A Farewell to Arms: The Major Leagues in 1968 and the Transition to a New Modern Era

This article was written by Paul Hensler

This article was published in 2008 Baseball Research Journal

By any measure 1968 was a year of upheaval. Assassinations, riots, protests, and the decision by the incumbent commander in chief to forgo a reelection bid all pointed to the unrest and instability that wracked the nation, and the bloodiest year of fighting in Vietnam did nothing to soothe the collective angst. The national pastime provided a much needed diversion from the swirling political and social turmoil during this period but was undergoing a transmogrification of its own. Throughout much of the twentieth century, Major League Baseball’s appeal to fans came from the glamour of offensive production, whether it be one swing of the bat—as with Bobby Thomson’s “shot heard ’round the world” in 1951—or season-long and career-long feats, such as Babe Ruth’s and Hank Aaron’s home runs and Pete Rose’s record 4,256 career hits. Just as good soldiers run to the sound of the guns, baseball devotees run to the crack of the bat.

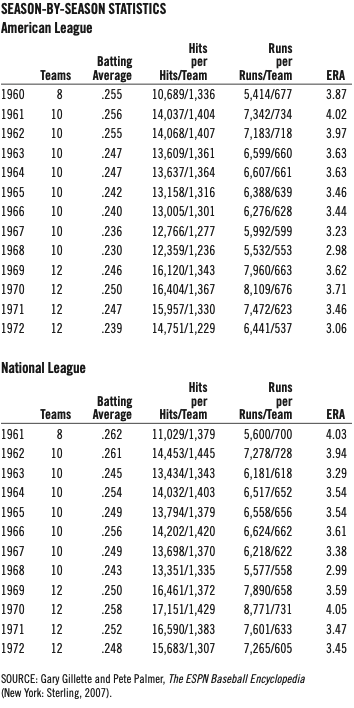

The American League experienced a small surge in offensive output after its expansion to ten teams in 1961, but the National League experienced a slight decrease in offense when it expanded to ten teams the following year. In both instances, the first post-expansion season in each league marked the high-water mark of league batting averages until the next round of expansion in 1969. National League offensive production wavered through the mid-1960s, and in 1966 it began a three-year downward trend, with a corresponding decline in league earned-run averages.

However, the figures for the American League show no such dips and rises but instead show a virtual straight-line decline in batting averages, run production, and ERA beginning in 1961 and continuing for the next seven years. Season totals for 1963 and 1964 were uncannily similar, but the general trend over the next four seasons was unmistakable: The drop in offensive output in both leagues indicated that pitching strength had gained momentum with each passing year, especially in the American League.

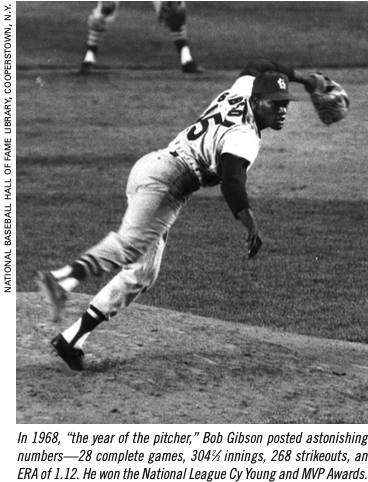

All of which leads to 1968, dubbed “the year of the pitcher,” when batting averages, hits, runs, and earned-run averages in both leagues reached low points and the season was marked by remarkable individual pitching performances.

- Three pitchers threw more than 40 consecutive scoreless innings. With his streak of 582⁄3 scoreless innings, which spanned six consecutive shutouts, Don Drysdale broke the 55-year-old record held by Walter Johnson. Bob Gibson pitched 48 2⁄3 consecutive scoreless innings, Luis Tiant 42.

- Gibson posted an ERA of 1.12, a record that still stands among qualifiers in the live-ball era. This mark had been surpassed by only three other pitchers, all of them before 1915.

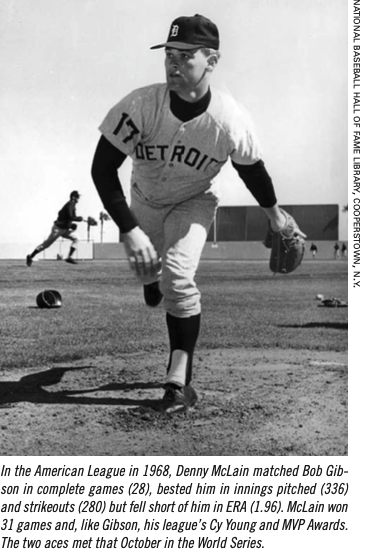

- Denny McLain won 31 games to post the first 30-win season since 1934, when Dizzy Dean went 30-7 for the St. Louis Cardinals. Given the five-man rotation that is now the rule, it may also be the last time a pitcher wins 30 games.

