “Pea Vine” Adanandus, telephone interview, March 1997.

14 “Jackie Robinson’s Forgotten Season as a College Basketball Coach.”

15 Ken Herman, “What It Was Like Playing Basketball for Jackie Robinson,” Austin American-Statesman, September 3, 2016. statesman.com/news/20160903/herman-what-it-was-like-playing-basketball-for-jackie-robinson.

16 Enders.

17 Rampersad,114.

18 D.C. Clements, telephone interview, March 1997.

19 Maher.

20 “Jackie Robinson’s Forgotten Season as a College Basketball Coach.”

21 Maher.

22 Robinson and Duckett, 69.