A Fox in White Sox

This article was written by Joseph Wancho

This article was published in The National Pastime: Heart of the Midwest (2023)

In the modern game, a team’s fortune or failure is often the burden of the general manager. The GM hires the field manager, signs or passes on available free agents, makes transactions with teams, and, with the farm director and his legion of scouts, oversees the amateur free agent draft.

Out of all that activity, it is the trades that many fans remember the longest. Every franchise in the major leagues can lay claim to moves where their GM hoodwinked the opposing front office, as well as those deals that have every fan asking the rhetorical question “What the hell were you thinking?”

In 1948, the White Sox finished in last place in the American League with a 51-101-2 record, 441/2 games behind pennant-winner Cleveland. It was the fifth straight losing season for the South Siders. Chicago vice president Chuck Comiskey named Frank Lane as the general manager of the Sox in October 1948, replacing Leslie O’Connor. Previously, Frank Lane served as president of the Triple-A American Association from 1946 to 1948.

Over the years there has been much scrutiny of Lane and the deals he made, but these naysayers did not deter him. “Don’t cry about a bad deal,” said Lane. “Walk away from it and go on to the next one. The worst thing a general manager can do after a bad deal is to stand pat.”1

It should be noted that while the White Sox never won a pennant during Lane’s reign, they were in much better shape when he left in 1955 than they were when he arrived. He doesn’t get the credit he deserves for building the foundation of the “Go-Go Sox” of the 1950s. The Sox broke through and won the American League pennant in 1959.2

Lane got right to work improving the team for the 1949 season. His first deal, on November 10, 1948, was acquiring pitcher Billy Pierce and $10,000 from Detroit in exchange for catcher Aaron Robinson. For the next 13 seasons, Pierce was a starting pitcher for the Sox, winning 20 games twice, and winning at least 14 nine times. As of 2023, Pierce ranks fourth all-time in wins for the Sox, with 186. He is also the team’s all-time leader in strikeouts with 1,796.

Less then a year later, Lane added another critical piece to the Sox. Like the deal for Pierce, he gave up very little while acquiring a cornerstone of Sox history. “When I was still president of the American Association, I stopped off one night in Lincoln, Nebraska and saw their ballclub,” said Lane. “And they had two little guys that I loved as soon as I saw them. A lefthanded pitcher and a second baseman with a huge chaw of tobacco in his left cheek. They were Bobby Shantz and Nellie Fox. ‘If I ever get to the big leagues, these are the two guys I’m going to get.’ Well, I never got Shantz, but I did get Fox.”3

Indeed, he did. On October 8, 1949, Connie Mack, the owner and manager of the A’s, dealt catcher Buddy Rosar to the Boston Red Sox for utility infielder Billy Hitchcock. With the A’s now in the market for a catcher, Lane was only too happy to help them. On October 19, Lane traded catcher Joe Tipton to the Philadelphia Athletics for Fox.

In his biography of Connie Mack, author Norman Macht wrote that White Sox vice-president Chuck Comiskey had initially asked for infielder Pete Suder as compensation for Tipton. Since Suder was a favorite of Connie Mack, Fox was offered instead. The Athletics did not foresee Fox rising above the status of a utility player.4 In hindsight, Mack rated the Tipton-Fox deal as the worst transaction he ever made, supplanting selling pitcher Herb Pennock to Boston in 1915.

Suder was blocking Fox’s path to a starting job at second base in Philadelphia. The Aliquippa, Pennsylvania, native was the A’s starting second sacker in 1947 and 1948. In 1949, Suder (right-handed batter) and Fox (left-handed) shared duties at the keystone, sometimes Fox playing second while Suder handled third. Suder showed a greater ability to provide the A’s offense, hitting 10 home runs, driving in 75 runs and batting .267. Fox’s line was less impressive: 0 home runs, 21 RBIs, and a .255 average. In the field, Suder played 100 more innings, committing 12 errors to Fox’s seven.

Stan Baumgartner of the Philadelphia Inquirer noted that Fox was five years younger than Tipton, and outhit the catcher, .255 to .204. But while Fox was a “singles hitter,” Tipton had “plenty of power” in his bat. He hit three home runs. Fox also drove in 21 runs compared to Tipton’s total of 19.5

One has to wonder what the A’s considered a power hitter. In 1941, Tipton’s first season in professional baseball, he stroked 13 round-trippers. That was the high-water mark in his career.