During spring training in 1968, Major League Baseball made an attempt to remove a clandestine weapon from the repertoire of some pitchers. Officials stiffened the penalties for use of the spitball, which had been outlawed in 1920. But over the ensuing decades many pitchers continued to throw it because “enforcement of the [existing] rule has generally been lax.”1 In 1968, the pitcher most known for throwing the spitter, or at least for being suspected of throwing it, was Gaylord Perry of the Giants. John Wyatt used Preparation H as his foreign substance of choice when loading up the ball to make his pitches dance and dart.

But more than illegal pitches were working against hitters of the era. By late May 1968, only six American League batters were hitting over .300, and fewer than ten in the National League. Writing for the New York Times in mid-June, Rex Lardner observed that Major League Baseball was reaching the point where a “‘big inning’ occurs when a team scores once.”2 If one game is to be singled out as emblematic of the dearth of run-scoring, it would have to be the contest between the New York Mets and Houston Astros on April 15, 1968. It came to a merciful conclusion in the 24th inning when the Astros scored the game’s only run, on an error by the Mets shortstop.

Yankees manager Ralph Houk—whose staff posted a team ERA of 2.79, fifth in the league and 0.13 off the league-leading Orioles and Indians—credited improved instruction at the minor-league level, which allowed pitchers to arrive in the big leagues better prepared to face opposing hitters. “Now [a pitcher] comes to the majors not only young and able to throw hard,” Houk noted, “but he’s smart and he’s got control.”3 Actually, by the late 1960s pitching coaches in the minors were generally in short supply, and Houk may have been implying that minor-league hitting instructors in the minors were not up to par.

Adding to the hitter’s plight was the increase in types of pitches a pitcher might have in his arsenal. In earlier years, a good pitcher could make do with a fastball and a curveball, but by the 1960s sinkers, sliders, and changeups had become common. “Facing two pitches, you could guess right half the time,” American League umpire Cal Hubbard observed. “With five, you don’t stand a chance.”4

And as the number of televised games increased, so too did the opportunity for pitchers to observe the competition across the league. When action was telecast from a center-field camera, the pitcher at home could view batters from the same perspective he would when he was on the mound, enabling him to note their strengths, weaknesses, and habits.

By the end of the 1968 season, the damage to major-league batting was clear. In addition to the feats of Drysdale, Gibson, and McLain, the Giants’ high- kicking Juan Marichal threw 30 complete games en route to a National League—best 26—9 record, while only three hitters in all of MLB drove in more than 100 runs. Carl Yastrzemski of the Boston Red Sox led the American League in batting with a paltry .301 average—actually, .300.5 after an 0-for-5 game in the season finale—the lowest average ever to lead the league. In each league the Most Valuable Player award went to a pitcher—to Gibson and McLain, both of whom were also unanimous choices for the Cy Young Award in their respective leagues.

On the same day that Gibson’s MVP Award was announced, the Los Angeles Dodgers unveiled plans to shorten the distance from home plate to the outfield fences at Dodger Stadium by 10 feet “as [an] aid to hitters.”5 Sportswriter Leonard Koppett doubted whether this measure would help batters because “the main problem—making contact between ball and bat—remains.”6 Whereas the step taken by the Dodgers would affect play at Dodger Stadium, the MLB rules committee was formulating a proposal that would impact every player on every team.

Much maligned as feckless in his role as commissioner, William Eckert announced a set of rules changes about two weeks before his forced resignation following the winter meetings in San Francisco in December 1968. The most notable change was that the height of the pitcher’s mound was reduced from 15 inches to 10. In consequence, as pitchers would soon experience, their lead foot would hit the dirt sooner in their delivery. As the table on page 104 suggests, by the early 1970s pitchers on the whole had begun to make the necessary adjustments to the new mound height. In addition to the lowering of the mound, the strike zone would be reduced—it would now extend, instead of from the shoulders to the knees, from the armpits to the tops of the knees.

The effectiveness of these two changes was reflected in the league batting averages, ERAs, and run production for the 1969 season. The impact was greater on the American League, where the composite batting average jumped 16 points, from a record-low .230 to .246. The rise in the National League was more modest, from .243 to .250. ERAs suffered significantly, increasing more than 0.6 runs in both leagues, from 2.98 to 3.62 in the AL and from 2.99 to 3.59 in the NL. Run production, seen as key to the objective of generating fan interest, soared, as the average per team increased by 100 runs per team in the NL and 110 per team in the AL.

At the end of the 1968 season, Major League Baseball was at a crossroads, its commissioner having been forced to resign with three years still left on his contract. Players were demanding greater leverage at the bargaining table, and Curt Flood in particular was directly challenging the reserve clause. Baseball’s status as the national pastime was in question as sports fans in increasing numbers turned their attention to the reconfigured National Football League.

Several developments in addition to increased scoring would affect the overall condition of Major League Baseball as it looked to make adjustments to enlarge its fan base. Through expansion of both leagues in 1969, MLB was able to return big-league ball to Kansas City, whose Athletics were moved by Charlie Finley after the 1967 season, and to bring big-league ball to three cities for the first time—to Seattle in the AL and to Montreal and San Diego in the NL. The two new franchises on the West Coast gave the four teams already in California more competition in their own region.

In 1968, Dick Williams was in his second season as major-league manager with Boston, and halfway through the season Earl Weaver made his debut with the Orioles. Billy Martin took over as manager for the Twins in 1969, and Sparky Anderson for the Reds in 1970. These dynamic young managers forged powerful teams that brought championship baseball to Oakland, Baltimore, Cincinnati, and New York over the ensuing decade. Especially in the case of the American League, several teams vied for supremacy after the demise of the Yankee dynasty in 1965 and gave hope to fans loyal to teams all over the map.

Bowie Kuhn, the 42-year-old Wall Street lawyer who succeeded Eckert as commissioner, left his mark on baseball in the 1970s, during which the sport grew rapidly, the conflict between owners and the players’ union intensified, and, eventually the era of free agency was ushered in. Kuhn was criticized for his “best interest of baseball” stance, and a successor would say of him that “his judgment was not sound,” although “his devotion to baseball was genuine.”7 His contributions to the game were significant. He returned voting for the All-Star game to the fans, approved the first night games (1971) for a World Series, and oversaw the expansion of the American League in 1977. Taken together, these developments increased the game’s exposure and served to broaden its reach into the sports market.

One major change that was proposed actually before 1968 and then shelved at the winter meetings in December involved a “wild-card pinch-hitter for pitchers,” which in 1973 became the experimental designated

One major change that was proposed actually before 1968 and then shelved at the winter meetings in December involved a “wild-card pinch-hitter for pitchers,” which in 1973 became the experimental designated

hitter in the American League and remains the rule there.8 After the brief spike in run production in the AL following the 1968 rule changes, it declined again, causing critics of the designated hitter to take a second look.

The 1968 season marked the end of an era in which baseball for decades had changed only incrementally. It was the year that Mickey Mantle took his last swing. Astroturf was soon to be installed in the new multi- purpose stadiums being built in Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Cincinnati. Before long, free agency would result in player salaries—and team payrolls— that exceeded the expectations of players, owners, and fans alike. With the expansion of the American and National Leagues to twelve teams in 1969, MLB, following the example of the NFL and NBA, doubled the number of races by dividing the NL and AL into an Eastern and a Western Division and scheduling a post-season playoff to determine the league champion. The New York Mets, the first world champions under the new system, made a storybook run that year, rising from ninth place the year before, surging in August and September to catch and then pull ahead of the Cubs, and then beating the heavily favored Orioles in the World Series in four consecutive games after dropping Game 1.

Increased run production, a new generation of high-profile managers, a new, young commissioner, the increased power of the players’ union, revamped league formats and the introduction of playoffs, new multi-purpose stadiums—all these coalesced to propel the national pastime beyond its lethargy of 1968, the most visible symptom of which was the overdominance of pitching, and it was this amalgamation that led baseball on the path to the current modern game.

PAUL HENSLER, a SABR member since 1979, lives in Connecticut. He is researching a book on the American League in the 1960s and 1970s.

Other Sources

The Baseball Encyclopedia. Ninth Edition. New York: Macmillan, 1993.

The Complete Baseball Record Book. St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1992.

Gillette, Gary, and Pete Palmer, eds. The ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia. New York: Sterling, 2007.

McLain, Denny, with Eli Zaret. I Told You I Wasn’t Perfect. Chicago: Triumph Books, 2007.

Notes

-

“Spitball Rule Is Revised Again, Eliminating Balk and Providing for Fines,” New York Times, 21 March 1968, 3.

-

Rex Lardner, “The Pitchers Are Ruining the Game,” New York Times, 16 June 1968, sect. 6, 12.

-

Lardner, 13.

-

Hubbard quoted in Lardner, 68.

-

Leonard Koppett, “Dodgers Will Alter Outfield Dimensions as Aid to Hitters,” New York Times, 14 November 1968, 58.

-

Koppett, 58.

-

Fay Vincent, “Shame on the Hall of Fame,” Manchester (Conn.) Journal Inquirer, 12 December 2007, 27.

-

George Vecsey, “Baseball Rules Committee Makes 3 Decisions to Produce More Hits and Runs,” New York Times, 4 December 1968, 57.