“We were short of capable infield reserves,” said Lane. “Especially, we needed a replacement for Cass Michaels. Fox has tremendous promise and fits in with our plan of rebuilding the Sox with youth.”6

It was a curious comment. Michaels batted .308 in 1949 and was selected to his first All-Star Game. But more importantly, at the time of the Fox-Tipton deal, Michaels was still on the Chisox roster. If there was one similarity shared by both Tipton and Michaels, it was that both players had their difficulties getting along with Chicago manager Jack Onslow. Although Lane and Onslow disagreed at times as GMs and managers will do, they were on the same page regarding Tipton and Michaels: Both players had to go. Michaels started the 1950 season at second base. Despite batting .312, he was traded to Washington on May 31 as part of a six-player swap. The deal opened the door for Fox to become the starting second baseman.

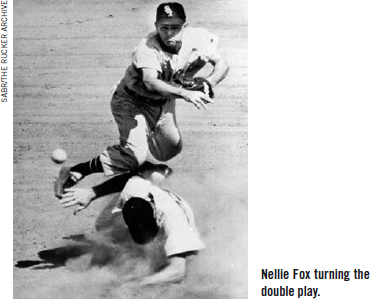

The new second-sacker of the Sox, however, was hardly a finished product. As Chicago worked out in spring training in Pasadena in 1951, it was apparent that Fox would need instruction with the bat, and his glove. “It was brutal the way Fox was pivoting (at second base),” said new Chisox manager Paul Richards. “I was surprised he didn’t get hurt making the pivot the way he was dragging his foot across the bag.”7 Richards brought in Joe Gordon to tutor Fox.8 Gordon had retired from the majors after the 1950 season and was beginning a new chapter in his life as a player-manager for the Sacramento Salons of the Pacific Coast League.

While Gordon worked on his glove and footwork, Chicago coach Doc Cramer tutored Fox on the finer points of hitting. This included Fox changing his bat from one with a thin handle to one with a thicker handle. Cramer also worked on reducing Fox’s habit of lunging at pitches.9

Like a sponge, Fox absorbed the extra tutelage. He batted .285 or better every season from 1951 to 1960. Within the decade, he led the American League in hits four different seasons. Fox had a steady eye at the plate. In his 19-year career, he only struck out 216 times in 9,232 at-bats.

In the field, he led AL second baseman in fielding average six times, and from 1952 to 1961 he led the league in putouts by a second baseman every year. Fox also led the league in assists in six seasons. He was selected as the American League’s Most Valuable Player in 1959. He was the recipient of the Gold Glove in 1957, 1959, and 1960.

As for Joe Tipton, he played seven seasons with four different teams, all in the AL. His career batting average was .236 with 29 home runs and 125 RBI. He also fielded his catching position at an average of .984.

Fox played 19 years in the big leagues. He compiled a lifetime batting average of .288 and fielded his second base position at a .984 clip. Fox was selected to the most All-Star Games in White Sox history with 15. He was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1997, 22 years after he passed away from cancer.

JOSEPH WANCHO lives in Brooklyn, Ohio. He has been a SABR member since 2005. Wancho has contributed to both the Games Project and the BioProject and is the author of the book “Hebrew Hammer: A Biography of Al Rosen, All Star Third Baseman,” published by McFarland. He is currently working on his second biography, on Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Lemon.

Notes

1. The Sporting News, June 15, 1960: 9.

2. Ironically, Lane helped the White Sox win the 1959 pennant from afar. While the GM of Cleveland, Lane traded Early Wynn and infielder-outfielder Al Smith to Chicago for Minnie Mihoso and Fred Hatfield in 1957.

3. Bob Vanderburg, Frantic Frank Lane: Baseball’s Ultimate Wheeler-Dealer (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2013), 14.

4. Norman Macht, Connie Mack: The Grand Old Man of Baseball (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2015), 446.

5. Stan Baumgartner, “A’s Get Tipton in Trade for Fox,” Philadelphia Inquirer October 19, 1949: 47.

6. “White Sox Trade Tipton for Fox,” Chicago Daily News, October 18, 1949: 29.

7. Robert W. Bigelow: SABR Biography Project: Nellie Fox. https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/Nellie-Fox. Accessed April 1, 2023.